"Wuthering Heights"

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: This review contains major spoilers for “Wuthering Heights”. Reader discretion is advised.

When Emerald Fennell released Promising Young Woman, I was chuffed to see what was the starting point of a hopefully promising career. The fact that Fennell is now three films in and her work is progressively getting weaker is disheartening: Promising Young Woman appeared to be a great debut, not the absolute peak of one’s career. It is premature to make such a declaration, sure, but after the decent risks found in Saltburn (a film that is mainly held back by Fennell’s propensity to try as many things as possible), and now a less-than-stellar “Wuthering Heights”, I feel like this is a director who is suffering from something akin to M. Night Shyamalan. Shyamalan was known for his incredible twists after The Sixth Sense and Unbreakable stunned audiences; he became subservient to the endings of his films more than the proper craft of entire screenplays, so much so that he churned out disaster after disaster all in hopes of astonishing viewers once more. It was a gimmick he could not shake off for the longest time. Fennell similarly wants to achieve that twist ending, but her drive is a little different but similarly debilitating: she cannot stop surrendering to stylistic abrasion. Her curious choices made Promising Young Woman come alive and feel fresh and unique. Her doubling-down in Saltburn let us with a few head-scratching decisions, but the bulk of the film was something we could not shake off (for better or for worse). With “Wuthering Heights”, Fennell goes so far with doing “stuff” just for the sake of it to the point that we are not watching a film. We are witnessing an endless parade of vibe checks, and each check performs worse than the last. Like Shyamalan, as rough as this sounds, I no longer feel comfortable in directors who lose sight as to what actual “direction” is.

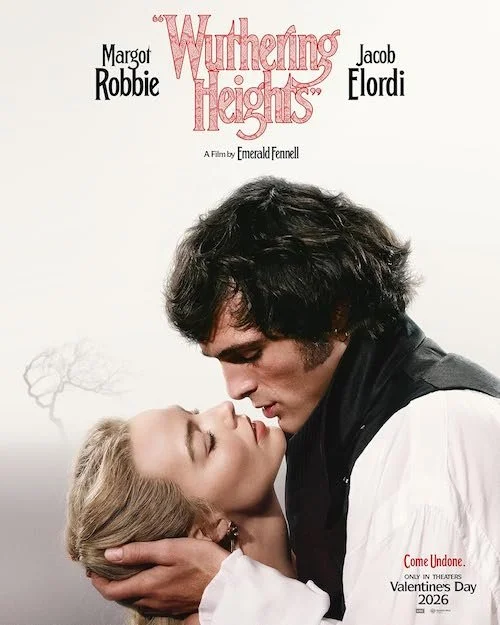

I can only hope that I can surmise what Fennell was wanting to accomplish with “Wuthering Heights”: an adaptation of Emily Brontë’s iconic novel that is so loose that — like an oversized pair of pants — it can no longer even stay up on the body it is intended to suit. Brontë’s novel has been bastardized, misunderstood, and misrepresented by poor media literacy and romanticism for decades. What is meant to be a Victorian gothic look at trauma and abusive love. It is frequently depicted as something romantically passionate and endearing instead again and again (even the best film versions are at least slightly guilty of this, in the same way that a number of the best Frankenstein-related films misrepresent the monster from the original novel). Fennell seemingly triples down on these expectations to the point of heightened sexuality and eroticism, starting with the opening sequence of a man being executed who is sporting an erection while he dies (I guess you can call this a hanged, hung guy). From there, Fennell brings us the iconic literary characters of Cathy (Margot Robbie) and Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi), starting from their childhood connection (each character is played by Charlotte Mellington and Adolesence’s Owen Cooper, respectively). Fennell does try to get into the minds of these cursed lovers, but the majority of her focus is on their repressed sexuality, desires, and self-loathing more than anything that would allow them to actually feel like real people.

Emerald Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights” plays the anachronism card a little too frequently to the point of feeling flimsy, not confident.

Regardless of how much Fennell tries to set up the rest of the film — from the separate relationships Cathy and Heathcliff have, to her depiction of the United Kingdom in the eighteenth century — so much of this adaptation is contingent with trying to set up this permanence between its two lead characters. That would mean something if Fennell at least stuck to the most integral part of Brontë’s original story: the “ghost” side of things (where the deceased Cathy haunts Heathcliff as per his wishes). However, we don’t even get that far. The film cuts after Heathcliff’s longing for his now-deceased lover. I do not have a problem with storytellers straying away from their source materials, but none of Fennell’s choices make sense with this changed ending: if she was forever setting up the film for Heathcliff to be haunted both by what has transpired and what is to come, why would she take away the moment that actually condemns him? I suppose the implication is that Heathcliff’s regret will curse him enough, but what good is that when such a choice renders the film feeling unfinished? Is that the twist ending? To get rid of the iconic conclusion many have come to expect? To not even have an ending? To be fair, Brontë’s novel has more after these events, and I suppose this is where most adaptations have agreed to finish things, but Fennell’s version chooses to conclude thins even earlier than your average adaptation. Should you want a summary as to what should happen after Fennell’s version concludes, a fast and tremendous CliffsNotes version is Kate Bush’s iconic “Wuthering Heights” song.

While “Wuthering Heights” is a borderline mess in a narrative sense, I do like how Fennell has pushed herself furthermore as a visual storyteller with a film that strengthens her aesthetic eye and affinity for taking gambles; while her plot choices are worsening, she is at least remaining bold artistically. Yes, this includes the many contextually-inaccurate choices, including those frequently-discussed costumes — and who could forget the inclusion of Charli XCX songs that make key sequences feel like elaborate music videos in the middle of a not-so-costume drama? However, being anachronistic just for the sake of it can also fall flat. When Sofia Coppola kicks off Marie Antoinette with post punk icons Gang of Four’s “Natural’s Not in It,” I get the sense that this is a film that is vowing not to play by the rules just like its central figure; the remainder of the soundtrack is consistently a new wave feast for the ears that manages to maintain Coppola’s unique vision as to how to change the historical biopic. Fennell seems transfixed by making this BDSM-yearning fantasy that doesn’t comment on Brontë’s text and its cultural impact as much as it proves to be a catalyst for everything wrong with the zeitgeist of fan culture. Sure, strong performances by Robbie, Elordi, and Hong Chau can help add some truth to an adaptation that feels quite void of substance, and the film’s hypnagogic artistry is at least marginally hypnotic, but these all pertain to what the experience of watching “Wuthering Heights” is like. There is nothing to take away with from here. There is no ghostly Cathy banging on our window for the rest of our lives. We get the idea of a dynamic, powerful depiction of what an adaptation can be, but said adaptation does not exist here. Unlike most adaptations that can be too focused on the ghostly elements of Brontë’s story, Emerald Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights” is soulless from the jump.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.