The Best 100 Films of the 1920's

WRITTEN BY ANDREAS BABIOLAKIS

Well, we have reached the final decade list of my experiment. We will have a few additional “Best 100” lists (including the best documentaries, short films, music videos, and one hundred important early films that came before the year 1920), but this “Best 100 Films of the 1920’s” is as far back as I’m going with selecting the greatest feature films of an entire decade. There are a few reasons for this. Firstly, the 1920’s, while excellent, was a signal that ranking works from here on out is only going to become even more shallow. Secondly, we’re at a point where the majority of films are problematic in a multitude of ways, and I fear that trying to label some of the earlier films as “better” than others (especially when there are so many aspects of early film history that I’m not exactly thrilled about) just feels wrong. Besides, the ‘20s was when film was becoming what we know it as now. There are definitely feature works that came before this decade, but this was the first chunk of time when there are enough excellent feature films to make a list like this.

So, let’s take this opportunity to soak in where we’re at right now. At this list’s oldest possible entires, some of the films here are one hundred years old. One. Hundred. Years. Old. That’s mind boggling. Thanks to the internet, film preservation, and the discoveries of lost films happening at random times, we have access to these works that depicted a world one whole century ago. That’s another key factor: these are only the best one hundred films of the 1920’s that we know about. There are countless lost films that we can only hope to find one day, if they even exist in any capacity (there’s a big chance they simply don’t). Will we be able to update this list one day when 4 Devils is finally dug up? What about our ability to reevaluate any of the films that are missing portions? We slowly found out why not many outlets have tried to make a list like this for the 1920’s: you’re sifting through a small pool of what actually once was, and any effort won’t be the ultimate representation that the time period deserves.

Nonetheless, I found the experience very fulfilling (although watching nothing but silent pictures [with the occasional talkie] was certainly interesting). The 1920’s was home to a club of hungry storytellers trying everything they can to seize this rising medium, before it was fully figured out. There are a few iconic faces and names, who were even big for their time (like Mary Pickford or Buster Keaton, amongst many others), but this is still a sandbox where so many different ideas were tossed into theatres to see what would stick. One hundred (or so) years later, we’ve had more than enough time to see what time has dictated as the finest pictures, as per the evolution of cinema from this point on. Out of all of the films I could actually watch, I feel like this is a fine selection of inspirational pictures in the roaring ‘20s: both the works and their respective era chased for the future of innovation, art and culture. Here are the best one hundred films of the 1920’s.

Disclaimer: Documentaries and shorts are to be featured on upcoming lists, and will not be included here.

Be sure to check out my other Best 100 lists of every decade here.

100. Seven Chances

My, how the romantic comedy has changed. There might not be any better indication of this than the appalling 1999 dud The Bachelor, which completely misunderstands the fun of Buster Keaton’s Seven Chances; antics become pet peeves, and natural gags become forced pleas for laughs. Going back to the film that matters, Seven Chances is one of many Keaton masterworks that ended up on this list, and it remains the lowest of those films featured only because it felt less inventive than his greatest visions. Seven Chances is still a riot, and it certainly features some of Keaton’s silliest reactions (all through that iconic deadpan gaze, nonetheless), particularly to all of the scenarios he gets wrapped up in.

99. The Joyless Street

During Germany’s economic difficulties, German expressionism rose from the ashes of abandoned industries and lives. However, not everyone was feeling the need to express themselves in gothic imagery, metaphorical jabs and thick coats of makeup. So, there was the countermovement called New Objectivity, and G. W. Pabst’s The Joyless Street was one of the most direct examples that spoke specifically to the German citizens who didn’t want to be pandered to by art. Led by Greta Garbo before she really dominated on a global scale, Pabst’s unforgiving film pits similar lives together and sees fate dish them different hands. The Joyless Street is a highly relatable work for its time, albeit an extremely harsh film at times.

98. The House on Trubnaya

A few years after the New Economic Policy of the Soviet Union was put into place, director Boris Barnet decided to have a laugh about it with The House on Trubnaya. Featuring the titular house, which symbolically is condensed and with many inhabitants, Trubnaya is a fantastic silly metaphor for a mightily controlling government, with every citizen under the same roof (literally, in this case). This makes for visual comedy, as well as clever choreography, with Barnet cramming in as much as he can in an hour and a half. He succeeded, with The House on Trubnaya taking full advantage of the silent era’s confinements and turning them into symbolic gold.

97. Lucky Star

As if inspired by the metaphorical ways of German expressionism, Frank Borzage’s Lucky Star took a literal crisis (an injury caused by combat) and turned it into symbolism (with the kind of climax that is more cinematic than likely). That’s the magic of film, though; tell a good enough story, and audiences can suspend disbelief, even if this is all in the names of convenience and message. Lucky Star is a love triangle that is affected by World War I, particularly with both men who serve, and the sole woman (played by a superstar Janet Gaynor) who waits for them. Driven by the emotions caused in romantic rifts, Lucky Star is more soul than real, and that’s perfectly fine.

96. The Wedding March

Erich von Stroheim was synonymous with the idea of passion projects (more on that later on in this list), so the very nature of The Wedding March’s existence is kind of funny in a peculiar way. Here you have a romantic film that was too ambitious for Paramount Pictures, so it was sliced into two different films; the second portion became The Honeymoon. The latter is now a lost film, leaving only part of Stroheim’s vision intact (this became a bit of a running theme for him, unfortunately). Still, on its own, The Wedding March (which stars Stroheim himself; remember, passion project) is a moving tale of a dilemma caused by the kinds of decisions one has to make in a world driven by fortune (a common theme for Stroheim).

95. The Docks of New York

Much about The Docks of New York — the second last silent film Josef von Sternberg made — is about timing, whether this involves serendipity or strategy. Knowing the pulse of his films through and through, Sternberg takes complete advantage of the pacing of a film (even in the choppier ‘20s) to create tensions, respects, and connections between people and situations, all within his usual cinematic murkiness. With opportunity comes choice, and that’s a series of gambits Sternberg presents us with the convenience of time stalled, whether it’s the use of intertitles to pause a cinematic moment, or a breath to clear one’s thoughts.

94. La Souriante Madame Beudet

One of the auteurs to take complete control over the silent film formula was Germaine Dulac, whose blistering works helped to challenge the mind, soul and heart. La Souriante Madame Beudet is a test of wills, presented by an unhappy couple and their pistol. The fickleness of cinema is that we are forced to have the perspective we’re given. Dulac knew this, and let that be the primary gimmick of this feature. Dramatic irony becomes our own blindspot, as La Souriante Madame Beudet swoops in with the unexpected (twofold), and leaves us with a much more meaningful message than before. Like a modern day short stretched out in a 20’s featurette form, Dulac’s fable is concise yet powerful.

93. The Student of Prague

It didn’t take cinema long before the same old stories were repeated (for anyone complaining that film doesn’t have imagination anymore). The Student of Prague is not the only feature based on the story of Faust (hell, Faust itself pops up later on on this list), and it isn’t even the first take on this literal version of it (the 1913 The Student of Prague is less interesting in almost every way). Granted, Henrik Galeen might have been a little late to the German expressionist party (only to go head-to-head with F. W. Murnau the same year), but this mid-career depiction of one’s quest for ultimate success and happiness at their own detriment was still nonetheless fitting in ‘20s Germany, and he seized the moment with arguably his finest work (against all odds).

92. The Last Laugh

F. W. Murnau loved prioritizing the art side of silent cinema over narrative, and this included the literary ways that silent films were told. When he wasn’t dressing up intertitles, he was trying to do away with them for the most part. Enter The Last Laugh: one of the era’s attempts at being purely visual (with great success in this case). To get the best emotional results, one couldn’t have cast many actors that were better than Emil Jannings, who epitomizes embarrassment and devastation within the clutches of poverty, particularly after falling from grace. Murnau excelled at poetry, and this applied to his depictions of real life scenarios as well.

91. Applause

The first talkies were able to experiment with what they wanted to say (and I mean actually verbally say, for once). Well, Rouben Mamoulian’s Applause didn’t take this opportunity lightly, depicting a harrowing take on misogyny in the arts and in society. He and his crew made sure of this, too, by completely utilizing the best sound technology they could muster at the time, and coming away with some of the clearest, most direct results for 1929. All of this is meant to provide voices for mistreated women, who are caught in the cycle of being in abusive industries because they have to get by and are forced in these positions. Applause is thus cyclical, and also definitive (but not without bittersweet ambiguity).

90. Steamboat Bill, Jr.

This was Buster Keaton’s last hurrah before the big time with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, when he released The Cameraman, and then singlehandedly be destroyed by the studio system overnight afterwards. Our final look at a comedian visionary in complete control is Steamboat Bill, Jr., where his usual hijinks could be refined and made better than ever. One instance where this plan worked is the legendary gag where an entire house’s wall falls over and narrowly misses Keaton, who is standing right where the empty window hole lands (he did, however, get swiped by the side of said window, and actually get hurt). Even though he had his usual stone visage, this is where you can tell Keaton was genuinely happy for the last time.

89. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Even in 1920, John S. Robertson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is already the fifth iteration of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Victorian horror tale. On Robertson’s side is John Barrymore as both of the title characters, and he brought a certain spookiness to the role that perfectly matches the unnerving makeup work and dark imagery (which only ages so creepily one hundred years later). Robertson’s version, like many of this time period, retains mostly the horror side of the story without trying to play itself off as a straight forward film at any point; the main difference is the 1920 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde still manages to balance all of the storytelling elements to be compelling enough to stand out amongst the rest (with the unnerving style on its side).

88. Isn’t Life Wonderful

Out of the countless films D. W. Griffith made, it’s mainly the epics — and problematic natures — that have captured attentions one hundred years later. However, it’s when he’s operating at his most stripped down that he is sometimes at his absolute peak. Teaming up with Carol Dempster and Neil Hamilton as the forefront couple in Isn’t Life Wonderful, Griffith obviously was opting for warmth in this tragic depiction of people affected by the aftermath of a World War. Even with all of the atrocious elements of Griffith’s infamous filmography, there is the occasional moment of beauty, when he aimed to connect with people on an emotional level.

87. Destiny

Ingmar Bergman’s human depiction of death in The Seventh Seal has been parodied and homaged for decades, but even his vision was only paying tribute to what Fritz Lang created in Destiny. When silent cinema was getting aesthetically inventive, them came Lang — who is arguably the greatest innovator of the era — with his many ideas, including this gloomy series of fables on love lasting longer than life itself. The only overarching theme is that death (like us) is an observer of these various lives, as if we escape our own realities for a minute (or we experience lifelessness temporarily). Lang would go on to make much longer serials and multipart films, but Destiny was his exercise in conciseness.

86. Zvenigora

The first film in Alexander Dovzhenko’s Ukraine Trilogy is Zvenigora, which contrasts nicely with Arsenal’s depictions of war and Earth’s commentary on prosperity. In Zvenigora, Dovzhenko explores self worth, particularly in a very fragile time in the Soviet Union. It’s the most spiritual film in the trilogy, turning the stripped down tale of adventure into an epiphanic experience matched by visual splendour. Unfortunately, Zvenigora has been cast aside by the legacies of the other Ukraine Trilogy entries, because there is a certain beauty in the former film that paved the way for the latter two, as if it were a necessary stepping stone for Dovzhenko (and Soviet cinema).

85. The Navigator

Buster Keaton often made films that provoked discussions about class systems, either by playing the part of the poor or of the rich. In The Navigator, he mimics the fortunate. These focuses also affect the general tone of the stunts and gags Keaton weathered; an unfortunate person is experiencing an uphill battle, for instance. In The Navigator, it’s all about comeuppance, and the hope that the spoiled elite might change their ways amidst all of the stupidities (it’s still funny to watch the buffoonery in the meantime). To top it all off, The Navigator boasts some of the best effects of any Keaton feature, just to flex his expertise as a cinematic artist.

84. Foolish Wives

We all know about where Erich von Stroheim went with his short-yet-prestigious career, particularly with his epics and ambitions. However, where it all started is arguably with the breakthrough Foolish Wives, which was originally meant to be around ten hours long (which honestly is no surprise, considering who we’re dealing with). Still, there’s Stroheim acting in a leading role (the considerably shady and disturbing Count Wladislaw), with the highest budget in Hollywood history (at that point): he was clearly never going to shy away from aiming for the top. This was only the start of Erich von Stroheim’s legacy as the game changer for American silent epics; if only studios didn’t keep pushing against his visions.

83. The Kid Brother

Making a list like this helps shed light on Harold Lloyd, who has been limited to a single image of Safety Last! (which is still a genius comedy, and will be featured later, as well as other Lloyd classics). As usual, Harold Lloyd (here as Harold Hickory) has something to prove in The Kid Brother: it’s his coming-of-age film of sorts. Instead of competing against society, romantic interests and other elements, Lloyd faces his family, of whom he cannot compare with. So, we celebrate his many attempts at trying to mature and overcome his cowardice; his triumphs are just as funny as his failures.

82. Cœur fidèle

Jean Epstein vowed to channel some of the darker elements of the human experience in his works, paving the way heavily for cynical French impressionists that would follow in his footsteps. When he conveys emotions, they’re usually hyperbolic, in a way that the visual storytelling greatly surpasses the limitations of not having sound. Cœur fidèle fulfils this mantra by placing humanly dramas in extreme locations and under much scrutiny, as if the world was going to crash down on the three players at any given moment. We await for any moment to strike in the film, knowing that the worst can happen whenever and to whomever; the uncertainty of what exactly will play out is just Jean Epstein’s love of the uncertain.

81. Way Down East

If there was a start of the silent era that could match the limitless ambitions of D. W. Griffith, it’s easily Lillian Gish, who nearly died while shooting Way Down East; she suffered frostbite and permanently lost feeling in parts of her hand, all due to her own dedication (Griffith got frostbitten during production as well). All of this was meant to symbolize the efforts one makes to get out of a suffocating position in their life, which Gish embodies throughout the tumultuous marriage at the centre of the film. It all leads to the iconic ice float sequence, which remains an untouchable moment for filmmaking and cinematic acting today.

80. Body and Soul

One of the greatest triumphs in Oscar Micheaux’s career is the debut acting gig of Paul Robeson in Body and Soul: an opportunity for both visionaries to truly shine. Depicting a conflict with religious morality (particularly with Robeson putting in double time playing twin brothers of drastically different natures), Body and Soul is a series of parallels between the physicality of living as a breathing creation, and the spiritual cleansing of the damned. A tale that could match most of the working class American tales that other directors came out with at the time, Micheaux helped break ground as a black filmmaker that could tell tales of corruption and greed in the name of the American dream just as well as the Griffiths and Stroheims of the world.

79. Street Angel

Two of the films that Janet Gaynor won an Academy Award for were both directed by Frank Borzage (this was the first and only time that performers won single awards for many films, and the Academy did away with this regulation after the very first ceremony). The second of these two is the take of challenged karma known as Street Angel, and Gaynor is exactly the lead that we should be right behind for this kind of a picture. If anything, Street Angel is a puzzling picture that places us at a crossroads at almost every possible instance, seeing what Gaynor (as lead character Angela) will do to get by (or escape the outcomes of her trying to get by in previous instances). It’s a battle between luck, fate, and survival.

78. Sparrows

Who do you cast if you have a film about a group of orphans being led to safety by the eldest person in the bunch? Why, mega legend Mary Pickford, of course! To be fair, Pickford produced Sparrows anyway, so chances are she was going to be the star of this picture, so it’s only natural that she plays the maternal figure for both the feature and the narrative within. Released around the end of her silent era, Sparrows is yet another hurrah for one of the greatest names in silent cinema, placing her in a heroic position full of numerous fearful moments; like she did with film artists’ integrities via United Artists, Mary Pickford saved the day (as per usual) here as well.

77. Blackmail

The first talkie Alfred Hitchcock ever made, Blackmail was the first of many evolutions in the iconic director’s canon. So, how did he utilize sound for the first time? By turning the words of others into the biggest weapon of all. Alice is cursed by manipulation after she kills an abuser in self defence (a close up, obstructed murder in typical Hitchcockian fashion), and the malicious intentions of the discoverers of this crime. Basically, the moral of the story is that giving someone like Hitchcock any additional cinematic element means he’s going to exploit it as thoroughly as possible (which was always a good thing).

76. Bed and Sofa

Rarely does the director credit of a film equate to the main objective of what a leading character is searching for: A. Room. Jokes aside, Abram Room’s satirical Bed and Sofa is right in the middle of what Soviet cinema was looking like around this point (neither fully light hearted, or entirely cynical). A visitor finds his way over to a friends home, to crash with him and his wife, all with a struggling Soviet Union as a mightily appropriate backdrop. Isolated from the world, the connections between all parties involved here make for an intriguing study, especially because of how richly written every character is (especially Liuda, in a time when women characters usually weren’t well crafted, carefully designed or developed at all).

75. 3 Bad Men

Towards the end of John Ford’s silent era (which houses countless works) was the best feature of this chapter in his life: 3 Bad Men. This wonderful western places a trio of outlaws in a position where they can cleanse their souls as the saviours of an abandoned girl. Ultimately, this turns into a test, with different questions and answers for each of the bandits, and a whole basket full of choices for audiences to flip through. Naturally, Ford would toy with the ideas of one’s conscience coming into question time and time again (particularly set to the backdrop of the unforgiving west), but 3 Bad Men is a thrilling precursor to all of his future opuses.

74. The Red Kimono

Dorothy Davenport was always a director who intended on going the distance, and The Red Kimono is as much an artifactual statement on how an industry pushes against it artists as it is a film. Having co-directed the film without credit (Walter Lang received the full title) and produced the film under a pseudonym, Davenport’s depictions of Dorothy Arzner’s adapted screenplay depict a lone woman (Gabrielle) facing a patronizing world alone, either through struggling or through being manipulated. It’s quite a challenge to watch Gabrielle feel comfort in a position that’s using her, but it’s the kind of feminist game changing storytelling that filmmakers like Davenport and Arzner vowed to share.

73. The End of St. Petersburg

The backdrop of the unnamed protagonist’s woes in The End of St. Petersburg is interesting, because it’s as if the setting could empathize with one of its inhabitants. In an area brought to the brink of ruination before Red October, the lead character fights so hard to get by, only to continuously be cast aside or penalized (he tries to follow order and faces guilt, or he does what’s right and gets punished). We’re watching the birthing of someone who can no longer take society’s wicked ways anymore, and The End of St. Petersburg is a precursor to a revolution without featuring said revolution; however, sometimes it’s the setting up of an event that succeeds enough on its own as a great story.

72. Speedy

Okay, so the lead character’s nickname is Speedy, but we all know this is Harold Lloyd playing a Harold of some sort once again. That doesn’t mean that Speedy is any less of a standout picture in the comedian’s oeuvre. Embodying all of New York City in one single person (who manages to partake in many of the Big Apple’s finest past times and passions), Speedy and his shenanigans feel like a time capsule nearly one hundred years later. Naturally, not a hell of a lot has changed in New York: transit is crowded, taxis rule the roads, baseball is the greatest event, and Coney Island is the destination afternoon getaway.

71. The Love of Jeanne Ney

Russian cinema was so gigantic in the ‘20s, even outsider directors were trying to capture its stories. G. W. Pabst — who was already combining German expressionism with the ways of American cinema — tried to channel Soviet cinema with The Love of Jeanne Ney, down to basing this tale right in the middle of a civil war. With a series of characters operating by their own motives (amidst a crisis), The Love of Jeanne Ney allows us to only examine one such person, as devotion to them in such a calamity is enough. Jeanne Ney herself faces many oppositions, and actress Édith Jéhanne makes her such a dynamic character to follow; it’s unfortunate that she was barely seen or heard from again.

70. A Woman of Paris

Of all of the Charlie Chaplin directed features, there’s one film that stands out enough to warrant being brought up in such a way: A Woman of Paris. If you didn’t read that the comedic legend produced, directed, and wrote the film, and if the film didn’t remind viewers that this was a serious film despite who made it, we guarantee you’d have no idea that it was a Chaplin creation at all. Even with this in mind, Chaplin’s token heart shines through the picture, as a tug-of-war between life’s unfair options for the titular character. Even though we didn’t see Chaplin stay behind the camera more often, this unusual entry in his filmography was more than enough proof that he excelled at filmmaking in this way as well.

69. The Cave of the Silken Web

Countless amounts of films could have ended up on this list, but they have been deemed lost, either entirely or with enough missing to be too incomplete. Then, the miracles of discovery and preservation take place, and rescue an additional film to help us further understand the cinema of yesterday. The Cave of the Silken Web has only existed for the last seven years, having been all but a watchable film for nearly ninety years. Dan Duyu’s extraordinary depiction of Journey to the West takes the mystical, scary, and peculiar sides of fantasy and places us right in the middle of these jaw dropping images of the silent era. I can only imagine how many other lost masterpieces like The Cave of the Silken Web will turn up over time (I can only hope).

68. The Love Parade

A major transition in the filmography of Ernst Lubitsch is his first talkie The Love Parade. Here was an opportunity for the visual comedy of the satirical icon to slowly be translated into audible jokes. So, Lubitsch went for gold by making his first sound picture one that was music based, with cabaret singer Maurice Chevalier right at the front of the picture. Toying with the idea of living under new societal conditions, Lubitsch makes his usual jab at the distances between different classes, and the obstacles placed at the feet of those that find themselves in an unfamiliar bracket (which can be turned into songs, of course).

67. El Dorado

At the start of the roaring ‘20s, it felt clear as to who was winning the battle of cinematic innovation between America and France (the two earliest nations to create film as we know it; from the Lumière brothers to Edison, and et cetera). Hollywood was powerful, and American storytelling was reaching new places at rapid paces. However, France was always going to be just as important to cinema (I’d argue it’s more important, actually), and Marcel L’Herbier’s El Dorado was a breath of fresh air that proved it. Driven by intriguing aesthetics and a focus on technical capability, El Dorado is a push that not only showed that France was still in the discussion, but that there was a lot left to discover from their greatest artistic minds.

66. Diary of a Lost Girl

Margarete Böhme was an important feminist writer in the early 20th century, whose work was bound to cross into cinema. In the late ‘20s, there was still a massive case of bigotry, so most of the men that would try to take on these themes would likely have misunderstood how to handle them. Luckily, G. W. Pabst was considerably sensitive, so his adaptation of Diary of a Lost Girl places emphasis in all of the right places: by showcasing the misogynist gaze of society that can peer through many of civilization’s open crevices. It was another partnership with Louise Brooks, who embodied all of the film’s themes with exemplary fashion.

65. Variety

Ewald Andre Dupont’s finest film is a balancing act that, appropriately, takes place within the world of the greatest show on earth: the circus. Variety features entertainers and their hidden intentions, as well as the overbearing cloud of envy that rests over the heads of the players for the entire film. The visual nature matches the crooked minds of the leads, particularly Emil Jannings as the “Boss”. As if we ourselves are wrapped up in an act, Variety rolls on and on and gets more and more deranged, making us feel like we’re going mad along with the picture. It’s a gradual descent into a Weimar nightmare, told with a lens warped enough to make each picture sit in our deepest psyche for the rest of our lives.

64. L’invitation au Voyage

Before she changed surreal art for good, Germaine Dulac was still ahead of all of cinema with her interpretive storytelling, which would predate poetic realism, French New Wave, and other artistic filmic movements in France. In her featurette L’invitation au voyage, Dulac gives us just enough time to deliver an entire possible lifetime ahead of a lonely, disillusioned wife that aspired for more. Clearly wanting to break out of society's conventions, Dulac paints a picture of a woman that was fully aware of the constraints of a male-dominated medium, and Dulac allows her to live freely for a little while. Sure, Dulac would make some of the greatest experimental works, but her more literal escapes from reality are just as gorgeous.

63. The Phantom of the Opera

The greatest version of The Phantom of the Opera, all things considered, is Rupert Julian’s silent classic version. First off, all you need are two words: Lon Chaney. The man of a million faces as the titular “Phantom” is absolutely terrifying, but also sympathetic enough that you understand why he reacts the ways that he does (even if this is easily the scariest rendition of the character). The film’s specific editing style also makes for some major surprises that can’t be matched by an audio track (even any accompaniment I’ve heard can’t compete with the visual language, which is honestly fine on its own). It might not be as emotional or romanticized as other versions, but the 1925 Phantom reigns supreme.

62. October (Ten Days that Shook the World)

Not the sole film on this list about Red October (see The End of St. Petersburg), October: Ten Days That Shook the World wasn’t exactly covering new ground. However, the film was commissioned by the Soviet government for two of their finest directors to make: Grigori Aleksandrov and Sergei Eisenstein. Meant to be a tribute for the ten year anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution, October is a cinematic exercise of juxtapositions, thematic contrasts, and triumph through visual spectacle. Having both revolutionary filmmakers work on this honorary statement is exactly the kind of technical splendour you would imagine, and it remains one of the great collaborations of early Soviet cinema.

61. Linda

Dorothy Davenport’s interpretation of Maxine Alton’s Linda screenplay is a fascinating take on societal conventions, particularly the shoehorning of one into life long commitments they might not agree with. The titular Linda falls in love with someone who is not her husband, which is a standard love triangle type of story; Linda, however, is not typical. When the film begins to toss its curveballs towards the audience, it becomes a hypnotic take on devotions, all while tables keep turning and placing each character in different mindsets at a regular pace. Love can arise in the weirdest ways, during the least expects moments and from discreet places in one's heart.

60. Lady Windermere's Fan

Ernst Lubitsch’s take on Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan is a fluid transformation that takes the late 19th century play and turns it into something tangible for ‘20s audiences. Now, we have a piece on connections and structure in the roaring ‘20s; particularly the plot of misunderstanding that creates a rippling effect of calamity feels like a reminder to appreciate when things are good, as they won’t always be. Maybe it’s because Lubitsch is a warmer filmmaker that Lady Windermere’s Fan is a bit less savage with how it deals with guilt and sorriness; the film is still impossible to pry one’s eyes away from regardless.

59. Our Hospitality

Our Hospitality starts off with a threat: the capability of death at the hands of a family based rivalry. So, Buster Keaton being planted in the middle of a similarly brewing scenario can only mean good things, right? The draw of Keaton’s deadpan face and stiff demeanour is that it will forever stick out like a sore thumb, no matter what the situation is. In Our Hospitality, he almost feels like a ticking time bomb, if not like a blindfolded character wandering across a minefield. You know the risks, and yet he is still stuck in this impending doom, as if you cannot slow down the inevitable. Still, it’s a Keaton film so it’ll never get too dark, right? Like Keaton’s stunts, Our Hospitality is a hilarious flirt with danger.

58. Sadie Thompson

We hear about the woes of a silent star’s fall from grace from the mouth of the delusional Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard: the revival of Gloria Swanson’s career. Rewinding back to the silent era will show us what this star’s heyday was like, and you’ll get a film like Sadie Thompson while journeying back. Swanson dominates the entire screen, with or without sound, and delivers one of the silent era’s great performances as sex worker Sadie Thompson herself. Unfortunately, the last portion of the only discovered copy of the film is deteriorated beyond repair, but we are still fortunate enough to have all of the pieces visible and understandable enough to complete this ‘20s gem.

57. The Penalty

Wallace Morsley’s The Penalty is the ultimate ‘20s film about revenge: a patient turns to crime, seeking vengeance on the doctor that accidentally amputated his legs. Furthermore, he plans to go further; his devious mind is now leading him towards lusting for power, by becoming the dominant criminal genius of San Francisco. Lon Chaney was known as the man with a million faces, but his leading role here is evidence that he was fully committed in every way. He is frightening (as usual) when he is carrying out his plans, but possibly even more scary when neutral. This is a man that is changed by hate, but The Penalty goes through narrative lengths to clear up his mind fogged up by devastation.

56. Within Our Gates

It’s not known for certain if Within Our Gates is the very first feature film by an African American filmmaker, but it is the oldest film to be rediscovered (Oscar Micheaux’s The Homesteader precedes this film by a year, for instance). One hundred years later, Micheaux’s touching picture contains social awareness: characters that depict their racist surroundings, and their best efforts to continue living, or try to bring change in their own ways. Micheaux didn’t want to sugarcoat this story — despite the moving moments — and places painfully tragic moments that stem from real hate crimes; these are the lives taken away by the hateful. Within Our Gates is the anti Birth of a Nation, and, frankly, it’s a better film through and through.

55. Mother

Vsevolod Pudovkin’s Mother pits the maternal title figure against the two male loves in her life: her son who is taking part in a strike, and her husband who is heavily against his child’s viewpoints (these were different Soviet ideologies bashing heads). Mother sprints ahead and becomes a revolution-favouring picture, like many Soviet productions at the time; the key hint is the title of the film, despite leading character Pelageya’s dual identities. Like these similar films, Mother does not shy away from destruction, and is willing to go as far as it can to fulfill its metaphors in complete fashion. It’s a gut wrenching result, but what an extraordinary picture.

54. The Unknown

Before Tod Browning would push boundaries with Dracula and Freaks, and Joan Crawford would dominate the big screen for decades to come, they both were attached to The Unknown: a freaky circus picture that’s predominately led by silent legend Lon Chaney. Chaney is a fugitive who has taken on a life of performing as an armless knife thrower to evade the crimes of his past, but his tendencies begin to creep back into his psyche. Even in a brisk fifty minutes, The Unknown gets eerie and unsettling enough to stick with you forever, especially the horse drawn climax. Chaney could always captivate, Crawford was meant to act for good, and Browning was born to disturb audiences in all capacities.

53. The House of Mystery

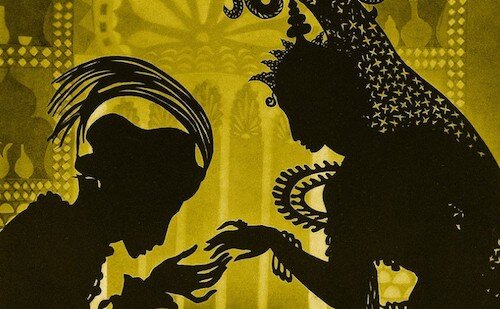

Alexandre Volkoff’s six-and-a-half-hour long silent serial The House of Mystery is ambitious through and through. Featuring brief silhouette sequences outstanding enough to remain iconic, there is a certain amount of beauty in this poetic epic. However, greed and corruption are the names of the game, and The House of Mystery is a series of events all in the name of manipulation and perseverance. As lovely as those silhouettes are, Volkoff’s visions are always jaw dropping; my personal favourite might be that “human bridge”, in all honesty. Nearly seven hours or not, The House of Mystery is a glorious fable that is well worth the undertaking.

52. From Morn to Midnight

The story in From Morn to Midnight is rather conventional ‘20s fare: the pursuit of success, at all costs. However, the main attraction of Karlheinz Martin’s forgotten gem is the insane lengths it goes through to hyper extend the capabilities of German expressionism. If The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a nightmare exemplified by film, then From Morn to Midnight is the craziest of hallucinations. The four sides of the screen become a frame for bizarre artworks that border on the lines of abstract (they may as well be if there weren’t living humans caught within these four walls to get our perspectives straight). Split into a five act structure, From Morn to Midnight is like a deranged opera made for the silent, visually inclined era.

51. The Lighthouse Keepers

2019’s The Lighthouse felt like an anomaly of an homage: a depiction of Golden Age horror pictures, frame rates and aspect ratios and all. However, there seems to be at least a noticeable connection with Jean Grémillon’s The Lighthouse Keepers (which doesn’t get as insane, let’s be honest). The lighthouse also acts as a claustrophobia-inducing chamber in this film, and there is enough madness to really get to you (all of this is sparked by a wild dog, and not the curse of a murdered seagull). Of course, it goes without saying that there are silent films of the ‘20s that have suffered being off the radar of many (look at how many are lost, and consider how many we don’t even know about), but The Lighthouse Keepers is still an underrated silent picture that can experience some new life in the internet age.

50. Underworld

Josef von Sternberg was always meant to shake up Hollywood, if his ‘30s tenure was any indication. However, he still had to make his way over there to secure his spot in the ever-evolving world of glitz and lights. So, he made Underworld: an American crime picture that launched Sternberg into the Hollywood stratosphere. Oddly enough, he wanted to find common ground in a foreign industry, but ended up changing it upon entry, by establishing a thirst for gangster pictures that would only spill over into the massive pre-Code boom of the genre in the ‘30s. As for Sternberg, he would continue making coveted silent films, and bring massive stars from overseas to Hollywood for the sound era of the ‘30s (and dominate that too).

49. The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog

Alfred Hitchcock took part in many different cinematic movements and eras during his illustrious reign as the king of thrillers, and much of his filmography lends itself to be debated about: which of his works are the best of their kind? When it comes to the silent era, it’s the only certain part of Hitchcock’s career: The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog is undeniably his greatest achievement of this time period. Incorporating elements of the legend of Jack the Ripper with the visual spectacle of the late silent era, The Lodger is a hard edged murder nightmare that creeps into reality. Hitchcock would go on to do masterpieces, but The Lodger was an early sign that he was demented enough to be the best filmmaker of his kind.

48. The Adventures of Prince Achmed

Before Walt Disney took over the world of animation, very few feature films of the medium existed. The oldest to actually still exist (and one of the first to be made period) is The Adventures of Prince Achmed: a passion project by wife-husband duo Lotte Reiniger and Carl Koch. Told entirely by moving silhouettes against tinted backdrops, The Adventures of Prince Achmed is so magical despite its limitations (its animation is done by movable cardboard and stop motion techniques). As if you’re midway between hearing a fantasy tale and living it, this animated wonder from the silent era places you in a trance the entire time.

47. The Golem: How He Came into the World

The start of German expressionism was certainly an experimental process with different results. The ‘20s wound up with something like The Golem: How He Came into the World, which remains such an anomaly of the horror genre. It’s also a prequel to two other Golem works by the Golem himself Paul Wegener. The best film of the bunch, How He Came into the World feels a bit nobler than the other efforts, elevating the character into this singular kind of cinematic imagery (to match its mythological origins): the Golem (in this film) is created as a guardian of the Jews of Prague during the middle ages. What The Golem as a film does is provide a unique viewing experience that really is of its own nature.

46. Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ

It might be more common to champion William Wyler’s 1959 Ben-Hur, and I don’t mean to be otherwise. I just like the original silent film a little more (which Wyler actually worked on as an assistant director for the two-tone Technicolor passages, hence his future devotion). Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ is quite similar to its ‘50s remake, but much more concise and deeply rooted with its Jesus Christ subplot, making stronger parallels between his life and that of Judah Ben-Hur. The chariot sequence is also just as glorious, and that’s also important (well, obviously, since it’s one of cinema’s finest sequences, and either film is applicable for that title for different reasons).

45. The Freshman

Of all of the characters Harold Lloyd played (mostly named Harold, obviously), one that worked really well (even more than others) was new student Harold Lamb, who sticks out of his university campus like a sore thumb. In The Freshman, Lamb is just trying to be liked: a simple goal we all face on a frequent enough basis. The main difference is we’re not this guy, who is so clumsy and full of bad luck, that it seems virtually impossible that they will come out of any situation alright. Well, Harold Lloyd and his comedic brilliance help make a seemingly negative premise and make it positive almost miraculously; as if Harold Lamb is so off that he accidentally reverts the common nature of things and comes out on top.

44. Heart of an Actress

Germaine Dulac used her films to convey important feminist ideologies in a time when film industries were willing to push back at any cost. She took the medium head-on in Heart of an Actress, where she places females and males in the entertainment field and illustrates them as separate metaphors: a female actress doing whatever it takes to keep going, and male dominance that stymie her every attempt. A bit more literal than some of her efforts (which ranged from poetic to full on surreal), Heart of an Actress was a more blatant message by Dulac that carries a huge punch that can still be felt.

43. The Toll of the Sea

We’ve reached the only fully colour film on this entire list (a different era from the rest that I’ve covered so far): The Toll of the Sea. At the forefront is the legendary Anna May Wong, who turns this humble picture of heartache and makes it a cinematic fable for the ages (particularly the unforgettable moments of self sacrifice that will stick with you forever). Part of the film was lost and reconstructed by preservationists as much as possible (it still remains incomplete, but likely as full as we will ever have it); it still carries the power to blow you away regardless.

42. Seventh Heaven

Frank Borzage won the first ever Academy Award for Best Director for Seventh Heaven, and it’s easy to see why over ninety years later. His ability to create a duality between the film's subjects and their surroundings feels mystical, as if we’re witnessing both the euphoria between the two leading lovers and the disgust of the world that shuns them both individually. Seventh Heaven loves displaying circumstances that are against-all-odds, but Borzage never allows these sequences to feel unbelievable. You're a part of this reality, where there is magic to be found even amidst the worst hatreds of humanity.

41. L’Inhumaine

There aren’t as many cinematic paradoxes like L’Inhumaine, which continues to feel as empty as it is profound. Like an elaborate diorama decked out in Art Deco designs, Marcel L’Herbier’s polarizing silent epic is like a satire of the very social circles of the roaring ‘20s that it tried to be a part of. We can see why looking at L’Inhumaine head on might be puzzling, but I’m more fascinated by its meta form that is as self destructive as some of its players. Let’s face it: the film was always meant to be art before story, even with its narrative depictions of belonging. L’Inhumaine is such an anomaly, because its essence is created entirely by its sets and style, but it’s this same art that swallows its performers alive. It’s clearly not for everyone, but I love it and its unorthodoxy.

40. Wings

The very first Best Picture winner (rather, the Best Picture, Production award, the only year that this category existed), William A. Wellman’s Wings is such an extraordinary silent picture, especially with the crazy aerial choreography and other special effects that clearly stand out amongst its peers. This World War I epic is able to balance out its personal love triangle story and the wide scope of Earth in a competitive standstill. Both tales merge in a climactic fashion, in the kind of way that would have appeared overly theatrical or synthetic in other films. Wings, however, was made by a cast and crew that was aware of the best ways to tell compelling stories, either by intimate moments or spectacular battles in the air.

39. The Cameraman

Oh, why, Buster Keaton, why? It’s so unfortunate to see how the comedic superstar’s career was destroyed by an uncompromising MGM, who went against his artistic visions on every instance. This happened because of the one instance where Keaton was able to fulfil his own ideas without any hindrances: The Cameraman. One of his best pictures, this meta comedy about “Buster” using the art of film to get to where he wants (via MGM in the film, no less) is arguably Keaton at his most poignant symbolically. It’s a shame that this is now the visible full stop of the golden years of Keaton’s filmography, because it is an excellent film full of promise that more works like this were coming (and they never did).

38. Arsenal

The strongest entry in Alexander Dovzhenko’s Ukraine trilogy, Arsenal is somewhat in the middle of the storytelling spectrum. It’s not as symbolic as Earth, or as literal (albeit poetically) as Zvenigora. Rather, Arsenal is mightily political upfront, but it strives to be artistic whilst doing it. The most difficult of the three films to watch, Arsenal is certainly in line with other Soviet commentaries of its time (extreme close ups, anger and all). In a way, the formation of the Ukraine trilogy is almost art in and of itself: it begins with a thoughtful idea, carries out its anguish midway, and ends with a gorgeous rephrasing of all that came before the resolution. Arsenal is that fuel that Dovzhenko needed to really get past the wartime turmoil he was holding still.

37. Spies

In a strange way, silent cinema can be comparable with literature, in the way that visual images are the setting-up of descriptions, settings, and characters, whilst our mind does a bit of the work via interpretation (dialogue that isn't stated on screen, here, as opposed to how everything “looks”). Fritz Lang seemed to chase after this kind of ideology, not in the ways that other directors did with serial pictures (although he did work with lengthier films as well), but rather with the pulpiness of a good book. Spies is such an example, where Lang’s obsession with depth is on full display. Getting caught in Spies’ narrative webbing is one of Lang’s achievements, but seeing the characters also fall prey (but never resolve themselves) is his ultimate form of entertainment, here; Spies is as exciting as it is damning.

36. L’Argent

Marcel L’Herbier favoured artistic sets and symbolism over literalness, which is the kind of filmmaking that cursed him with disapproval for years (and his works are still maligned, depending on who you ask). However, if there was ever someone who could point him in the right direction, it would be Émile Zola, whose novel serves as the basis for L’Herbier’s L’Argent. With Zola’s in-depth writing, L’Herbier can create an aesthetic version of the stock market without worrying about veering off course. The result — a clash between representation and exactness — is a hyperbolic-yet-powerful take on the evils and damnations of the financial districts of Paris (and, thus, the world).

35. The Thief of Bagdad

The possible opus of Douglas Fairbanks’ incredible career is Raoul Walsh’s cinematic translation of his own adaptation of One Thousand and One Nights. The Thief of Bagdad is a fantasy picture for the ages, as it carried so many innovative ideas that left filmmakers scratching their heads upon release (either that, or inspired, like the handful of directors that worked on the 1940 The Thief of Bagdad and tried to push their own innovative limits). It’s a swashbuckling opus unlike any other, and it was an open world for Fairbanks as a charismatic actor, an ambitious producer, and a seemingly-effortless storyteller.

34. Lonesome

One of the better guinea pig efforts during the transition into talking pictures (I’m looking at you, The Jazz Singer), Paul Fejös’ Lonesome is a gorgeous take on serendipity. Featuring two isolated souls that collide and spend time together, Lonesome is like an American answer to French poetic realism while that movement was on the rise (slightly before, even). Sound is reserved for capturing the setting (mainly Coney Island), as if to paint a memory, and to provide occasional moments with the voices that they deserve. Lonesome is an excursion of a film that also has to face reality in one way or another; for a little while, we were all at least in a different place.

33. The Circus

In ways, The Circus marked a significant point in Charlie Chaplin’s filmography. It is his last silent picture to actually be made before talking pictures overtook cinema for good (the transition was well on its way in 1928). Who knew if Chaplin would have made the change over himself (he eventually would, but kept reinventing silent films in the ‘30s). Before he became the full embodiment of his artistic self with City Lights, he gave the hilarious-yet-touching blueprint one last try in this silly tale of the entertainment industry, which featured his signature Tramp character on the run, and stuck in the titular circus as an act somewhat against his will. Chaplin was always the visionary, of course, and The Circus ends with a final blow heavy enough to turn your laughs into a dropped jaw of speechlessness.

32. La Roue

Abel Gance tried to mirror the ambition of his subjects with his pictures. Case in point: La Roue is a massive undertaking (its incomplete two-and-a-half hour version is long enough, let alone the four-and-a-half hour available version and the seven hour 2019 restoration). Pushing his cinematic capabilities to mimic his fascination with the locomotive technology he frames, Gance used La Roue as a way to try and break ground in silent cinema, with transitions, dynamic cuts, and image trickery. All of this would pave the way for his opus Napoléon, but La Roue is just as massive in its own astonishing ways.

31. The General Line

The second film that Grigori Aleksandrov and Sergei Eisenstein collaborated on felt like their greatest experiment of the ‘20s (when together, of course). The General Line is standard Soviet experimental filmmaking for its time, but it goes the extra mile with all of its sublime juxtapositions (symbolically, visually [through cross cutting] and literally). Likening civilians with animals (particularly cattle), The General Line is straight forward with its notions on the working class in an unfair system. Of course, it’s only natural for these two auteurs to take things up a notch, and The General Line becomes a jagged piece of cinematic art that holds up with the best Soviet silent classics.

30. Flesh and the Devil

The finale of Flesh and the Devil is so strange, as it is the ultimate definition of bittersweet. Frankly, the build up to such a moment is what renders it such a mixture of emotions. On one hand, you have two life long friends who have thirsted for each other’s blood out of jealousy, which leads up to an unforgiving decision. On the other, Felicitas — the love that is caught in between then — has a change of heart, and wills to do good. Even still, the absolute end is full of subversions, especially ones that may catch you completely off guard; it’s as if the Hollywood ending still existed, but it was reworked to the point of being borderline unrecognizable.

29. Michael

Carl Theodor Dreyer would eventually turn to melodramatic, visually stimulating silent pictures, but his films after this period would feel like straight forward dramas that would happen to have a pinch of poeticism tossed in (enough of his signature depth that would help his stories stand out). He proved this before his more expressionist era with films like Michael: a LGBTQ+ tragedy that worked with candidness before moving into an explosion of emotions. Dreyer translates the longing an artist has for a lover (the titular Michael) that is stripped from him, especially since Michael has been taken by a master manipulator. Still, Dreyer is able to find even an ounce of joy in the darkest of hours, and Michael resolves beautifully.

28. Faust

Ah, yes. The gigantic tale of Faust. The definitive cinematic version of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s play is by F. W. Murnau — who was firing on all cylinders by the end of the ‘20s — as it contains his never ending imagination on such a massive scale (particularly Emile Jannings as a Mephisto that could crush an entire city in seconds). The timeless story of a man who sells his soul to the devil for his own betterment (as well as that of his surroundings) is told exquisitely, here, with Murnau’s emphasis on all parts of the tale (including the finer details that really sell the idea that humanity is inherently tortured, and our own mythology is the attempts to understand why we behave in such ways) being as important as his ambitions.

27. The Man Who Laughs

The ancient Greeks believed in the symbiosis of comedy and tragedy, as if the human experience relied on both to strengthen the other. Something like Paul Leni’s The Man Who Laughs feels like an evolution of this philosophy, as if romance and horror could coexist together as well. Conrad Veidt’s iconic performance as Gwynplaine is so saddening to watch; his facing of society’s scrutiny is such a terrifying experience. While there isn’t much comedy here (outside of the sick joke of having someone smile for the rest of their life), Leni stripped his version of Victor Hugo’s tale of the ultimate tragedy, because he was more interested in something that both horror and romantic genres are hinged on: hope.

26. Safety Last!

Of course, Safety Last! is Harold Lloyd’s greatest triumph, and it almost feels insulting to try and insist it would be anything else (despite his other achievements). However, the one thing that we are tired of is how the film has been resorted to the one iconic image of “The Boy” dangling from a clock tower (a stigma of which I literally have not helped with, as I just used said image as my own for this entry. Oops.). The entire picture is a riot, as Lloyd faces the crisis of unemployment, and is in dire need of bettering himself and proving his worth to his one true love. Then, he takes on the kinds of fears we’ve all had: bad first days on the job. Safety Last! is far too relatable to most of us who have had to do more than just our job description to get by, and it’s Lloyd’s indisputable opus.

25. Strike

The first feature film that Sergei Eisenstein created was the precursor to his masterpiece Battleship Potemkin. Strike is — unquestionably — just as inventive and as startling as the former, and it’s so difficult to separate the two films especially since Strike was released only months before. It’s fascinating to see the ideas of cross cutting juxtapositions and montage innovation stew in this revolutionary political thriller, like Eisenstein was trying every (great) technique and stringing a tale of an uprise together with them. It’s difficult to say that Eisenstein went on to better things after Strike (if he did, the difference is only marginal) because he was already so forward thinking. Eisenstein wasn’t meant for film: he reinvented film to make himself at home.

24. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

When motion pictures were figuring out the particulates of feature epics, there were obviously some interesting results. One such experiment that feels very in-line with how war films operate today is Rex Ingram’s mightily influential The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. This tragedy is hinged on the then-recent recollections of World War I, as the world was still coming to terms with their ugliest moment of their time. Ingram’s approach is as stylistic as it is upfront: it honours the fallen whilst arguing against the necessity of war altogether. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse also contains the finest inclusion of Rudolph Valentino, who was taken from us far too soon only five years later.

23. The New Babylon

Many political films of the roaring ‘20s vowed to look ahead, as if the heightened art trends and innovations held the key to where we were going. Otherwise, they looked a little bit backwards, mainly at significant moments in American history. Then, there’s The New Babylon by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg, which is allegedly about the Paris Commune of 1871, but it’s really a comparison to the archaic ways of the earliest days of civilization. Both filmmakers take an almost orphic approach by staging two partners that are split apart by a political crisis and complete chaos, only to have each instance of them trying to reconnect result in their own curse. The New Babylon was meant for the now, but it carries many mythological connotations.

22. Sherlock, Jr.

Some of the best films are about, well, films: either the creation of motion pictures, or the adoration of the medium (straight from the biggest cinephiles themselves: filmmakers). Buster Keaton’s most honest picture he ever made was his love letter to the theatre with Sherlock Jr., where a cinema janitor’s dream becomes his own film. In return, this film-within-a-film is Keaton’s most self aware directing, containing some of his greatest stunts (the bicycle sequence is my personal favourite of his) and wittiest humour; all in the name of art and entertainment. In other Keaton features, his character was just a magnet for odd situations. With Sherlock Jr., he was the ideal poster boy for misfits everywhere, and thus becoming the actual face of slapstick comedy.

21. Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror

On one hand, F. W. Murnau’s adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (with names and minor details changed ever so slightly) is a horror film staple that helped push the genre to new, shadowy heights past the art-heavy angle of expressionism. On the other hand, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror is a full embodiment of German experimental cinema, with its creative framing of shadows, jump cut illusions, and gothic imagery. Murnau never felt pigeon holed by his roots because of his willingness to experiment, hence why Nosferatu — like other Murnau features — is such a singular experience. If anything, horror filmmakers henceforth wanted more of this new realm that Murnau accidentally created, rather than the blueprints he tried to step away from.

20. The Gold Rush

Of all of the films Charlie Chaplin made, The Gold Rush was the picture he was the most proud of, and it’s easy to see why. Its standout moments (the iconic “rolls dance”, for instance) were fine, but they still worked as parts of an outstanding whole: a depiction of his Tramp character within the titular event of the late nineteenth century, for a 1920’s world that needed this empathy. Chaplin would take this silent classic and reformat it with narration, editing, and an official score (all made by him) for rerelease in the ‘40s; clearly, it’s the time that he fully felt the impact he could have on viewers, and wanted to capture that again with even better tools at his disposal.

19. Die Nibelungen

Fritz Lang felt seemingly unstoppable after his thriller epic Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, and the sky was the limit for him. Before he would take on the future with Metropolis, he aspired to set the tone for fantasy films in cinema. While the Die Nibelungen series didn’t quite leave its permanent impact on its genre that Metropolis did with science fiction, this two-part achievement is still extraordinary, and similarly has transcended the test of time. If anything, this is my way of saying that Die Nibelungen has to be considered amongst Lang’s finest works, particularly because of its mind boggling artistry and its godly scope; it’s a must-watch in the history of fantasy films, without question.

18. The Phantom Carriage

Amidst the cinematic race between the United States, France, Germany, Russia and some other contestants, there was a small opening for the Swedish film industry, thanks to the groundbreaking works of Victor Sjöström, whose breathtaking surreal picture The Phantom Carriage continues to reign as an iconic moment in the nation’s filmic history. The grim depictions of one’s impact on others due to their actions is represented by another realm (told gorgeously through ghostly double exposures). As a drama or somewhat of a horror (this did influence the climactic moment of The Shining, after all), The Phantom Carriage is an overwhelming tale of time and how we spend it.

17. The Big Parade

Not even ten years after World War I wrapped up, King Vidor — with the help of veteran Laurence Stallings — created the greatest silent film version of these events with The Big Parade. This war epic takes its time to set up the immensity of being in the middle of battle, particularly with so much personal connection that one would fight for (loved ones, family, their country). The Big Parade is absolutely frightening, especially with its parallels between the dismissive ways fighters are set off (as if things will go back to normal once they return), and how changed veterans are once they return; it’s a bold comparison, especially with the Great War still in the minds of many by this point.

16. The Wind

It was only a matter of time that Victor Sjöström was integrated within American cinema once he broke out of the Swedish film industry. Still, he had the absolute nerve to also dominate Hollywood, too. He perfectly captured the tensions between different parts of the United States, by representing an outsider (played by Lillian Gish) trying to find familiarity in her family (of whom she is visiting), only to find herself still isolated. Her quest turns into an exhilarating parable that transcends past the capabilities of what a basic narrative can hold, so Sjöström gets symbolic to match. The Wind was an outlier understanding of American storytelling better than most examples that actually came out of the United States at the time.

15. The Kid

The Kid has become one of Charlie Chaplin’s strongest efforts over the years, mainly because it carries so much warmth, we feel. As funny as the film is (particularly The Tramp’s many earnest-yet-awful parenting attempts), The Kid is also a tale of love as well, between a destitute man (who can barely take care of himself) and an abandoned baby that he cannot help to leave to die. It’s the one Chaplin film to feel like an extension of his earlier short films (granted, this was released in 1921), so you can argue this was the filmmaking great’s attempt to fully figure out the language of the feature motion picture; we’d argue he passed the test with flying colours.

14. Dr. Mabuse the Gambler

Where do I even begin with Dr. Mabuse the Gambler? Fritz Lang’s obsession with this hypnotist psychopath started here, with this four-and-a-half hour dystopian thriller, before carrying on to his multiple revisitations down the road. Can you blame him? It feels like an impossible task to create a character — nay, a villain — this pulpy that it can exceed past the film’s confinements and feel like its own literary legend. Whenever Dr. Mabuse isn’t on screen, you can feel his presence still. Even though Lang was conquering genre conventions, it’s the odyssey of Dr. Mabuse’s quest to have complete power that he couldn’t ignore (in the same way that I couldn’t shake him off either).

13. A Page of Madness

Teinosuke Kinugasa’s A Page of Madness is one of the great destroyers of conventionalism during the silent era. Even with entire nations that were vowing to get creative, it’s a film like this one that really broke the mold of film as a visual art form. Trapped inside of an asylum, the film uses its setting and psychological nature to distort itself as much as possible, making every single shot either stunning or frightening. Kinugasa’s vision never lets up, either, rendering you nonplussed to the point of questioning your own sanity by the end of the film. Obviously, the passing of time shouldn’t affect how we grade films, but attempting a silent film as warped as A Page of Madness in 2021 is a departure from your norm I highly recommend.

12. The General

If comedy could ever be epic, it would probably look something like The General. Often agreed upon as Buster Keaton’s zenith, this Civil war comedy places the deadpan mime and his usual antics onto (and in front of, and on top of, and…) a locomotive. Yes, Keaton has attempted many dangerous stunts before, but The General feels like one long sick attempt at tossing everything at him and seeing how he fares out. It’s this nonstop level of mania that puts The General out front of the rest of Keaton’s extraordinary filmography: it’s honestly astonishing how much gets crammed in here. Had things worked out better for Keaton, I can only imagine how many Generals he had up his sleeve for us.

11. Pandora’s Box

I’ve had a number of social commentaries on the working class on this list already, and a good percentage of those dealt with the sacrifices made to get by. However, G. W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box is so self aware that it becomes borderline metaphysical, especially with how Lulu (played by Louise Brooks) begins to break the compartments of the film around her. Things get even crazier when Pabst begins to explore external connections (Jack the Ripper making an appearance is quite unforgettable), but that didn’t stop the director from exploring progressive storytelling as well. In a way, Pandora’s Box almost feels like Pabst saying a vicious “farewell” to the ‘20s (especially considering how much he veered away from the source materials) as a means of showing what was yet to come in cinema. His foresight wasn’t immediately apparent, but I’d say he was more than right ninety years later.

10. The Last Command

It’s strange to be able to proclaim that only one film is the greatest of Josef von Sternberg’s, considering how many noteworthy films he had in his signature style (which crossed over from silent to talking pictures). Alas, this decision is still a no-brainer for us, and I’ll proudly crown The Last Command as that film. Sternberg is aware of the connection that cinema can have between people, and helped make this meta take on that notion, via a Russian general’s transition into acting (Emil Jannings in his Academy Award winning role). The bridge between political commentary and the love of film is a short one in The Last Command: Sternberg’s cleverest experiment.

9. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

Ah, yes. Here it is. Likely the first feature film most Film 101 classes study. The textbook German expressionist masterpiece. Tim Burton’s well of inspiration. Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is still as unique as it was one hundred years ago, no matter who learns of it or is inspired to replicate it. Wiene’s angularly depicted, warped-aesthetic playground within the mind of the deranged was quite the way to open the new decade, especially shortly after feature films were first being figured out. There’s also Dr. Caligari’s gall to toss what is allegedly one of the first twists in film history right at you; it’s a bit expected by today's standards, but that doesn’t make the film any less extraordinary.

8. The Crowd

There aren’t many basic depictions of life that resonate as largely as King Vidor’s The Crowd even to this day. It’s frankly unreal how breathtaking it is, even with how regular much of its story is. There are the occasional metaphorical images (I’m thinking of the ones that resemble the monotony of everyday work, and the overwhelming sensation of being one-in-a-million), but The Crowd is also sure to highlight the joys of being alive as well. Maybe that’s what makes The Crowd so special: its indescribable sense of balance that we can so quickly identify with. Even now, the yin and yang of the American way of life hasn’t been showcased as well as Vidor’s classic, and many other attempts feel pale in comparison.

7. Napoléon

There's something about epics of the silent era that feel unmatched; it’s as if the exploration of what massive filmmaking can be ended up with so many strange results. One such case is Abel Gance’s Napoléon, which is five-and-a-half hours in length, and has a final act that requires three screens to be projected on to create a gigantic visual experience. It all starts humbly with a snowball fight, resembling the young Napoléon Bonaparte’s fixation on power from day one (and I can’t help but see it as Gance’s way of finding an identifiable leadership quality he wished to carry out as a filmmaker). Napoléon is a cinematic experience unlike any other, but we can still empathize with why Stanley Kubrick’s own version didn’t come to fruition: some tales just can’t be told simply.

6. The Seashell and the Clergyman

In the same way someone like Agnès Varda was overlooked as an even earlier contributor to French New Wave than those credited, I feel that Germaine Dulac suffered the same fate. Un Chien Andalou is perfect, yes, but so is The Seashell and the Clergyman, which predated the former by an entire year. Dulac’s surrealist masterpiece captures the nightmare of a man of faith falling for his perverted urges and objectifying a general’s wife, forcing us to deal with his twisted fantasies. Via Dulac’s gaze, The Seashell and the Clergyman is a feminist opus full of abstract scenarios, allowing your mind to piece all of these images yourself (and falling victim to the darkest corridors of your own psyche).

5. Greed

Sometimes, reviewing classic films is a challenge. What is a film? Is it what we see when we watch the work, or is it how the picture was initially intended? So, yeah, I can guarantee that most people (or even all people) have not seen Greed as Erich von Stroheim intended: ten hours and all. Even the Turner Classic Movies version is only four hours, and full of still images in place of many missing scenes. Still, even a Greed that is substantially lost — and not even a motion picture for much of its duration — is one of the silent classics that every cinephile needs to see. The golden tinted moments (where a lust for riches overtake our sense of normalcy), the ever-so-gradual descent into a financial hell, and the deterioration of morality in the name of success are impactful in any capacity. I wish we can see the complete Greed one day; even four hours isn't enough.

4. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans

When other German filmmakers were chasing the ways of expressionism and beyond, F. W. Murnau was finding new ways to enhance the norm. He did try his hand at genres with works like Nosferatu and Faust, but his greatest triumph is Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, which plays more like the rediscovery of the cinema of attractions (Tom Gunning’s theory of the filmic medium surpassing the use of a narrative). Sunrise uses a marriage that has now dwindled to complete ruination, and finds the joys of falling in love all over again (with the use of recorded sound to enhance these adoring moments like memories to be held onto until the end of time). Murnau’s use of his expressionist roots to detail everyday life is timeless.

3. Battleship Potemkin

Of all of the revolutionary Soviet pictures of the ‘20s (and even beyond), there is one that is the go-to picture for film schools and film historians alike: Battleship Potemkin. Sergei Eisenstein’s insurmountable picture is blessed with one of the most powerful scenes in all of cinema (the Odessa Steps sequence), but it proves its worth by being consistently brilliant (and nerve wracking) for the entire picture: from mutiny to outbreak. The groundbreaking use of montage (amongst other editing techniques) has made Battleship Potemkin a must for curriculums; Eisenstein’s masterful storytelling has rendered the film a must-see in Russian cinema.

2. The Passion of Joan of Arc

The Passion of Joan of Arc is the pinnacle point for so much of the silent era. It’s easily the masterpiece of Carl Theodor Dreyer (one of film’s strongest auteurs), and it contains the most powerful acting in all of the era (Renée Jeanne Falconetti’s work as Jeanne d’Arc remains a top candidate for greatest performance ever). When other films went artistic, The Passion of Joan of Arc found impact in the real, opting for a confrontational look at a misunderstood martyr in her final hours alive. This is achieved with extreme close ups, mind boggling pans, and other techniques that have become normal parts of filmmaking now. There’s a reason why The Passion of Joan of Arc hasn’t lost any of its staying power: Dreyer’s awareness of what makes cinema puissant well before many other directors caught on.

1. Metropolis

Okay, so we have a bit of an obvious first place pick here, but hear me out. Consider how many different ideas and experiments took place in all of the 1920’s, as a means of exploring how far one can go within the cinematic medium. We’ve seen a whole range of different attempts through rising filmmakers, nations wanting to come out on top, and citizens with something to say in this fresh artistic medium. With all of this in mind (and the crazy competition throughout these ten years), it’s honestly a miracle that Metropolis is the absolutely certain answer as to what the best film of the decade is. Think about it: to be this certifiably profound, impactful, innovative, and monumental in a decade full of creation and prowess with such certainty over ninety years later has to mean something.

Fritz Lang’s magnum opus, in short, changed science fiction (on any front, and not just in film) forever. Period. That’s the least that it did, and it’s already an extraordinary achievement. Every sci-fi piece since has been tethered to Metropolis’ depictions of classes in a futuristic setting, including the dystopian sufferings of the impoverished and the godly paradise of the upper class (as if it were all but a dream). The way Lang painted a future civilization in all of its highest of highs (flying vehicles) and lowest of lows (people who literally live in the depths of the city) is an image countless storytellers have copied, parodied, and aspired to best ever since, but every attempt pales in comparison. Is Metropolis the best silent picture ever? Yes, but it’s so much more than that as well. It keeps up with any masterful talkie and shines as one of the greatest films ever made.

The greatest joy of Metropolis is how it has received a number of rebirths over the years, as if viewers have been inspired to create life (as is done in the picture). These include new original scores and remixes of the picture. These also match the discoveries of new portions of the film that were previously lost, and Metropolis only continues to get better and better with each reunited piece; we’re still missing portions of the film, and it’s perfect regardless. At this point, Metropolis is like a miraculous artifact that you’ll never fully know the story of, but it doesn’t matter. What you have is pure brilliance enough. In a picture full of steel, dark magic, machinery, and death, there is a link between soul and thought: the union between the hard workers and the fortunate dreamers. Fritz Lang embodied all of this as a director, and there’s no greater piece of evidence of this than Metropolis: the greatest film of the 1920’s.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.