The Best 100 Films of the 1950's

WRITTEN BY ANDREAS BABIOLAKIS

Seventy years ago, 1950 hit. It was the middle of the century. After the second World War came the urgency for artists to share their sides of the story, from all over the world. Meanwhile, in good old Hollywood, the Hays Code continued to dominate features; however, this stifling of creativity led towards large epics that stayed within these rules, or rebellious works that stepped on them as much as was possible. Then came television, when the idea of the nuclear family could be sold in many capacities, and was transferring in its own little way onto the bigger screen. Technicolor was now becoming more popular, but the full transition to colour just wasn’t happening yet; the past was being held on to.

Strangely enough, the 1950’s were full of many changes, yet the decade acts mainly as a bridge between the 1940’s (when Hollywood was at its most signature state, and world cinema was starting to really leave its own mark) and the 1960’s (when every rule was destroyed, and all styles merged together to revitalize cinema). Nonetheless, the ‘50s still carry so many powerful works, from golden age icons that were making their final statements, to auteurs of the future that were ready to break this medium wide open. One thing to remember is that 1950 was also only twenty three years after talking pictures became mainstream and overtook the silent era completely, so the advancements of cinema are hugely noticeable with this comparison.

Before counterculture, culture was defined in other ways. Music was starting to find its own footing. Again, television was born, and changing how visual storytelling was consumed. There was a certain identity that youths were developing, and the world was following suit; with so many years of civilization seeing (in motion) how the world was run, things like fashion and decor changed like never before. Now, I do have to remind the fact that many narrow minded ideas and stereotypes were still being promoted above the voices of the marginalized around this time, so “culture” was still skewed enough to not encompass all ideas. Still, I find so much context in these following one hundred pictures, which all embody the same idea that most ‘50s film carried: this is the best that cinema will get, and the formula has been perfected. While that wasn’t the case and the medium evolved, you will certainly find many of cinema’s finest hours here, as these selections are all exemplary in many ways. Far from the end of the road for film, but rather the end of a specific chapter, the ‘50s carry so much of film’s golden age in a myriad of ways, as well as world cinema’s influence overall. And now, it’s time to dive right in. Here are the best one hundred films of the 1950’s.

Disclaimer: I haven’t included documentaries, or any film that is considerably enough of a documentary (mockumentaries don’t count). I haven’t forgotten about films like Night and Fog or The Mystery of Picasso. I’m keeping them in mind for later (wink wink).

Be sure to check out my other Best 100 lists of every decade here.

100. The Band Wagon

Knowing one’s limitations towards the end of their career can be a difficult torture to endure. For Fred Astaire, that recognition is handled extremely well in The Band Wagon (ironically, he’d still act in some musical pictures afterward). In all honesty, the film is a straight up celebration of one of the genre’s greats, conducted by Vincente Minnelli in his prime. Even though the tale of Faust is at the heart of this rebirth, there is nothing as foul as the the sale of one’s soul to the devil; just a master showing that he still has what it takes to compete with the younglings, in the heat of the Technicolor boost of the Hollywood musical during the ‘50s.

99. Rio Bravo

Howard Hawks always specialized in bright dialogue, and Rio Bravo has that in spades. I feel it’s an opportunity for the speech wiz to place these conversations in a western setting, turning untouchable cowboys into guys you want to hang out with. This, in return, was a retort for High Noon (featured later in this list), as John Wayne and company wanted to bring back a certain Americanness to the western (which was clearly heading towards revitalization territory). You still know everything’s going to be okay, but Rio Bravo makes every step of the way there worth it, particularly because every moment is either exciting or just simply fun.

98. The African Queen

Even though both Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart were acting for many years before, their union in The African Queen felt like an actress of the (then) now paired up with a veteran of yesteryear. They both enhanced each other to great heights, with Hepburn channeling the next wave of her acting career (one full of dramatic chops above charm) and Bogart feeling the most different he has ever seemed; he won his only Academy Award for this film, which was shortly before his death. John Huston feels like a daring coach, going with a line up change to see what would happen, and the chemistry at the heart of the explorative The African Queen keeps the adventure stimulating and impactful throughout its entire duration.

97. Sawdust and Tinsel

Now I flip onto the start of Bergman's career, and there are different starting points where he went from aspiring visual storyteller into a game changer. For us, one of the first films of this sort was Sawdust and Tinsel, which remains by far his most underrated achievement. His first partnership with cinematographer legend Sven Nykvist resulted in both visionaries pushing themselves beyond their limits; Nykvist toyed with reflections and lighting, while Bergman dug deeper into the hearts of his subjects. While Summer with Monika was his first proper introduction of his capabilities, Sawdust and Tinsel was his effort to really test the waters; it’s no wonder why his classic era only strengthened after this release.

96. The Hitch-Hiker

The Hitch-Hiker is a stirring work by Ida Lupino, who achieved a number of landmarks as a female filmmaker. In such a short amount of time, her noir opus’ focus on the kidnapping of two friends — by the very hitchhiker they offer a ride — manages to turn stomachs and raise goosebumps. It feels strangely like a too-real, super long episode of The Twilight Zone, and it’s no coincidence that Lupino was also the only female director of any episode of the long running classic series. She clearly knew how to find the scarier corners of the mind via realistic scenarios in a time as safe as the ‘50s, especially since The Hitch-Hiker holds up far better than many other end-of-the-line noirs around this time.

95. Godzilla

We all love Godzilla, and our selections of our favourite films all vary. I think the one variable that remains constant in all of our lists is the original film, which is the only one to feel like a societal statement more than a barrel of building crushing fun (which is not a problem, I might add). Godzilla was a response to the nuclear bombs that hurt Japanese civilians for decades to come, and the repercussions were already strong enough to detail in such a symbolic way. So, the titular monster is created by the evils of humanity, and this monster epic is the result. Is it nice to have the fun films that came after? Sure (I’m team Mothra, by the way), but this first film will forever be a poignant comparison of real world terrors in a beautiful-yet-exciting way.

94. Black Orpheus

Oddly enough, the 1950’s housed two imaginative retellings of the mythological tale of Orpheus and Eurydice. The first such film is a greatly creative, lively rendition by Marcel Camus known as Black Orpheus, and it is relocated to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. With so much emphasis on the musical side of the legend (without becoming an explicit musical), Black Orpheus focuses so much on the celebration of life before it becomes a fate that is being toyed around with. Camus’ vision became a source of melodrama at the end of the decade, one that affected many viewers that arrived with glee, and left with heartache.

93. The Nun’s Story

On paper, Fred Zinnemann’s The Nun’s Story seems like it would be the tired story of a fish-out-of-water who isn’t fit for the title. If anything, the film dives so much deeper than that premise alone. Amidst gorgeous settings is a diary entry of the slow realization that the world is completely different than one imagined, and this is why one’s purpose has to change (rather than a lack of qualifications). Based on the confessions of real nuns that have been through it all, The Nun’s Story is an epic of internal sacrifice, and understanding the complexities of the world in whole new ways every time. This boils down to the biggest dilemma at the epicentre of the film: even if one is devoted, is this how they want to approach their faith?

92. Ace in the Hole

It seems that Sunset Boulevard was Billy Wilder’s ticket to complete freedom. There’s a clear distinction between the lighter films of his from the ‘50s onwards and the dark material that he worked with more frequently previously. I feel like it’s because of Ace in the Hole: the followup to Sunset Boulevard, where Wilder aimed to be more savage than ever before (and after, clearly). Illustrating the corruption of someone trying to be good at their job, Ace in the Hole takes a cynical premise (a struggling reporter that exploits a man trapped in a mineshaft to rise to the top) and runs with it to the point of pure sickness. Not once does Wilder detail this satire as surreal or strictly comedic, so the extremities are sure to drive you to panic. Oddly enough, the heart found in the climax only makes Ace in the Hole even more pessimistic; what was it all for?

91. Shadows

John Cassavetes clearly had a vision when he switched from acting to filmmaking and made Shadows: debatably the first independent film as we know them now. It isn’t even about the budget anymore; Shadows in style feels like the blueprint of indie classics from thereon out. Maybe it’s the focus on the minimalism that a lack of financing can bring, or the shift of specific types of dialogue to the forefront of a picture, allowing the characters themselves to become the story. It was also racially progressive, featuring a mixture of cultures and backgrounds into every day settings, whether bigoted audiences were ready for it or not. Cassavetes was always thinking ahead, but he was twelve moves ahead with Shadows.

90. Nazarin

The 1950’s was an interesting time in Luis Buñuel’s filmography, because it’s the time where we could find his greatest straight up dramas (okay, with occasional surreal elements, naturally). Nonetheless, Buñuel could never turn away from discussing class or religion, and Nazarin is no different. As if Buñuel was inspired by Ingmar Bergman’s then-latest cinematic discussions, Nazarin is an approach on religious morality that feels uniquely agnostic; how could one find themselves in this position if they try to do all of the right things? It’s a less savage attack on organized faith than what Buñuel could dish out, likely because Nazarin is a sympathetic olive branch to say that he sees those that want to be good to heal themselves and be saved.

89. Smiles of a Summer Night

Legend tells us that Ingmar Bergman was ready to die if he didn’t connect with large audiences with Smiles of a Summer Night (he did have a grim sense of humour, after all). Well, luckily for everyone, it was a sensation, and the first film of his to actually put him on the universal map. A sex romp dramedy that features everything from swapping to Russian roulette, Smiles of a Summer Night is a cauldron with a mixture of clashing ingredients, and Bergman’s search for the best results amidst this calamity. The next day, it’s all over, as if it were all a dream, and there are zero repercussions for exploration. It’s a rare time where a Bergman film doesn’t burrow itself into your head with existential questioning for the rest of your life, and it’s a pleasant change of pace.

88. Giant

There might not be a title more appropriate than Giant when it comes to George Steven’s Hollywood opus. At over three hours in length, many years depicted in the story, and a trifecta of Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson and James Dean, Giant is ambitious in every single way. That’s interesting, because so many of the finer qualities come in the little things: the interactions between different characters, and the progressions of each person as time goes by (indicative to what they have survived). In a time when many large scaled epics lost sight of the time periods these characters were experiencing, Giant explores each chapter thoroughly, as if we have aged with these people ourselves. In that way, it’s a beautiful prophecy of what could have been with James Dean, who died way too young before the completion of this film.

87. A Night to Remember

Possibly the best film about the Titanic (yeah, I said it), A Night to Remember zooms in so much on the responses of many passengers from their own perspectives. Do we see the ship sink from the outside, and knowing what the crew knew? Yes, but we also get an understanding viewpoint of what the many voyagers on board felt, including the lies of false alarms and a lack of concrete information at all. The mad panic becomes much more understandable, and the respect for both the fallen and the survivors is large; this feels much more about everyone. Sure, maybe a lot of retrospective looks at the historical crisis have been noteworthy, but A Night to Remember seems to do this event the utmost justice.

86. Salt of the Earth

Labeled as a progressive film that pushed feminist ideologies (particularly the roles of women in society, and the mistreatment of maternal figures), Salt of the Earth was an important feature for its time (only to be bogged down by blacklisting for supposed communist connections). With every topic raised in the film, the female perspective is always considered in equal amounts, allowing for a complete devotion to what Herbert J. Biberman was seeking; he also worked with neorealist blueprints, employing non-performers to tell their own stories in his feature. At times, Salt of the Earth feels more like a documentary (or at least a docu-fiction) because of its prioritization of voices above aesthetics and theatrics.

85. The Day the Earth Stood Still

Robert Wise started the decade off with The Day the Earth Stood Still: a political comment cleverly disguised as a generational appropriate science fiction flick. Sure, there are otherworldly beings and spacecrafts, but really this film is about the dealing of conflict on a large level, and it's actually quite obvious (even from the title alone). What does the “other” (outside of Klaatu, who interacts with the humans) do? They await the human response. The Day the Earth Stood Still is anchored by the choices that humans make in such a situation, and all of its outcomes after the initial introduction derive from what comes next, like a series of dominoes toppling over in whichever direction.

84. Johnny Guitar

Even though Nicolas Ray’s Technicolor western is named after the character played by Sterling Hayden (who is awfully slick in this film nonetheless), Johnny Guitar is owned by Joan Crawford in every way. Crawford was still dominating the screen decades into her career, including this western that is hellbent on misconceptions and lies. Even with a majority of the film based on discussions — and the figurings out of where everyone actually stands — the cinematography pops so much, turning even a regular conversation into a ‘50s visual feast. That’s just the spice on top, with the tensions between characters brewing up to a boil at just the right moments.

83. The Big Heat

Fritz Lang complied with Hollywood’s pickiness when he started making American works, so it was only time that he brought some sort of European influence to his classic noir films when the genre was finishing peaking. The Big Heat feels more like one of the French noir films out at this time than one from the United States, but that’s because Lang — like always — was one to think outside of the box. Amidst the boiling temperature of directors fed up with the Hollywood code is a film like The Big Heat, which toys with how much it can get away with (particularly its scorching climax and aftermath: indicative of the bold moves noir films would make). Underneath its danger is a stunningly shot film that elevates The Big Heat above its noir contemporaries.

82. La Pointe Courte

Well before French New Wave was Agnès Varda’s fixation on breaking the conventions of cinema, and La Pointe Courte feels as modern as it ever was. Driven by the air that fills up each scene more than anything else, Varda’s early vision was a prophetic look at the incoming series of waves that deviated away from the epic, overwhelming nature of the most successful films of the decade. Instead, Varda crafted poetry and curiosity, allowing viewers to look around and not be told how to particularly feel. It was a foreign concept for sure, and many French filmmakers quickly followed suit. There's no question about it: When it comes to French New Wave, Varda was first. As for Left Bank films, Varda was the queen.

81. The Ogre of Athens

Naturally, Greek cinema has a bit of a dark sense of humour. Nikos Koundouros proved this early on with the under seen The Ogre of Athens: a grim satire that's an inch away from being a Monsieur Hulot comedy, and a hair away from a fully fledged noir. Instead, it's a crime satire about being in the wrong place at the wrong time, the film, like the unsuspecting lead, just runs with the predicament. I wouldn’t call The Ogre of Athens hilarious outright, but much of its hilarity is gasp worthy, considering the chain reactions that make up the plot like a runaway train; all of the comeuppance is unstoppable, because the criminal underworld never sleeps.

80. Orpheus

I mean this in the best way possible: Jean Cocteau was always looking backwards while he was aiming straight ahead at the future. Orpheus was a latter masterwork of his that proves just this. It exemplifies his adoration for old style fantasy elements in cinema, particularly with the modernization of the mythological tale of Orpheus and Eurydice (here we go again!). At the same time, Cocteau always wished to be ahead of the pack whilst being nostalgic, so these old techniques are refined to make something gorgeous. Orpheus is singular in this respect, because Cocteau wasn't working with the pack but rather for himself, thus conjuring a modern fable full of aesthetic brilliance.

79. Late Chrysanthemums

When we reach my 1940’s list, you will see many films in response to the second World War. In the ‘50s, there continued to be a poetic wave of films from Japan that continued these discussions. Late Chrysanthemums attempted to carry on this topic in a multitude of ways, via a handful of stories told by four geishas after the war. In Mikio Naruse’s opus, there is one main concern: how do we survive after everything and everyone has been taken away from us? There are a few cases in which Naruse tries to tackle this dilemma, and they all resonate differently, proving that circumstances affect everyone in their own ways. Late Chrysanthemums was only four takes in one film, and yet they all stand alone; you can only imagine the billions of ways that war changes us individually.

78. Funny Face

After Fred Astaire consoled Debbie Reynolds during the shooting of Singin’ in the Rain, he was chosen to lead one of Stanley Donen’s next films titled Funny Face (this time without Gene Kelly’s directorial involvement). He was paired up with the then-blossoming Audrey Hepburn, who would have her own fruitful partnership with Donen in the near future. The duet between veteran and newcomer in Funny Face is one of the finer examples of films that are strung along by heart alone, because of both leads' abilities to wear their emotions directly on their sleeves. Donen captures these feelings in every single shot, and puts them in Technicolor, creating a musical that, well, s’wonderful.

77. Rebel Without a Cause

It might be one thing to see how Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause has become the go-to tribute for James Dean, who was taken from us far too early. It's easy to see why, since Dean took what could have been an insufferable youthful character (oh big whoop, you got called a chicken) and created a textured teenager dealing with internal conflicts; this was clearly only one of Dean’s abilities, and we didn't get a chance to see how many others he had. Then, there's the film’s ability to wring tension out of the story, and lead up to flaring tempers and shifting gazes that will crawl up your spine. Rebel Without a Cause is certainly a pop culture film, but that doesn't make it any less of a successful exercise in anguish.

76. Bob le flambeur

Considering that the ‘50s was a bit of a lower period for Jean-Pierre Melville, the fact that he still created Bob le flambeur is a testament to how brilliant the French auteur really was (and ahead of his time, to boot). At the tail end of the classic period of films noir, Melville was already thinking ahead (as he always did) and tried to finesse the genre in cinematically explorative ways. Because of his fixation with nuance, Melville actually accidentally predated the French New Wave, if anything. The editing is sharp, the dialogue is savoured, and the cinematography toys with black shadows and white lights. What was meant to be a tribute to the French gangster films that started it all became a sign of the future, considering how much of this style of filmmaking the New Wave would channel.

75. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

When done right, plays adapted for the big screen can be an encapsulation of the human experience. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof manages to perfectly bottle up the many boiling points of a dysfunctional family (that’s driven to the brink of insanity via alcohol addiction and illness). Only a small portion of the film is devoted to dramatic irony, as we're left to face the slow realizations of lies being uncovered and true feelings being revealed. All of the proverbial cats have pounced ages ago to protect themselves; they're all clawing at each other in the alley way below now. That’s what the film aims to depict: the leaping-off point of those that can no longer take it. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof manages to nail the feeling of confrontation almost too well, in that regard.

74. Strangers on a Train

The 1950’s was Alfred Hitchcock’s era to steal, after he found his signature style’s best qualities a decade before. Now, he was figuring out the endless possibilities of what mysteries and thrills life could offer. In his search, he found the peculiar qualities of two strangers meeting up and becoming entwined with one another: one man currently angry, and another permanently sick. Strangers on a Train meshes the reactionary voice of an emotional person and the outsider perspective of a listener together, to create a perverse tale of a devotee trying to dictate fate. It's a rare mystery where we see everything in front of us, and are told everything along the way; we just can't believe it's actually being carried out like this.

73. Diary of a Country Priest

Usually, the works of Robert Bresson are succinct and brief; they carry a wallop in short durations. However, he had much to say through Diary of a Country Priest, since he was channelling the loss of religious belief in a religious figure. Country Priest is a slower burn than usual for Bresson, almost like he doesn’t want to believe what is happening to his subjects in this film; a piece of him is withering away when he keeps telling his story. Still, Bresson works via poetic textures, allowing you to feel every ounce of reservation in this downward spiral; as faith collapses, society grows taller and scarier.

72. Witness for the Prosecution

On paper, a Billy Wilder adaptation of an Agatha Christie legal drama seems like a fantastic idea, and you’d be right. Neither fully noir or comedy, Witness for the Prosecution is a Wilder feature that feels of its own world, but it easily holds up with the best of his works. Driven by a never-better Marlene Dietrich (and other fantastic players like Charles Laughton and Tyrone Power), Prosecution is a battle of words and wits: performers versus character arcs. The ‘50s was a fantastic era for courtroom epics (some of which you’ll see later on in this very list), and Prosecution keeps up with all of them, because there wasn’t a director that was better at pairing wise dialogue and magnetic performances than Billy Wilder.

71. Throne of Blood

I wish Akira Kurosawa did even more Shakespeare adaptations (Ran placed highly on my top films of the ‘80s). At least there was still Throne of Blood: an interpretation of Macbeth smack in the middle of Kurosawa’s creative rise. Blending Shakespeare’s dark writing with Japanese ghost lore and wartime, Throne of Blood carries all of the original story’s guilt and creates its own torment. Kurosawa’s gift for conjuring mysticism amidst panic makes Throne of Blood hit home, because the story becomes pure, dizzying hysteria. Even though he would perfect his refinement of Shakespeare’s plays, he proved early on that not many filmmakers could compete with his adaptations, truly making Macbeth his own creation.

70. Invasion of the Body Snatchers

Sure, the Philip Kaufman remake might be creepier (lest we forget that high pitch croak), but none of the other versions come close to Don Siegel’s original Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Carrying all of the cheese that ‘50s horror films had whilst never losing any of its integrity or effect, Body Snatchers might not be terrifying today, but it’s still compelling to watch. Released right in the heat of the blacklisting movements in Hollywood and all over America, Body Snatchers was both the witnessing of loved ones turning, and a warning about false accusations during witch hunts. Maybe that’s why it connected so greatly, beyond other horrors of its time: it secretly detailed fears ‘50s Americans actually held, as the news and government instilled panic amongst the people.

69. Pelli Chesi Choodu

L. V. Prasad’s classic Pelli Chesi Choodu feels forward thinking, even though it’s more of a commentary on old fashioned ideologies. A near-screwball homage driven by marital practices — particularly dowry and arranged courtship — Pelli Chesi Choodu pokes holes in so many practices (lovingly, of course). As Prasad himself was also a business expert, his opus feels like a series of pitches, proposals and transactions, all being torn apart by lovers hoping to follow common sense. Whilst never getting too silly or out-there, Prasad’s take on love feels more like a commentary on his observations growing up; I wouldn’t say the film is fully a satire, either, considering the amount of heart it carries.

68. Invention for Destruction

Karel Zeman released a number of works that are comparable to early silent shorts, hence why he has been called a successor to Georges Méliès. Even though the body of his work is worthwhile, the starting point I suggest is Invention for Destruction: a gorgeous dip into early cinematic magical territory. Built like a silent film whilst not being one fully (even the delivery of dialogue and sound is “off” for the ‘50s), Invention for Destruction takes the visions of Jules Verne and brings them to breathtaking life. It’s a rare exception where a film being dated is completely its charm; it’s exactly how Zeman wanted his living pop-up picture book. His influence is still felt in the works of Wes Anderson, amongst other filmmakers.

67. A Streetcar Named Desire

I could champion Elia Kazan’s Tennessee Williams adaptation as the breakthrough of Marlon Brando (guys, he’s considerably the villain of this film), but I want to celebrate everyone in A Streetcar Named Desire. All four characters (the others played by Vivien Leigh, Kim Hunter, and Karl Malden) bounce off each other in every single way, both contrastive and complementary. It’s no wonder that the film won three Academy Awards for its acting (the only non-winner, oddly enough, being Brando). Kazan pounced upon these opportunities to let each character shine, creating what is undeniably the pinnacle Williams feature film. Now, if only people could stop yelling “Stella!”, considering Stanley is toxic and not sympathetic (it’s a strange instance where something gets lost in translation in pop culture).

66. Fires on the Plain

Not many depictions of the second World War were willing to get too dismal in the ‘50s, given the time and Hollywood code. However, Kon Ichikawa didn’t need to abide by the code, and he took the aftermath of the war very seriously. So, he created an artistic anti-war epic titled Fires on the Plain, full of artistic shots that don’t hide the brutality of war (if anything, they enhanced them). Aesthetic to the point of being a borderline psychological experience, Fires on the Plain felt like the necessary discussion to have when words had to be minced. It wasn’t too well received at the time, but Ichikawa’s masterpiece is a breathtaking statement that is beyond cherished now.

65. East of Eden

When television was stirring up the portrait of the nuclear American family, and Hollywood was still timid enough to not push past the Hollywood Code, Elia Kazan’s adaptation of John Steinbeck’s East of Eden couldn’t have come at a better time. The woes of the misunderstood and vulnerable collide with the championed and beloved, in a juvenile story that depicts the upcoming generation of Americans that may not abide by all of the blueprints laid out before them. In its core, we have James Dean at his very best, turning Steinbeck’s story into modern day lore; he makes a character that may have been pathetic into a heartbreaking misfit.

64. Letter Never Sent

After The Cranes are Flying, it was clear that Mikhail Kalatozov and Sergey Urusevsky were a duo that just got one another; Kalatozov would run with the elements of film and life to tell a story, and Urusevsky was the cinematographer to enhance this the most. Their followup is Letter Never Sent, which was appropriately released right at the tail end of 1959 (to the point that the film is a 1960 release for a number of locations); it’s as if they were ready to keep making aesthetic pictures of the future. There’s much less hope here than in Cranes, though, as an adventure to locate diamonds turns into a dizzying spell for all of the geologists involved. On the earlier topic of elements, Kalatozov works with the Earth’s four to drive his point home (dirt, wind, water and fire all get in the way, but are shot so gorgeously).

63. Floating Weeds

If there was ever a harsh critic of Yasujirō Ozu’s early works, it was Ozu himself, who completely wrote off the start of his career. Case in point: Floating Weeds was a remake of his own 1934 film A Story of Floating Weeds (this time, with Ozu’s signature mise-en-scène and with a splash of Technicolor glory). Even though the original film feels more like a story being told, the second iteration of Floating Weeds reads like a lifetime being lived, which was of course Ozu’s primary ability in his films. This was Ozu’s evidence that he understood films inside and out now, and he revived a film of his that would have been lost in time with expertise that still hasn't been matched.

62. Roman Holiday

I’m a bit against the grain, here (not intentionally, I swear). William Wyler is beloved for his epics like Ben-Hur and The Best Years of Our Lives. However, I’m a bigger fan of the huge amounts of passion that comes out of his smaller works like, say, Roman Holiday. In a smaller amount of time, we get an entire world created just between a royal trying to live a normal life and a reporter trying to find more truth than just the scoop can provide. So, throughout Rome they wander, and so much can be read from so little. Wyler is an expert at capturing the breath between two people, and I feel that gets lost in some of his epics, but is as clear as day in a delight like Roman Holiday.

61. Apur Sansar

Satyajit Ray’s magnum opus — without question — is the entire Apu trilogy, so deciding which part is the weakest is not fun. In a silly way, the final portion (Apur Sansar) can be my candidate, only because it’s sad to see such an ambitious project wrap up. In all actuality, it’s the most dependant on the other films in the series, but it holds up greatly as its own picture. By itself, Apur Sansar is the fear of continuing after tragedy. In the trilogy, this final piece becomes a child’s development into adulthood, only to face similar crises that his family faced before him. Still, it’s truly something to see Apu as an adult and a parent, after the entire journey of the trilogy until now.

60. A Star is Born

The greatest version of A Star is Born is George Cukor’s 1954 remake that began the whole musical element of the story (originally about a movie star). It starred Judy Garland, who was staring many fears in the face by this point (a fading career, addiction problems, poverty, and more). The musical icon of yesteryear was now the revival story of all time, with a bonafide performance that remains untouchable by any standard. This rendition of A Star is Born mixes music and distress together, between a struggling artist wanting to make it big, and her ailing partner who is on their way out. Sure, most versions of this story are actually quite good, but for us Cukor’s vision is the no-contest winner that delivers the biggest wallops and carries the largest griefs; all amidst gorgeous melody.

59. Some Like It Hot

In a decade where Billy Wilder truly dominated, it says a lot that Some Like It Hot has resonated as a fan favourite of his. It was destined to be loved; Wilder himself knew this with test audiences, where he learned he had to lengthen some scenes to allow for laughter that wouldn’t stop. In 2020, the gender bending can come off problematically, particularly since a number of jokes are at the expense of sexual preferences and orientations. Otherwise, the comedy lands extremely well even today, which counters the darkness the film is willing to get to (it is a pseudo noir film after all). A screwball film willing to see how much trouble it can get into, Some Like It Hot is the most fun one can have walking on eggshells.

58. Wild Strawberries

When Ingmar Bergman was comfortable enough to explore his own psyche beyond faith alone, he created Wild Strawberries: an existential takeaway from the clutches of death and reality. Starting off with the cinematic nightmare of all nightmares, this journey film sets a tone full of fear, despite the celebratory tone of collecting a lifetime achievement award. As old unites with young (in the form of a geriatric professor bumping into various younger vagabonds), Wild Strawberries combats the dread of the inevitable with the freedom of blissful ignorance. A tradeoff between both worlds occurs, where life is learned to be cherished for what once was, and endless possibilities are taken with more severity.

57. The Killing

It only took two films for Stanley Kubrick to figure out what kind of a filmmaker he wanted to be, and The Killing was the turning point that really sits by itself in his filmography. Not as gorgeous and poetic as Paths of Glory (which would follow), but much more textured than anything that came before it for Kubrick, this attempt at straight up noir is still chilling to the bone. Shot well enough to be signature Kubrick, The Killing feels like a late response to a genre that had figured it all out already; it still wasn’t made quite like this. The criminal plot that drives this film becomes fascinatingly complicated, and all of the separate parts begin to send you into a pit of insanity at once. Even in a straight forward genre film, Kubrick knew exactly what could captivate audiences.

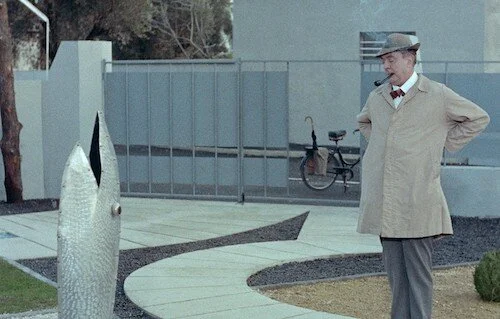

56. Mon Oncle

Jacques Tati was always France’s answer to Charlie Chaplin: a comedic director, producer, writer, actor and perfectionist. While his crowning achievement is Playtime, seeing how he got there is always interesting. Mon Oncle was the bridge between his fun satires and his untouchable comedy zenith. It’s stunning enough to make you step backwards and wonder how such a goofy film could be this beautiful (particularly the super-house at the heart of the entire film, named Villa Arpel, where most of the story takes place conveniently). Even this early on, visual gags were side splitting hilarious and breathtaking: a strange cocktail, indeed. With this sublime tester, Tati was ready to go one step further.

55. A Face in the Crowd

Maybe Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd didn’t do well upon release, because some of the greatest satires know more than the general populace at any given moment; Network was deemed an unlikely comedy at first. Now that we’ve seen the story at the core of A Face in the Crowd happen in real time, it’s a frightening depiction of the dishonesty of the media, and how the irresponsible transform from the latest story into the ruler of all. Turning Andy Griffith into a megastar of the screen (of all sizes), this acting debut feels like he was always meant to be on camera; there are no signs of amateur nerves here. Even at its lightest, A Face in the Crowd is hardly optimistic; rather, it is aware of its own demonic creations, knowing that they can be ignored but will never disappear (as long as society is easily swayed).

54. Cairo Station

Possibly the greatest Egyptian film, Youssef Chahine’s psychological noir Cairo Station is extremely progressive, particularly in its use of shedding light on problematic male behaviours. In away, the film frames the misdeeds of Qinawi sympathetically, almost in the form of an unreliable narrator. At the same time, Cairo Station knows better, and is using this opportunity to only compliment the toxic mentalities he carries with a tone that clashes against his desires. That doesn’t prevent Cairo Station from getting grim, which it does willingly in the name of telling a proper perspective. Neglected upon release, Cairo Station is rightfully adored now, likely because its preference of statement over narrative has beaten the test of time.

53. Othello

Orson Welles was already on top of the world in the ‘40s, and he was further exploring the noir genre at any given opportunity (even into the ‘60s). The ‘50s allowed him to begin his next big obsession: Shakespeare. While the unfortunate previous practice of performing Othello in blackface — committed by many — was standard and evident here, Welles seems to at least attempt to treat the role with the utmost consideration and respect. Otherwise, his Othello is an adaptation that focuses on the spirit that lingers amidst the words of Shakespeare, allowing shadows and imagery to become the major players of this romantic melodrama. As a work of Shakespeare in film, Welles’ Othello is one of the finest examples. As an adaptation that was true to the source (and not a creative deviation like Throne of Blood), it might be the greatest.

52. High Noon

One of the biggest Academy Award upsets is when High Noon was rallied against for blacklisting nonsensical reasons, and this turning point in the western genre went home with fewer Oscars than it deserved. A western drama that runs in real time (it doesn’t leap ahead or flash back in time ever), Fred Zinnemann’s classic is the battle against the clock, hoping every second will last a little longer before the duel of the decade. Because Zinnemann was willing to showcase the issues with the more self centred westerns that ruled before, John Wayne naturally got into a tantrum and called the film “Un-American”. Even with the laws of time, High Noon isn’t concerned with blueprints, and it’s a damn good reason as to why it continues to reign as a western staple.

51. Pyaasa

One of cinema’s finest romances comes in the form of the peak Bollywood film Pyaasa: a musical quest for the meaning of true love. This was Guru Dutt’s passion project, as he directed, produced, and starred in this magical journey through a symbolic heart found in the real world. Dutt uses his character’s vocation as a poet as justification to dive deeper into dream sequences or altered realities during musical numbers, which are obviously tropes of Bollywood; here, however, Dutt’s vision is unrivalled. A passionate epic that transcends many labels and remains a ‘50s classic, Pyaasa is proof that love forever conquers.

50. In a Lonely Place

1950 marked the start of a brand new decade, yet that didn’t stop noir experts Nicholas Ray and Humphrey Bogart from carrying out some of the finer moments of the ‘40s into this age. In a Lonely Place felt like a final word on the subject, as if Ray and Bogart knew the end of the classic noir was around the corner. In the same way that the characters in this film are all driven by guilt and a lack of trust, Ray couldn’t have complete confidence in the genre withstanding the test of time. So, he pulls out all of the stops here, with Bogart delivering his finest noir performance (as a suffering screenwriter, in pseudo meta fashion), and In a Lonely Place’s enthusiasm to ride out the most dismal of human emotions.

49. The Earrings of Madame de…

The wit of the title The Earrings of Madame de… is that we don’t find out this particular socialite’s name, but that this kind of story could pertain to anyone of extreme wealth. Max Ophüls follows the domino effect of one opening action, and sees fortune, greed, envy, and reward cycle around life, like a chemical reaction taking its course. Resembling a parable of sorts, The Earrings of Madame de… is an unpredictable chain of decisions that offset outcomes, as we are a ghostly viewer following these earrings around in anticipation of where they will end up next. Instead of seeing one character’s life, we experience many in a tapestry of circumstance.

48. All That Heaven Allows

It’s the autumn season in Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows, and winter is quickly approaching. Life is also sprinting once you get older, and this is precisely why Cary chooses to follow her heart. Unfortunately, the film can frame her blossoming romance with her hired arborist in Technicolor splendour only so much, since the rest of the world forbids her decisions. Sirk’s dilemma romance is incredibly warm when it is only full of heart, but it reminds us that life can get unforgiving or cruel in an instance. When winter hits, you have to live through it to see spring again. Some things are just out of our control, and our decisions are sadly irreversible.

47. Anatomy of a Murder

What I love most about Otto Preminger’s legal masterpiece is how quickly it demands to get into the nitty gritty. We get a backstory set up for a little while, and then it’s courtroom business for the majority of the picture. As a result, Anatomy of a Murder is a triumphant success in the genre, containing some of cinema’s strongest legal battling of all time. You cling onto every word of each side, wondering where this mysterious case is going to go. Even then, the film’s twists (particularly its largest) can’t be seen coming, and all of these curveballs only make the trial all the more juicy; the biggest tossed wrench destroys the entire machine in exhilarating fashion.

46. The Hidden Fortress

Known as the film that basically inspired most of Star Wars (specifically A New Hope), Akira Kurosawa’s spiritual samurai epic The Hidden Fortress is the kind of blueprint only the best films could pull from. You can see where George Lucas got all of his inspiration from. Even amidst Kurosawa’s finest samurai films in his golden age, The Hidden Fortress possesses its own magic, perhaps in the whimsical music or the haunting cinematography. While other Kurosawa greats feel like lessons, debates or fables, The Hidden Fortress is specifically a journey. It invites you to go deeper into an illusionary landscape and within the political overhaul of war.

45. Ashes and Diamonds

After World War II, many saw this as a sign of a brighter future, now that this harrowing moment in history was over. Not Andrzej Wajda, who found Jerzy Andrzejewski’s Ashes and Diamonds and had to share this discovery with the world. The evils of humanity are within all of humanity, so this picture’s depiction of faltering sides collapsing on one another encompasses all of that. Granted, maybe Wajda and company got carried away with their storytelling and created some embellishments, so Ashes and Diamonds may not be the strongest history lesson it was made out to be initially. As a discussion on morality, however, Ashes and Diamonds is frightening cinema.

44. Sabrina

I wouldn’t dare call Sabrina overlooked (it did get remade, after all), but it does feel like the Billy Wilder film that is discussed in smaller circles (like the whispering gossip that surrounds Sabrina Fairchild herself). Almost a full on romantic comedy, Sabrina feels like the last dregs of Wilder’s noir era, so portions of the film are rather grim (these scenes are only overcome by charm, of course). More interested in the magic of the moonlight than the beating of one's heart, Sabrina feels like the essence of falling in love and not knowing where this will lead. Especially with two noir Hollywood heavyweights — Bogart and Holden — competing head-to-head, Sabrina is the sensation of finding adoration in the least expected places.

43. Sansho the Bailiff

Kenji Mizoguchi was always fascinated with turning lore into hyper real cinema, that was tangible in every sequence. Sansho the Bailiff is a retelling of a Japanese folk story, but conveyed with a neorealist lens to heighten the severity of the tragedy on screen. Following a shattered family, as two children are stolen from their mother and sold into slavery, Sansho the Bailiff is the pursuit of hope amidst the darkest moments in one’s life. A difficult film full of massive triumph, it feels impossible to finish without shedding at least a couple of runaway tears. Mizoguchi didn’t just recreate lore: he helped shape cinema permanently.

42. Imitation of Life

Something about the works of Douglas Sirk becomes too overbearing to take in all at once, and that’s evident in the heartbreaking melodrama Imitation of Life. A family is imploding because of revelation, and society’s brainwashing ways have instilled racism, sexism, and classism in the minds of the next generation. With both factors together, we have the shunning of loved ones because civilization told us this is right. Nothing is more honest than the connection with those that mean the world to you, and Sirk wasn’t afraid to test the limits of that statement. Imitation of Life knows how to celebrate time well spent, but it never forgets how devastating it is to lose that negligently as well.

41. The Human Condition

So, this entry is a bit unique, given that The Human Condition is technically a trilogy. However, considering how all three parts are connected as one whole (technically six chapters in total), and the third part (A Soldier’s Prayer) was only released in 1961, I felt that the easiest way to go about this was to include it all as one film, as Masaki Kobayashi intended. For nearly ten hours, we follow Kaji as he takes on almost every single hardship known to humanity as a prisoner of war (in many different ways, including symbolically). To watch The Human Condition is to understand one of cinema’s strongest tests of strength. It’s only natural that you experience it in its entirely.

40. Journey to Italy

When Hollywood was still cramming in as many everlasting romances on screen as possible, Roberto Rossellini was ready for something real. Journey to Italy pits together two spouses that are immensely out of love (played by Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders) and sees how many uncomfortable situations they can suffer together. Even when it is “resolved”, there is an obvious gap between the wife and husband: the noticeable kind that not even a hokey Hollywood bow could pretend is nonexistent. Especially now, Journey to Italy feels more in line with the bittersweet romantic dramas of the new millennium than when it was released, because it refused to sugar coat the real kinds of lethargy that many couples experience. With Rossellini’s excuse to show a bit of Italy (as he usually did), Journey to Italy is as exquisite as it is crushing.

39. North by Northwest

Alfred Hitchcock liked to have fun in some of his films, and he had genre-chameleons like Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint in North by Northwest to work with. This is one of his more playful thrillers, with so many jokes and bags of charm at every corner. However, the film still accepts any form of danger, and gets legitimately concerning in this cat-and-mouse chase involving mistaken identity. North by Northwest doesn’t know how to quit either, sprinting at full speed right until the very last cut: a jump cut that catches absolutely every viewer off guard. Who knew that being lighter could be so daring?

38. Summer with Monika

The very first film to put Ingmar Bergman on any sort of wide scaled map was his existential getaway drama Summer with Monika. It felt like a cry out for help to escape the film industry, critical pundits, the duties of society, religion, and Sweden as a whole. The plan to escape the world and live independently in a private location doesn’t go according to plan, and both young partners here — including Monika herself — are full of their own secret desires. Life doesn’t come easily to most, mainly because our own personal definitions differ from everyone else. Summer with Monika is a lifetime of wondering where it all went. The joys in life just zip past, and we’re left with questions we can’t answer.

37. Sweet Smell of Success

Films noir and motion pictures about journalism are both extremely literary, given their penchant to rely on textured dialogue, settings that are aesthetically descriptive of moods, and tensions rising over fabrications and lies. So, Sweet Smell of Success truly is the successful concoction of both worlds, as a young hot shot (Tony Curtis) is picked up by a veteran of the field (Burt Lancaster) to cause some chaos. The film is so visually dark, you cling onto every single word as if it were the last glimpse of natural light remaining. This works, given the amount of red herrings, circlings-around, and revelations that are delivered in half truths. By this point, films noir were basically finished, and a film this spectacular was certainly one of the final says.

36. Limelight

Talking pictures came, and Charlie Chaplin relented against them with additional silent (or mostly silent) films. He eventually gave in, but remained daring with The Great Dictator. By the ‘50s, Chaplin had been there and done it all. So, Limelight was like a definitive final statement by Chaplin (although it wasn’t actually his swan song). Featuring an artist on his way out trying to save the life of a new talent refusing to go on, Limelight feels like the passing of the torch to a rising generation. Still as lovely and funny as ever — even with full on dialogue — Chaplin dazzles in this bittersweet love letter to performing out of love. All things considered, Limelight is imperative Charlie Chaplin viewing.

35. Marty

Marty is just one of those films that seems to work with almost anyone that watches it. A Palme d’Or winner and a Best Picture Oscar winner, it feels like it won with both art circles and the masses. It’s peculiar, because the film is progressively dismal for its time, honing in on the difficulties of the titular butcher and his lonely, miserable life. As forward-thinking as director Delbert Mann was, this feels like writer Paddy Chayefsky’s child from scene one, as each line of dialogue is a bold statement that narrowly passes the Hollywood Code with how pessimistic they are. Sometimes, the biggest wins are the smallest changes in life, and that’s all it takes in Marty; your heart will be won over more here than some of the most ambitious epics.

34. Ugetsu

The new wave of Japanese films that was on its way can be linked to many of the ‘50s greatest storytellers like Kurosawa and Ozu, but one of the major starting points was Kenji Mizoguchi’s gorgeous ghost tale Ugetsu. So clouded by fog and the civil war, Ugetsu reels you in simply through its mysteriousness. Usually, you can judge a character’s actions from a distance, since you’re sitting comfortably away from what you’re seeing. Not here. Ugetsu is so hypnotizing in its beauty, you’re guaranteed to wander around aimlessly within the film yourself. Ugetsu paved the way for Japanese cinema for years to come (as a great example as “kaidan”, or a spin on the style), as its popularity was clear evidence that the world needed to get in touch with films as poetic and culturally exquisite as this one.

33. Aparajito

Satyajit Ray’s second Apu film, Aparajito, is one of the finest bridge films in any trilogy. Sure, it does the trick with connecting Panther Panchali and Apur Sansar, but it is still a fully functional film with its own important themes individually. Apu has to learn how to become a provider, and thus has to become educated. He discovers himself in his studies, emotionally distancing himself from his family back home. Ray places us in a difficult situation, where there is no proper answer: do we continue to strengthen ourselves, or do we take a step back and give it all up for the difficulties we’ve faced until this very point? For a film that’s the middle section of a triptych, Aparajito is still perfect storytelling.

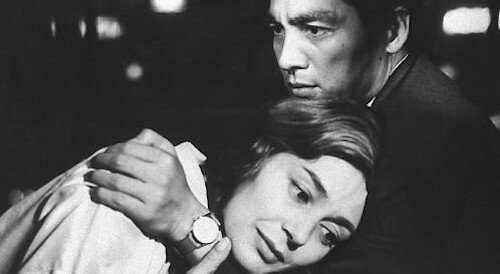

32. Hiroshima mon amour

Before Alain Resnais got fully engulfed by the complexities of memory in Last Year at Marienbad, he toyed around with the idea in a borderline docufiction fashion with his sterling debut Hiroshima mon amour. Telling the recounts of a romantic couple surrounding the horrors of war, the film is stuffed with footage and dream sequences, amidst the discussions of lovers who view the same horrors in their own differing ways. The film barely even eases you into its fragmented nature, as you’re tossed into the deep end to fend for yourself amidst narration and isolated moving images. Resnais discovered how to replicate memories on film before he really began to screw around with the idea, but he managed to do so very quickly in his career.

31. Touch of Evil

It’s only natural that the director of excellent classic noir films was one of the last to say goodbye to the genre in style. Touch of Evil has become a FILM 101 staple because of the harrowing production stories surrounding Orson Welles and his troubled project, but the end result is still exhilarating. Starting with a long take that ends in a literal bomb going off, you’re left tiptoeing around the rest of the film, awaiting any danger that is going to pounce on you. Without ever letting up, Touch of Evil only digs deeper and deeper into the depths of the human soul, exposing just how ugly we can all get as creatures of habit. Notorious and celebrated, Touch of Evil is a brilliant film created by relentless, acidic perfectionism (amongst other things).

30. A Man Escaped

Usually, Robert Bresson’s attention to detail in his films came from his knack for storytelling in a way that every little event can become a must-see spectacle. In A Man Escaped, things got personal. Bresson was a member of the French Resistance, who was locked away in isolation, much like André Devigny, whose prison escape is the basis for A Man Escaped. As meticulous as The Great Escape, but shot with a realistic lens, Bresson’s film places you right in the middle of these plans and the actual attempts. In a way, A Man Escaped resembles the kinds of thoughts Bresson may have had when he was locked away from the rest of the world, as the titular person and their achievement remains Bresson’s most triumphant moment.

29. Ballad of a Soldier

Russian cinema was entering a new age in the ‘50s (a prime example is placed higher on this list), as if the Russian way of telling stories was being challenged like it was when the art of film was first being figured out. Ballad of a Soldier is told almost entirely poetically, with every single image serving as its own story of a thousand words. We are given the opportunities to cherish every moment, because the soldiers in Grigori Chukhrai’s film don’t have that opportunity. This quest to return home at any cost is obviously burdened with many obstacles, including what seems like the pursuance of individuality itself (which gets in the way of the return). This film could be about any soldier that is removed from the lives they fight to protect.

28. All About Eve

For us, this almost felt like the death of the screwball genre. All About Eve has all of the biting dialogue and retorts of the departed style, but it shed off any of the inherent silliness that was formerly a must-have. It’s the removal of a safety blanket: you can’t rely on goofiness to save the day when the story gets dicey. All About Eve is about real dramas and real moves, including the usurping of your idol in order to become the next legend, even for a little while. Suddenly, funny responses turn into sarcastic sneers and jabs coated in acid. If All About Eve wasn’t the cause of the end of screwballs, it was at least an excellent argument that comedy dramas (or dramas with comedic elements) could be so much more.

27. Elevator to the Gallows

Crime obviously comes with ripple effects, no matter what the deed is. Elevator to the Gallows is a Rube Goldberg machine of the actions that transpire after a murder — done with “good” intentions — takes place. With Miles Davis’ runaway score, the entire fate of the film feels unpredictable and unsure from the get go. So, we just follow along for the ride, and see where Louis Malle’s classic takes us. Neither explicitly a noir film or a new wave staple, Elevator to the Gallows kind of exists in its own little world, which is part of the film’s long lasting — and ever growing — legacy; the other reason is how anxious the film can be for all eighty eight minutes.

26. Ordet

One of film’s strongest takes on the discussion of religion and personal beliefs is Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Ordet, where three sons in one family have completely different faiths. Domestic life has become the clashing of different ideas, which is already an interesting experiment. However, like he always tended to do, Dreyer vowed to go even further with this story, by implementing God complexes and complete damnation to these characters. The way Ordet is shot is as if we’re not even on Earth at all, but rather in a purgatory, seeing lost souls figure out their own fates as to leave this timeless, lifeless void.

25. Les Diaboliques

Alfred Hitchcock made a number of the great ‘50s thrillers, but Les Diaboliques wasn’t one of them; it ended up being the film that got away for the director, who in turn made Psycho as a response (not much of a loss there). Instead, we have Henri-Georges Clouzot’s incredibly haunted version, which does carry a different feel than what we may have gotten. The crime plot is already an absolute feast, as we see two women hurt by the same man scheme his death. Plagued by these wrongdoings, both leads in Les Diaboliques both seemingly go crazy for the duration of the film. Then, there’s the twist of twists, which is unparalleled in all of film; it’s as shocking visually as it is conceptually.

24. Rashomon

Many filmmakers have tried to recapture what Akira Kurosawa achieved in Rashomon, which has led to the type of storytelling known as the “Rashomon effect”. Let’s be honest: no film is pulling off the different recounts of unreliable narrators the same way that Rashomon has. Placing a misdeed at the centre of the film is one thing, but using the evils and unfaithfulness of humans as the means to skew these alibis is just genius. The punctuation point is how we keep getting chewed up and spat back out to the present in the film, only to be left wondering even more about what really happened; usually films have more resolution as they go on after a certain point, and we now have to wrestle with uncertainty. It’s this kind of bold filmmaking that set Kurosawa heads and shoulders above the rest of his peers.

23. La Strada

Even though Federico Fellini would later explore vignettes and stream-of-consciousness styles of filmmaking, his ‘50s dramas are excellent in their own right. This includes the heavy hitting La strada, where we follow Fellini’s muse Giulietta Masina’s Gelsomina through an entire life of turmoil. Gelsomina is forced to be a circus entertainer against her will, and is even heavily abused by her husband who she had no say in marrying (who is also a part of the same circus). Like a simile of living in lower class Italy, La strada is a late answer to Italian neorealism. Earlier Fellini works contained a fight in them, when he was still rising as a voice in his field. La strada was an early sign that he was heading in the right direction.

22. Rear Window

It’s safe to say that Alfred Hitchcock tried something new with every single film that he ever made, but the greatest experiment he ever concocted is Rear Window: a motion picture confined by diegetic blockades. For example, all of the sound comes from within the film’s contextual setting; even the “score” is played by a neighbouring pianist. As for the mystery, we are stuck from one single vantage point the entire film, and we have to rely on whatever the film gives us as evidence. Even with usual Hitchcock players like Jimmy Stewart and Grace Kelly, Rear Window is so singular that its premise supersedes any other reason to watch the film (although every person and element of the film operates at a top level). Debating what Hitchcock’s magnum opus is is difficult, I know. I can definitely say that Rear Window is easily his most interesting risk, though.

21. Pickpocket

You can look at someone like Robert Bresson and just know that they can turn anything into cinematic art. How can the act of robbing someone look so eloquent and fascinating? Well, in the ways that Riefenstahl captured sports or Vertov shot every day life, Bresson just knew how to film thievery in Pickpocket; it’s as if we’re watching a magician create illusions before our very eyes. Even just the sequences of Michel learning how to properly steal objects is masterful filmmaking that you cannot ignore. Toss in Bresson’s depictions of letting life slip away when we’re fixated on the wrong things, and you have a French cinema fable that only gets more beautiful with time.

20. 12 Angry Men

Of all of the versions of Reginald Rose’s Twelve Angry Men, Sidney Lumet’s directorial debut is by far the greatest. Somehow, he manages to keep all of the discussions and debates enticing for the entire film, despite being stuck in one room for one massive scene for most of the runtime. Truly capturing that fly-on-the-wall feeling that many of us wish we had in these kinds of situations, 12 Angry Men is pure adrenaline, surrounding the fate of someone who doesn’t even have a say in the matter. One of the courtroom genre’s finest moments, Lumet’s rendition was a jumpstart to his own career, as he single handedly refined what the legal system could be like on screen: complete pandemonium.

19. Los Olvidados

It was considerably risky to have made a film more about circumstance and setting than plot back in the early 1950’s, but Luis Buñuel — at a major turning point in his career — opted to do so anyway with Los Olvidados. The bottling up of all of the griefs of life in the ghettos of Mexico City, Los Olvidados feels like a purgatory for many youths that were doomed from the seconds they were all born. As we are all very aware by now, Buñuel was always a fighter for working and lower classes, but this ‘50s neorealist drama of his is some of his most straightforward commentary that he ever made. For a surrealist, satirical genius to want to get this upfront is serious; thus, every hit in Los Olvidados lands.

18. Seven Samurai

It’s impossible to forget what is quite possibly the definitive war film in terms of how the genre was redefined; action in cinema was forever changed as well. Once Akira Kurosawa was firing on all cylinders, he was ready to make something as ambitious as Seven Samurai. The slow burning opening act (the assembly of said samurai) leads into the more calculated second portion, only to ride up to the lengthy, explosive climax; all of this leads to the most bittersweet final line in film. The ways Kurosawa choreographed combat in Seven Samurai have been copied throughout history, only for most attempts to fall short. Hell, even every The Magnificent Seven remake of this film feels futile.

17. The Searchers

Even Clint Eastwood fans have had to swallow their pride and accept that one John Wayne feature was worth this much of a damn, and that masterpiece is The Searchers. The greatest duet between the western icon and filmmaker extraordinaire John Ford, The Searchers aimed to be the very best classic western that there ever was, succeeding on all fronts. Using the wastelands during all seasons as the primary setting, Ford’s direction has never been this gorgeous. Trying to better understand the conflicts between the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and the Anglo-American settlers also allows The Searchers to age better than some of its contemporaries, as it dips into a grey area that’s up for debate; Ford's opus effectively put an end to the classic western hero, using the face that was most attached to it.

16. On the Waterfront

In 1954, one single film managed to change so much about Hollywood filmmaking. Elia Kazan’s blistering On the Waterfront devoted so much of its story to the aftermath of a budding boxing career, leaving us in the shadow of promise. Marlon Brando’s medium defining performance made a portion of acting take place on the stage inside of a character’s mind. Leonard Bernstein’s score ushered in a new age of composition for the screen, reacting more with feeling as opposed to mimicking what characters were doing on screen. In almost every way, On the Waterfront’s underdog story wasn’t very underdog like at all; if anything, this was all about trailblazing through the blueprints of cinema, to the point that it became the archetype itself.

15. Umberto D

Unlike some of his peers, Vittorio De Sica didn't always vow to create realistic films that wallowed in depression. However, when he aimed to do so, he was one of the very best at depicting sadness on screen; Exhibit A is Umberto D, which is an incredibly difficult film to view without tearing up. Following an abandoned man who has been thrown out of his home, and his best friend in the world (his pet dog), Umberto D is a never ending fight against the world that only seems to get more and more somber. By its third act, De Sica’s film becomes the ultimate quest to keep going, even during one's darkest hours. It’s a reevaluation of life that is as triumphant as it is heartbreaking.

14. The Bridge on the River Kwai

David Lean’s Best Picture winner The Bridge on the River Kwai takes so long to gradually make its case: the titular bridge is slowly built, with much reluctance. Some characters on either side — British prisoners of war and their Japanese captors — begin to mesh after much disagreement. Other characters begin to fulfill their own plans. Much chaos is going on circling this one mission to complete the bridge. Then, the final act has every single plot thread colliding. Even still, to have three hours of build up is one thing. Making the major turning point happen right after everything is the kind of madness that only an epic like The Bridge on the River Kwai can fulfill, rendering this war drama timeless.

13. Pather Panchali

At the start of Satyajit Ray’s perfect trilogy was the hypothesis, in the form of Panther Panchali. We follow a young Apu and his struggling family that try to get by in any way, shape or form; optimism certainly helps. On its own, this is Ray’s answer to neorealism, and a sign that the iconic director was made to tell stories of his motherland. Panther Panchali is touching, but also incredibly hopeful. In the Apu Trilogy, this first entry is even better, knowing what comes afterwards in Apu’s life (both the accomplishments and the hardships). This is the opening statement that allowed Ray to keep going, despite the funding woes that initially held him back. While both other Apu parts are narratively nuanced, Panther Panchali feels like it exists in its own realm, tethered by nothing in its depiction of life of all sorts as poetry.

12. The 400 Blows

While the '50s contained a number of works that helped shape the upcoming French New Wave movement, François Truffaut’s debut classic The 400 Blows felt like the definitive start to the movement, clear as day. It certainly is easy to label the film as such, given its graceful depiction of youthful mischief in a way that called back to the cinema of attractions, where capturing anything on film was something to behold. When Antoine skips class to explore the town, we see a difficult child mature. Society gets the best of him and delivers his comeuppance for his lies and troublesome behaviour, it's as if we're seeing someone being held back, mainly because of their own doings of course. We freeze on a single glance with eternity reflecting in Antoine’s eyes, unsure of whether or not he will be okay, stripped away from civilization’s clutches. Cinema was in a similar spot. Seeing that The 400 Blows is still perfect sixty years later, it seems like veering off course is sometimes worth it.

11. Paths of Glory

If The Killing was Stanley Kubrick's way of confirming that he was meant to be making motion pictures, then Paths of Glory was the exact moment that he became a cinematic legend for years to come. Contrary to the epics he would soon be known for, Kubrick worked succinctly with Paths of Glory, containing entire lifetimes of sorrow and pain in less than an hour and a half. Should soldiers take part in a suicide mission? Is it anti-American to refuse to knowingly die for your country in large masses? Kubrick’s anti-war film dared to get real during a decade where fear dictated much cinematic output; that didn't stop him from conjuring up a gorgeously devastating finale that remains one of his greatest achievements.

10. Nights of Cabiria

Federico Fellini was now established as a fantastic auteur that was bringing life to cinema that was never felt before. Before he could get experimental with this new found ability, he had to perfect his dramatic chops. After the success of La Strada, Fellini teamed up with starlet Giulietta Masina to make a spiritual successor called Nights of Cabiria. The titular Cabiria’s life continues to get worse and worse, and Fellini dips towards dark territory he rarely revisited since; it was as if he discovered that this was the best he could get with tragedy. To be fair, Nights of Cabiria is truly one of the great tragedies of the ‘50s, which all encapsulated the hardships of the lower classes that many faced for decades up to that point (and sadly afterwards).

9. The Night of the Hunter

I see some connections between Citizen Kane and The Night of the Hunter, mainly the harsh response upon release which has since been reevaluated. However, Orson Welles was transitioning from stage to screen and never gave up (he also was still nominated for many awards). Charles Laughton was an established actor wanting to now direct pictures, and he sadly gave up after this debut. We’ll never know what could have come next, given Laughton’s spooky visuals, incredible imagination for shot and sequence compositions, and vicious content that preceded the end of the Hollywood Code perhaps too early. With all of those that were influenced by The Night of the Hunter for decades to come, those are the best indications that we have. It's still sad, because Laughton managed to make a gorgeously horrific film for the ages on his first try.

8. Singin’ in the Rain

Between the colourful Stanley Donen and the perfectionist Gene Kelly, at least one feature they would collaborate on would have to be good. Well, Singin’ in the Rain is beyond good. It is, without question (for us, at least), the musical of musicals, the most joyful production, and a contender for best-of lists of all sorts (including my own). Musically alone, Singin’ in the Rain reimagines classic songs as its own, giving new life in a way that has rendered these standards as this film's own. Then, there is the commentary on the transitional period between silent films and talkies, told with highs, lows, and everything in between. The romance at the heart of this film is so warm, too. Have all of these components collide at the end, and you have a film that's sure to cure any sadness you previously had (even for a little while).

7. Rififi

Many films noir operate with talking and deceptions. Rififi loved working in silence, including the robbery sequence that takes place with nothing but the noises of the job for around a half hour. Jules Dassin fled the United States during the blacklisting era and landed in France, only to find that he could truly explore what he wanted to do over there much more easily. As a result, he adapted Auguste Le Breton’s Rififi his own way, and single handedly created one of the best noir films of both Hollywood and France (an incredible achievement, for sure). Easily one of the more artistic films in the genre, Rififi is so forward thinking, as if made purely out of spite and stifled creativity.

6. The Seventh Seal

Ingmar Bergman has experienced many turning points in his career, but the only one of his that matched the course of film itself explicitly upon release was The Seventh Seal. Clearly a significant film amongst the works of world cinema that were egging Hollywood on to keep up, Bergman’s medieval existential drama felt more like Bergman finding himself, trying to figure out his religious beliefs once and for all by airing out all of his baffling questions he's carried for years. Instead, Bergman created a movement there and then, where the art of the world had a place in cinema, and religion wasn’t off the table when it came to what films could discuss. Beautifully cursed and bittersweet on all fronts, The Seventh Seal was the specific moment that Bergman had finally made it big, and arthouse cinema was entering a new chapter.

5. Ikiru

Even in a decade where Akira Kurosawa’s period pieces — mostly samurai tales of sorts — dominated, the work of his that comes out on top is the then-contemporary story of rebirth through legacy after death. Ikiru is such a touching drama about the discovery of life's worth even in one's final seconds alive. Instead of a lone fighter taking on an entire army, Kanji Watanabe is a dying citizen trying to change the outlook of those that feel like they have all the time in the world left. Ikiru is a call for societal reform: to focus on the things that make civilization’s inhabitants happier and enriched, not what makes us richer. Not much about the world's mundane practices gets solved in Ikiru, but Watanabe’s personal mission becomes a piece of all of us after we’re done watching.

4. Sunset Boulevard

It takes a lot to be Billy Wilder's magnum opus, but Sunset Boulevard is easily the holder of that title no matter what. If Singin’ in the Rain was a celebration for the silent stars that made it into talkies, then Sunset Boulevard was a tribute to those that vanished. A touching homage to cinema, Wilder’s strongest triumph still has a lot to say about the hidden secrets of an industry that pretends to be full of glitz and glamour: an obvious truth now, but more of a necessity to be told in 1950. Tossing in a twisted romance and cold blooded murder, all in the name of delusional fame, Sunset Boulevard carries on one final honour: being the greatest black-and-white noir there ever was.

3. The Cranes are Flying

Mikhail Kalatozov clearly was ahead of his time. With I Am Cuba, he was clearly making ‘60s arthouse pictures. Only seven years before that, The Cranes are Flying was a window that looked in to what the future of arthouse was going to look like, with an anti-war masterpiece that rode entirely with emotions. Tethered by the feeling of guilt (Veronika is forced by men to take on many roles she didn't sign up for during wartime, only for the world around her to seemingly chastise her), The Cranes are Flying is a nonstop roller coaster of emotions, paired up with some of the most exquisite images and compositions of the ‘50s. By the time the picture wraps up, you’ll know that Kalatozov knew that films would be driven by overwhelming aesthetic beauty soon enough.

2. Vertigo

The love for Alfred Hitchcock’s opus Vertigo has only gotten stronger over the years, perhaps because it has had a chance to shine amidst all of his other stellar pictures. Ironically, the best film noir ever is in dreamy Technicolor, where hues are purposefully used to toy with the viewer. Then, there's everything else: dolly zooms to mimic the titular vertigo, animation to lead us into a dream sequence, and spirals in hairstyles, wardrobes, and props. Hitchcock was forever trying something new, but Vertigo was one such case where all of his many ideas all came into place seamlessly. The master of pulling the rug from underneath his audience, Vertigo is impossible to figure out right up to the last, unforgiving second. That’s Vertigo’s longevity: how much we love the many ways it has messed with us on every single viewing.

1. Tokyo Story