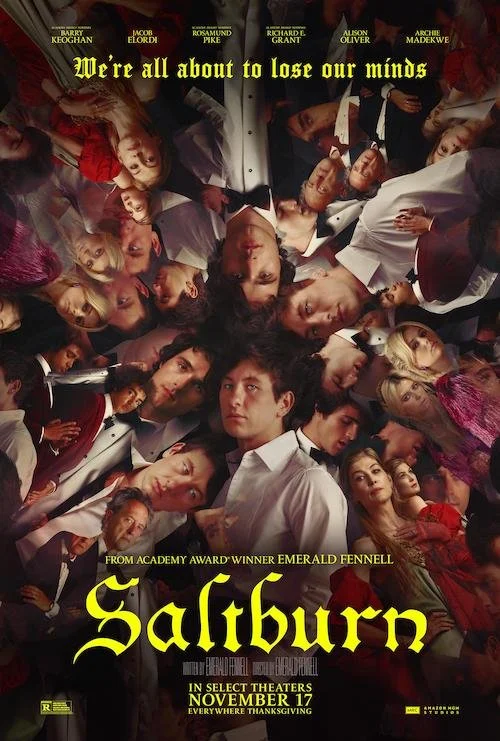

Saltburn

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Star-turned-director Emerald Fennell made quite a splash in 2020 with her feature film debut Promising Young Woman: a self-aware, feisty-yet-fascinating dark comedy thriller with poignant, sharp social commentary on misogyny and toxic masculinity. She was nominated for several major Academy Awards and ultimately won Best Original Screenplay for her ability to craft silly-yet-witty dialogue, jaw-dropping turns, and some major shocking twists (including the biggest reveal which happens far earlier than anyone would have ever expected). I viewed the film as quite a strong release but just the tip of the iceberg as to where Fennell could go from there: not to be lazy with my usage of words, but promising was most certainly the first term that came to mind for me. Promising Young Woman was the starting point. So what came next? We have arrived at Saltburn: both a worthy successor and a bit of a step backward for a director who ultimately knew the sky was the limit for her and aimed to go all-out in a coveted follow-up.

I suppose the main thing that left me scratching my head is how right everyone has been with the comparisons to The Talented Mr. Ripley, and a direct or loose adaptation isn’t exactly a problem. I think we were all expecting something a little more original from a new filmmaker who already showcased her imagination before. At least Saltburn is different enough and Fennell’s thumbprint is all over it. We start with the talented Oliver Quickley (excuse me… Oliver Quick) who is seen as a desperate, impoverished colleague by other students at Oxford University; Oliver is there via scholarship and it is implied that he doesn’t come from wealth. Felix Catton is a fellow student who does come from a rich family and he quickly comes to Oliver’s side. After they develop a friendship (and what seems to be something more), Felix seeks to comfort Oliver after the latter’s father passes away from an addiction-related cause. They reach Felix’s family estate: Saltburn, where Oliver meets the rest of the Cattons, cousins and all.

What starts as a blossoming opportunity for Oliver to thrive (and for his relationship with Felix to take off) becomes a game of psychological warfare, and Fennell’s biggest influence not written by Patricia Highsmith gets revealed: Bong Joon-ho’s masterpiece Parasite. Yes, Oliver is invited by some of the Catton family to make himself at home in Saltburn (outside of maybe cousin Farleigh, who is weary of Oliver from the getgo), but Saltburn ultimately is a test as to how “at home” Oliver chooses to be. Without getting too deeply into it and spoiling the major twists of the film, Saltburn is yet another eat-the-rich satire at heart, but this time there’s perhaps a little bit of sympathy for the aforementioned wealthy who get decimated via this genre’s conventions: Fennell seems to comment on the hideousness of opportunists and how this is as unethical as the snobbishness and arrogance of the elite.

I don’t think this talking point is entirely off-limits despite how apologetic it may seem to some, and I think this stance is at least an understandable one from Fennell who comes from wealth herself (her father is the Theo Fennell of the jewelry empire of the same name). At least Fennell tries to meet both parties somewhere in the middle: acknowledging that you don’t have to be a privileged jackass if you are fortunate (some of these characters are nicer than their cohorts), and there are just some ways not to work your way up the ladder of society. While Saltburn doesn’t really bring out the injustice of societal imbalance quite like, again, Parasite (or other likeminded films like The Menu or Triangle of Sadness), it does focus on the running high of fortune and the addiction one may have when experiencing a slice of easy living. Classism is inferred, and at least it is subtle when Fennell is such a maximalist filmmaker (not a sleight, by the way).

Saltburn may not achieve as much as Emerald Fennell aims to pull off, but it feels like a riskier film from the newer filmmaker with occasional, strong payoffs.

Saltburn is bolder than Promising Young Woman, and you can sense this quite quickly with how this film looks. If Promising Young Woman is a neon-coloured, suburban wonderland, then Saltburn is a lush fever dream that verges on being full-on hallucinatory (it certainly is one of the best-looking films of the year, and Fennell matches Linus Sandgren’s gorgeous cinematography with stylized storytelling, unorthodox characters, and other otherworldly elements that allow Saltburn to fully gestate into a psychedelic trip). While I wouldn’t claim that the twists are more clever than those in Promising Young Woman (nor can they necessarily be riskier than, again, the biggest twist in that film), Saltburn still plunges into its darker turns with very little warning with enough speed to elicit gasps from its audience; I hope Fennell doesn’t become the kind of director to heavily rely on twists to get by, but fortunately she so far doesn’t seem to be overstaying her welcome one bit.

Fennell’s kooky characters are best matched by some powerhouse performances that understand her sense of humour, her commentary, and her electrifying mind. Barry Keoghan somehow pulls off the impossible of playing someone over ten years younger than he actually is (then again, it’s Barry Keoghan: a brilliant actor who has dominated every film he has been in), playing Oliver as a master manipulator of naivety. He is paired up with Jacob Elordi as Felix, and it’s weird to proclaim that the actor is working against type here (he’s not playing an entitled jackass, despite being the heir of a rich, privileged family? Colour me surprised). His parents are a wonderfully oddball couple played by Rosamund Pike (as quirky Lady Elspeth) and Richard E. Grant (as the ticking time bomb Sir James), and even Promising Young Woman’s star Carey Mulligan pops in via a strange cameo as “Poor Dear” Pamela (friend of Lady Elspeth who I kind of wanted more of despite knowing there was nothing else she could have offered). The entire cast provides growth to Fennell’s writing and directing; her debut felt like a protagonist in a world that’s against her, whereas Saltburn does elevate the stakes via a lineup of characters who are so textured that they all could have had their own films given the opportunity).

While these kinds of moves felt like they paid off for Fennell, I cannot help but feel the eat-the-rich angle that Fennell was going for isn’t quite fully realized. Fennell settles for the seat at the proverbial table, whereas the other similar films of the genre keep going past this point (what does it mean to be at the table?). I understand Fennell’s point that if you don’t come from old money, chances are only awful people can get to this level of comfort at such a young age, but I also feel like we could have afforded just a little bit more. Saltburn is — without trying to make a pun — a slow-burning film that really picks up steam in its third act, and it is conducted quite nicely in this way; while I felt a bit restless at first and wondered where this film would go, I feel like the parade of payoffs justified the opening acts.

It is the final shot that, while magnificently composed, left me wanting more. I got the fleeting freedom and the celebration of a long-brewing plan coming to fruition, but is that really enough? Saltburn paints this finale as a triumph when it is better served as an ambiguous waltz between support and scorn. I also get that Saltburn is led by an unreliable narrator, so it is, for this reason, I can accept the final sequence for what it is (it helps to justify such a glorious close). Then again, I still want more; more to say in this discussion about opportunities between different classes; more on the lingering aftermaths of what transpires; more on whether or not remorse or guilt is ever experienced. Emerald Fennell utilizes some instances of subtlety in a film full of loudness proving that she is aware of how much of each ingredient to put into her casserole, but I do think Saltburn could have done with a bit more narrative salt; at least the dish wasn’t overcooked, let alone burned. With all of this in mind, I implore Fennell to not slow down with the craziness of her visions because I still think we have yet to see her at her most unhinged; she must also keep in mind the same fullness of story that Promising Young Woman delivered while she aims to go further and further with her black comedy phantasmagorias.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.