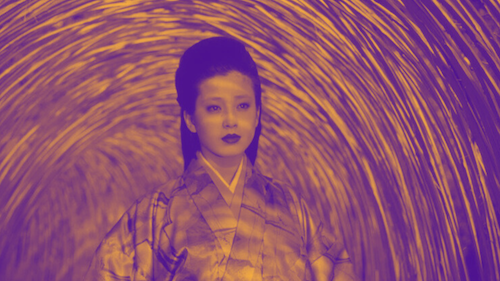

Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Hiroshi Teshigahara Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Directors

A few filmmakers can be considered your favourite director's favourite director, and such a label can be applied to the great Hiroshi Teshigahara. Known for his exemplary avant-garde films within the Japanese New Wave movement of the sixties, he was always able to find inventive ways to tell stories (or, in numerous cases, fables). He had such a keen eye for visual splendour, either with extreme close ups or the widest of shots. To watch a Teshigahara film is to experience film in a way you simply haven't before; even the many directors inspired by him haven't quite nailed the aesthetic poetry and stirring, haunting nature of his works. Yet, outside of a title or two, Teshigahara remains underrated and underdiscussed. Why is it that some of the most unique directors — those who explicitly stand out — wind up being overlooked? I know that he has a trio of adored titles, but I will preface this list by stating that I don't think he made a single bad feature film; all eight titles here are worthwhile to me. He wasn't a director who struck gold a couple of times: he was a consistent master.

Perhaps his elusive legacy stems from his many commitments. He released a number of short films (because of the difficulty of tracking down many of them, I simply won't include the shorts here), but his expertise existed outside of cinema as well; his affinity for installations and exhibitions — akin to the kind of artistry he was committing to celluloid — took up much of his career, from being the director of the Sogetsu Art Center for fifteen years (starting in 1958) to working on collections from the eighties onward. With this in mind, his aesthetic style makes sense: he has turned the concept of cinematic shots into a fluid, linear art gallery. Before film, my passion was art (of all kinds), and I have always chased after works that give off that stimulating provocation (a call-and-response between the artist and the observer). Not everything should be challenging, but all should at least mean something. With Teshigahara's films, I see purpose in every shot, every cut, and every word. Here are the feature films by Hiroshi Teshigahara ranked from worst to best.

8. Summer Soldiers

Placing anything last feels wrong, but one film has to take the fall. Despite its apparent popularity, Summer Soldiers has to be that sacrificial lamb for me. This anti-war film merges both the Japanese New Wave and New Hollywood movements within the backdrop of the Vietnam War, and Teshigahara and writer John Nathan have much to say regarding the concept of feeling isolated or even like an expatriate during the sixties. Summer Soldiers is less aesthetic than most of Teshigahara's other works and instead feels indicative of the American independent film circuit that was on the rise in the early seventies; this isn't why the film is ranked last, but I do think its style is worth pointing out. For me, I just got less out of a film like Summer Soldiers — where most of its talking points have been made before in many stories across numerous mediums — than I did other Teshigahara works, but I do think it is a solid drama.

7. The Man Without a Map

Teshigahara worked frequently with writer Kobo Abe, and you can chalk up many of the fable-like natures of Teshigahara's prime to this collaboration. The last time this pair worked together was on 1968's The Man Without a Map: a noir-adjacent title that feels like a major precursor to the major neo-noir films of the seventies. Here, many loose ends are left as such; this is more of a character study and a mood piece than a narratively sound motion picture. That may not be your cup of tea, but I do love how Teshigahara plants us in the fog of mystery that only feels more and more debaucherous the deeper we get. A great noir is all about getting lost in the details; whether those details are refined or murky is up to the storyteller. With The Man Without a Map, we are surrounded by a haze of a puzzled mind.

6. Princess Goh

It feels difficult to separate the next two films, given their "conjoined" nature, so I will be covering them back to back. Of the two sister films (including Rikyu; more on that shortly), I find Princess Goh — Teshigahara's final film — slightly weaker, but this follow-up to the story of tea master Sen no Rikyu (where we are adjacent to his successor, Oribe Furuta (and, of course, Princess Goh) is a pensive reflection. Both of these films feel like a mindset more than anything else, and part of that is the luxury Teshigahara provides for us with the jaw-dropping settings and details; if he was keen on making films that feel like installations, works like Princess Goh are successes in this way. Some may find this film slow and empty, but I find Princess Goh immersive.

5. Rikyu

Teshigahara's penultimate film is very similar to Princess Goh. I just think that Rikyu has a bit more going on narratively, as if we are witnessing an entire life in the span of the last years of the title tea master's life within the Sengoku period (with the threats of war forever persisting). Otherwise, all of my compliments for Princess Goh apply here: Rikyu is a film that I want to leap into and explore (outside of the political struggles and the darker themes, of course). As much a lesson history and culture as it is a living painting or exhibition, Rikyu is visceral cinema.

4. Antonio Gaudi

Teshigahara's only feature-length documentary is Antonio Gaudi. In short, it is nothing more than a city symphony look at the architectural designs of, well, Antonio Gaudi and his influence on Catalan modernism. What sounds boring is actually breathtaking. The documentary is virtually nothing more but shots of these structures and designs, but what elevates this film from being a lazy and uninspired slog is Teshigahara's ability to make us feel like we are in an art gallery (albeit the illusion of a three-dimensional one and in a massive space that can house all of these structures). In an abstract way, we are told very little about Gaudi, his life, and his methods, but we are left to his legacy (via the form of the constructs that remain) to allow our minds to wander and come up with our own assessments; if anyone understands that art is not meant to be spoon fed to observers, it's Teshigahara. The end result is almost overwhelmingly beautiful, and Antonio Gaudi is an extravagant documentary that tells us very little yet shows us everything.

3. Pitfall

After a handful of short films, Teshigahara's debut feature film, Pitfall, is one hell of a way to start a career. This surreal journey into a paradise of abandoned souls is a metaphor for life and how all dreamers will wind up in the same predicament: existential confusion. What starts off as a visual conundrum turns into a ghost story for the ages: an exploration of how we disassociate in order to survive. Focusing on the middle class environment in Japan, Teshigahara and Abe examine how much we are willing to shed from ourselves in order to survive with conditions none of us agreed to by choice. This could have been left as a philosophical quandary, but Teshigahara makes Pitfall a near-psychedelic confession of hopelessness.

2. The Face of Another

Teshigahara's answer to the horror genre, The Face of Another, was maligned when it premiered. I understand that the film was ahead of its time, but the idea that such a compelling and hypnotic film could be despised confounds me. This could have simply been a spooky film about someone who wants to don a new face, but Teshigahara and Abe instead make this a sad affair: an engineer who is butchered in a workplace accident who simply wants to freely exist again without qualm. I cannot express the flurry of feelings I get watching The Face of Another, but if I could try, the phrase "haunting heartbreak" comes to mind; Teshigahara doesn't make our experience easy by delivering a multitude of responses to what could have been a hacky assessment of a tragedy. Instead, The Face of Another festers in your soul; it feels like it has been jettisoned from a spaceship from another world, and yet this film and its story feel like it could happen to us. Films don't get much eerier than The Face of Another.

1. Woman in the Dunes

I think most would agree that Teshigahara's greatest achievement is Woman in the Dunes, and as strong as his filmography overall is, to me, there is no contest here. One of the best films in all of Japanese cinema, Teshigahara and Abe's perverse fairy tale (of sorts) leads us to a man lost in the middle of nowhere, who stumbles upon an emancipated village that one can seemingly never leave. Is this paradise, or is this prison? What a layered look at life this film is. This village acts as the existence of all, and its inhabitants are civilization: all the aimless souls who wanted to find purpose in life, and they've been bestowed such opportunities (usually not by choice). Our protagonist studied entomology, but within this village, he is given expectations he is to meet; which is his destiny? Did he ever have a choice?

If the film was played via a different angle, there would be something serene about our lead finding a place to live and people to frequent here (including the title character: a widow who, also, is trying to make sense of it all). Instead, Teshigahara forever keeps us on our toes; what would we do in such a situation? Do we accept the life that we've been given, or continue to try and seek something new and more fulfilling in the endless desert? There is no right answer; when Teshigahara grants us the perfect images of cinematographer Hiroshi Segawa, all we can do is stare. The best films, art, poetry, and literature leave us questioning what we have just experienced to the point that it changes us as people, as observers of these mediums, and as spirits. Hiroshi Teshigahara's Woman in the Dunes is all of the above, and it is a monumental masterpiece of cinema.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.