Arco

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: This review is for Arco, which is a film presented at the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival. There may be slight spoilers present. Reader discretion is advised.

It is difficult to feel inspired in the day and age of artificial intelligence removing the livelihoods of artists. When the English-dubbed version of Arco had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, I believe I counted around ten or eleven production company title cards that preceded the film. It has been a trend to mock this many studios funding a film in online posts, I’ve noticed, but that saddens me when I don’t see desperation: I see unification. Upon completing Arco, this rang true as I saw a film that many producers wanted to give life to and allow to see the light of day. Its animation is graceful yet choppy, expansive yet limited, creative yet simplistic; it is the product of human dreamers. During the Q & A period, programmer Robyn Citizen asked Arco filmmaker, Ugo Bienvenu, and the film’s producer, Natalie Portman, a question that was pressing on my mind during the entire feature film: the importance of creating art within a world being taken over by AI. The two guests agreed that there are beautiful sides to technology and what humans are capable of, but art is as essential as innovation and that we cannot afford to lose what makes us human, no matter how dark everything appears. There was Bienvenu, the theorizer, who conjured up a film about aspiration within devastation, and Portman: the catalyst who vowed to help make this film happen. Despite all of the horrors of the world, they both find joy and hope in despair.

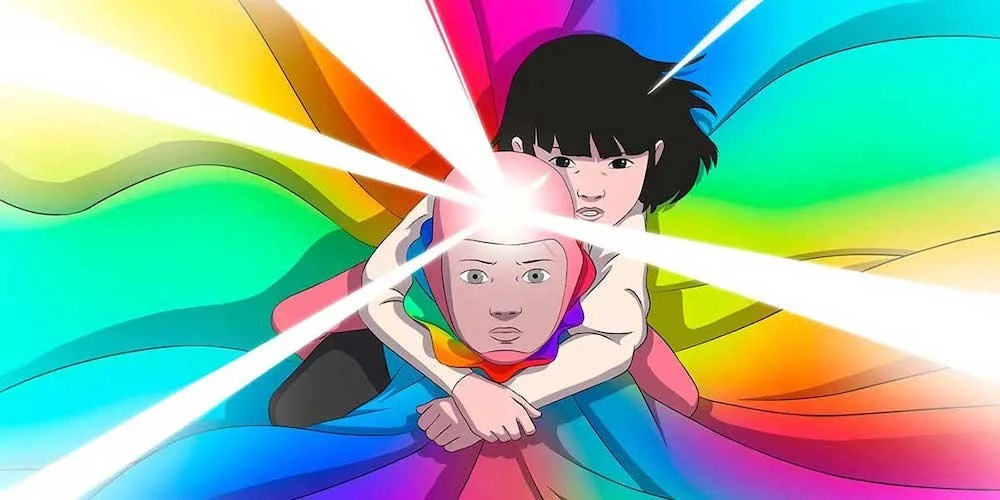

Arco is a film that is meant for children to be able to do the same: to not give up no matter how bad the odds are. The titular Arco is a child from the future: one where humans are capable of time travel and whose trails create colourful tracks (Arco attributes the sight of rainbows in our reality to these nomads: perhaps a magical explanation as to why they exist). Arco is too young to be traveling alone and, against his parents’ wishes, tries to fly anyway, finding himself crash landing in a different time period: one with child Iris, whose parents are almost never home (an android babysits her and her baby brother). Iris lives in a time period distant from ours, but not too far ahead: it is a world that is about to be on fire and fall apart. Arco’s future is one where the tides washed away civilization, and humans had to adapt to higher forms of living (structures in the sky) in order to survive. As Arco has gone missing, his family vows to find him. So do three bumbling stooges dressed in primary colours: Dougie, Stewie, and Frankie. They have been hunting Arco for twenty years. What is their motive? I’ll leave that for you to find out.

Instead, it is Iris who finds Arco first and brings him home. The two children bond while trying to help Arco get back home via any means necessary. Bienvenu creates an imaginative world where even lawn sprinklers can be fascinating (they are curious little devices where water spews through mechanical, clapping hands); it is this kind of creativity that makes a film like Arco sparkle (we are still capable of coming up with such amusing feats). Many viewers have compared Arco to the works of Hayao Miyazaki, and I can understand their viewpoint. However, I felt like a likeness that hasn’t been discussed is how much Arco felt like an extremely distant cousin of Fantastic Planet. It is far less cynical, absurd, or challenging, but Arco retains the French sense of wonder via animation that combines sociopolitical themes with spellbinding creations. How could such a beautiful future be so horrific? Arco is also fit for children, whereas I would concur that Fantastic Planet is not.

While a coming-of-age tale, Arco descends into a commentary on the fragile environment and worrisome progression of civilization. It is clearly a warning flag for children who are indeed facing a very tough road ahead. I am highly concerned to bring a child into the world as it stands right now, not knowing what I would be bringing my offspring into, but a film like Arco is a reminder that adults have to be as resistant as our future generations are. We cannot afford to let our kids deal with the consequences of all. As Arco concludes, we are left with a fairly bold choice: a lasting pan across a dialogue-free, photographic montage; a bittersweet depiction of how our past dictate our future, and that the present is permanent. It is an indication that nothing would have remained if it wasn’t for the youths who refused to give in to the inferno and the end of society. It is a bleak image with enough aspiration to encourage those of us who are afraid to wake up every morning. When you watch a film like Arco, you see countless hours plugged into making a film this passionate, lush, and mesmerizing. You see those who refused to quit, and those many aforementioned studios who wanted to help these animation marathoners keep going. Sure, an animated film won’t save the world, but a film like Arco reminds us why at least artists are crucial: they restart our hearts and cleanse our souls when society makes us feel hopeless.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.