Marty Supreme

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Note: This review contains minor spoilers for Marty Supreme. Reader discretion is advised.

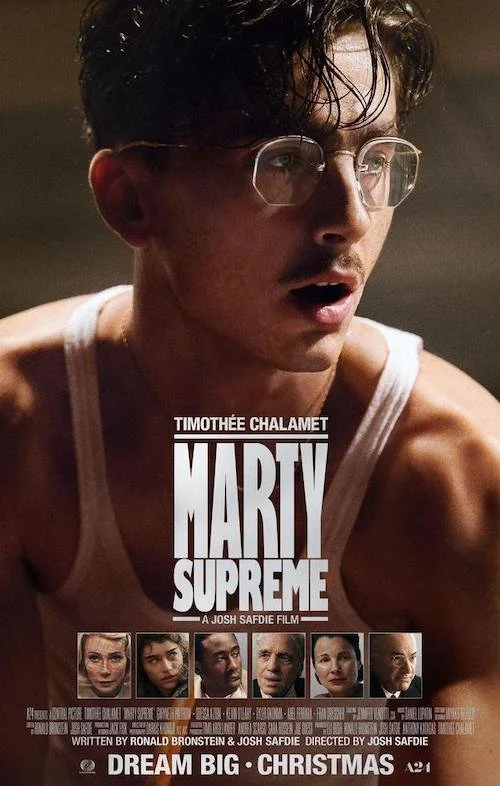

The film poster for Marty Supreme simply states “dream big,” as if this were a lazy result after an AI prompt was used. Why does one of the most anticipated films of the tail end of 2025 have such a basic tagline? I view this as a statement that one can sell anything if they have enough confidence. If you get too wordy, you lose your audience. You can lose your message. To simply state “dream big” is to have faith in the two words being used. In that same breath, to possess the sterility of such a corporate mentality is to unmask the artificiality of such a sentiment; do corporations really care if you succeed? Marty Supreme is heavily promoted as the next big sports drama, but most of the marketing neglects to truly highlight the stress that comes with watching this motion picture. That pressure should come as no surprise, given that this film is directed by Josh Safdie who has teamed up with his brother Benny to create similarly intense motion pictures like Good Time and Uncut Gems. To me, the marketing for Marty Supreme is all ego; the film itself exposes the reality underneath the charisma.

Marty Supreme is not a biopic (thank Christ), yet it is curiously inspired by table tennis superstar Marty Reisman and the athlete’s propensity to be a showman while playing; this shifted the focus away from the sport itself and towards the athlete partaking in it. Marty Supreme is actually Marty Mauser, played by Timothée Chalamet, and, sure, he carries Reisman’s braggadocios nature while also being a whole different breed of intense in that same breath. Chalamet channels two of his real life passions — basketball and hip hop — in this central performance by extracting the hostile and vibrant confidence of ballers and rap stars and placing it in this mousy, nerdy oddball. Marty is slightly cross-eyed, boasts a bit of a unibrow, and gawks at whatever he is analyzing, yet he has more charm and sway than I likely ever will. Chalamet completely transforms here, embodying the naivety and narcissism necessary to make Marty seem like a partial God in the eyes of those he comes across and betrays while forever remaining unstoppable in his own eyes. This doesn’t include his actual athleticism; Chalamet’s Marty backs up his apparent delusions when he turns into a table tennis titan. At least during those matches, Marty is legitimate. The world comes to a stand still. He is that guy.

Except when he isn’t.

Much of Marty Supreme is about how his dreams are actually problematic. A native of New York in 1951, Marty is great at table tennis, this is true. He has won championships. However, to get to these places, he has taken many big risks and crossed many supporters. These include his helpless mother, Rebecca (Fran Drescher), his girlfriend Rachel (Odessa A'zion) — who is married to someone else — and his friend, Wally (Tyler Okonma, otherwise known as Tyler, The Creator). We see how Marty uses anyone around him for his own gain by using tall promises, big words, and other deceptive tactics. At first, this appears to be the maneuvers of a genius; we quickly learn that these are hail-Marys out of desperation. Things only get worse right from the jump. Marty is prepared to win the latest British championship as he has done so before and egotistically puts it all on the line; from making financial promises to those back home, to going hog wild with the accommodated room service while over in London. However, he doesn’t take into account a new Japanese opponent, Endo (Koto Kawaguchi): a legally-deaf table tennis pro who doesn’t get distracted by the crowds around him, and uses a special kind of paddle to his advantage. Of course, Marty cannot accept accountability and blames Endo’s paddle — amongst other things — for his loss in the final round. So, what about all of those financial gambles he just made? He didn’t win the big jackpot, and now he has to answer for it.

Marty Supreme is one of the most thrilling films of 2025; its speedy pace allows the film to never ease up.

While biting off more than he could chew, Marty is prepared to try and get the attention of ink mogul Milton Rockwell (Kevin O’Leary) while wooing Milton’s wife, retired actress Kay Stone (Gwyneth Paltrow); the audacity of this chap. Naturally, these threads also come back to bite Marty in the ass after he is away from home and on tour for eight months following his loss in England; Milton has taken an interest in table tennis after Marty’s efforts and now wants to host his own sponsored event in Japan (to capitalize on Endo’s rise in popularity); meanwhile, Kay is acting on stage in New York, and Marty must stick his nose in other people’s affairs (as he is accustom to). By this point, much is already unraveling. Those room service bills have come back, and Marty’s behaviour has him presently banned from future competitions until his debts are paid off. Marty’s method of getting enough money to even go to London have come back around like a mean form of comeuppance. Rachel has her own twist to offer as well. These are all plot threads that pertain to different characters, but because Marty suffers from a serious case of main character syndrome, he finds a way to make everything either an advantage for him to leverage or a tribulation that will get in his way of competing again.

Like other Safdie films, Marty Supreme reveals itself to be a kinetic downward spiral that never eases up. I don’t know how he keeps doing this — and credit goes to Benny Safdie as well, given his involvement with prior films — but Josh Safdie’s ability to keep upping the stakes and figuring out new narrative flows and knots to complicate these stories (while never getting convoluted) remains outstanding. What helps this film go the extra mile is its sports identity. Sports films are always stuffed with kitsch and fabrication: synthetic cheers and gasps that usually lead to the same end results. Marty Supreme boasts a bit of this energy, but it also knows what makes the genre tick. You cannot just watch a sequence of athletes competing and expect to care. You get invested due to the backstory; you learn what makes these people tick. Consider ping pong in the history of film and how frequently the sport is used as a form of mockery or criticism. When you watch Marty Supreme, table tennis becomes the game of gladiators. There is a hint of the silliness attributed to the sport present, just to prove that stigmas exist surrounding a game many love and cherish. When Marty Supreme turns on the bright lights, ping pong becomes art. Safdie recognizes that we care because this matters to Marty; we see what this means to him; what he’s been through to get here; how much is riding on a win.

While many other sports films cannot stray away from their action sequences and will find excuses to game away, Marty Supreme is begging for Marty to find his way back into a proper competition. The title sequence sees a ping pong ball with Marty Supreme on it and this sets the tone. Marty gets the first serve and tries to make proper moves to gain power. As the film progresses, he loses control and he truly is the ping pong ball being battered back and forth from adversary to adversary. A major turning point is when Milton reminds Marty that he is nothing more than a form of entertainment, telling him “You have no power here.” It was apparent that Marty Supreme is a rare sports drama to acknowledge that the faces of these sports are, in fact, pawns of the bigger system. This also extends outside of sports and leisure. Is Safdie powerless in the film industry? Perhaps he feels like he is. Oftentimes, the famous faces only have so much power which comes off as limitless to the masses; it is the wealthy behemoths behind the curtain who truly hold the reins. However, much of Marty Supreme is Marty trying to regain the next serve.

Marty Supreme succeeds with bold choices to help it stick out from other sports films.

One of the biggest selling points of Marty Supreme is the eclectic and unorthodox cast, but I do believe that Safdie has something to say with who he casts. Outside of Chalamet, nearly everyone else is known for their voice or eccentric personality; O’Leary’s booming cynicism is a mainstay of Shark Tank and American entrepreneurship; Paltrow has become a bit of an odd ball in Hollywood thanks to her questionable ventures and ideas (but, shit, can she act); Okonma was once the controversial rapper of the world and is still known for his uncompromised sense of humour; Drescher has always been recognized for her drawl and cackle. This also applies to the highly unexpected cameos who pop up; Ted Williams is literally the Man with the Golden Voice, whose chatter went viral when a passerby recorded the previously homeless radio host on the street; Penn Jillette is a Las Vegas staple in part due to his magnetic voice that effectively sells the notions of magic tricks; NBA legend George “The Iceman” Gervin is a pivotal personality of basketball in the seventies. To me, Safdie and company picked names and faces who would have you clinging onto every single word, amidst all of the hysteria and anarchy. This tactic works, all while reminding you of the weight of these words thanks to whom is saying them. When O’Leary talks about the corruption of the world, you know that the real person feels this way and couldn’t care less about how this line of thinking affects others. That’s a world driven by competition, be it through sports, business, or the process of simply staying alive.

Marty Supreme takes place in the fifties but there is a clever anachronistic choice to make the musical accompaniment heavily based on the sounds of the eighties. Daniel Lopatin — of Oneohtrix Point Never fame — returns with another gorgeous blend of retro synths and chilling ambience; these are the sounds of a reality that is quite a distance away from the fifties. Then, there are the popular needle drops, from Alphaville’s “Forever Young” to Tears for Fears’ “Everybody Wants to Rule the World.” For me, these choices are for two main reasons. Firstly, the height of the sports film arrived in the eighties, so the nostalgia for the most obvious cuts — like Chariots of Fire, Hoosiers, and the like — is a key factor in riding this high. Secondly, we are forced to look backward; every time an eighties song plays above footage of a fifties story, we feel like someone — perhaps Marty — looking back on their salad days, wondering where it all went. Like anyone who peaked when they were younger (like a varsity athlete who amounted to nothing), we are forced to forever look backward. What transpires after this? Does Marty ever figure it all out? His struggles are nerve-wracking. Towards the third act, I noticed the Bubly can in my hand was beyond crushed out of my hands clenching every so often; be prepared to bring a stress ball to spare your armrest.

It becomes apparent that Marty Supreme is secretly Safdie’s The Graduate, and Marty is floundering about to try and figure out his purpose. He is frequently told that his table tennis dreams are insane and unrealistic, and that he should grow up and lead a normal life. By the end of the film, we are given something as bittersweet as the final shot of The Graduate. Are we graced with tears of joy, or does Marty fear the uncertain road ahead? Much of the final act is hinged on Marty’s realization that his dreams simply will never come true; too many bridges have been burned. However, if he can at least remain true to himself for one instance, maybe his goals will briefly come to fruition; it’s better to be a superstar for fifteen minutes and fade into obscurity than to forever be a loser (and, given his track record, Marty is a loser more often than he is a winner in life). Once Marty’s facade wears off on audiences, we no longer wonder if he will become a front page face of Sports Illustrated; we become concerned for his well being. We don’t care about him skyrocketing to fame. We just don’t want him to die. Marty Supreme is a constant roller coaster ride that never slows down. It kicks off like a hilarious Martin Scorsese caper before doubling down on its threats and becoming one of the great crime films of the year. On the note of the aforementioned auteur, Josh Safdie does feel heavily inspired by Scorsese overall (the use of the name “Marty” is coincidental, I’m sure), and I feel like Scorsese would see this film influenced by his own works and think, potentially, that Marty Supreme is “absolute cinema.” I’m sure you will feel the same way with this highly entertaining, nerve-wracking affair.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.