Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Steven Spielberg Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Directors

Who doesn't already know Steven Spielberg? Quite possibly the biggest director of all time (or, at least, of contemporaneous times), Spielberg is the kind of filmmaker who has won over all walks of life. If you talk to people who rarely watch films, chances are even they know Spielberg. What I find a little ironic is that Spielberg's films are quite literally what Hollywood embodies now, yet his rise came in the New Hollywood movement with a couple of flashes of a different kind of director: someone who loved to flirt with danger. His actual debut is Firelight back when he was 17 and in 1964, but that film hasn't seen the light of day since it was released (Spielberg prefers for it to be hidden forever), and I will not even attempt to cover that film in this list (I will be covering every other feature film, mind you). So, instead, I — and Spielberg — consider his true debut 1971's Duel: a game of chicken between an innocent man and a massive semi-truck from hell. This film is indicative of what the New Hollywood movement was all about: different ways to assemble a film in a fresh and dynamic fashion while exploring the kinds of stories that were once impossible to make due to the Hollywood Code that came before.

After a couple of films of this nature came Close Encounters of the Third Kind: a different kind of New Hollywood film. This was far more sentimental, as it was derived from Spielberg's broken home dynamic (he would reflect on the difficulty of growing up in a family afflicted by divorce in a number of his motion pictures). Thus set the standard for Spielberg and for Hollywood: a unique kind of warmth and emotion. Of course, the director would explore other genres and styles, but that kind of cinematic hospitality became his signature style. It would succeed again and again, too, with a number of his films — from E.T. the Extra Terrestrial to Jurassic Park — becoming box office megahits. In fact, that very term came from the success of his New Hollywood thriller, Jaws, since lineups to see this film were so long that they expanded a number of blocks in each city. Spielberg is that impactful in the history of film.

His style (at this point) must be the most mimicked of all filmmakers, but what many of his disciples fail to realize is that Spielberg doesn't go into each film trying to get that fuzzy feeling that is so often copied or parodied; if anything, all of the pale imitations feel as soulless as an AI generated result if the prompt was to recreate Spielberg's token style. Why Spielberg's brand of warmth works is because he is almost always exploring himself in his projects; again, he is constantly focusing on the difficulty of growing up in a divided family, but Spielberg also channels his Jewish identity (from his family who were tortured and even killed in the Holocaust, to the antisemitism he grew up with), the destruction of war (from stories passed down to him by his father and other loved ones), the kinds of films that made him fall in love with cinema (adventurous journeys, science fiction epics, and thrilling capers), and much more. Spielberg is forever putting himself on the line with his films; that is where his warmth comes from (a mutual relationship between what part of himself he offers each film, and the time we have carved out to witness these mini-sacrifices).

That isn't to say that I think Spielberg's work is untouchable. He has made enough great works to warrant the praise that he is forever attached to, but I also can admit that I find some of his films quite dull; there are only two or three films I could call outright bad, but, even then, I have also seen far worse by directors whom I like even more. Even these worst works don't feel artificial (except for maybe one): they still resemble a director who is revealing something about himself for the world to see, and that makes them watchable (even if they aren't great by his standards). For the most part, Spielberg is quite consistent, and he has both great and so-so works from each decade that he has worked in (he is the only director to be nominated for an Academy Award across six different decades for this very reason). I don't think there's much need for me to go deeper into Spielberg's life and career than this because his films already do so much of the talking; I will allow them to proceed from this point on. Here are the films of Steven Spielberg ranked from worst to best.

34. The Lost World: Jurassic Park

The only time that I have felt like a Spielberg film was soulless was The Lost World: Jurassic Park. This is clearly a sequel meant to make big bucks after the success of the previous Jurassic Park (and, quite frankly, the only one that matters; yeah, I said it). The Lost World feels derivative, duller, and — honestly — far more annoying, whereas the original was inspirational, thrilling, and unique (it is now so heavily stolen from, even by its own franchise). However, I do not blame Spielberg entirely. When his friend George Lucas succeed with a franchise like Star Wars, you cannot fault Spielberg for trying to follow what has worked before; in fact, Spielberg has seen his own success in this way with the Indiana Jones series. Then again, this film just isn't it, and it is clearly his worst film to me.

33. Hook

This one is going to sting, and I apologize for the many of you who hold Hook dear to your heart. To me, this film is quite a mess. There is a lot of noise, commotion, and juvenile behaviour that just hasn't aged all that well. However, I do see where the love for this film comes from, and it's mainly due to the quite stellar world building (thanks, in part, to the impeccable costumes and sets), and Robin Williams' heartwarming performance certainly sets the bar high enough. I just don't have the nostalgia goggles necessary to blindly accept Hook as a great film when it is quite flawed and dated.

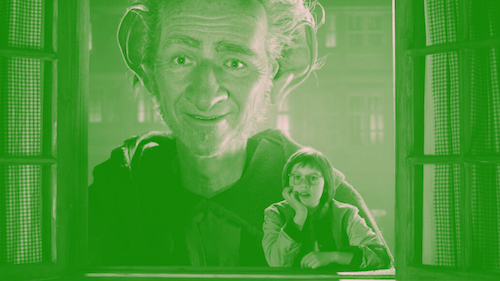

32. The BFG

At least Hook had time to age strangely. The BFG was wobbly from straight out of the gate. I've ranked it slightly higher because I find it barely less irritating, but it suffers from many of the same issues as Hook, including the immaturity (The BFG actually has fart jokes which is almost always a turnoff for me; sorry for being so pretentious). At least we have Mark Rylance as the titular big and friendly giant who is always pleasant to watch, but there's a reason why The BFG doesn't get discussed anymore: it is highly forgettable (to Hook's credit, at least it inspired many who watched it at a young age, but that's more indicative of when Hook came out as opposed to its quality; The BFG barely exists).

31. Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull

There's a reason why George Lucas stopped Star Wars at three films. Oh, wait. He didn't. When he returned with The Phantom Menace, the prequel film was a disaster; yes, even with the nostalgia many have for it, I wouldn't dare call it a great film. Spielberg similarly bit off more than he could chew with this fourth Indiana Jones film which was the worst of the series (more on that shortly). Kingdom of the Crystal Skull loses some of its mystery and heart in favour of effects and convolution to the point of being bothersome; each Indiana Jones film asks you to suspend disbelief with their fantasy or science fiction elements, but Kingdom of the Crystal Skull goes way too far with its ridiculousness. At least it's kind of fun in a sloppy way, which is more than I can say for James Mangold's Dial of Destiny which is a bore and a chore (and now, officially, the worst Indiana Jones film).

30. 1941

This is a Spielberg film, but it has co-writer Robert Zemeckis' thumbprint all over it. Otherwise, I'm not quite sure what Spielberg was hoping to accomplish with the war comedy, 1941 (maybe it was meant to be his M*A*S*H of sorts?). What I will say is, despite the muddled tone and datedness, Spielberg directs the shit out of 1941 far more than it deserves; there are some legitimately strong sequences in a film this out there (at least Spielberg was treating the film with a sense of severity, even if it never finds it for itself). I'd recommend this one to Spielberg purists and completionists alone, but it isn't a terrible film; just a strange one.

29. Always

We have reached mediocre territory now, and I do have a soft spot for Always (I assure you that it's not solely because of Audrey Hepburn's final on-screen appearance, as lovely as she is and seeing as she is one of my favourite stars of all time). I like the idea of a romantic film where one partner dies and is trying to reconnect with his widow from the afterlife while she falls in love with someone else. It's actually a clever concept when done right (then again, the film it is based on, A Guy Named Joe, isn't exactly well executed, either). Always is just far too sugary, kitschy, and soft to give off the emotional resonance required to stick its landing, and I find the film objectively mushy; I still don't mind watching it when it is on, despite its sogginess.

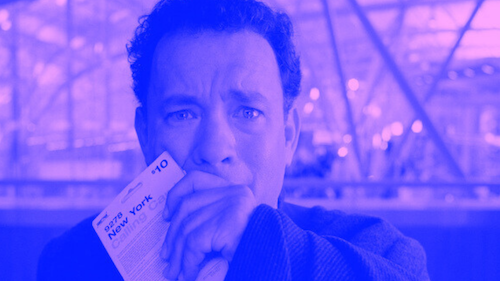

28. The Terminal

Here's another one that is better in concept than it is in execution. The Terminal takes portions of the true story of an immigrant who lived in the terminal of an airport for almost two decades and tries to enhance it. I feel like the film starts off with promise, but because it lingers with its same concept for so long, its niche wears off rather quickly. Yes, our protagonist lives in an area where most people arrive or depart. I wish the film explored his existential concerns a little more with such an unorthodox premise. Instead, Spielberg aims for inspiration rather than reservation, and The Terminal comes off as a film that is frequently waiting for the magic to appear (it could have been a great introspective conquest instead).

27. Ready Player One

That's it for the simply-mediocre films in Spielberg's career. We are now at the films that are at least somewhat good, albeit flawed enough to stick out. Enter Ready Player One: an action epic that is such a flurry of ideas and concepts that it is difficult to not be wowed at least marginally by it. Unfortunately, what the film has in spades (nostalgia, recognizable properties all uniting, gorgeous effects) it lacks in substance; what is meant to be a depiction of classism and a fuller story of an abandoned world in favour of a digital escape becomes a by-the-numbers action romp. I'd argue that Ready Player One is really fun in the moment but it becomes almost instantly forgettable as soon as it is done (outside of maybe some great action sequences).

26. The Sugarland Express

Spielberg's second official film is a forgotten little gem of the New Hollywood movement. The Sugarland Express is a rare time where Spielberg is seemingly tossing a lot at the screen and hoping that all will stick. To his credit, quite a bit does stick, from the unbridled electricity of the film (stemming mainly from a highly fun performance by Goldie Hawn) to crime film elements that actually feel at least a little consequential (something that doesn't happen too frequently in Spielberg's safe-space cinema). The film is a little wonky but it is cohesive enough that I think it is a little underrated when it comes to the bigger conversation of the New Hollywood films that showcase signs of rebellion; The Sugarland Express is hardly a taboo film, but it's nice to see Spielberg get a little out there (outside of the couple of obvious examples like Jaws).

25. Amistad

Spielberg's historical epic about slavery is a school staple for many; how many of us watched this in history class? There is much to admire, from the performances and ambition, to the meticulous production, and these are the elements that keep us watching. However, Amistad suffers from being just a little too slow and quite overlong (a film is welcome to feel large in scale, and not always via runtime). Spielberg can occasionally get carried away with the duration of his films (a handful of the films I've ranked higher are excellent outside of feeling even just a smidgen too long), but it feels almost at its worst with Amistad: a film that could have been quite great if it wasn't as drawn out as it is.

24. Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom

We are in pretty good territory, folks. The first sequel to Raiders of the Lost Ark (and the first to boast the Indiana Jones name) is quite good. It's interesting seeing Indy return but with a bit of a fatherly dynamic for little Short Round (who has blossomed and become Oscar-winning actor Key Huy Quan), especially in a film that gets as dark as Temple of Doom (maybe Spielberg was aiming for a coming-of-age film that exposes a child to the dangers and evils of the world). I don't feel like the film is too grim like others have said, but I do find the film at least a little derivative of its predecessor; Temple of Doom feels like a bit of a repeat with not too much to offer otherwise. That isn't necessarily a bad thing, as Temple of Doom is still loads of fun and what you'd expect out of an Indiana Jones film (except replace refrigerators with snakes). It is nice to see Spielberg at least partially return to the horror genre, here.

23. Empire of the Sun

Here's another film where Spielberg got a little carried away with its runtime (two-and-a-half hours, here), but Empire of the Sun is still quite a riveting watch. With a young Christian Bale (who would only go on to be one of the greatest actors of his time), we coast through war-torn Shanghai via a prisoner of war child. There's an intriguing dichotomy here between the way this youth sees his surroundings (albeit without stupid naivety; he's able to piece together what is going on himself) and how us adults watch the film and have a larger context of the severity of things. Some other war films may toy with whimsy too much to the point of treating their audiences like dolts; Empire of the Sun doesn't do that, thankfully.

22. The Adventures of Tintin

As if Spielberg was itching to do another Indiana Jones film while learning his lesson from Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, he kind of delivers that with his adaptation of The Adventures of Tintin. There are a couple of other voices heard in this animated action film, from the technological prowess of producer Peter Jackson to the snippy and quick-witted comedy of co-writer Edgar Wright. Tintin is still intrinsically Spielberg, with the fleeting sense of action and the curious fascination with adventure. As a child who grew up with the TIntin comics, I feel like kid me would have adored this film; as an adult, I appreciate how closely this film brings the source material to new life.

21. The Color Purple

I am conflicted with The Color Purple. On one hand, the film is as well acted as it was once decreed, and it is still just as moving as it once was. However, I am a little flummoxed by how off its depictions of race-related issues feel. That isn't to say that a Caucasian director cannot tell Black stories, but there does seem to be something missing with The Color Purple: maybe the hint of whimsy, as if all will be okay in the end because this is a Hollywood picture and we are protected by the magic of movies. I suppose the sentimentality does get a bit in the way of the gravity of what The Color Purple is meant to represent. All in all, I do think this is quite a good film, but it maybe isn't quite the success I once thought it was as a teenager when I first watched it. It just feels too simplified when it is going over some highly complicated matters.

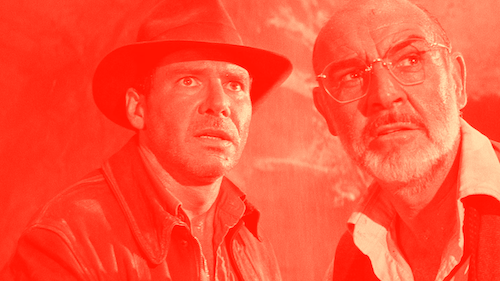

20. Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

Indy was once a father figure in The Temple of Doom, and so he must now become a son in The Last Crusade. The third — and what should have been last — film in the Indiana Jones series sees our academic hero confess his entire life to us; he's no longer a mysterious archaeologist who happens to have the stamina and athleticism of a gymnast, but, instead, someone who was obsessed with artifacts from a young age who was coached and learned how to become an unstoppable force. With that backstory in mind, his adventure with his father, played by Sean Connery, becomes something far larger than just another mission. With Indy looking at both his future and his past in one last hurrah during the present, The Last Crusade could have sent this trilogy off on quite a high note; instead, Indy just couldn't help himself but return for yet another quest, could he?

19. War Horse

To me, War Horse is kind of like Empire of the Sun, except replace a child going through the horrors of war with, well, a horse. I do think War Horse is a rather great film, but it does annoy me that there are hints of a masterpiece here; if Spielberg was even bolder with how little dialogue there could be with this horse gallivanting throughout a planet being ripped to shreds by World War I (think of the donkey's journey in, say, EO, and how much of the film relies on us providing the animal protagonist's inner thoughts and emotions which we feel in spades). What War Horse is instead is a quest for a horse to be reunited with its owner, and that's quite special as well. We still get to see many different aspects of battle through War Horse in a way that provides something fresh from the other times Spielberg has approached the genre; I just see the signs of something that could have been magnificent, and I cannot ignore them.

18. The Post

The Post is almost a brilliant film. I am a sucker for motion pictures about journalism (I saw Spotlight in theatres almost ten times; I have issues), and The Post is four-fifths an excellent film about journalism. Spielberg presents this study about the Pentagon papers quite thoroughly, with a star-studded cast giving it their all and quite a pulpy screenplay that is quite representative of reading a strong article (part of the appeal of journalistic films). It is when the film approaches its ending that Spielberg gets a little carried away with his signature brand of sugariness and it does detract from a film that was previously quite matter-of-fact; I know that essays are meant to carry their biggest punches for the end, but that doesn't mean that they get ambitious to the point of feeling almost artificial, either. Otherwise, I really like The Post, and I will forever wish that it stuck its landing without trying to truly sell you on something you were already committed to.

17. Catch Me If You Can

Ah, yes. Frank Abagnale. It isn't Spielberg's fault that Catch Me If You Can relies on the conman's confessions being true, because the grifter-turned-author's memoir of the same name has now been accused of being largely fictitious (which is typical for a man known to be a liar, I suppose). Doesn't the film lose a bit of its luster now that we aren't sure how much of it is real? It isn't like another Leonardo DiCaprio film, The Wolf of Wall Street, where we know we have this unreliable narrator trying to trick us while Martin Scorsese still exposes us to the truth Jordan Belfort doesn't want you to know; Spielberg made Catch Me If You Can under the misapprehension that all of these tricks of the trade were true. Even so, this is quite a fun film that does feel like you are forever riding on the seat of your pants through Abagnale's many deceptions to get by in life. It just is missing that oomph it once had, I'm afraid.

16. Lincoln

Lincoln would have been a top-ten Spielberg film if it wasn't for one point that bothers me to this day; it is, once again, simply too long. Spielberg feels the need to add another twenty (or so) minutes to a film that feels like it is resolving via its own volition (mainly to tell us stuff we already know: that President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated; sorry for that spoiler, I guess). Before its additional ending is a rather riveting — albeit sanitized — look at a president who is caught in the middle of wings, viewpoints, and moments in history; he understands this position as well. Lincoln is played magnificently by the greatest actor of all time (Sir Daniel Day-Lewis), but even he gets occasionally matched by an even-stronger performance by Sally Field as First Lady Mary; it is thanks to their acting, and the strong work of the rest of the cast, that much of Lincoln reads as a commanding political thriller that will keep you seated (even if you already know how this one ends).

15. War of the Worlds

Spielberg is usually far more sympathetic with his depiction of life from other planets, so something like War of the Worlds comes off as a bit of a surprise to me when viewing his entire career retrospectively. Then again, you can read this film as a war drama as opposed to a science fiction epic, and I think it will hit even harder in this way; the extra-terrestrials can be a tabula rasa for any nation invading you, as to plant you in the position of anyone who has ever been attacked. What comes next is an exposition of action and CGI mastery: a spectacle by a director who knows a thing or two about making them. I'm not sure why the initial response to War of the Worlds is so lukewarm because it is quite a captivating achievement (can we also agree that it looks far better than a certain other adaptation of the H. G. Wells novel?).

14. The Fabelmans

I wonder if The Fabelmans will begin to dip under the radar a little bit, seeing as it was certainly the talk of the town when it first came out. When I first saw the film, I recognized it as a purely Spielbergian affair, which makes sense given that it is quite autobiographical in tone (down to showing how Cecil B. DeMille's The Greatest Show on Earth inspired him to make motion pictures; I'd argue that even Spielberg's worst film has greatly surpassed this source of influence). If you look at The Fabelmans simply as a film, it is quite good but only that. However, I see something else that elevates it to a certain level of special: a veteran director using the power of cinema to have a conversation with his younger self. When you understand The Fabelmans as a metaphysical conversation of this nature, it is quite exemplary, and how Spielberg never beats his younger self up but, rather, tries to console him is exquisite.

13. West Side Story

While potentially the least necessary film Spielberg ever made (that's saying a lot, considering that he made a fourth Indiana Jones), I think many of us feel the same way when I say that his version of West Side Story was shockingly great. I view it as almost neck-and-neck with the Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins Best-Picture-winning adaptation of the same name; the previous film plants us in Broadway and soaks us in gel lights and the pitter-patter of the concrete meant to mimic a stage, while Spielberg's answer utilizes the film camera as a means of allowing us to dance with the participants. The 1961 film is more artistic while Spielberg's version is pure technical marvel, and, in ways, that can be the better way to go with a film as lively and bombastic as West Side Story (I'm not saying that Spielberg's film is stronger, but the fact that we can make these comparisons at all is actually astonishing to me when this should have never worked).

12. Bridge of Spies

When I expose my minor gripes with films like The Post and Lincoln, it's because of a certain motion picture called Bridge of Spies: a film that is just as narratively ambitious as these other two while knowing when to call it a day (the screenplay by Matt Charman and both Coen brothers certainly helps with knowing what paths to take and how to resolve plot threads naturally). This optimistically tense Cold War thriller is fun because of how frequently you aren't sure of what exactly is going on. With a Spielberg film, you can estimate that there will be a happy ending and that all will be okay, but, somehow, Bridge of Spies still makes you second guess everything. With a depiction of the political struggles on both a micro and macro level, Bridge of Spies is quite a contemporary triumph by a man who proves that he still has what it takes time and time again.

11. Minority Report

On paper, Spielberg is just too uplifting and optimistic to adapt a work by the famous cynic Philip K. Dick, but Minority Report just works; if there was ever a genre that Spielberg surrendered himself and his tendencies to time and time again, it was science fiction. Especially in the day and age of fake news, police brutality, and many other privacy-encroaching concerns, a film like Minority Report has aged incredibly well thematically. What also helps is that Spielberg's team deliver special effects and ideas that hold up as well (these have to be important in an action film, after all), creating a world that is fascinating to watch (but certainly not one that we'd want to live in). Despite the fears presented to us, Spielberg's signature consoling nature makes Minority Report both a cautionary tale and a reminder that we are in this together.

10. Duel

Ignoring Firelight, Spielberg's debut feature film is Duel, and what a thrilling way to start a career. What I think is now a rather underrated film (sure, people know and love Duel, but I'm staking my claim by placing it in Spielberg's top ten here, which is clearly a big deal), Duel is indicative of the New Hollywood movement's quest to push the boundaries of cinema made by someone who clearly already knew what he was doing. What a constant force of a film, as we watch a salesman go toe-to-toe with a demonic behemoth of a truck that will not stop following him. This is a film that doesn't ease up for just over an hour, presenting us with nothing but chills the entire time; furthermore, how difficult is it to actually have a proper, cohesive, and complete story told via a vehicle that is essentially nothing more than one long action sequence? Duel is no joke. Not only was it a sign that Spielberg should be making motion pictures, it remains a career highlight over half a century later.

9. Jurassic Park

Everyone loves Jurassic Park still thanks to the undeniable staying power of the breathtaking blend of practical and digital effects, the thought-provoking story (how far is too far when it comes to scientific breakthroughs), and, duh, the dinosaurs. That is why we still champion the film. Then, you consider what all of this meant back in 1993 (a double-header year for Spielberg where he released Schindler's List, no less; he was operating on a different astral plane, here). What an absolute marvel of a film Jurassic Park is: a prehistoric playground for children to be spellbound by and a domestic drama within the confines of an adventurous thriller for parents to nibble on. There's something for everyone here in what appears to be a near-perfect formula of substance and spectacle that has been attempted by many other sequels that all are atrocious by comparison (even Spielberg himself struggled to capture lightning in a bottle again with The Lost World).

8. Munich

As time goes on, my respect for Munich climbs. What could have been a rah-rah macho-fest of following the team chasing down the terrorists responsible for Black September at the 1972 Olympics instead turns into a majestically horrifying analysis of the human condition: how far down do these acts of corruption extend? Everything Bridge of Spies does right, Munich does but with the extra sense of dread that is evident even after the film resolves. There will never be enough blood spilled to stop the act of slaughter in the world. What starts off as a union of the globe's best athletes becomes a case study that all citizens of the world are united in the many ways they were not previously aware of; Munich sheds light on how dark our reality truly is, and the people who found out the hard way so the rest of us wouldn't have to.

7. Raiders of the Lost Ark

Raiders of the Lost Ark is kind of like Led Zeppelin's "Stairway to Heaven" at this point. Try to ignore how many films it inspired, how over-used its images and sounds are (including that iconic score by Spielberg mainstay John Williams), and how exposed you have been to Indy and anything he has ever been attached to. Head back to 1981 and consider how instrumental Raiders of the Lost Ark was to cinema as a whole, with its rejuvenation of the adventure genre, its heightening of action cinema, and many other major shifts in cinema. More importantly, Spielberg filmed Raiders of the Lost Ark with the fascination of a young child (yet the much-needed wisdom, maturity, and expertise of a trained master of his craft), allowing audiences to enter a world of wonder, thrills, and discovery.

6. Saving Private Ryan

Spielberg's second Best Director Academy Award was for Saving Private Ryan: a beloved war epic by many. Even though his signature grace is throughout the film, Spielberg dips into the darkness of being in battle enough to make this feel like at least a semi-impossible mission; that shocking preliminary battlefront sequence confronts the urgency of war, the split-second choices necessary to stay alive, and the instant weight of the aftermath of it all. Saving Private Ryan sprawls over much ground and time, drilling home the idea that each life saved is a miraculous feat; you can only imagine the worth of the millions of lives lost (if this is what it took to save just this particular one). Saving Private Ryan uses movie magic to get us out of the depths of hell while reminding us of the many who fight for their country and at what cost.

5. E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

Spielberg shares his imaginary friend in a film known affectionately as E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial: this friend is a product of Spielberg trying to find comfort in his broken home. What is a science fiction family film on the surface is truly a domestic drama deep down: a boy in a house divided who acknowledges that this lost alien is also in need of feeling like it belongs somewhere again. As Elliot tries to get this wandering soul back to its home planet, we see that both loneliness and sympathy are part of the universal language. Spielberg's vulnerability results in one of the great family pictures ever made: a film that is sure to melt the hearts and lift the spirits of all who come across it.

4. A.I. Artificial Intelligence

When A.I. Artificial Intelligence first came out, it maybe came across as well intentioned but confused in its approach. Half a century later, not only is this film prophetic about the state of the world and its over reliance on technology, it saw the future of how films would be read. Spielberg completed the dream of his friend, the late Stanley Kubrick, with a science fiction masterwork that is as chilling and hopeful as the styles of both directors (Spielberg alleges that much of the film's darkness actually came from him and not Kubrick; I suppose we will never know). What we see here is the irresponsibility of creating artificial life for loaded purposes and abandoning what we construct when it no longer serves us a purpose; by creating a child android, we see the metaphorical heartbreak of something knowing it is now deemed useless and unworthy of love. Spielberg may have a bad habit of making overtly tender endings, but A.I. Artificial Intelligence is one that deserves it; the final frame of a complete household (at what cost) is one of the greatest moments Spielberg has ever made, and it earns the tears it draws from my eyes.

3. Jaws

There are two masterpieces from Spielberg's New Hollywood era. One is indicative of what the era brought, and the other is an enhancement of what the movement could be. The former is Jaws: a sterling horror film that took the constant dread of being stalked from Spielberg's Duel and dials it up to eleven with the danger of a great white shark invading a beach. I know it was for budgetary reasons (the shark didn't look as realistic as Spielberg and company desired, so they tried to show it less), but having the aquatic beast appear so far into the film via a tremendous jump scare is such a marvelous revelation (it is also proof that Spielberg likes to play nice, but he can easily mess with his audiences if he ever desired to). Even the blips of whimsy here are used to almost toy with viewers; the film is getting more hopeful down to John Williams' iconic score (which was previously cuing us for dread with two simple notes), so things should be okay, right? Wrong. Jaws was such a major success because — after decades of Hollywood films that pandered to us — it was such a change of pace to feel this yanked around by a film (and a filmmaker who knew his monumental power so early on).

2. Close Encounters of the Third Kind

The other New Hollywood opus is Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and this film reminded us that not all of the films of the movement had to be rebellious. They could just show us the way to the future of American cinema ahead. Spielberg replaces danger and chills with mystery and wonder in this science fiction film. In the same way that Roy cannot ease up until he discovers what is out there in the skies above, Spielberg was incessant on pushing through filmmaking to find something new. He was a part of a new team of artists who was changing the cinematic landscape, but he also loved the spectacles that he grew up with and wanted those to come back. The middle ground is Close Encounters of the Third Kind: a film as delicate as it is titanic. Of the New Hollywood directors, I always felt Spielberg was the most romanticized as if he was the Francois Truffaut (of the French New Wave movement) of America; it's no coincidence that Truffaut shows up in a small part in Spielberg's film here. Sometimes, innovation can be made softly and warmly, not via force and abrasion; these were two directors who knew this best.

1. Schindler’s List

Even though Spielberg has clearly made a slew of great films and a couple of masterpieces to boot, there was no other film that could top this list for me than Schindler's List. Let's ignore that it is his only film to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards (it's still shocking to many that he didn't win before this 1993 film). I have never seen a director confront his past and present as marvelously as Spielberg does here. There's the obvious, like the reflection on the atrocities of the Holocaust and how detrimental it was to millions of people and the entirety of the Jewish community worldwide; the film's flash to the present to focus on the surviving Schindler Jews (the real ones, no less, and not actors) is a cinematic choice that still chokes me up to this day (after being very acquainted with this film for most of my life). There's also Spielberg the director and not just his cultural identity. Spielberg rarely goes dark, but in Schindler's List, he is prepared to get obsidian with his proper, unvarnished observation of how bad concentration camps truly got; there are deaths in this film that still feel real, even compared to the works of much gorier filmmakers. In that same breath, Spielberg's softness shines through at precisely the right moment: when all need saving from complete misery and devastation.

Oskar Schindler is depicted as a complicated person who did a magnificent deed to save many Jews during the Holocaust, and it is fortunate that Spielberg didn't sugar coat who this person was (it is important to know that bad people can have changes of heart; how else can we try to make this world a better place?). With one of the great character arcs in cinema, Schindler can no longer turn a blind eye to the monstrosities of war and bigotry, as he uses his means that once aided his greed (his factories) as a haven to rescue Jews who would otherwise be killed. How sad is it that decades later that the lessons of a film like this are still not being listened to? How can anyone still engage in such savage acts as genocide when works like this one have shown us their true impact time and time again? This film won Best Picture and is celebrated as a masterpiece, so it isn't like people haven't seen it (or films like it). We may not be able to change the world as a member of a political party or a business mogul, but films like Schindler's List remind us to at least try to be an Oskar Schindler: saving or helping just one life is incredible in and of itself.

An uncompromised film that pummels you with the worst capabilities of humanity, Schindler's List is also meant to show you the brilliance that compassion possesses. We are all human beings. We are as capable of murder as we are saving the lives of others. The world isn't so black-and-white, and one of the reasons why the film is in greyscale is to embody this notion: we are forever caught in the middle. There will always be something that we cannot ignore; in the case of Schindler's List, it's the little girl in the red coat that captures Schindler's eye. Do we then decide to keep neglecting what is around us, or do we do something? The little girl in the red coat resembles both choices: what happens when you do not act, and why you should help those who need it. For much of my life, Schindler's List was a formative film that changed everything for me. I didn't know that Spielberg could even make a film like this (then again, maybe he didn't, either). All I do know is that Schindler's List is one of the most powerful, moving, brilliantly-made, and crushing films ever produced, and I consider it Steven Spielberg's crowning achievement (and one of the greatest films of all time, even still).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.