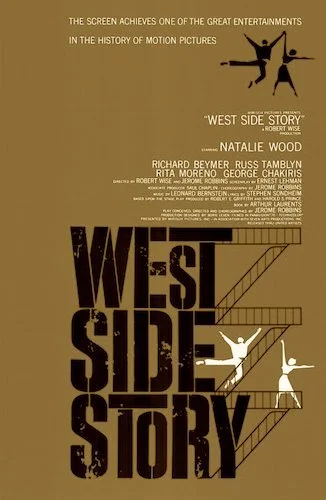

West Side Story

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. West Side Story is the thirty fourth Best Picture winner at the 1961 Academy Awards.

All things considered, this is the strongest adaptation of Romeo and Juliet ever put to the silver screen. As silly as that sounds, Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins could funnel the hyperdrama of William Shakespeare’s tragedy in a way that felt natural. The more straight forward renditions don’t really present as worthy of a divide between two parties like West Side Story does, with its modernization of the tale, and the transformation from families to gangs. With the addition of cultural influence (those who find the positives of living in America, and those who don’t), West Side Story tosses in a whole influx of reasons why Maria and Tony shouldn’t be together. It isn’t out of convenience. West Side Story truly pits these two against the world.

Adapting Shakespeare was not the only goal. West Side Story is the film version of the ‘50s Broadway production of the same name. The film tries to capture the stage’s advantages, and almost every single effort transitions well into Technicolour. The gel lights from the rigging above. The setting cut into specific angles. The prances from spot-to-spot. You are aware right away that West Side Story is mimicking theatre, and you fortunately kind of forget that relatively quickly. Without cutting down on the Broadway factor, West Side Story blurs these lines enough to not be distracting.

The threat of authoritative figures — including police — plays a prevalent theme in West Side Story.

So, you have three major collectives. The Sharks are a Latin American gang that wish to fit in. The Jets are the locals that don’t want to share their turf. The law involves any outside authoritative force willing enough to step in between the two opposing sides. The layout of these characters allows for tension to circle around like a brooding storm, rather than just hop back and forth like a contest. You don’t know where the hurricane is going to hit, but the rising anguish makes the likeliness of destruction more probable at any given minute. West Side Story starts off with enough hatred, but it cleverly leaves enough of a gap for blood to boil to a high enough temperature as the film goes on.

With all of the chaos about to ensue, we get to the nitty gritty with Tony and Maria: a forbidden romance that young hearts wish to make true. The music in the film already works so well as an inner dialogue, as Stephen Sondheim’s lyrics turn Leonard Bernstein’s music into chit-chat discussions. Between Tony and Maria, we feel like we are hearing the voices of the silenced, in full effect. As a musical, West Side Story really works, because the melodies act as the pulse of Manhattan, and the lyrics are the retained thoughts (either of passion, or of rage) waiting to spill.

Tony and Maria meeting; their setting locks them in like a jail, forbidding them of freedom.

Steven Spielberg is aiming to release his version of West Side Story in 2020, but I see absolutely no need for that. The 1961 original is as fine as it needs to be. There likely isn’t anything that can be added to better it significantly. It’s destined to be a great-enough musical drama that hits all of the right notes. Plus, let’s think about that ending. Spielberg may blow it, if I may be honest. Recall the urgency of the climax, which you may have not expected. West Side Story is content in following up to its build ups; all of this talk about striking, and yet we never felt prepared. The resolution was absolutely daring. A remake is bound to mess it up, even with all the technological advances. A West Side Story in 2020 will feel too pristine, and too produced. It belonged in the 60’s: where bright lights bled through the Technicolour film, the soundtrack smudged together to create a booming serenity, and the theatrical cheese meshed well with the incoming gravity of New Hollywood. It is a product of its time.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.