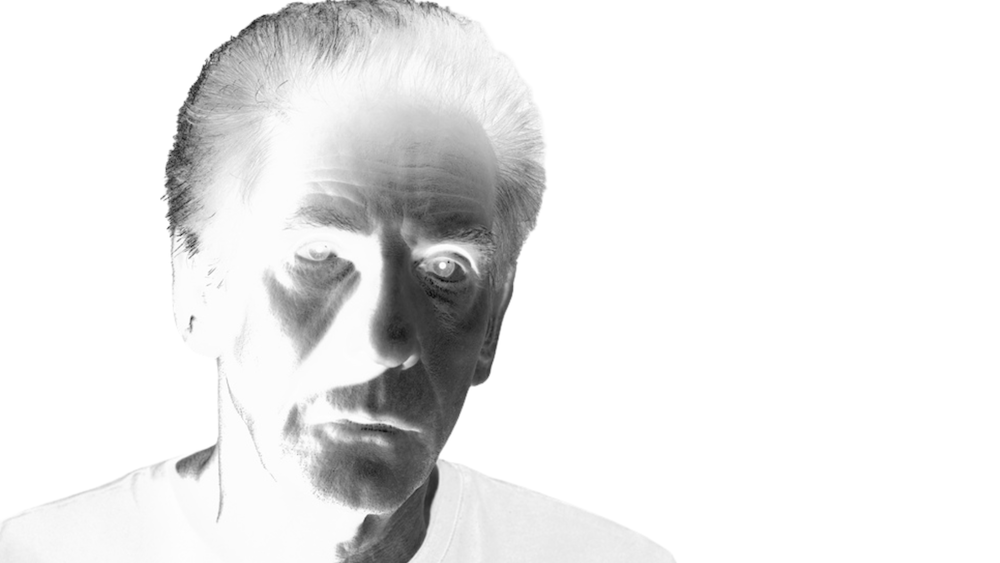

Filmography Worship: Ranking Every David Cronenberg Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Directors

It is telling that one of Canada’s greatest directors of all time is a master of horror cinema; it feels indicative that a national titan indulges in the darkest and strangest capabilities of humanity. Considering that Canada is known for generating many weird films, Cronenberg feels like the figurehead of consistency; here is an auteur who has made numerous daring films without ever feeling compromised. Even his most mainstream films never feel as though he has sold out to the masses; he invites you into his world instead. The godfather of the body horror genre, Cronenberg has been misappropriated as a believer that the human body is a monstrosity. This makes sense, given how many of his films feature deformities, viruses and growths, and many other bodily abnormalities. However, even as a devouted fan of his, I felt forever changed when I watched Cronenberg get interviewed by a fellow horror-savvy director, Guillermo del Toro, and someone in the audience asked the former about his reasons for making the human body a monster. Cronenberg was taken aback, as if his entire filmography was misunderstood. He would go on to state that he finds the human body beautiful and a miraculous machine. It was then that I finally understood him.

His films do not try to make us feel sick about our own vessels. He has us empathizing with the depiction of these gorgeous creations slowly breaking down, morphing, or even dying. Cronenberg has also been a major admirer of entomology, incorporating larvae, metamorphosis, and insect-like designs into many of his projects. In short, he is fascinated by the ways that bodies — human or bug — operate to the degree of wanting to see them get deconstructed or challenged. His films operate similarly. While he may not be an avant-garde artist by way of his narratives, Cronenberg frequently contests what plot can look like, and many of his conclusions are bittersweet or open ended. If there’s anything that Cronenberg doesn’t like settling for, it’s normalcy. This can stem from his obsession with science fiction magazines at a young age, which led to a lust for science and storytelling and — subsequently — the enrollment at the University of Toronto with a degree in Honours Science; he would later switch his major to Literature. While studying, Cronenberg made two student films: Stereo and Crimes of the Future. He would then garner financing from the Canadian government, strike up a partnership with another Canadian great — Ivan Reitman — and the rest is history.

With many horror films under his belt, it’s safe to say that Cronenberg is one of the greats of the genre. Having said that, to only acknowledge his brilliance in horror is a disservice. Cronenberg has also tackled other genre films and has a string of magnificent thrillers later into his career that cannot be ignored either. At his very worst, I think Cronenberg has countless great ideas, and even his weakest film is at least worth investigating because of his peculiar perspective. However, I think there is much to celebrate with Cronenberg, including at least a dozen films I’d recommend without reservation. Most of these films were not loved upon their release, proving that Cronenberg has always been a polarizing figure; it goes without saying that his motion pictures encourage us to step outside of our comfort zones, embrace the unknown, and acknowledge the extent of the human body, psyche, philosophy, and perseverance. Most of all, Cronenberg’s ability to make hideous creations, situations, and personalities have alluring and — dare I say — beautiful aspects to them is unparalleled; we learn more about ourselves via his uncompromising cinema. Be afraid. Be very afraid. Here are the works of David Cronenberg ranked from worst to best.

23. Stereo

Cronenberg’s debut film, Stereo, is far from terrible, but it is very much what it appears to be: a student film with hints of promise. With frequent voice over narration that details the 35mm footage that we see, Stereo makes a statement on what life would be like if we were rendered incapable of being able to speak ever again and could only communicate via telepathy (you can see the intended irony here). Maybe Cronenberg was intending on commenting how film is in and of itself a form of language, and there is some depth here that shows that Cronenberg had talent and promise at a young age, but Stereo is understandably simplistic. It’s no surprise that Stereo is his weakest film, but that’s how it should be; great directors should only grow, not fail to meet the standard of their very first attempt at making a motion picture.

22. Crimes of the Future (1970)

Much of what I said about Stereo can be applied to Crimes of the Future (obviously not the one that Cronenberg released decades later, but his sophomore student film). The silent-esque filmmaking remains, and here Cronenberg tries to tackle the concept of fetishization in his own way. A subject Cronenberg has mastered since, it’s clear that he doesn’t quite have much to say with Crimes of the Future, although you can tell in each frame that he is itching to say something. This is an early seedling that shows potential, but there’s only so much a director can do with little money, inexperience, and a lack of wisdon; however, it wouldn’t take long for Cronenberg to start making works of brilliance shortly after Crimes of the Future. I do want to note that there is very little overlap between this and Cronenberg’s film of the same name, meaning that the 2022 feature is not a remake despite the similarities.

21. Maps to the Stars

What felt like Cronenberg’s swansong, Maps to the Stars, was potentially the end of a fantastic career with a significant dud. The director persisted on making abnormal dramas in the twenty-first century, and I would argue that most were successful to varying degrees. However, Maps to the Stars looks great and has committed performances; I’d call it a messy misfire otherwise. What is meant to be a deeper look at the Hollywood experience is instead a surface level observation of the horrors of stardom. I feel like Cronenberg has inadvertently tackled this concept better in past films like Videodrome, and Maps to the Stars comes off as a little heavy handed otherwise. This would be the last film Cronenberg directed for eight years before Crimes of the Future, and maybe this hiatus is what the director needed to get back into the swing of things.

20. M. Butterfly

I always appreciate directors who are willing to deviate from the norms that they have created for themselves, and such is the case with Cronenberg and M. Butterfly: a political romantic drama film surrounding the stage of opera. While it is exquisite in aesthetics and there is an intention for narrative depth here (particularly the queer plot thread of a diplomat falling in love with a Peking Dan performer — a male actor disguised as a female), M. Butterfly feels a bit sluggish and disengaged. It’s not to say that Cronenberg cannot make a straight forward drama, but M. Butterfly almost feels like an alien who is trying to mimic being a human; the signs of humanity are all there, but the soul is missing.

19. The Shrouds

Grief is one of the most inexplicable horrors out there, and Cronenberg’s attempt at deciphering it is The Shrouds, made in memory of his late wife, Carolyn Zeifman. Using technology to communicate with the dead, The Shrouds creates the impossible: a reunion with our lost loved ones. Cronenberg then challenges that notion via an attempt to find peace within tragedy: those who have departed must remain departed. I think The Shrouds is a decent observation of loss and I cherish Cronenberg’s candidness on the big screen; I do think that this film is a bit of an unfinished idea that would feel revolutionary if it was fully realized (then again, maybe we aren’t meant to ever fully understand death).

18. Fast Company

Cronenberg’s strangest film doesn’t involve mutation, aliens, parasites, or killers; it dabbles in race-cars (oh, the humanity). It was only five films in that Cronenberg took a hiatus from making horror or thriller films to produce Fast Company: a full-on sports action film (and an early attempt by Cronenberg to speak the language of Hollywood producers; something he’d perfect for his own gain by the eighties). Fast Company is at least a fun watch mainly because of how different it is for this established auteur (I like the stunt driving choreography, for instance: something I usually don’t associate Cronenberg with). However, on its own merits, this is a standard action film that may not show you anything you’ve not seen before.

17. Crimes of the Future (2022)

Cronenberg returned from his eight-year break with Crimes of the Future (again, there is barely any relation to his student film of the same name). It was a welcome comeback not just because it was nice to see a juggernaut working again, but because it was Cronenberg’s first outright horror film since the nineties. Having said all of that, Crimes of the Future feels like a distilled Cronenberg film: it’s his style in every way, but it doesn’t feel as impactful as what he has been capable of time and time again. A commentary on body modification and performance art, Crimes of the Future had us rethinking our bodies again — this time alongside the numerous directors inspired by Cronenberg (like Julia Ducournau and her film, Titane). While not a career defining moment, this was a standard return by a coveted visionary.

16. Shivers

Cronenberg’s first film after his student works is Shivers, and it shows. This early release is as obsessed with the hyper sexual and violent psyche of human beings as both Stereo and the first Crimes of the Future; this time, however, Cronenberg has a bit of a budget to work with. The film is short enough to not be a major bother (I was shocked to learn that most Cronenberg films are less than two hours long; he doesn’t mess around), but much of Shivers boasts an implied depth; if anything, Shivers is a fun horror film that doesn’t feel quite as robust as most of the director’s other projects (I do think this makes for a good pick for fright night viewing).

15. A Dangerous Method

I feel like A Dangerous Method should work better than it does. We have Cronenberg making a psycho-sexual drama involving the philosophies and teachings of Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud, with a performance by Keira Knightly as psychoanalyst Sabina Spielrein that is so committed that it treks into that uncanny territory that Cronenberg typically frolics in. At times, this is a compelling look at mental health and how it was treated and inspected generations ago. Otherwise, Cronenberg doesn’t go quite as far as he could with a film that’s begging to break free; I do appreciate his restraint, but not when it is to the extent of holding a film back. Nonetheless, A Dangerous Method is a commendable film that is willing to go dark enough to allow itself to stand out from other safer historic pictures.

14. Scanners

I may catch some flak for this, but I may not love Scanners as much as some people do. I think it is a good film but not a great one, and it feels a little strange to detail why when I consider most Cronenberg films fairly thorough with their tone and messaging: Scanners feels like the exposition of terrific moments in a decent film. Yes, much of the paranormal film is memorable, but I feel like enough of the downtime feels empty or simplistic compared to the standout sequences that it hinders the film. Still, while I think Cronenberg has stronger indie films from his early days, Scanners still boasts enough highlights that are guaranteed to blow your mind (hopefully not too much, though).

13. Rabid

Perhaps a late answer to counter-culture cinema like Easy Rider, Cronenberg’s Rabid kicks off with a motorcycle accident that then transitions into a vampiric feeding session, and finally into a chronic pandemic where the spreading disease cannot be slowed down. Is this a jab at the right wing accusations that sexy and gory films poison the minds of viewers, or just a sandbox picture for Cronenberg? Either way, Rabid is quite a fun experiment that feels complete enough to pop on any Halloween season (even if the film doesn’t quite compete with the greatest Cronenberg pictures, Rabid is bonkers and fun enough to not miss).

12. Naked Lunch

It is next to impossible to adapt William S. Burroughs’ postmodern novel Naked Lunch; the urban legend that the Beat Generation great dropped his manuscript, assembled the pages in any random order, and handed it in as is rings true when you read the novel. Instead, Cronenberg adapted Naked Lunch in the sense that his film tries to make sense as to how the novel was written: within a disgusting reality and an even worse mindset. The end result is far more cohesive than Burroughs’ novel (for better or for worse), and Naked Lunch redefines what an adaptation of a source material can look like (all things considered, it is beyond a considerable effort to the point that I’d call this oddball film a little underrated, especially if you like Cronenberg’s style).

11. Cosmopolis

As I have mentioned before, Cronenberg’s films are almost always polarizing when they are first released. I’m not trying to play prognosticator and arbitrarily pick a film that will become beloved, but I do feel like the tides may turn for a Cronenberg title I actually love: Cosmopolis. Another incredible adaptation of a challenging novel (this time, it’s Don DeLillo’s work of the same name), this is a bit more of a direct attempt to bring an impossible text to the big screen (whereas Naked Lunch was an interpretation); I’d argue Cronenberg’s film bests DeLillo’s novel, since the director is able to invite you into the stretch limousine (present for a vast majority of the film) as both a participant and an outsider. Cronenberg satirizes the extremes of high living with this brooding, stylish drama that feels like a limbo between reality and the nihilistic worlds the director frequently creates; we’re almost on the same wavelength as Cronenberg, here.

10. The Dead Zone

When I was a horror-obsessed teenager, I found Cronenberg’s adaptation of Stephen King’s The Dead Zone a little kooky, as if it was so detached from reality that it felt implausible; this psychic protagonist just didn’t seem tangible. However, as an older man, I understand Johnny Smith (played wonderfully by Christopher Walken) in the same way I’d look at Network’s Howard Beale: a well-intentioned, misunderstood prophet who is also dealing with the weight of their delusions and illnesses. The Dead Zone makes sense when you have lived enough to see just how ludicrous the world truly is, and it is then that you feel Johnny’s desperation to try and course-correct the future; my appreciation for the film is far stronger, and this time around I understand that the real world may be crazier than how Cronenberg depicts it.

9. Existenz

Maybe a psychological thriller about virtual reality and video games was seen as farfetched back in 1999 (something like The Matrix made more sense as a slice of action-film escapism with philosophical overtones), but I’d argue that Cronenberg’s Existenz has aged wonderfully (or disastrously, if you notice the film’s implications of what could happen to those who become addicted to living digital second lives). Cronenberg also uses this trippy premise as a means of exploring computer generated playgrounds, blurring the lines between a video game creator and player, and the game itself; how immersed have you ever been with a video game (likely not as immersed as the characters here)? Existenz was certainly ahead of its time, and I still find its concept enthralling.

8. Spider

Cronenberg veered away from horror in the early 2000s to focus on the crime thriller genre instead, releasing a trio of breathtaking films; while his horror output greatly outweighs his thriller releases quantitatively, I’d call Cronenberg just as great of a crime film director. Spider, the “worst” of these three films, is an extraordinary insight of how Cronenberg reads the mind of a murderer: with extreme murkiness and intrigue. So many other films feign the abstract psyche of disturbed individuals and miss the mark, but Cronenberg feels like he has transplanted himself — like a method actor — into the shoes of a schizophrenic episode (without ever getting hyperbolic). Does Spider try to answer any major questions? Absolutely not. Just in the way William S. Burroughs write Naked Lunch (the novel Cronenberg once adapted), Cronenberg accepts that the answer, sometimes, is how fragmented something is, not why it is fragmented. The human mind is a curious thing.

7. The Brood

We are now in masterpiece territory concerning Cronenberg’s filmography; you cannot go wrong with a single one of these films (unless your stomach disagrees). While Cronenberg always showcased potential even with his earliest works, the first film to feel like an absolute winner is his sixth feature film, The Brood: a horror flick made in response to his divorce to Margaret Hindson. The gravity of his personal life is spilled all over every shot of The Brood as he likens his heartbreak to psychotic therapy sessions, serial murders, and biological deterioration. What resonates here is that The Brood feels oddly possible: as if Cronenberg tapped into a new reality where this was not a work of fiction. He would be able to access this portal time and time again, but The Brood felt like the first successful attempt (and not just a horror film that is meant to transport you); if Cronenberg made a career getting into the minds of his unwell characters, The Brood succeeds because it was the first time he tried to figure himself out (at his lowest, no less).

6. Videodrome

Film and television are rotting the minds of the youth of today! Or, that’s what we’d expect parental figures to say back in the eighties, and Cronenberg dials in on these bogus claims by pondering what does cause brain rot (well before the TikTok generation). Enter Videodrome: a perverse body horror cult classic dealing with snuff films, brainwashing tactics, and a conspiracy that will leave you feeling like you have gone insane. Cronenberg taps into a strange realm of sex, murder, and sin in such a drastic way, allowing you to feel the disdain that yesterday’s generation will feel with contemporary art (but, in Videodrome, Cronenberg has created a timeless parallel that will always ring disturbing). With Videodrome, Cronenberg has you feeling like you have stumbled upon something awful, and there is no turning back; you have seen too much, and you are forever changed (all hail the new flesh).

5. A History of Violence

Cronenberg delivers a crime film worthy of sitting alongside the works of Martin Scorsese and Michael Mann with A History of Violence: a punchy look at karmic provenance and how it is impossible to escape one’s past of sin. In just ninety minutes, we get the thrills of action cinema, an entire backstory of a mysterious protagonist revealed via twists and turns, and a powerful message on how blurred the lines can be between immorality and doing what one thinks is right to protect their family. Is Tom Stall a great father? We are left to decide that on our own after we are delivered the film’s title’s promise; some actions are too deep, and they will define the actor forever. We learn that he is not a good person, but he tries to make up for his previous life by acting in the present; seeing Cronenberg regular Viggo Mortensen play both sides of the same coin is tremendous acting. A History of Violence is such a rush to watch and possibly Cronenberg’s best film to be accessible with most audiences (this may be as “Hollywood” as his non-horror films get, and Cronenberg doesn’t lose his grit nonetheless).

4. Dead Ringers

If a director is to examine the human mind, their results usually show at least two sides of the same personality. Cronenberg cleverly takes the 1977 novel Twins and makes a psychological horror film that takes identical brothers — both gynecologists — and studies how slight differences in their upbringing render them completely different individuals. Dead Ringers is a mind boggling affair with Jeremy Irons (at his very best) playing both twins at the center of this twisted experiment. Furthermore, Cronenberg uses the medical practices on screen as a means of displaying how easily the mind can betray the body; Beverly’s gynecological tools will remain one of the more fucked up ideas in any Cronenberg film. The end result is a cinematic Rorschach test: a vortex of all things genius and how intelligence can either set you for success or blemish you with insanity.

3. Eastern Promises

I’m not sure if it is a hot take to prefer Eastern Promises to A History of Violence, but I simply do. I feel like the last film of Cronenberg’s crime thriller trilogy (of sorts). If Spider places you in the mind of a complicated man, and A History of Violence plants you at the crossroads of a criminal’s second life, Eastern Promises is the most complete picture of sin where the backdrop is rife with transgressions. Danger surrounds us and our protagonists, as we follow a midwife caught in the middle of a shocking conspiracy (one that involves a baby left without a parent; a perfect metaphor for what it feels like when one discovers the true horrors of the world). What transpires is a long connection with the Russian mafia, with Viggo Mortensen’s career-best performance spearheading that subplot (sadly, Mortensen was nominated for an Academy Award the same year as one Daniel Day-Lewis for There Will Be Blood). Eastern Promises is an exhilarating watch that proves Cronenberg’s hypothesis when straying away from the body horror genre: humans are indeed our own worst enemies, but we don’t need any fictitious metamorphosis in order for this to be true.

2. Crash

I’ve always said that there are two types of film lovers: Those who love Crash, and those who love Crash. I’m not a big fan of Paul Haggis’ Best Picture winner. I adore Cronenberg’s erotic horror film which remains one of the most inexplicable motion pictures in the history of cinema. I love how it feels like this detachment from reality, as if we have been sucked into the television Videodrome style. As we watch these fetishists chase the ultimate vehicular high (a gang of people who find sexual euphoria surrounding car accidents), as if we are watching a crash take place before our very eyes, we are repulsed and yet we cannot look away. I feel like I am watching this symphorophilia take place within a frozen limbo: as if the world is virtually dead around these addicts (and, of course, why wouldn’t it be when nothing else matters but this orgasmic rush).

The climax (heh) of Crash has forever stunned me: a horrifying realization that surviving a fatal accident is somehow a curse. Crash likens sexual depravity to drug fixations, but its biggest terror is a minor revelation: this kind of fetishization can happen to anyone who has a mishap in their life. Now that terrifies me, even if I know Crash is melodramatic about what can happen (the film takes me to enough of a candid place that it feels entirely possible). As a result, Crash is Cronenberg’s sickest film because it takes you to that mindset to face this obsession head on: you are one step closer to being one of these characters than you ever wished to be.

1. The Fly

The most Hollywood Cronenberg ever got is with his adaptation of the 1958 horror film, The Fly; I think time has proven that this is one remake that is far superior than its source material. Even at his most “conventional,” Cronenberg doesn’t stray away from his aberrant vision. We may get Howard Shore’s soaring score and a narrative involving a romance that becomes complicated at the heart of it all, but The Fly is through and through a body horror classic that does not let up; some of the greatest practical effects makeup can be found in this film, especially during stomach-churning sequences (let’s not forget the infamous arm wrestling scene). What propels The Fly above many other horror films is its empathetic angle. As a metaphor for the AIDS crisis of the eighties (and, really, many other diseases, cancers, and ailments can be substituted here), The Fly is a painful rendition of watching a loved one slowly die. Once you experience grief, The Fly goes from a horror film to a tragedy (there is nothing worse than losing your favourite person).

You can attribute the terrors and sadness of The Fly to the hubris of inventor and scientist Seth Brudle: a madman who ventured too close to the sun with his teleportation machines. However, that doesn’t justify someone slowly dying, no matter how arrogant one got from their ambition. It’s depressing to see someone wither away to the point of being unrecognizable. On that note, The Fly is one of the only horror films to get me teary-eyed (nay, to make me fully cry); the Brundlefly wanting to be put out of its misery breaks my heart every single time I see it. If a truly scary film can also be emotional and beautiful at the same time, it has achieved traits of miraculous proportions; The Fly is that film.

In all honesty, deciding upon one Cronenberg film to top his filmography was a little tricky, and any of the top five films could fit; do I go with his best attempt at cinematic straightforwardness and narrative complexity with A History of Violence; should I select his strongest artistic statement with Dead Ringers; do I crown his best crime film (and most well-rounded effort) with Eastern Promises; or do I elect the most Cronenberg film, and one of the most daring risks in all of film with Crash? In the end, The Fly made the most sense after all was considered. It embodies all of Cronenberg’s best qualities as a director and storyteller while showing the special effects finesse, acting richness (Jeff Goldblum was robbed of any and all awards), and strongest emotional angle of any Cronenberg film. The end result is an exercise in exceptional horror filmmaking (or direction of any sort), and The Fly remains David Cronenberg’s magnum opus (although the competition was admittedly fierce).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.