Anemone

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

In Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, our two female protagonists begin to converge psychologically, biologically, and spiritually. This is thanks to a nurse who does the majority of the talking and embodies the personalities of both herself and her plus one: an actress who has gone mute. Persona breaks itself as a film, indicating the fragility of permanence; if there isn’t a proper bond between identity and being acknowledged by others, anyone or anything can fade into obscurity. Persona made us face the fact that our legacy is a call-and-response effort between us recognizing our own mortality and the world remembering our existence. Naturally, we get anxious when recognizing that we are losing ourselves (or are capable of doing so), and our mind plays the worst tricks on us when it falters. Thus, in the event that our brain caves in on itself and our thoughts and feelings get eliminated, we unwillingly forfeit ourselves as capable beings with identities. Persona understands the sacrifice needed to get this point across: the film committing the ultimate form of cinematic martyrdom and destroying itself (quite literally, at times).

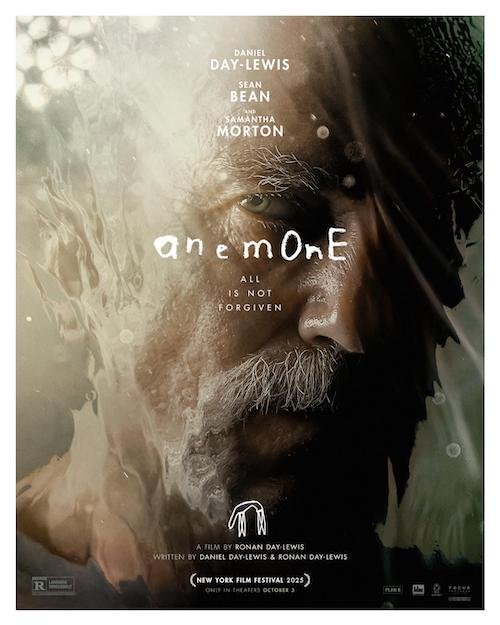

This leads to Anemone: one of the many films inspired by cabin-fever-psychological films (akin to The Shining, The Lighthouse, and many more titles). This is the feature length debut by Ronan Day-Lewis, son of acting legend Daniel Day-Lewis (I will go on record now — and many times before and after this moment — to declare Daniel Day-Lewis my pick for the greatest actor of all time; a hot take, this is not). While there is some mild curiosity surrounding whether or not son Ronan could make a great motion picture, the major draw for Anemone is father Daniel’s return to acting after eight years of inactivity (since his magnificent turn in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread); he stars alongside Sean Bean and Samantha Morton. There’s the extra incentive that both Ronan and Daniel co-wrote the screenplay together, so you can see Anemone less of a nepotistic favour by father Daniel and more like a proper collaboration within the Day-Lewis household; this feels nobler, wouldn’t you agree? Still, the question remained: could Ronan Day-Lewis direct a great film? I doubt anyone would question the acting capabilities within Anemone, so all of the contemplating rested on the film itself. The hype for Anemone was fierce, but it feels like the film was released as if the hype never even existed in the first place; it has been whispered into existence after all of that anticipation.

This is because Anemone can look and sound as good as it does and boast the acting caliber that it possesses, but it cannot escape its fate as a so-so indie film that was fortunate to have all of its involved talent. What Anemone actually is is a decent idea that is never truly fleshed out: a psychological drama that festers too much on simplistic backstory. You can rehash common ideas and reveal similar truths to the point that nothing that gets shared feels vital. If a Labubu collector has told you ten thousand times that they have collected a new Labubu, you will still only ever know this person as a Labubu collector. Anemone revels in its core themes of friction and regret enough times that we only learn little bits of information between the two central brother characters. I suppose Anemone is meant to depict the ambiguous rift between these siblings due to their pasts, and you could feel that tension. The problem is, you could feel that tension right away, and Anemone devotes a majority of its run time to creating this uneasiness. It never really gets as deep as it would like, nor does it encourage us to do the digging ourselves. Finally, it saves the bulk of its experimental turns for its climax, which feel severely out of place compared to the remainder of the film (which is, typically, as bare as can be). Again, existence is a call-and-response exchange. If Anemone isn’t sure of what it is as a film and doesn’t know how to get us to search within it, what is this film?

Anemone isn’t scared to get strange, but it doesn’t quite know how to go about its risks.

The film begins with a retelling of The Troubles (the thirty year conflict of Northern Ireland) displayed via childlike illustrations: an indication of a youth who is traumatized and permanently affected by their upbringing. We are then transported to England in the late nineties. Ray (Day-Lewis) is a recluse who lives in the middle of nowhere. He is awfully religious, His older brother, Jem (Bean) pays him a visit with the condition that Ray will finally return home; they have been estranged for around twenty years. At home, there’s Jem’s wife, Nessa (Morton) and their son, Brian (Samuel Bottomley). Anemone cuts to Nessa and Brian frequently, and you are meant to wonder about these confrontational vignettes; instead, their sequences feel like clips from a short film that got cut up and interspersed between the actual Anemone sequences; this is not a holistic experience. Through multiple lengthy monologues (excuses for Day-Lewis to act the hell out of his scenes, which I will never say no to), we learn that Ray is reeling years after having fought as a member of the British military and feeling responsible for what he did during The Troubles; thus, he lives off the grid in solitude. Jem has a similarly tricky history, but he represents those who can face their regrets head on, while Ray cannot stand to face himself.

Throughout Anemone, there is an ongoing threat of the unknown: an external force that looms. The trees rustle. The sky is grey. There are long stretches of silence, even when Ray and Jem share each other’s company. This builds up to an apocalyptic climax of biblical proportions, involving a hail storm, what appears to be a massive oar fish, and some kind of celestial being that I never thought would wind up beside Daniel Day-Lewis (excuse me, Sir Daniel Day-Lewis) in any capacity. Just when the film is finally promising to shatter itself under the weight of its own iniquity, it resolves itself and opts for a more hopeful ending instead. While I appreciate the triumph, I cannot shake off how Anemone is brutally uncertain of what it wants to be: an analysis of a fragmented mind, or the curing of a shattered soul. It could easily be both: it just doesn’t know how to be. Daniel Day-Lewis is terrific as Ray, even with the film’s shortcomings, purely because much of this man’s agony feels intrinsic; his cries are not frequent, but they feel like they have been pent up within him for decades.

Aside from this major highlight (and the more surreal moments actually carrying a punch; cinematographer Ben Fordesman is largely to thank), Anemone is a bit of a mess. The film festers around common ideas without evolving as much as it ever could; it believes that it is being pensive or mysterious. The other actors are held back by a screenplay that feels akin to a door-to-door salesman trying to force you to buy a water heater: they’re both spewing a lot without saying anything at all. Bobby Krlic’s score feels almost too impactful, as if the musician known as The Haxan Cloak (a conjurer of deeply unsettling ambient-electronic tracks) was hired without the realization of what he was capable of (with a film that cannot keep up). Deep down, there is a film that is tethered to The Troubles and the ongoing hurt caused by this conflict: a motion picture that likens the tainted heart to extreme loneliness, and candid declarations to celestial escapes. Instead, we have a portfolio of ideas that are slammed together, with enough successes that make Anemone not a complete disaster; then again, this is the same film where Ronan Day-Lewis directs his father to recite a monologue about feces (yes).

I love bizarre cinema, but being strange for the sake of being strange doesn’t feel honest. It’s too bad because there is clearly heart put into this film with everyone’s best interests on full display, and I don’t think that Ronan Day-Lewis is fully incapable of making a film (enough of Anemone shows hints of potential). However, as it stands, Anemone will be known and remembered for being Daniel Day-Lewis’ return, an ongoing parade of hit-and-miss experiments, and nothing else. I do love when the film works, and I want to appreciate the film more than I do, but I have to work with what I have. Psychological cinema is some of my favourite because of the relationship that gets established between me and a vulnerable film. If Anemone cannot certify what it is or what it hopes to accomplish, it isn’t a complete enough film to stand on its own legs. If it cannot be whole, it cannot shatter itself like it hopes to. If it is incapable of making itself comfortable and at home, it cannot get us to escape to where it wants to take us, either. A film that gets us to reflect on ourselves must be sure of itself; Anemone is not. In order to get that call-and-response exchange that Anemone is begging for, the film has to be fluent in its own makeup for us to fall under its spell and not be distracted by inconsistency. It neither sets itself up or destroys itself nearly enough to matter. For a psychological drama that is hoping to break the mold, Anemone doesn’t get that far at all because — all things considered — this is a film that barely exists.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.