The 101 Scariest Film Moments of All Time

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Cinema has the ability to connect with audiences in many ways. Motion pictures can make us laugh all of our problems away. They can get us to unleash our pent-up emotions and cry out all of our sorrow. They can provoke us to think, to question, to take action. Of course, they can also scare the shit out of us, and that is my focus with this list: one that I have been anticipating making my entire life. As a death metal loving teenager, I watched almost exclusively horror films for a couple of years. I was fascinated with being pushed by these gruesome images: to see how far I could go. Once I grew tired of watching the same old schlock (let’s be honest: many horror films follow the same tired formula), I branched out to all genres of cinema. However, that hunger remained. I needed to explore films that took me out of my comfort zone, challenged how I thought, and — effectively — changed me as a viewer. That lust for horror films faded, but the appreciation for provocative cinema has always stayed with me.

Of course, I still love many horror films, but I do think the genre as a whole is watered down by many lame attempts at abiding by the same guidelines: establish characters (even the most thinly written ones), create a villain (or villains), and see how much chaos can ensue (through death, paranormal activity, and other unpleasant circumstances); stuff as many jump scares as you can, and you’ve got a bonafide horror classic on your hands (rinse and repeat for the thirteen sequels that are due to come afterward). Nevertheless, this list is about celebrating great examples, not poor ones. Having said that, you will notice that this is a list of sequences, not films. Pointing out my favourite horror films felt like a decent idea (maybe one day), but to observe the moments that scare me feels far more interesting. During my horror phase (I was just a tween when it kicked off), I was indebted to one list that has sadly gone extinct online: Robert Berry’s compiled list of The 100 Scariest Movie Scenes of All Time list for the now-defunct website, Retrocrush. Here is the original 2003 list (that I first saw), as well as the 2007 revised list, retrieved via the WayBack Machine. It also introduced me to many brilliant directors and films (my love for David Lynch — which will be extremely present on this list — began at around thirteen years old thanks to this list). I hope that my list will be beneficial in this way as well.

I will be including films of all genres: as long as the scene freaked the hell out of me, I will include it. I also want to point out that the inclusion of these scenes on this list does not mean that I think the films themselves are great. A handful of the scenes below come from mediocre or outright awful films; however, what is important is that the scenes themselves are great, effective, or — of course — horrifying. In that same breath, many amazing horror films will not wind up here; I don’t necessarily find every great horror film scary (I’m also quite desensitized, for the most part), so both of James Whale’s Frankenstein films, Let the Right One In, The Witch, and many other films I outright adore won’t be here. Sometimes, an entire film can be eerie or scary to some degree, but that doesn’t mean that any particular moment had me leaping out of my seat or sick to my stomach; I can’t include all of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night on a list where a three-second-moment had me spooked, just because the former film is consistently unnerving (I can recommend the film wholeheartedly, though). These are sacrifices I’ve had to make in order to remain authentic to the original cause: scenes that stand out, and why.

Something else I will establish from now is that I will only feature films once. That’s right: I will not repeat a film at any point on this list. I have two reasons why. The silly reason why is that I think it is more interesting to have a variety of films. Of course, that seems silly when you would argue that one film can have many scary moments, and you would be correct. My more serious reason is that I feel like a film’s scariest scene almost negates its other sequences to varying degrees. If a scene stands out as the most memorable because of how horrifying they are, I personally find that the other scenes don’t scare me as much anymore. If you are trapped in a room with a rogue spider, it is scary. However, if a snake were to break in and slither around, that spider doesn’t seem so bad anymore. I will make sure to bring up honourable mentions where they apply so you can see what other scenes from a particular film I find noteworthy. I also didn’t want The Shining or The Exorcist to take up ten spots apiece on this list, so you’re welcome, I guess (both films are certainly getting featured). I hope my explanations make sense; if you remain bothered, I do apologize.

Understand that fear can be a subjective experience, so what has scared you may not have worked on me (apologies for any omissions you may come across in this way); you will soon piece together what some of my fears may be. Lastly, every entry has a written explanation; many images that I have selected are vague or unassuming (not all, mind you), so they don’t really describe what scene I have selected and why. However, as to not have blatant spoilers that can be caught via a quick glance while scrolling, I have hidden them in pop-downs for each entry. Just click on a film’s title or the downward arrow to the right of it to read more. I will warn you that there will be spoilers throughout this list, either written or via the images selected (as much as I have tried to select pictures that show the scene in question while not giving the entire scene away, I can’t guarantee that I have done a perfect job). Additionally, many of the images provided are still gory, disturbing, scary, or hard to look at for a variety of reasons, and much of what is presented here — visually or through my written descriptions — is not for the faint of heart or can be triggering. Reader discretion is strongly advised.

Enough preamble. Welcome to my creepy abode. Be sure to bring extra underwear, and enter. Watch your step, for there are many wrong turns ahead.

-

Towards the end of Black Swan, Nina goes to find the ballerina she ultimately replaced: the hospitalized Beth. The conversation goes poorly, and Beth begins to stab herself in the face: a shocking hallucination right off the bat. The cherry on top — so to speak — is Beth transforming into another version of Nina, who actually enjoys stabbing herself, it seems. The cherry on top of that cherry? Nina may have killed more than Beth’s career: she may have actually killed Beth herself. We’ll never truly know.

-

Hiroshi Teshigahara’s The Face of Another toys with the uncanny image of a blank face due to the film’s concept of its protagonist donning a realistic mask to hide his permanently destroyed visage. With the film’s constant uneasiness, a pivotal moment involving our main character being swarmed by a sea of “faceless” people burns itself into your mind instantly.

-

I have this iconic moment — one which will blow your mind — this low mainly because I find the scene less scary than I think it is kind of badass. However, I do view the infamous head explosion sequence in Scanners to be a strong indication of what David Cronenberg was capable of at a young age: with the viewer arrested by the mystery of what could happen before doubling down on the gore of what will happen; we hadn’t even seen Cronenberg’s final form.

-

The best — and creepiest — adaptation of Lewis Caroll’s Alice in Wonderland, Jan Švankmajer’s Alice is oddly comforting despite its frequent eeriness. Then comes the part where Alice becomes a doll, is attacked by a mob (including an excessively mean White Rabbit), and subsequently dunked into milk; the whole scene is impressively uncomfortable to watch, and indicative of the bold artistry of Czech cinema.

-

It may seem strange to not include another scene from The Ring, but I feel like much of the film’s strength falls on the believability of the central tape that kills its viewers seven days after watching it. The visuals on this tape are impressively haunting: like an avant-garde film from the depths of hell. I remember — and am enthralled — by the first showing of the haunted tape’s recording far more than the film that houses it.

-

I think Jordan Peele’s Get Out is an exquisite horror film, but one that more unsettling and powerful than outright scary. Well, outside of the central sequence when Andre gets his photo taken with the flash going off. His nose bleeds, his pupils dilate, and he snaps out of his hypnotic state, shouting the film’s titular message. It is a devastating cry for help that is equally terrifying.

-

Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpiece, Vertigo, kicks off with an uneasy image of an officer falling to their death. The film toys with its uncertainty and discomfort for the majority of its runtime, but it never truly gets horrifying until its climactic scene: one that eases you into a false sense of security until a blink-and-you-miss-it repetition of events (a death from the bell tower that is so swift that you are left breathless and helpless even long after the film is done).

-

Nicolas Winding Refn’s The Neon Demon is outwardly disturbing for most of its runtime (we can’t exactly forget about the necropheliac scene, can we), but it really takes the cake during its ending sequence: one where two models are ill during a photoshoot; we quickly discover that they have eaten protagonist Jesse, as her eyeball is vomited out by Gigi. Gigi proceeds to kill herself by trying to cut her stomach open to rid herself of Jesse’s body parts that she has eaten, but her fellow model — Sarah — sees this as an opportunity to eat more of Jesse. This concluding scene is diabolically twisted and gross to the point of being horrifying.

-

While it’s hard to call Tim Burton’s debut, Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, completely a family film, it certainly plays along with being an all-ages affair. Then comes the surprising Large Marge sequence, where the title character hitches a ride with a truck driver. She turns to Pee-wee to tell him what the victim of an unfortunate accident looked like, and we have a stop-motion-animated jump scare that is sure to frighten anyone (who expects this in a film like this?). Finding out the truck driver is the spirit of the deceased character of that ghost story is an extra layer of spooky, but the real horror comes from that face, the worst one I ever seen.

-

I believe many of us have seen the viral clip of this stunning example of early movie magic from William McGann’s Sh! The Octopus: a transmogrification sequence that happens before your very eyes (thanks to intricate makeup, camera filters, and precise lighting). What makes this transformation scarier is how unexpected it is in context: you see, Sh! The Octopus is not a straight up horror film but, rather, a comedic mystery one. Not only is this sequence ahead of its time, it stands out as unexpected within its own film (I cannot imagine how many theatre seats needed to be cleaned back in 1937 after this shot).

-

The concluding sequence where Adrien/Alexia is giving birth to her car-human hybrid infant is both shocking and heartbreaking. As Adrien/Alexia’s body is destroying itself to the point of their death, Titane is as body horror as the genre gets. When father figure Vincent cradles her newborn next to her now lifeless corpse, we are left with the dread ahead: a cruel world without guidance (thank God Vincent is there to save the day once again).

-

Dario Argento’s magnificent gialo classic, Deep Red, is artistically spellbinding; it is the most restrained and mature of his classic slashers. He saves the big turns for the end, including killer Martha’s karmic demise: one where her necklace gets stuck in the bars of an elevator. Once the elevator arrives, her necklace pulls through her neck and cuts her head off; the lasting image of the necklace being held in the air — free of any neck — is gorgeously disturbing.

-

I’ll be honest. I have heavily grown out of the Saw series, which just feels like futile attempts at getting more and more edgy with each trap. However, one moment that will always stand out in my head is the needle pit trap in Saw II. When a key is hidden in a pile of dirty, used needles, character Amanda is tossed in there to sift through them. We see needles stick inside of her, and hear the glass breaking underneath her. It says a lot that no other trap — no matter how creative or twisted they got — could ever outshine the simple needle pit concept; sometimes, less is more. I have hated needles ever since.

-

A criminally underrated scene and film, the “synthetic flesh” scene from Doctor X is another example of marvelous movie magic (this time we are in the pre-Code era, so you know this film goes hard). When Dr. Wells transforms himself into the Moon Killer, you get a shocking transition via what appears to be the stripping off of flesh; it isn’t quite that gruesome, but, for a film from this era, it’s shocking enough; I think the effect holds up, and I’d argue the dated look of the film adds to the uncanny feeling of watching someone’s skin literally crawl before your very eyes.

-

Enter the Void is expertly composed. We have the most memorable opening credits of all time (on a big screen, they may drive you insane or make you feel sick); you feel uneasy for the rest of the film. Despite the other scares or tense moments, this all leads up to the highly surprising car accident sequence: one that comes out of nowhere, and where you are watching from the back seat as if you are actually in the car. No one ever sees this scene coming, and no one exits it the same ever again. I feel like many films have a bit of a trust factor with their audiences that director Gaspar Noé effectively decimates here.

-

To be fair, much of the Canadian horror classic, Martyrs, is scary, but I had to pick the moment where Lucie — after slaughtering an entire family out of revenge — is attacked by a female demonic figure who doesn’t resemble anything from our reality; this breaks the film in a most uncomfortable way (I don’t think anyone expects this kind of creature, here). When the female demon slashes Lucie’s back, Martyrs exhibits an unspeakable sense of helplessness, ringing the film’s themes of trauma as loud as possible.

-

Part of me feels like Shinya Tsukamoto’s cult classic should be ranked higher, but I also find Tetsuo: The Iron Man so insane that it’s almost absurdly comedic and fascinating. I feel like the subway sequence early on sets the tone for the film incredibly well; the unnamed title character is attacked by a metallic woman with tentacle-like appendages. This image is indescribable, but, the audience will shortly realize, most of Tetsuo is.

-

Much of Jonathan Demme’s magnum opus, The Silence of the Lambs, is noteworthy; I’d like to shoutout the climactic shootout, flying moths, night vision goggles and all (an honourable mention here). Instead, I will go with the sequence where Hannibal Lector seduces a guard towards his cell, murders him, and then — the coup de grâce — turns him into a disemboweled, skin angel. It is extra scary because — for a split second — we find visual beauty in Lector’s art, as if we are on the same page as a psychopath; once our eyes adjust, we recognize how disturbing this crime scene truly is.

-

Maya Deren and Alexandr Hackenschmied’s avant-garde masterwork is only fourteen minutes long, but every frame is as memorable and impactful as cinema gets. This includes the final sequence where a nameless woman (Deren), at the end of her rope after entering and exiting a nightmare time and time again, attacks a strange man (Hackenschmied); his face smashes like a mirror, with an eerie reflection. This leads to the aftermath: the woman dead and with her throat slashed; her lifeless gaze points upward (even in death, she is wide awake).

-

I’ll be honest. I find M. Night Shyamalan’s Signs to be quite an annoying, illogical, and mediocre film. However, I have to give credit to the “birthday party” sequence. We don’t see the aliens for the entire film up until this point, and we are waiting to see what they look like. The suspense builds in this moment, as we watch shaky, distorted footage in anticipation. Suddenly, the alien being darts out; it is gone seconds later. It’s a confirmation of our worst suspicions, and a bright spot of a moment in an otherwise frustrating film.

-

Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance plays into absurdity quite frequently, but it goes so beyond comprehension when both halves of the same person — Elisabeth and Sue — fuse into one abomination: Elisasue. This being is so over-the-top that I feel like the dark comedy of the film dissipates; I’m laughing out of audacity and fear by this point (I think the eventual geyser of blood doesn’t help matters). My heart breaks for this character as well, seeing as their desperation and addiction to fame has led to their hideous demise.

-

There is a level of vulnerability and fragility throughout David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers; the topic of gynecology is highly sensitive. When one of the twin doctors loses his mind and aims to utilize new gynecological tools, the devices themselves are highly unsettling; he wants to use those where? When Dr. Beverly ignores any caution and proceeds with these tools, the end result is a bloody, nauseating affair; and normal surgical devices were already creepy enough.

-

Throughout Roman Polanski’s breakthrough film, Repulsion, Carol has a reoccuring nightmare of a hallway; it gets progressively more and more invasive, akin to the film’s themes of objectification. Towards the end of the film, this passage is now a tunnel of hands; at Carol’s most delusional state, the film is already tense, but this image is one that is full of doom and dread; we actually have to walk through this hallway from hell?

-

Yorgos Lanthimos’ breakthrough film, Dogtooth, is permanently disturbed. As we watch a horrific family dynamic (one where adult children are forbidden access to life outside of their home and are unbelievably stunted mentally), all of Dogtooth is an uneasy, chaotic watch. This climaxes with a scene where one of the daughters is under the delirious belief that one should shed their “dog teeth” in order to be mature and exit to the real world. She smashes her face repeatedly with a dumbbell and her crooked, broken smile of jubilation is somehow even more terrifying than the act that led to it.

-

Much of Paul Anderson’s science fiction film is memorably disturbing; its brand of sci-fi horror is special, should you be as perverse as I am. What stands out to me the most is a montage from another dimension: a glimpse of this film’s depiction of hell full of tortured beings, indescribable devices, and enough unimaginable sights in a short sequence to make you feel like you have gone insane. This sequence has always stuck with me; despite not being a religious man, I want to avoid this damnation at any cost.

-

Japanese cult classic House — or Hausu — is rife with ridiculous images that I feel like are a smorgasbord to eat through; once scene is guaranteed to stick out and make you feel off, even if another viewer disagrees. For me, this moment is near the beginning: the well shot with Mac’s moving, decapitated head. Even with the dated effects, this scene feels stripped from another dimension to me, and acts as a red flag early on for how insane House is going to get (if you cannot handle this scene, maybe think about continuing onward).

-

Singer Skye Riley is driven to insanity by the curse that drives the Smile franchise, During the film’s third act, she winds up in a retreat and is visited by her mother and manager, Elizabeth Riley. Skye vows to leave to protect herself and her mother, but Elizabeth begins to smile (which, as we all know, is bad news in this series). Elizabeth begins to stab herself Black Swan style, but Smile 2 — while not being as strong of a film — goes the extra mile with an extra bloody affair; a revelation that Skye has — seemingly — murdered her own mother during a psychotic episode. It’s unfortunate that Smile 2 doesn’t quite stick the landing, because it is a great horror film for the most part (particularly leading up to this brutal moment).

-

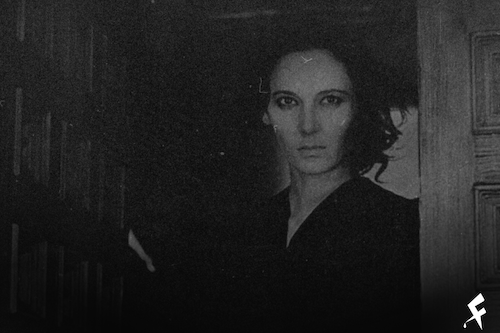

I’ll never forget watching Black Narcissus for the first time; I was sold on the fact that this was a psychological melodrama, and a significant portion of the film didn’t convey that genre at all. Boy, was I wrong. The film plummets into darkness rather quickly in its third act, climaxing with a shocking image of Sister Ruth — in a complete stage of madness — wanting to kill Sister Clodagh on a rooftop; the music swells like the sounds of demons from hell. Ruth’s fall from the high cliff, Clodagh’s disturbed gaze, and the bell ringing throughout make this moment all the more haunting.

-

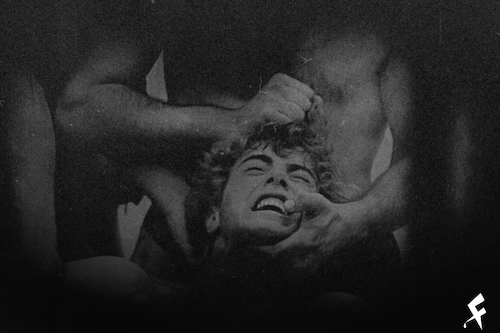

Dario Argento’s films are not exactly known for being kind to female characters, and his breakthrough gialo classic, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, exhibits this lack of sensitivity. As a mysterious serial killer goes around town killing women, one such victim is attacked right before bedtime; the scene is shot and framed to look far more than just a murder (if anything, this feels more like an act of sexual violence). Argento is known for his stylish slasher sequences, but this scene is all the more sinister because of its twisted sexual angle that turns an already disturbing scene all the more unforgivably ominous.

-

I will die on the hill that Wait Until Dark is one of the most underrated thrillers of all time. When you think of sixties cinema, not many motion pictures stand out as being authentically terrifying. However, when the blind Susy is having a standoff with criminal Roat, the entire sequence is a masterclass in suspenseful, chilling cinema; from Roat being doused in gasoline and Susy threatening him with lit matches, to Susy operating in complete darkness while Roat tries to outsmart her (using the refrigerator’s inside light, for instance), Wait Until Dark becomes a perpetual panic attack.

-

It goes without saying that Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is a beloved New Hollywood horror classic, and you are probably hyper-familiar with what scene I am going to bring up: the chum moment. Brody is dropping shark bait in the water and discussing the particulates of their mission (to capture the elusive, murderous great white shark) when the fish in question jumps out of the water and almost swallows Brody. It has been brought up how clever it was to not show the shark clearly until this very scene (to be fair, this was partially due to how mechanical the shark looked, and Spielberg wanted to hide this flaw). However, given how effective this sequence is for every viewer, some films and scenes are frequently discussed for a reason.

-

This spelunking nightmare is always unnerving, but mainly because the act of cave exploration is such a dark and dangerous one to begin with. With an awful accident to kick off The Descent, you are left feeling uncertain for most of this film anyway, but the majority of what you experience is rooted in reality. Once we get our first true glimpse at a crawler (a golem-like dweller), we are caught off guard: those movements in the dark were not tricks of our minds. Suddenly, The Descent becomes a whole new ball game, and the sense of doom that permeates throughout the film feels impossible to muster.

-

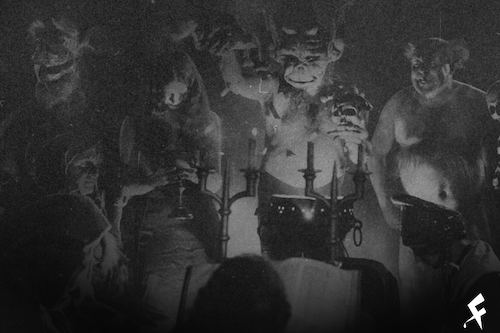

Häxan is a game changer regarding what a documentary can be; with its extensive, chilling narrative passages used to drive home points of witchcraft throughout the course of history, this film leans more towards being an anthological horror film than an outright essay picture. A highlight is a “reenactment” of a sabbath, involving Satan, a demonic feast, and children and a cauldron (I needn’t say more). Häxan is revered for its understanding of how witch hunts have stemmed from undiagnosed mental disorders and societal misogyny, but it is also acknowledged for its demented sequences, rendering the film a little too perfect (in more than one way) for fright night.

-

Health class should have shown David Lynch’s Eraserhead in place of any corny educational videos if teachers wanted to get students serious about parenthood. The creepy baby is a test of patience and courage throughout the midnight classic, but it is when it gets sick and is dying that Eraserhead dials things up to eleven; once its swaddle is cut open and its insides collapse and are exposed, there is no turning back. That baby’s cries are forever drilled into the core of my mind.

-

Michael Haneke cleverly introduces the concept of a simple golf ball in his sadistic satire, Funny Games; one of the two home invaders discusses how he has one with him while he and his partner torture a family. The third act of Funny Games sees our two psychotic bullies bolt, and our protagonists — the husband and wife — try to free one another and figure out what to do next. For a long period of time, this looks like the outro to a horrific incident, and as though the coast is clear. When that golf ball bounces and rolls into frame, my heart and stomach sank faster than an anvil in the pacific ocean: the games are only beginning.

-

There isn’t anything particularly disturbing narratively about this portion of the second chapter of Kwaidan, but I feel like this sequence — where the snow woman (or yuki-onna) debates between killing Minokichi or leaving him alive and alone — is unsettling for other reasons. I think that director Masaki Kobayashi is phenomenal at merging the faint connection to reality that dreams and silent pictures have, making a converged effort to depict a broken heart via a snowstorm, surreal imagery, and a damning score; this is as creepy as breakups get in ghost stories.

-

Wes Craven made it scary to go to sleep with his slasher classic, A Nightmare on Elm Street; who would want to get killed by Freddy Kreuger in their dreams? However, the biggest scare of the film goes to the moment where Glen is sucked into his bed with his blood spilling all over the ceiling; what a stunning shot conceptually. When the line between being awake and asleep is blurred like this, we aren’t even safe being tired anymore; we could be murdered when we are just on the cusp of dreaming. This scene is the worst for anyone who deals with sleep paralysis demons.

-

When we see a villain fall and the world around them celebrates, we tag along and cheer. However, Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man places us and Sgt. Howie on the recieving end of this mass hysteria. As Howie is shoved into the wicker man behemoth with sacrificial animals and set aflame, the villagers all sing and dance; to them, this is jubilation; to us, this is hell. The fact that this scene feels so disturbing while taking place during the daylight and without employing many tricks makes The Wicker Man even scarier to me; how did they figure out this sequence without playing by any of horror’s main rules?

-

Canadian cinema was in a strange place in the nineties, where arthouse sensibilities became tropes for a new wave of horror. Vincenzo Natali’s Cube was like Saw before Saw (and, quite frankly, much better). As our characters navigate trap-filled rooms and lairs, we never quite know what to expect. This includes the moment where an unsuspecting room actually releases a spring trap of grid-like piano wire, which slices straight through a character and dices him up into pieces; I’d sooner acknowledge the irony of the cube effectively turning someone into meat cubes, but the moment is just so jarring and surprising when it happens that it feels oddly insensitive (as if this was a real death, despite how clearly fantastical the sequence and film are).

-

Perhaps the greatest adaptation of an Edgar Allen Poe work, Jean Epstein’s The Fall of the House of Usher is a fantastic silent horror film (I do find silent pictures to be inherently spooky as well; perhaps it is the lack of diegetic sound and the choppy frame rate that makes a film feel unfamiliar and uncomfortable for me when used effectively). When the central castle burns down (I suppose the title gives it away, doesn’t it), Epstein effectively merges the flicker of flames with ghostly apparitions, creating a sequence that is almost mesmerizing. We are forever trying to believe what our eyes are telling us. The end result is — in all senses of the word — haunting.

-

Some horror films are defined by special moments. I don’t think Insidious is a strong film overall, but I cannot deny the effectiveness of its most popular scene. As Lorraine details a nightmare that she has had, we are tossed back-and-forth between her discussion at the table and the story itself. We are fully prepared for a jump scare to occur in the shots of Lorraine’s story, but when the foretold demon winds up behind Josh, we get the fright of our lives. I cannot fault horror fiends for championing at least this sequence.

-

You can point out many moments in David Cronenberg’s The Fly, but the scariest scene for me is one that doesn’t deal with body horror all that much (at least not within the confines of the genre’s tropes). It’s during the arm wrestle showdown between Seth Brundle — who is now a superhuman with fly-like capabilities — and a random tough guy at a bar. The tension builds as these two macho men put up a strong fight. I think most of us predicted that Seth would win. No one can foresee the competitor’s wrist snapping in half, with his bone skewered out of his flesh; as Seth celebrates as if nothing happened, all we can do is curl in fear.

-

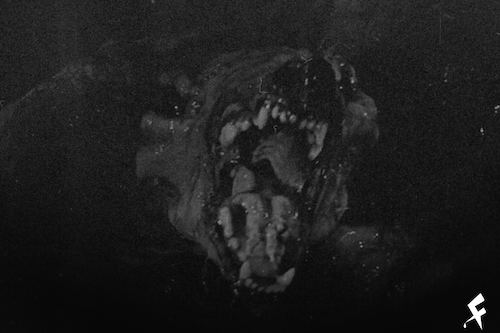

We know things are getting stranger the deeper into the shimmer we go in Alex Garland’s magnum opus, Annihilation. When animals and nature start converging bit by bit, we lose sense of normalcy. When a half-mutilated bear — with the cries of the now-deceased Cassie refracted into the beast’s roar — starts circling our expedition of sacrificial lambs, it is impossible to pinpoint what this scene feels like to watch; Garland plays with this miasma for long enough, before the scene turns into an anxious bloodbath of an action scene (this “release” doesn’t stop the sequence from being viscerally unsettling).

-

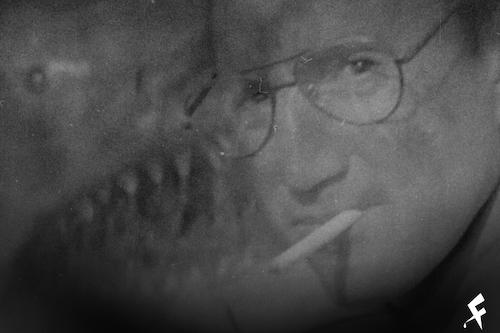

This scene is a rare one, and I will explain how. When you first watch David Lynch’s Lost Highway, you reach the party sequence where lead character Fred is approached by a pale stranger who claims that the two have met before; in fact, the man promises that he is at Fred’s house at this very moment and implores the latter to call his house phone to prove it; we learn this is true. This dialed-down scene is already eerie enough, thanks to Lynch’s expert use of sound, awkward pauses, and minimalism. What makes this scene even stronger is how much scarier it is on subsequent watches when you learn more about how such a “trick” is even possible; it’s also as if Lynch is commenting on how films can be revisited in the day and age of physical media, and he wanted to ensure that scary moments don’t lose their power when a film is rewatched; mission accomplished.

-

There is a remarkable time during the silent era when the efforts of filmmakers and artists to make visions come to life on the big screen went from noble and shaky to shockingly good. This was just as noteworthy in the horror genre, where some illusions and achievements still hold up to this day (so you can only imagine how screwed up patrons would have felt over one hundred years ago). Case in point: The Golem: How He Came into the World, and — specifically — the summoning of the Great Duke of Hell, Astaroth. Astaroth is massive and unpleasant to look at, and The Golem does a great job of cloaking him in darkness and with the right camera angle and distance to make this birth feel like we are seconds away from an eternal curse ourselves.

-

Guillermo del Toro’s masterpiece has us following little Ofelia through a series of trials during the Fancoist era of Spain. Her understanding of the horrors around her get channeled via a fantasy world of oddities, including an epic feast that the poor, hungry child cannot refuse despite the strict instructions to not eat anything. She eats two grapes, which awakens a “Pale Man” who inserts eyeballs into his hands, looks around, and finds the child and the fairies accompanying her to feast upon. He snarls, chases after them, and succeeds as much as Ofelia does; she has two small grapes, and he has two small fairies as a snack.

-

Roman Polanski’s Chinatown is as bleak as neo-noir gets. Earlier in the film, Evelyn Mulwray rests on her car’s steering wheel out of exhaustion, only to be startled when she accidentally presses the horn and shocks herself back upright. This prelude becomes fully realized during the cataclysmic climax, when cops are firing after Evelyn as she is fleeing by car. Suddenly, we hear a loud, sustained car horn and fear what has just happened. The car door is opened, and she spills out with a gaping hole in her eye socket and completely void of life. Her daughter (and sister) accompanying her is distraught and screaming; Evelyn’s father — and her assaulter — feels partially bad while whisking her daughter away, both never to be seen again. We are left dumbfounded and speechless like J. J. Gittes, only to be left out in the cold after one of the darkest and most terrifying endings in cinematic history.

-

Director Michael Haneke is known for his challenging and disturbing films, but his masterwork — Amour — is a devastating romantic drama. Even here, he sneaks in the opportunity to be disturbing. Character Georges is struggling to take care of his wife, Anne, as her health worsens after suffering a stroke and an unsuccessful surgery. At one point, Georges is finally able to rest and is in the middle of a dream. However, this dream quickly turns sour as he is wading through water and hidden in darkness. When he is swiftly suffocated by an unknown hand that grasps his mouth from the depths of the shadows, he jolts himself awake and we leap out of our seats.

-

I admit that it is tough to select the scariest scene in John Carpenter’s classic, The Thing, because there is a lot going on and many creepy sights to lose your shit over. I ultimately went with the transmogrification of the sled dog early in the film for a couple of reasons. First, this is a red flag as to what is to come, and we get shown so much in terms of body horror that whatever transpires may be technically worse but similar enough that I still feel like this first instance is the strongest. Secondly, I will always have a soft spot for animals, and seeing a lovable friend turn rogue because of this parasite (of sorts) alerts us that any similar actions from this point on are inherent and not the conscious actions of immoral people. This sequence sets the stage and keeps us in the dark at the same time.

-

We are a portion of the way through Ridley Scott’s Alien when the trip our team of astronauts are on is “accomplished”. It’s time for a celebratory meal before going back to sleep for the long journey back. After a bit of a scare involving some random “egg” looking sack earlier, Kane isn’t feeling too hot but comes to his senses and partakes in the dinner. Seemingly out of nowhere, Kane feels sick again but his symptoms are far worse. Suddenly, a baby alien — now crowned the name of “chest burster” — does exactly what its namesake suggests. This scene is an example of a jump scare done methodically and with a purpose, but we also get two sets of bad news at once: Kane is dead, and now there is a rogue alien on board the Nostromo.

-

Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin gives us as little information as possible, in teensy chunks so we can follow along and fall prey to the film’s darkest secrets. Yet another guy wants to score with a nameless woman (we learn she is an alien in human skin with a mission to lure people into a trap so their flesh can be harvested and used). This time, we see what happens to the woman’s victims. This “date” creeps into a void that is like a thick jello and spots a fellow victim who is long dead and definitely naked. As we are frozen in a stasis with these two poor souls, the organs of the dead prey are sucked out in an instance, with the only sound being a loud and sharp cymbal blaring. His skin hangs suspended like a flag in the wind; we cannot believe our eyes once our hearts stop racing.

-

Charles Laughton’s lone film as a director is stuffed with unforgettable and haunting images. My pick for the eeriest scene in The Night of the Hunter has to be Willa’s aqua-burial. She is murdered by her psychotic preacher husband, Harry Powell (who is actually a serial killer looking for a large sum of money and has married Willa after her late husband — who knows where the money is stashed — passes). If killing Willa wasn’t enough, Harry ties her to a car and plunges it into a nearby river; the image of Willa in a watery limbo is beautiful yet mortifying.

-

Many scenes can be included here from The Phantom Carriage, including the shot of David driving an axe through a door which heavily inspired the “Here’s Johnny!” scene from The Shining. I nominate the first time we see the titular vessel of death in the film (and, believe me, we see it or the likes of it quite a bit throughout the film). The way the carriage is made and the overlay effect are sublime to the point of sending shivers down my spine, and I believe that the film’s age only adds to the spookiness of this image.

-

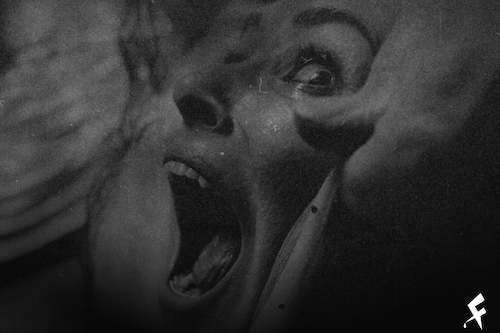

Dario Argento’s original Suspiria really sets the mood right with a neon-coloured nightmare that is so ridiculous and over-the-top that it somehow feels even more real. A supernatural force antagonizes two students at a dance school in the middle of the night, but we can’t even tell who or what he is (from having cat eyes that peer through the dark and a massive, manly arm that breaks through a window and starts smothering the student’s face against the glass). He continues to stab that student directly through the heart (beating and all) before she falls through the ceiling light below; she doesn’t make it to the floor, mind you, seeing as the cord of the fixture hangs her on the way down instead. Oh, and the massive shards of glass from this scene slice through her classmate’s head and pin her dead corpse to the floor. With Goblin’s tribal sounds from hell serving as the score, this iconic opening is extreme in every way.

-

Vampyr is indebted to the silent era and aims to evoke the eerie spells of that generation’s horror films with minimalist forms of fear. Such an example is when character Allan Gray hallucinates that he can see his own body in a casket and awaiting burial. Is he essentially being buried alive, or is he dead and no longer a part of the living? The scene is quite basic but director Carl Theodor Dreyer is so good at making every second count in Vampyr. What could have just been a bit of an ambiguous moment to make you feel uneasy winds up becoming a vessel of panic and dread.

-

Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers was never meant to be an easy watch, given its themes of illness, death, and familial divergence. As difficult as the whole film can be to grapple with, Karin’s dinner scene has to be the most traumatizing. Glass breaks and Karin — who has become existentially despondent — uses the opportunity to take one of the shards of glass and pierce her genitals with; she then smears the blood of the wound on her face and lips. In a film full of unspoken secrets and mortifying revelations in the face of grief, Karin’s candid moment is one that will have you squirming and recoiling.

-

By the end of Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse, we — and the characters within the titular structure — have gone insane from cabin fever and internalized rage. Thomas Howard — using the identity of Ephraim WInslow, who he didn’t save from drowning — has now killed fellow wickie Thomas Wake and climbs the lighthouse to reach salvation. He opens the lighthouse’s lens in the lantern room and goes blind, becomes slowly incinerated, and is so delirious that he howls. We don’t even see how he makes it out of the lighthouse but outside on the rocks, he is being pecked to death by angry seagulls Promethean style. This is peak cinematic madness.

-

Bob — given a deceptively simple moniker — has become one of the most revered villains in all of pop culture thanks to his appearance in all things Twin Peaks. Naturally, he returns in the film, Fire Walk with Me, to haunt poor Laura Palmer and all of those around her. The slow motion shot of Bob hopping over the couch is like something out of an awful nightmare. He could easily go around the couch, but he instead leaps over it like it’s a hurdle. He is moving so slowly that we can escape, yet we are stuck in place. David Lynch understands the illogical terror that only dreams can possess, and Fire Walk with Me — a frightening film throughout — brings these nightmares to fruition with shots like this one.

-

A top ten — maybe even five — horror film of all time, Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face is more spellbinding and chilling than it is outright scary. That is, however, outside of the central surgery sequence, where character Edna’s face is being removed so it can be used to restructure Christiane’s disfigured visage. This scene looks far too realistic, even today (let alone 1960); it’s as if we are peering into an illegal operation and cannot stop it from happening. As if you can feel every snip and peel, this face-removal procedure is sure to keep you up at night.

-

Grief is an inexplicable, life long experience. I’m not quite sure how that comes into play here, but Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now is full of mind-boggling images that simply do not make sense; even the death of John and Laura’s daughter, Christine, is shown in such a way that is cinematically gut-wrenching (as if this tragedy was a work of art). John keeps seeing a person in a red coat throughout the film; maybe he believes it is his departed child as a ghost or back from the dead. It’s actually a murderous dwarf who kills him with a meat cleaver; John has had visions throughout the entire film, and the irony here is that — even if one could predict that John was the next to die — no one could predict how John would go (as if it was an episode of The Twilight Zone straight from hell).

-

Evil exists, and evil people cannot be escaped. Many horror films make a note of letting viewers know that they are distanced from what they are seeing. George Sluizer’s The Vanishing feels possible to the point of being nauseating. We follow Rex who is in search of his missing girlfriend Saskia; he is eventually confronted by the sociopathic professor, Raymond, who confesses to kidnapping Saskia. Raymond says Rex must live through what Saskia has in order to find out her fate, Rex is stuck in a psychological dilemma. What ultimately happens is that he isn’t given a choice; his coffee was spiked, and he wakes up buried alive. No one is able to hear him. He and Saskia are gone without a trace, while Raymond lives a guilt-free life. The credits roll, and we know that there will be no justice. I must also state that being buried alive is one of my greatest fears, so seeing it done this well here garners The Vanishing extra scream points.

-

Tobe Hooper — or Steven Spielberg (depending on who you ask) — had no reason to go as hard as he did with Poltergeist. Most of the film is reasonably scary in an all-ages (well, maybe teens and older) sort of way, until “the mirror” sequence. What starts off as the act of washing one’s face after a bad vision turns into the slow act of peeling away scabs and — soon enough — full strips of flesh. Within seconds, skull and muscle appear, only for us to snap out of this hallucination and see that nothing has happened. Even so, the damage is done: who the fuck can forget a face like this?

-

There doesn’t need to be a description for this entry. You have a family film about children who have won the chance to go to a magical candy factory owned by the elusive and curious Willy Wonka. Then, out of nowhere, all of the tourists are taken for a boat ride through a dark tunnel. Gene Wilder renders Wonka a complete psychopath in this scene who drones on and gets progressively louder until he is shouting like a mad man. We also see images that are insane for a kid’s film, including a millipede crawling on someone’s face and a chicken getting decapitated. This is a horrifying scene in general, but in a film where you’d least expect it? No wonder why this scene is infamous!

-

A criminally underrated silent film, Teinosuke Kinugasa’s A Page of Madness is a complete trip to lose your mind with. A particularly spine-tingling scene is where a janitor working at the central asylum wants the inmates to be happier and he dreams of them wearing happy masks. Their “joy” is our horror: the uncanny look of this mob of plastic faces will stay with you for a long, long time.

-

Poor Sara Goldfarb is well off the deep end by the third act of Requiem for a Dream. All she wanted to do was lose some weight so she can fit in her old red dress when she appears on television. During the downfall act of the film (where all of our protagonists are going through hell), Sara is hallucinating some nightmarish shit thanks to the pills she is on. The cherry on top of this nightmare is when her refrigerator starts “crawling” towards her; it even opens up its “head” — puppet style — and vows to devour her. In hindsight, the prop looks so fake but director Darren Aronofsky does a brilliant job making this fridge actually seem threatening; as if it will kill Sara and us.

-

Where were you when you put on Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques and reached the bathtub scene? How old were you when you saw what was meant to be a corpse suddenly rise out of the water after being submerged for a lengthy amount of time, with false eyes being popped out? You may be selected for compensation after one of the most what the fuck endings of any horror film of all time: with a twist so major that Alfred Hitchcock wishes he directed Les Diaboliques.

-

I don’t have enough space to go through all of the twisted moments in Ari Aster’s Midsommar? Well, I at least want to elect the cliff ritual as the scariest scene of the film. In broad daylight — akin to The Wicker Man — we see an elderly couple partake in an ättestupa ceremony, committing suicide by falling from a cliff. One of them survives and shrieks in pain; the rest of the cultish commune howl in cacophony with him before he is put out of his misery (by — what else — a mallet to the head to finish the job). An honourable mention goes to the inferno sequence at the end of the film which was almost what I considered for Midsommar’s entry on this list.

-

I don’t think all of Jacob’s Ladder has aged well, as the “dramatic” moments of the film feel quite corny, perhaps to counter how dark this film gets. Believe me, it gets dismal. The standout sequence is the nightmare hospital one. Jacob is locked on a stretcher and is apparently having a bad dream, full of disturbed patients crowding him and acting in inexplicable ways (the muttering, the shifting, the twitching of that hooded figure at the end). This scene is brilliantly scary that makes up for many of the film’s faults; this sequence alone greatly inspired the Silent Hill video game series (a strong form of praise, considering that Silent Hill 2 is one of the greatest games ever made). I will always appreciate the boldness of this sequence.

-

Despite not actually being a horror film, the German expressionist classic, The Man Who Laughs (directed by Paul Leni) is still a deeply unsettling film. I could pick many scenes with Gwynplaine — a man who is permanently disfigured with a wide smile that he cannot close. For me, a scene where Gwynplaine is flaunted like a circus freak — with an audience guffawing at his condition — is terrifying. Part of the horror comes from how much of the scene feels like this mockery is happening to us. The sadness I feel for Gwynplaine also feeds into the anxiety and fear this sequence gives me.

-

Men Behind the Sun gets my dishonourable label of “most fucked up film I have ever seen,” which is not a good title to be crowned. I actually despise this film, but I have to give credit where it is due. One scene has stuck with me ever since I saw it decades ago: an experiment called Maruta. A prisoner of war is left in the cold and has her arms and hands frozen, burned with boiling water, and re-frozen. Once she has lost all life and sensation in her limbs, she is brought inside and has the skin off of her arms effortlessly stripped off. She screams not because she is in pain, but out of sheer fright as to how easily her body is falling apart. There are many disturbing scenes where this came from (and numerous are highly unethical and are problematic), and I do not recommend this film whatsoever; however, I needed to include what is one of the scariest scenes I have ever seen.

-

An honourable mention from mother! is one that has stuck with me ever since I saw Darren Aronofsky’s twisted allegory of Mother Earth: people getting shot point blank in the head (it just looks far too realistic for me to be able to shake it off). Otherwise, I think everyone would have to pick the notorious climax where mother’s newborn baby is paraded around away from her grasp and is then killed and feasted upon like a miniature buffet. A clear metaphor for the two-sided nature of religion (the worship and execution of Jesus Christ), this frightening image is strong enough to curse you for life.

-

The Exorcist III cannot hold a candle to the original film, but it is significantly better than the atrocity known as Exorcist II: The Heretic. It also has a handful of memorable sequences, including the hospital scene which is so shocking that it is almost as good as some of the scares in The Exorcist. We wait a few minutes in a hospital waiting to see what will happen next; the long take of seemingly nothing is meant to feel dull and unassuming to the point of distracting you with its normalcy. It is a medium wide shot of nurses doing their work. Out of nowhere, there is an extreme zoom up to a nurse nonchalantly walking with a ghostly killer right behind her, stalking her with a knife inches away from her head. It is a jump scare that will make you never want to feel at peace with meditative moments in any film.

-

Where do I begin with the Russian roulette scenes in The Deer Hunter? Of course, I can’t just select all of these sequences; I’d have an entire third of a film nominated as a scary “moment” if I did. The final showdown is heartbreaking, given how far gone Corporal Nick is. The first Russian roulette sequence is a test to see if you can muster what you are seeing so far. I’ll nominate the scene where Staff Sergeant Mike wants to orchestrate a break out of the Vietnamese POW camp they are held in during a heated, tense game of Russian roulette, where all bets are off and anything can happen. This scene is meant to be thrilling, but it winds up being far more than that when it leaves audiences shivering in their boots knowing that no one is safe.

-

Alfred Hitchcock rarely got gory with his films; if he did, he was usually artistically risky with his choices. With The Birds, he went full throttle with one shot in particular. As the bird situation is getting worse and the flying beasts are getting more unpredictable, we stumble upon Lydia’s neighbour’s house which is seemingly abandoned and with broken windows and open doors. Lydia finds her neighbour dead and eyeless: his eyes having been plucked out. The stutter-zoom towards his face sells the shot (for a film that is this old, I still cannot figure out how they made this effect look so believable). In a film full of gambles where some work and others don’t, this eyeless horror is certainly one of Hitchcock’s most effective stunts.

-

The Passion of Joan of Arc is many things; brilliantly acted, with Renée Jeanne Falconetti’s performance as one of the greatest; harrowing with its depiction of the patron saint’s trial and execution; downright terrifying at times. It may sound silly, but the moment where Joan of Arc is pierced in the arm so doctors can begin bloodletting has forever scarred me; just seeing the blood squirt out of her arm — after she has been through enough and will endure more — mortifies me. I know that bloodletting is reportedly “safe,” but that doesn’t make it any nicer to look at. Finally, keep in mind that this film is from 1928; as far as I know, the bloodletting was real, and that is Falconetti’s actual blood arcing on the big screen. Now do you feel sick?

-

At the end of Brian De Palma’s New Hollywood horror film Carrie, the title psychic teenager is now long dead after the whole prom fiasco (a bloody affair which is also worth shouting out). The only survivor of prom night is Sue, who goes to lay flowers where Carrie’s grave is marked by a crucifix “for sale” sign (let’s not forget the graffiti-tagged message for Carrie White on there: with warm wishes to burn in hell). As Sue places the flowers down, Carrie’s arm bursts out of the grave and grabs Sue. I’d rank this spicy jump scare higher if it didn’t wind up being a dream sequence that Sue wakes up from (traumatized, no less), but I do think that this Carrie moment is shocking enough to admit that it scares the bejesus out of almost anyone who watches it.

-

Another entry on a potential future list (Cannibal Holocaust certainly is one of the most fucked up films ever produced), this Italian zombie film is stuffed with many horrific scenes (tons of animal cruelty as well, just to make you feel even more sick). There’s the clever concept to have a film-within-a-film: we follow an anthropologist who is searching for a documentary crew who has gone missing within the Amazon rainforest while analyzing a cannibal tribe there. If the remainder of the film wasn’t insane enough (as we see murder after murder, human or animal), the ending is an absolute bloodbath. We discover the left over footage of the documentary crew and see that members have been beheaded, raped, and disemboweled by the tribe. While the filmmakers did a lot to provoke the tribe, this is still an unholy scene made even more difficult to stomach given that it looks real (with that documentary sheen). Don’t eat during this one, folks.

-

Ah, yes. The next to last song. Dancer in the Dark features a recently-blind mother being put on trial and eventually led to her execution (despite being innocent). She tries to turn the swirling sounds around her into the basis for a musical so that her life can be more magical than it is (which, in reality, is quite depressing). She resorts to this tactic once more when she is moments away from being hanged, and she is terrified and in dire need of some sort of comfort. However, earlier in the film, she already discusses how she leaves the theatre before musicals reach the final song because she doesn’t want these films to end in her mind. So, instead of a swan song, she hopes to sing the “next to last song”; as we are rudely informed, she doesn’t even get quite that when the film concludes with one of the most disturbing, shocking images of any film in recent memory.

-

This is another entry where one could elect many scenes that would work; Frank Booth’s first appearance could certainly qualify. I always thought that the final sequence in Dorothy’s apartment in Blue Velvet was the film’s scariest moment. Jeffrey arrives there to find a horrifying scene where a dead, gagged corpse with a sawed-off ear is not even the worst sight (I’d argue that Gordon being almost dead, standing, and resorting to arbitrary muscle twitches and reactions while half of his brains hang out takes the cake). Jeffrey agrees that this is fucked up and wants to leave, but he is cornered by Frank (in his “well-dressed man” getup) who sprints up the stairs to kill him. Jeffrey goes into hiding in the closet, and Frank arrives with his silenced pistol draped in — what else but — blue velvet. This showdown couldn’t be more perverse.

-

It may feel a little obvious to place the original Nosferatu on this list at all — let alone so high — but I do think that the frequent mention of F. W. Murnau’s horror classic is for good reason. Count Orlok is really creepy in general (yes, even in his SpongeBob SquarePants appearance), but his shadow is even more unsettling. When Count Orlok is slinking up the stairs to claim another victim, it’s bad enough how well this image works. Murnau goes one step further with the image of Orlok opening the door; with a clever camera angle and use of lighting, it appears as though Orlok’s shadow is stretching, making the vampire feel unstoppable; what transpires afterward feels hopeless by comparison.

-

My actual favourite moment of Takashi Miike’s Audition is when Asami decapitates her abuser with piano wire; it’s strangely exquisite, but also brutal. Of course, when it comes to the scariest scene, the final torture scene has to be the top candidate; there’s something about Shigeharu being paralyzed and having acupuncture needles shoved into him (oh, let’s not forget that he cannot move but he can still feel pain); this includes his eyes, which will always make me feel sick. If you watch Audition and don’t know what you are in for, the film starts off as a romantic drama, It gets dark at times, sure, but there is no way you can expect how insane the film gets, and Miike takes Audition to the next level with this eyesore (heh) of an ending.

-

In case you were wondering when a film by the Italian horror master Lucio Fulci would appear, we have reached the part of this list where his name will appear. First up is City of the Living Dead, also known as The Gates of Hell (this is how I knew the film), and what scene would I pick but the infamous “guts” one? You know, with the crying of blood, the eventual vomiting of guts and organs, and then one’s head getting squashed to a pulp with all remaining innards squeezing out? With context or without context, this scene is disastrously disturbing to the point that it heavily surpasses the film it comes from (no matter what title you know it by).

-

When I was a horror-loving teenager, I was under the misapprehension that the Hostel films were good. They are not. They are actually atrocious and mostly a waste of time; mostly. I cannot turn a blind eye to a scene that sticks with me. For years, when I grew out of these two horror films, there was one part that always made me feel sick to my stomach: the blood bath. A woman hands helplessly upside down above a bathtub; another woman with two scythes slices up the tortured soul above her, with the victim’s blood spilling all over the psychopath below. The hanging girl screams louder than ever which seems like the perfect moment for the murderer to bring out the smaller of the scythes for the final blow: a throat slash that drenches her (the dying girl tries to scream but no longer can, while the killer below rubs the former’s blood all over her). I will always be frozen by this scene because of how extreme and — admittedly — well crafted it is; throwing every idea at the wall will occasionally result in one success like this scene.

-

Welcome to Film School 101, everyone. I know the eye-cutting scene is so on-the-nose when it comes to horror film lists, but can you blame everyone who has been shaken up by a scene where — you know — a woman willingly has her eye cut open with a straight razor? Part of the reason why this isn’t even higher is that the film obviously cuts to a non-human eye, but I’d argue that seeing a dead cow’s eye getting cut open is also no picnic. The shot is so impactful that the rest of Un Chien Andalou is just as fantastic, and yet no one ever brings up anything but the eye sequence: a masterclass in cutting (both in terms of editing and, well, you know).

-

All of David Cronenberg’s film, Crash, is shocking, but I must tip my hat to a scene that is terrifying without using any conventional methods to scare audiences. At the very end, Catherine wants to achieve the ultimate pleasure by dying in a car accident (if you have read this far without seeing Crash, please watch it first before judging me here). Her car flies and flips off of he road. Her partner, James, runs to her side and sees if she is okay. It’s bad enough that they start having sex amidst the vehicular ruins, but this is no surprise if you have reached the ending of Crash (a film that is all about this fetish). What gets me is the disappointment expressed by both of them, as James says the film’s haunting final line: “Maybe the next one.” I cannot express how chilling it is that they are upset that she didn’t die, and the depravity found in someone wanting to achieve the ultimate orgasm via their loved one literally getting killed. I feel like I am stuck in an alternate reality, and I am begging to be released; fortunately, the end credits are just around the corner.

-

“What? How is the shower sequence in Psycho not ranked first?” Well, dear reader, I think that Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho scene is an exemplary benchmark for its time, but I also feel like it feels a little subdued by today’s standards (don’t blame the film, blame society, I suppose). I think the shower scene works as well as it does today because it is so expertly assembled; from the slow zoom outside of the shower to a shadowy figure, to the quick cuts and extreme close ups during the actual slaughter (let’s not forget the audacity of having who appeared to be the main protagonist die early in a film and not come back in any way). I will always respect and love the shower scene in Psycho, and I still think it is quite a scary scene (especially during that first watch), but I also think some films have surpassed how frightening it is since (I do, however, think this is a prime example of how well a scene can be assembled, horror or not).

-

Of the contemporary masters of horror, I think Robert Eggers has had the better filmography. Having said that, Ari Aster can claim the scariest scene of his peers, found in his feature debut, Hereditary. When Peter is driving his sister, Charlie, to the hospital because of an allergy attack, he is also under the influence. He panics when there is a dead deer in the road and swerves; meanwhile, Charlie has her head out of the window, trying to get some air as she chokes. Peter accidentally kills his sister by decapitating her when she connects with a telephone pole: a sound and sight you’ll never forget. This is bad enough, but the glacial scene afterward — where Peter drives home, stunned, and awaits his family’s reaction — sets up the coup de grâce: a close up of Charlie’s severed, mashed, maggot-filled head while her mother screams in agony.

-

Gaspar Noé’s sophomore film, Irréversible, plays — well — in reverse. Without much context, we get a climactic scene early, and it involves a mortifying image of someone getting their face mashed in with the bottom of a fire extinguisher; this shot doesn’t cut away, looks far too real, and has other disorienting factors as well (including the score by Daft Punk’s Thomas Bangalter, which contains a frequency that is meant to make you feel nauseated while watching). Much of the rest of the film will feel uneasy after this offensive display (I won’t even go into the notorious subway scene which I considered placing here, but I find it less scary and more outwardly exploitive, upsetting, and sickening).

-

I considered placing the iconic "eyes” ending of Rosemary’s Baby on this list because the scene is so good at scaring you with as little information and imagery as possible. However, when I think of the part of Rosemary’s Baby that makes me the most petrified, it must be when the title character is — there’s no easier way of saying this — is raped by Satan. This is shown with a strange dream, cult imagery, and other uncomfortable factors. It’s already an unpleasant scene when you first see the film and don’t know what is happening, but when you know that this is when the demon child is conceived, this “hallucination” becomes a complete nightmare.

-

I consider Berlin Alexanderplatz a film (it’s just one that is fifteen hours long and divided into parts), so I will include a major portion of the film’s epilogue here. For thirteen hours, we are lulled into a melodramatic, period-appropriate Berlin in the late twenties. Much of the picture is Franz Biberkopf trying to atone for his sins and become a better person (despite failing). The epilogue abandons all of the tradition of what has come before it; it is already unsettling thanks to its unorthodox anachronisms. That’s when the film places you in what I consider the scariest depiction of hell ever put to screen, including the act of being repeatedly run over by a car, humans being massacred in a slaughterhouse, and the literal bombing of heaven. This lengthy, unforgiving sequence is already a lot to handle, but I think placing it after thirteen hours of something else will decimate any viewer after being tricked by normalcy for so long; I recall the feeling as if I was going insane when I first arrived at this dungeon of agony.

-

It’s not worth setting up anything for this entry because Inland Empire is easily David Lynch’s most indecipherable film. Even so, much of the motion picture is watching Laura Dern’s character (be she Nikki or Sue) go through devastation and torture. The film is shot via a hand-held camcorder, so the three-hour experimental epic is sure to make you feel disoriented. Towards the end, we are “graced” with an awful jump scare: Nikki’s distorted face, which then turns into a mug oozing blood. Out of context, these images actually look rudimentary and almost silly, but it’s the way Lynch enhances these shots with superb sound editing and eerie buildups that make them work; I’d also argue that their unprofessional look adds to the uncanny, unfamiliar feeling they evoke, rendering this flash of pain even more alarming.

-

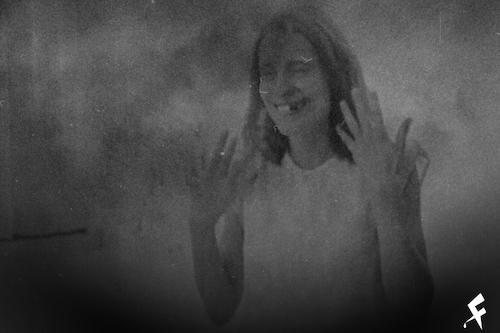

Possession being featured here is indebted to Isabelle Adjani, who boasts the greatest horror performance of all time (in case this list didn’t make it clear, even with my firm stance on how unreliable the genre can be, horror does possess many exemplary performances, so this claim is a major one from me). Adjani is completely devoted in this psychological, hyperbolic horror film, and the classic subway scene is proof of this (and, also, the most effective scene of the entire film). Adjani’s performance represents two tragedies during this scene: a woman who is miscarrying, and a person being possessed. She shrieks in pain, slams herself into the hardened subway walls and floor, and has a meltdown that is as vulnerable as acting gets. Once she starts gushing blood and a milky mucuous-like fluid out of all of her orifices, the panic begins to set in: we don’t know the extent of what is going on, but all is unwell, here (and we begin to worry about how much worse it will all get).

-

The entirety of Tod Browning’s Freaks is unsettling. The film’s focus on people with conditions that have rendered them lives of exploitable sideshow “attractions” is heartbreaking enough, but knowing that a majority of the cast here have actually lived these lives is even sadder. Then, there’s the plot with Cleopatra, who secretly wants to use these new “friends” for her own purpose. At first, she is welcomed into the family with the eerie “one of us” chant (a scene that many find petrifying in and of itself). Once the others learn of Cleopatra’s true motives, she is eventually captured and “transformed” into an exhibit herself: the “human duck.” Cleopatra squawks and fidgets in a way that knocks the wind out of me. In the end, Cleopatra was only one of “them” because she is now a circus act, rejected and judged by society; however, she will be even lonelier without the other outcasts. What an unsightly ending.

-

This wouldn’t be a proper horror list without at least another Lucio Fulci film. The Italian horror director is known for making not-so-great horror films that possess one or two standout scenes that will scar you for life. Case in point: this scene from Zombi 2. I have a fear of eyes being hurt, pierced, or hurt, so the moment where Paola is hiding in a house with a rogue zombie has cursed my mind for decades. Paola holds a door shut, which the zombie bursts their arm through. They grab of Paola’s head and start tugging it towards a massive splinter that is heading right towards her eye. If the film cut away from the impact, it would already be far too disturbing for the average viewer. The fact that Zombi 2 shows the shard go into Paola’s eye, get lodged into her head, and then proceed to break off from the door is a certain level of hell that is not for the faint of heart (Fulci is one sick dog).

-

A horrific moment doesn’t have to have monsters, paranormal activity, or the unknown to work. It doesn’t even need musical cues, a tense score, or dynamic editing to build up to a payoff. Look no further than Michael Haneke’s Caché. The film goads viewers into thinking that the stalker sending our protagonists Georges and Anne these uncomfortable video tapes (and other forms of abuse) is Majid, who rejects these accusations. Eventually, Majid agree to meet and talk with Georges and invites him to his apartment. The film coaxes you into thinking that the end of the story is near, and that we are working our way towards a conclusion. Instead, Majid cuts his own throat open with a box cotter. The shot is still and continuous. There’s no form of a clue as to what will happen. The sequence is actually fluid to the point that it almost feels natural and comfortable: a tone that may leave you very little time to process what you have just seen. This is a filthy trick by Haneke, who leads us to this unpredictable image of finality.

-

There are roughly a dozen scenes from William Friedkin’s The Exorcist that would work here, and I cannot judge anyone for selecting another moment (here’s a potential hot take: my honourable mention here is Regan’s spinal tap procedure, which freaks me out far more than the pea-soup vomit or head-turning scenes; not sure what this says about me). The moment that scares me the most from this film is the freakish “spider-walk” sequence, where Regan crawls down the stairs upside down and arched. The special effect here holds up today in tremendous fashion (as do most of the effects in this film, mind you). Depending on which version of The Exorcist you have seen, you have two “spider-walk” scenes; one with Regan’s tongue sticking out, and — the stronger of the two — one where Regan cries out for help and blood spills out of her mouth. To me, the latter is far more effective; this is a girl who is not fully possessed yet and is still cognizant as to what is going on, but she is also too far gone to be helped via traditional means (this is the version found in the director’s cut, along the spinal tap sequence as well).

-

The twenty-first century was blessed (or cursed) with its scariest moment right at the beginning, and it is discretely placed in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. There are two major factors that make the Winkie’s scene petrifying. First, it’s Lynch’s boldness to have a scene that is seemingly unrelated to everything we have seen thus far just pop up out of nowhere; you lean in to see what the deal here is. We see two strangers: one is discussing a nightmare that they have had while they have lunch (the poor soul recounting his dream has hardly touched his plate); his plus-one encourages him to keep discussing his dream.

This leads us to the second reason why this scene worlds: Lynch is spoon-feeding us what the jump scare will be, note for note. The dreamer is encouraged to face his suspicious — of a horrible man hiding behind the Winkie’s diner — to see that it is all untrue, and the film follows up; Lynch utilizes chilling sound design and reverb to make us feel uneasy about this. At the drop of a hat, the man’s reservations come true, and we get the fright of our lives as the mysterious figure pops out (just as we were warned). Mulholland Drive defies the false sense of security that films imply; knowing what will happen doesn’t prevent something from being scary if it’s done perfectly. This means — unfortunately, for the easily timid — that the Winkie’s scene will also be terrifying every single time you watch Mulholland Drive (if spoiling the scare didn’t cut it down, what will?).

-

Begotten is an underrated film when it comes to the discussion of truly horrifying motion pictures. Part of its experience is how director E. Elias Merhige over-processed the hell out of every frame to the point that it no longer even looks like a silent film from the twenties but, rather, an unearthed artifact left by a demon that we are not meant to watch. To prove this point, the film begins with a lengthy, hard-to-decipher image of what is essentially God comitting suicide via disembowling and slicing Himself. There’s very little in way of sound and discernable clues as to where this is, why this is happening, and other identifiable factors, but it is the mystery that makes this shot scarier to me; when your brain is doing all of the heavy lifting, I believe such a blasphemous image digs into your soul (even if you are irreligious, this devastating, disturbing look at self-sacrifice is not easy to stomach). The rest of Begotten isn’t any more clear, but it is this diabolical opening that sets the tone and ruins your day (or, if you’re me, your mind for the rest of your life).

-

Ah, yes. The Shining. One could pick a thousand things from Stanley Kubrick’s classic film (which may be the scariest film ever made), but — oddly enough — this selection was a no-brainer for me. What is worse than the axe-to-the-door, the bloody corridors and elevators, the thousands of pages with the same typed line, or — gasp — an apparition of a furry that pops up for no reason? It has to be the ghostly Grady twins who appear after a long shot (and one of a couple) of little Danny Torrence on his plastic tricycle; their appearance is graced with an unnerving gong crash. The camera keeps cutting closer and closer to these two sisters, who invite Danny to play with them via a monotonous, droning chant. As we get closer to them, we see snapshots of how they died: the crime scene is a haunting sight that will keep anyone up at night. The film cuts to Danny’s stunned reaction and his inevitable recoil; we are Danny in this moment, too. When Danny begins talking to himself after this spectacle to try and assure him that what he saw was not real, this only convinces the audience furthermore that it likely was; even the “resolution” here is creepy.

-

By my own rules, I cannot just select an entire film as a scary moment? Well, in that case, I will state the obvious: Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom is every bit as disturbing as its reputation insists. If you can stomach making it to the end of the film — so that’s past the sexual violence with teenagers, the eating of feces, the torture and so many other awful sights, you are given the final boss. The film is divided into four parts, and the final one — the Circle of Blood — is as abysmal as its name suggests (or even more fucked up, truly). After months of abuse, the remaining teens are given an atrocious sendoff as one last source of amusement for the Fascist leaders who have been using them as pets, sex slaves, and other humiliating devices. This climax includes branding, tongues being cut, eyes being plucked out, full-on acts of rape, and much, much more (believe it or not); meanwhile, the libertines — as expected — marvel at this sight from afar as if they are watching horse racing (meanwhile, the hired pianist cannot stand to live after seeing this massacre and commits suicide). This is an onslaught of almost every awful act of humanity being committed at once in a paradoxical cacophonous harmony; there is no recovery from this scene once you have witnessed it (perhaps this was Pasolini’s intention).

-

If Salò’s climax feels like an amalgamation of every human atrocity known to civilization, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’s payoff moment is a similar concept from the depths of our nightmares: acts so inhuman that we cannot even fathom what we are seeing. What makes this New Hollywood horror film special is that a vast majority of the film feels upsetting and tense, especially since the bulk of our characters are slaughtered in seconds and — a new concept at the time — Sally being the “final girl” once felt like she was going to die at any given moment; her survival feels miraculous (and has been copied relentlessly ever since to the point of parody and vapidness). When she winds up at the dinner table with the worst guests imaginable (southern cannibals who use the flesh and organs of their victims as food, materials for their furniture, ornaments, and many other “resources”), we are in a place we never thought was possible.

From the nearly-dead elder sucking on Sally’s blood-soaked finger to a look at what is on the menu (and who is expected for dinner, if you catch my drift), this pivotal moment from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre never lets up. It is a barrage of horror (the glorious close-up of Sally’s veiny eyeball is also a defining moment: the fright is far more than our sight can comprehend). I feel like I have a few heavy hitters on this list, but there’s something about this scene from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre that elevates it as the scariest scene in film history for me; perhaps it is how it reads as a symphony of the macabre, and how it flowing together almost feels right to me (and that connection with the worst of humanity makes me a little scared of myself, too).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.