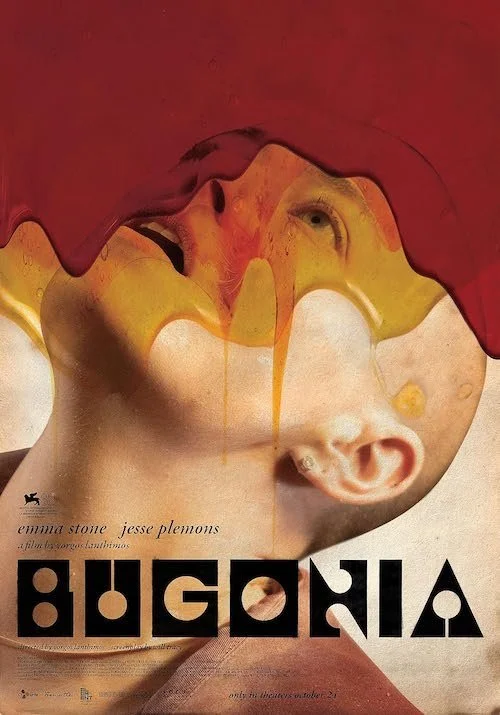

Bugonia

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: This review contains blatant spoilers for Bugonia. Reader discretion is advised.

I am a Greek weirdo, just like Yorgos Lanthimos: a filmmaker who is shaping himself as one of the greatest directors of contemporary cinema. I do not assume that everyone will see eye-to-eye with Lanthimos and his absurdist style, particularly because he frequently forces his audiences to partake in difficult experiments. The Killing of a Sacred Deer has you considering the fate of your own family members in hypothetical nightmares. The Favourite challenges what a costume drama can be, encouraging fans of the genre to watch something far more unorthodox and candid. Poor Things is a statement on societal misogyny, allowing us to root for a woman who starts off with the intellect of a child and slowly gestates into a brilliant mind and a force to be reckoned with. Then there is Kinds of Kindness: a film that led to one of my most read reviews. An anthology picture that was frequently pegged as confusing and difficult for the sake of it, I instantly connected with the religious allegories at the centre of its three tales. However, Lanthimos has become prolific with three films in just as many years. Can we admit that arthouse, satirical cinema is fashionable yet? No?

It is also unfair to declare that Lanthimos is becoming familiar at this point, and Bugonia is his statement as such (this is an adaptation of the Korean genre-bender, Save the Green Planet!) If anything, it appears as though this is the one time where you understand a Lanthimos film from the jump, and yet you also couldn’t be more wrong. Here is what is blatant. Teddy (Jesse Plemons) is plagued by conspiracy theories. With his mother (Alicia Silverstone) incapacitated after a drug trial went wrong (sponsored by pharmaceutical giant Auxolith: the very company he works for), Teddy is so mentally gone that simply being a flat-Earther would seem reasonable by comparison. He has his cousin, Don (Aidan Delbis) under his wing; Don is on the spectrum and trusts Teddy despite not fully comprehending what he is told. Teddy recruits Don to undertake a major mission: intercept an alien living amongst humans who has been sent by a society from the Andromeda Galaxy. Clearly a decision made through trauma, Teddy believes that the Auxolith CEO, Michelle (Emma Stone), is such an alien. They — and Bugonia as a film — waste no time getting to the point where Michelle is kidnapped and locked in Teddy’s basement.

Bugonia is sure to bother many viewers because of how effortlessly it manipulates them.

The premise is clear: Teddy and Don are destroyed by conspiracy theories and have attacked a high-level CEO. They shave her head because they believe that hair can connect to her fellow Andromedans. They believe that the bees are dying off (Teddy is also an apiarist) because the Andromedans are poisoning the insects, thus leading to the eventual demise of humanity. There is a lot more going on, but you get the point: Teddy and Don are clearly nuts. Oddly enough, Michelle deals with her predicament quite well. She talks with Teddy and Don with assuredness: as if there can be a way to fix this situation. Of course, the film only gets crazier and crazier, and yet Michelle still tries to remain calm and collected about everything; even when she is given shock treatment, is abused, or has a shotgun pointed right at her head. There is a subplot featuring a police officer, Casey (Stavros Halkias), who continuously checks in with Teddy and his wellbeing; it is revealed that Casey used to babysit Teddy years ago and molested him — he is trying to rectify this vile act (clearly something that permanently affected Teddy as well). Of course, Casey does a wellness check a couple of times while Teddy has Michelle trapped in his house; this builds suspense throughout the film.

For a majority of Bugonia, I felt like I was watching Lanthimos’ take on Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master; both films are character studies between two intellectually polar-opposite individuals. In The Master, it’s a battle between a manipulative cult leader and a shellshocked veteran who is beyond saving. In Bugonia, it is clear that we have two men who have been heavily corrupted by online doomscrolling and rabbit-hole echo chambers. However, there is also Michelle: a powerful CEO who is so driven by buzz words, marketing strategies, legal loopholes, and many other strategies; sure, this makes her look like a clever leader, but consider the lack of humanity she has especially when it comes to her lack of ownership or acceptance (like many moguls). This reads as a different kind of delusion to me: one that is more acceptable by society but is just as harmful to the wellbeing of all. Consider how many people eat up all of the fabricated rhetoric of, say, Elon Musk. Michelle being richer, better-presented, and stronger with her way of words does not make her any less of a problematic figurehead than Don (I won’t include her with Teddy, who has clearly crossed many lines to the point of becoming a full-on criminal and psychopath); the main difference is that it is easy to see how a conspiracy theorist is an unhelpful idiot, but many people fall for the rich elite’s deceptions time and time again. The promised future explained by CEOs, too, is false.

Bugonia lays its points quite clearly for its audience, but the biggest trick that the film pulls off is allowing viewers to get invested in the wrong things. It is so easy to judge Teddy, especially when you see how far he has gone (to the point that he has, as is revealed, murdered multiple people and kept their body parts in his basement to conduct more research). However, we eventually arrive at the sequence that has everyone talking (and, thus, I must give my two cents as well, seeing as in this instance it is next to impossible to cover this film without spoiling its biggest play). At the end of the film, Teddy has convinced Michelle to take him to her home galaxy; she is apparently using a basic calculator to call her mothership to retrieve her, and will get transmitted onto said vessel by hiding in her closet. This sounds like a load of nonsense and a means of tricking Teddy. Teddy doesn’t want to take chances and has strapped a bomb vest onto himself; Michelle is clearly perturbed by this. Teddy wants to be transmitted first and goes into the closet; Michelle backs away, and the bomb goes off due to the rise in temperature (Teddy’s body heat, and the stuffiness of the closet, presumably). Teddy is long dead.

While receiving medical attention, Michelle begins to act suspiciously; this is when Bugonia begins to prepare its hand to slap the face of every viewer. Michelle heads back to her office, grabs that same calculator and heads into that same closet; there is no way that Teddy was right. Suddenly, we are indeed in the Andromeda Galaxy. Michelle, an alien queen, addresses her committee and deems the human race is beyond repair. The Andromedans kill off every human; the bees begin to flourish again as a result (okay, so maybe Teddy wasn’t right about everything). The credits begin to roll. This twist ending has been instantly controversial, especially since many viewers consider it a game changer that, to some, ruins the entire story. What do you mean that Teddy was right? I view this ending as one of two possibilities. The first: This ending is what Teddy hopes for when he dies and his decapitated head flies across the room. As much as that would be nice for many to believe, this is likely not the case. The second possibility: This is all true, and alien Michelle has no faith in how humans treat each other (whether it’s Teddy murdering and torturing people, Dom being driven to suicide, or Casey abusing a child). Of course, Michelle doesn’t know about all of these awful actions, but she — the head of a pharmaceutical juggernaut — has clearly seen enough. The human experience is a failed one. Some viewers may feel cheated by this ending, and I cannot fault them for that. Some may feel that the lens has been turned on them. It’s our own damn fault.

Bugonia takes a bold risk by making its audience feel delusional.

How could the film lie to us? How could Lanthimos deceive us? Anyone who watches Bugonia and believes that Lanthimos is a flat-Earth believer and a lunatic clearly didn’t understand the assignment. I believe this is Lanthimos’ way of getting us to connect with those who are mentally far gone in the world. In the day and age of social media, influencer culture, and algorithms, the internet — what was once a well of all things informative — has become a cesspool. In fact, the dead internet theory — one that states that social media will be driven by bots creating and responding to content, without any human input in sight — is already coming true. Of course vulnerable people will be misled. I believe that the isolation during the pandemic has done a number on many people; our mental health has taken a severe hit. With an ending like this, we understand Teddy just a little bit more and what is true to him (his reasons for being desperate become clear); I’d argue that Bugonia is empathetic to Teddy the whole time, understanding how sad it is to be this lost, having strayed so far away from reason.

With this angle, Bugonia is showing how easy it is to be misled. Forget what Teddy states and does; you are this convinced by a film. You pick your side almost instantly. You are unwilling to listen to a character as soon as the film starts and, I suppose, it seems like it is for good reason, but that is beside the point. Art is meant to be a conversation, and we have been conditioned to be firm and not listen at all costs; this leads to poor media literacy and awful misreads. You watch a film like Bugonia and expect to side with Emma Stone’s character before you even begin; what is the point of art if you refuse to have this conversation between the medium and yourself? Even if it renders the film far more absurd and nonsensical than you could have ever imagined, Lanthimos pulls the rug from underneath you to reinstate this notion: art is meant to push you and leave you thinking about what you just saw. What satisfaction would come from a film that you blindly nod your head to and agree with everything you see? I don’t expect motion pictures to be provocative, taboo, or contrarian, but I do think that we are losing a sense of what art can do for us in the day and age of content creation consumerism; you learn nothing from swiping every twenty seconds onto the next thing, and yet we are convinced that this is a reliable form of research now. Even though we may not agree with what he says, and despite Bugonia going against expectation, we essentially are no better than Teddy, as we aimlessly accept every little tidbit of information as truth.

On top of this bold strategy is a battle between two powerhouse performances: Plemons’ certain-uncertainty (and all of the anxiety that fuels him), and Stone’s subdued assertiveness. This is a fight of wits between a pair of beings who are extremely set in their ways; even when you feel like Teddy is floundering, there’s something about his drive that makes him compelling to watch, as if he is a rabbit trying to gnaw his way out of a trap. Between the amber cinematography (courtesy of Robbie Ryan) and the ambitiously nervous score (composer Jerskin Fendrix works with Lanthimos yet again), Bugonia feels like a lost artifact of pure paranoia; as if we have stumbled upon a frantic diary entry about how the world didn’t listen. At the end of the day, Bugonia is a major gamble that I accept. I know that this film will piss off many viewers, but this kind of challenge is what films need when we have become so accustomed to franchises, remakes, sequels, and all other kinds of promised formulas; why did we as a civilization accept to be so dulled down and susceptible to manipulation?

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.