Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Steve McQueen Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers who have made our Wall of Directors (and other greats)

Steve McQueen (no, not that one) is one of the most exciting contemporary directors thanks to his upfront depictions of social realism and devastation throughout history. To me, he is a consistent filmmaker who might slightly shift his style and intensity with each and every project but remains someone with something to say (and an informative angle with every story). McQueen has risen as one of the biggest names in modern day cinema, only to seemingly fade a little bit again in popularity; I believe this is because he has never wavered or bent under pressure (or has played the Hollywood game to make what is expected of him). It is a bit sad but also refreshing to see a director like McQueen always remain true to himself an the kinds of motion pictures he wishes to display. His very worst works are still quite good because he made them on his own terms with as little meddling as possible. Then you reach the bulk of his career: great-to-stunning films. I hope a list like this one can plant McQueen back into the conversation of many cinephiles. I will not be including his many short films or series here, but I will be adding each film that is a part of the Small Axe anthology (since the miniseries is essentially a collection of five feature films). Here's a miniature tribute to one of the best and most important directors working today. Here are the works of Steve McQueen ranked from worst to best.

11. Alex Wheatle

The fourth part of McQueen's Small Axe anthology series, Alex Wheatle is a biopic (of sorts) of the novelist of the same name who partook in the 1981 Brixton uprising; McQueen's hour-long film depicts Wheatle's life as one where he felt ostracized for being Black in a predominantly white neighbourhood before moving to Brixton and feeling at home. Despite the potential depth that could have arisen from a film about a sharp mind and a strong writer, Alex Wheatle is easily McQueen's weakest film: while not a bad one, it feels his most safe, traditional, and as though it exists just because (without saying anything revelatory or new); this is a crying shame given how strong of a voice McQueen typically is. I suppose Alex Wheatle works as part of Small Axe's episodic look at the communities of Black immigrants in London (hence why it exists); I just wish the film said more about Wheatle and the importance of communities; if McQueen was opting for a minimalist and more quiet approach, it doesn't come across through this film which amounts to "pretty good but forgettable."

10. Blitz

Despite being a director known for having some of the more harrowing motion pictures in recent memory, Blitz sees McQueen operating at a Spielbergian level of sentimentality and hope. A capturing of what London underwent when it was blitz bombing by Germany during the Second World War, McQueen paints a portrait of separated family members trying to reunite amidst these harsh and unforgiving conditions. I may have liked Blitz more than the average cinephile (I found much worth in its world building, performances, and scope), I still find this one a little bit too toned down to the point that it dullens McQueen's typical sharpness. Still, seeing a great director operating at any capacity is always a treat, and McQueen's intended warmth and passion here still shine through a film that can feel like it is holding itself back.

9. Occupied City

McQueen's sole documentary is Occupied City: a towering, four-and-a-half hour behemoth that depicts the Nazi occupation of Amsterdam during the Second World War; I feel like McQueen intended on this documentary and theBlitz being sister films of sorts, given the fact that both films — released one year apart — both went into various forms of war based takeover (the slow, methodical method of occupying a city, versus the speedy, ruthless way via destroying an area within seconds). I don't have such an issue with the length of this film as much as I do the fact that it feels tonally all over the place and like a bit of a chore at times; even so, McQueen being this thorough is enough of a privilege if you are patient enough (when you are occasionally lulled into a spell, you may find yourself as grateful as I was that Occupied City is this dedicated and philosophical with its findings). Now, the supposed thirty-six-hour version of the film might be a tall order.

8. Red, White, and Blue

Midway through McQueen's Small Axe series is this true story rendition of officer Leroy Logan (played expertly well by John Boyega): a Black member of the London Metropolitan Police force who wishes to abolish police brutality against Black Londoners from within the organization. This tall order arrives in the form of Red, White and Blue (which are clearly the colours of the Union Jack, but I cannot help but wonder if McQueen was also referring to the prevalent cases of police-based conflict in the United States around the time of this film's release). Logan finds himself dismissed by the other people on the police force while also disassociated with the members of his community and family; he is isolated trying to fight a seemingly impossible battle alone. This feels like McQueen handling a straight forward political drama with enough intuition and drive to make a film like Red, White and Blue compelling.

7. Education

The final part of McQueen's Small Axe anthology series is Education: it is the one part of these five parts that has only significantly grown more with me the more I think about it (I liked it quite a lot when I first saw it, but now I think it is excellent). We follow young Kingsley who is on the verge of entering his teenage years when he is deemed "slow" by his school and is held back; what is actually transpiring is a crippling form of segregation that was used to prevent Black children from ever having an opportunity to succeed whatsoever (it's frankly disgusting). This is a time where McQueen trying to make sentimental cinema works incredibly well, seeing as we are meant to be experiencing these realizations through the eyes of an aspiring, intelligent child; the weight of the racism against the warm-enough tones of Education hurt even more; it makes Kingsley's perseverance feel triumphant, at least. It is a film that made me mad when I first saw it; the more I am aware of these kinds of practices still being used worldwide, the more enraged I am (yet grateful for Education for warning the masses).

6. Mangrove

The first part of McQueen's Small Axe anthology is by far the longest of the five. If the other parts were meant to be snippet depictions of what immigrant Londoners have experienced, then Mangrove was a two-hour statement that ushered you into McQueen's headspace. Based on the Mangrove Nine (and their rioting as an effort to protect The Mangrove restaurant, which was frequently targeted by police brutality), Mangrove is a slow-burning back-and-forth battle that never eases up; if much of Small Axe feels like McQueen's efforts to try and soften himself after being the bastion of pummeling cinema, Mangrove is essentially the angriest he got through this series). What kicks off as an intense drama becomes an engrossing legal thriller once Mangrove reveals all of its cards. Any fans of McQueen's traditional style owe it to themselves to see Mangrove.

5. Hunger

McQueen's feature film debut is exactly the kind of punishing film that we have come to expect from the visceral auteur. An excruciating drama about the Irish hunger strike in response to the Troubles (starting in 1981) taking place in a Northern Ireland prison, McQueen's indie film is a testament to what conviction and perseverance look like when people are this in tune with their causes; McQueen's film is devoted enough to show the full extent of resilience. Featuring a breakthrough performance by now-mainstay Michael Fassbender (who has worked with McQueen a few times since), Hunger was evidence that McQueen had political points to make from right out the gate: that he was going to use cinema as a means of combing through history and pointing out these essential talking points for us to reflect on with modern eyes. Here, McQueen depicts a divided nation, a corrupt prison system, and the quest for fulfillment and solace.

4. Widows

When I think of stupidly underrated films in contemporary cinema, one title that I can never shake off (especially since it remains under-discussed) is McQueen's exhilarating political thriller, Widows. Teaming up with the great Gillian Flynn to adapt the British series of the same name (and, goodness, what an adaptation), McQueen takes to the systemically imbalanced city of Chicago to find four disgruntled widows — tied to the criminal underground by their late husbands — who aim to settle the score for good. What remains is the understanding that one's misdeeds will leave others to answer for them (yes, even the innocent), as well as a vision of an America that is hellbent on playing the odds for a very small selection of powerful people (while everyone else is left to fester). If Widows is McQueen's answer to action cinema, he never loses sight of his powerful direction nor his ability to leave audiences feel like they are careening over the edge of a cliff for entire runtimes.

3. Shame

Hunger was McQueen's breakthrough film, but Shame was the motion picture that introduced the British artist to American audiences in full force. In it, we follow a plagued protagonist who is steered by his awful addictions to pornography and sex (to the point that it is affecting his work and personal life). Character Brandon's obsessions stain him toxic and bitter (and everyone else around him ephemeral); he strives for love and affection but has lost all sight as to what these even mean while in pursuit of that ultimate erotic high. Brandon is played by Michael Fassbender with one of the greatest performances of this century (how he was not an Oscar winner, let alone nominee, is an atrocious sign of negligence by the Academy); he possesses Brando levels of self-disdain within manipulative power and corrosion. McQueen's film never flinches with its upfront vulnerability to the point of extreme discomfort. With Shame, McQueen wasn't just this British director trying to tell American stories: it was proof that he understood many people worldwide better than they knew themselves and their vices.

2. Lovers Rock

The best part of McQueen's Small Axe anthology set is the most antithetical film he ever made. Sure, he has tried to make touching films since Lovers Rock, but they are still trying to tell stories of distress and misfortune. Never before or since has McQueen made a film that was strictly about letting go of the atrocities that surround us; usually, the director allowed darkness to envelop us. Lovers Rock stations us in the middle of a two-story house party with many different characters and their assortment of stories coalescing. Of course there will be tribulations in this film, seeing as it has a fully-realized narrative and a congruent depiction of Black immigrants rejoicing and connecting over their mutual love of freeing music. As if McQueen was channeling the nostalgic, sublime whimsy of Wong Kar-wai, Lovers Rock is a heavy indication that there is strength in numbers, peace in culture, catharsis in the arts, and beauty all around.

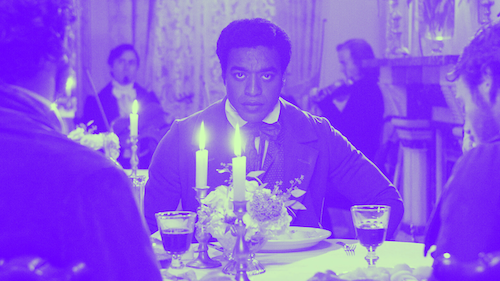

1. 12 Years a Slave

One of the greatest Best Picture wins of my lifetime was when 12 Years a Slave took home the top prize at the Academy Awards. For starters, it was a major breakthrough as the first film by a Black director to win. Secondly, it outright deserved its win as one of the best films of its decade (and my choice of the strongest film of 2013). What began as an invigorating moment has sadly become a bit of a peculiar case: why aren't people talking about 12 Years a Slave as much as they once were? A benchmark moment in the historical drama genre, 12 Years a Slave places us with Solomon Northup who was forced to be a slave despite his declared freedom; he was isolated from his family and tortured for the duration that the film's title decrees. In McQueen's version, Northup begins level-headed and with a desire to make it out of this crisis alive, declaring "I don't want to survive. I want to live," essentially stating that he will easily go back to the way things were for him. It doesn't take long for him to surrender and cry out "I will survive! I will not fall into despair!" There is well over half the film left by the time Northup is this broken, and yet he perseveres.

To me, 12 Years a Slave is just as booming, heartbreaking, magnificent, brutal, and shocking as it was when I first saw it years ago. The artistry is still tremendous, meticulous, and mesmerizing. The narrative remains nauseating and depressing. I have not felt any less of what 12 Years a Slave intends for us to experience whenever I revisit this film. Why have I seen the asinine claims that this film is one that was created with Oscar bait in mind (when the film is nothing but explicit with its challenging nature)? Why has this film been not been steadily in the discussion of the strongest works of the twenty-first century when it could easily lead that charge? All I know is I do not care to be a part of this wave of dismissive snobbishness when a film as life-changing and ambitious as 12 Years a Slave exists (and when a visionary as strong as McQueen is around to make art as prescient, important, and effective as this). I will continue to sing its praises regardless of whether or not it is fashionable.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.