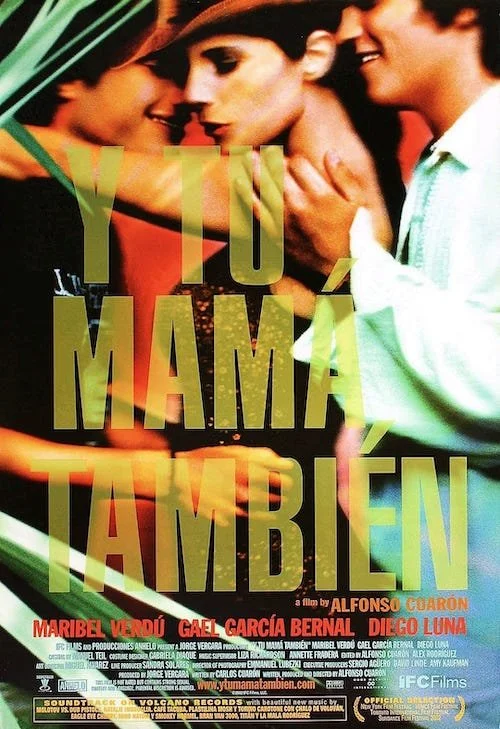

Y Tu Mamá También

Written by Octavio Carbajal González

There is a stage in life when movement feels like a form of knowledge. When leaving — a house, a city, a version of oneself — seems enough to generate meaning. Alfonso Cuarón’s Y Tu Mamá También (2001) understands this illusion intimately. Rather than celebrating it, the film observes how it slowly fractures, how motion promises clarity but delivers something more unstable: awareness.

Throughout his filmography, Cuarón has treated space as a primary force. His characters do not simply inhabit places; they are reshaped by them. From the protected fantasy of A Little Princess (1995), to the erotic disquiet of Great Expectations (1998), and later the historical pressure of Children of Men (2006) or the memory-saturated textures of Roma (2018), movement becomes a way of thinking. Y Tu Mamá También stands at the center of this trajectory: smaller in scale, looser in form, but sharper in its understanding of how bodies, class, and time collide.

The story begins in Mexico City at the end of the 1990s, a chaotic and vibrant place still enveloped in slowness. Before google maps and constant connectivity, direction depended on folded maps, handwritten notes, and the unreliable kindness of strangers. Time moved with more friction, plans were porous and getting lost was not an exception but part of the rhythm. Within this atmosphere move Tenoch Iturbide (Diego Luna) and Julio Zapata (Gael García Bernal), two seventeen-year-olds bound by repetition, and an intimacy they do not know how to name. Their friendship is loud and competitive, which echoes a classic ritual of masculinity. Class difference already separates them, though neither wants to acknowledge it. Tenoch belongs to political privilege; Julio inhabits a more aspirational middle ground.

When their girlfriends leave for Europe, time suddenly loosens its grip. Days lose their internal structure, and boredom begins to arise. Into this open interval enters Luisa Cortés (Maribel Verdú), a woman shaped by a different kind of displacement. She is Spanish, recently arrived in Mexico through marriage, and carries the quiet tension of someone who belongs nowhere entirely. Luisa is not looking for adventure in the youthful sense. What she seeks is a pause in her life. When, during an uneasy dinner, the boys invent a destination called “Boca del Cielo”, and the lie resonates with her in an unexpected way. In a pre-digital world, where places could exist simply through description, invention still had weight. A beach could be real if someone agreed to drive toward it. Luisa accepts not because she believes in the place, but because movement itself offers temporary relief from her loneliness.

The road operates as narrative momentum; stillness delivers meaning.

Once on the road, Mexico unfolds not as postcard but as accumulation. Leaving Mexico City, they cross the State of Mexico and Puebla — toll booths, industrial outskirts, towns that flicker in and out of view. Vendors, checkpoints, roadside meals, overheard conversations interrupt the journey. The narrator (Daniel Giménez Cacho) quietly punctures the boys’ self-absorption with factual asides about the lives surrounding them, reminding us that every trip passes through other histories. As they move south toward Oaxaca, the country begins to slow them down. Heat thickens the air and speech softens. Poverty becomes less abstract and more intimate, visible in gestures and endurance rather than spectacle. Mexico ceases to function as background and becomes a presence.

Gradually, Luisa becomes the film’s gravitational center. Verdú plays her with clarity and restraint: warm without sentimentality, ironic without cruelty. She listens more than she explains. As the journey nears the Oaxacan coast, the narrative loosens. Nights stretch, alcohol replaces direction, and sex becomes a central part of the journey. The invented destination finally appears not as revelation but as something provisional. What once looked like idyllic begins to fracture, envy and rivalry overlap without resolving. When the journey reaches the end, time resumes its authority. The road collapses into memory and the beach becomes anecdote. Life continues, indifferent. What once felt expansive becomes difficult to name.

Emmanuel Lubezki’s camera observes rather than instructs, attentive to dust, skin, pauses, and duration. The film’s soundtrack blends rock, folk, classical, and traditional Latin American music in a loose, almost accidental way that mirrors the film’s emotional drift. The performances by Diego Luna, Gael García Bernal, and Maribel Verdú feel less acted than lived. Meaning gathers quietly, through proximity rather than declaration.

Silence carries more weight than the journey ever did.

In this sense, Y Tu Mamá También shares an affinity with W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, a book structured around walking not as destination but as delay — a way of thinking through movement, of letting memory and awareness surface obliquely. Like Sebald’s narrator, these characters travel not to arrive but to suspend time, to postpone what they already sense is inevitable. And ultimately, the film is not about sex, nor even about youth, but about the moment when experience begins to carry consequence. It echoes Octavio Paz’s idea, in his acclaimed book-length essay The Labyrinth of Solitude, that identity in Mexico emerges through contradiction, through what is felt but rarely spoken. Some journeys exist only to teach us what we will later lose — and that understanding often arrives too late to change anything, yet early enough to leave an eternal mark in our lives.

Octavio is a passionate cinema enthusiast from Mexico City, he mostly enjoys watching arthouse films from all over the globe. His reviews are published on "Vinyl Writers" (www.vinylwriters.com).