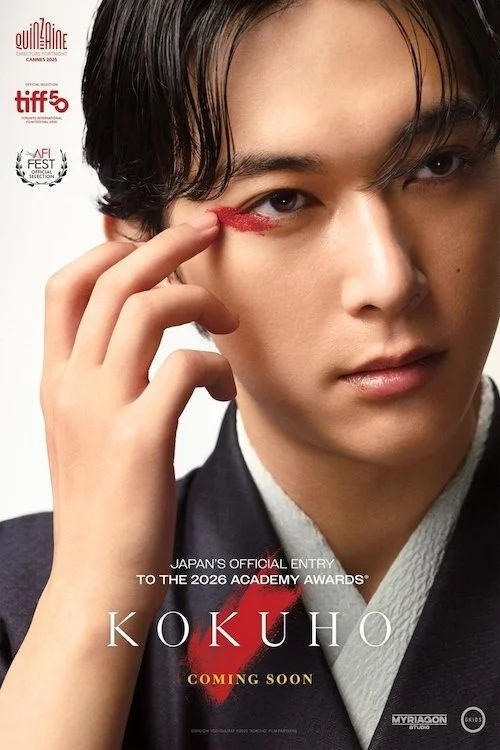

Kokuho

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

One of the bigger surprise at 2025’s Toronto International Film Festival was a curious film about kabuki theatre that was brought to my attention periodically. I was told I would like it, and I promised to keep my eye out for it (I missed the boat at TIFF but thought the film sounded interesting nonetheless). Little did I know that this film would be Kokuho by Lee Sang-il, that it would be the most profitable live-action film in the history of Japanese cinema, and that it would be an undeniable awards season contender for its makeup and hairstyling (it did wind up making the final group of nominees at the 98th Academy Awards). This film wound up being an absolute sensation in 2025 (and, to be fair, already in 2026 after new audiences are now aware of its existence). Oh, to be one of the first viewers of this film well before the world got swept up in its power; I sadly know not what that feels like, but I know people who do. However, I consider this pleasure to be better late than never, and the hype is real: Kokuho deserves its nomination for its exemplary makeup and hairstyling brilliance, and the film is truly quite something (if the Best International Feature Film category wasn’t so competitive and stacked, I could see Kokuho being a part of that conversation as well; consider it one of the honourable mentions there, then).

The film reminds me a lot of Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine and how the Chinese classic compared the Peking opera to tumultuous lives and unrequited queer romance. With Kokuho, the pain within the tragic stories of kabuki theatre is used to resemble the tribulations within life; much like Farewell My Concubine, we follow our characters throughout the majority of their lives. The protagonist here is kabuki actor Kikuo Tachibana (Ryo Yoshizawa and Sōya Kurokawa), who is picked up by esteemed actor Hanai Hanjiro II (Ken Watanabe) after Kikuo’s father is killed by members of a yakuza group (Kikuo’s father was a member of the rival Tachibana group). Under Hanai’s purview, Kikuo’s relationship with theatre is furthered, and we see many of the people he connects with along the way (including Hanai’s son, Shunsuke, played by Ryusei Yokohama and Keitatsu Koshiyama). The film spans decades of Kikuo’s life, from when he is a child in 1964 all the way to 2014. Kokuho boasts many intricate plot details throughout this story that are more than just “Kikuo’s life as an actor”, and the many people who come and go through his story turn this play into a grander vision of a labyrinthine life.

Kokuho is one of the biggest surprises of 2025 cinema. It is a Japanese epic that blends the complexities of life with the majesty of art.

Many different styles of performances are shown throughout Kokuho, and Lee saw fit to add intertitles detailing what each of them are and their significance. Some may see this as hand-holding art; I see this as didactic filmmaking that rejects the act of gatekeeping. Now, we are able to not only learn more about kabuki culture, we are able to understand the purpose of each moment even more, as if we are wandering around an art gallery or event and are able to assess the art with our own gaze while also paying attention to the exhibitionist’s inference. What could have been an over-explanation instead renders Kokuho a living portfolio of a life, and I think it is quite the clever gamble that could have sullied an extravagant film (it instead strengthens it).

This is a glorious and gorgeous film about an artist and their art that continued to astound me more and more the further it continued. I was so engrossed in Kikuo’s life, the hardships he endured, the flaws that defined him, and the exaltation he craved. I tried to take note of the makeup and hairdressing considering the film’s nomination, and the accolade was beyond warranted; what kicks off as an exposé of what theatre makeup and wig designs looked like back in the day turned into the evolution of such creativity while also cleverly — and realistically — aging and de-aging our stars throughout the course of the film; this is a complete masterclass of the craft, and I do hope that this nomination brings more people to such an indescribable feature film like it brought me. The film’s production in general is exquisite, with each and every moment in time captured by realistic, pretty sets, costumes, nature and architecture. Seeing as Kokuho is presented like a multi-part play, all of the central performances are as strong as they need to be. This isn’t just a kabuki play done in the form of a film: this is the act of witnessing the transformation of art throughout time via a cinematic vessel. Kokuho is the kind of epic that marries the challenges of art cinema with the spectacle of mainstream flicks to create a unified pilgrimage through time and culture for all to enjoy, and I think all of its adoration (and its reputation which only continues to grow) are beyond earned.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.