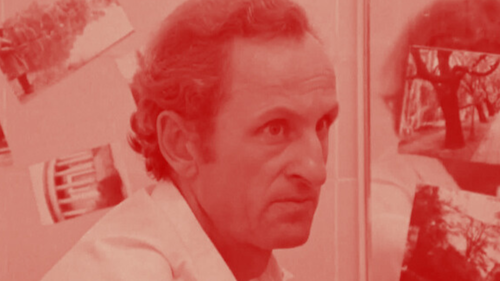

Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Krzysztof Kieślowski Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Directors

Not many directors are capable of taking arthouse works and making them applicable to the masses without losing any of the intended vision. Krzsztof Kieślowski was one of the greats with accomplishing the above, and he sadly died at the age of fifty-four when the world was finally getting to know his works through and through. To be fair, the Polish giant retired young, perhaps feeling as though he accomplished what he set out to achieve (then again, he was preparing to work on another trilogy; these screenplays were tackled by different directors and resulted in Tom Tykwer's Heaven, Danis Tanovic's L'Enfer, and Stanislaw Mucha's Nadzieja). He was taken from us too soon, but his works will forever remain as artifacts of European artistry and as influences on cinema on a global scale.

To avoid mandatory military service at a young age, Kieślowski studied art (while also starving himself so he couldn't meet any health requirements to serve). This would lead to Kieślowski vying to make documentary films, focusing on the middle class's daily routines and methods of survival. Kieślowski would always be fascinated with what made everyday people tick. However, his affinity for documentary filmmaking would eventually cease after nearly twenty such examples. During the production of Workers '71, he was continuously having to bend to the Polish government's censorship restrictions. His other film, Station, was almost subject to serving as a piece of evidence in a criminal case. He deemed that documentaries could no longer properly portray honesty effectively, and that art could have more truth within it (albeit in the eye of the artist); he would exclusively make narrative works from this point onward.

With that in mind, Kieślowski still wanted to analyze how people operated, and his films are almost exclusively character studies of behaviour, spirituality, perseverance, and sin. Despite identifying as an agnostic, Kieślowski would frequently reference Christian themes perhaps as a better way to try and deduce what people are like. This is evident in his colossal effort, Dekalog, which is around ten hours long and split up into ten episodes with each part meant to represent a contemporaneous depiction of the ten commandments of Christianity. Here, Kieślowski is able to connect with all walks of life without ever imposing his specific views on others. Throughout his prime, which oddly came at the end of his career (usually, this would be the point when artists lose sight of what they want to pull off), Kieślowski broke the mold as to what a feature film could look like, how it can be watched, and the intersectionality between different projects, between viewers and films, and between himself and where he called home (be it Poland or France, the latter being more of a career-based commitment, but nonetheless).

The majority of Kieślowski's strengths lie in his feature films, so I will focus on those today (he has many shorts and documentaries that would extend this list by quite a lot as well). However, in being picky I will also be lenient. I will include the television-based films, including Dekalog; this might feel like an anomaly, but I do see this as a ten-hour, anthological film more than a television series (miniseries were initially meant to be methods of conveying longform films that could not be shown in theatres). However, since I am including Dekalog as its own entry, I will not be including the two films that stemmed from it: A Short Film About Killing, and A Short Film About Love. It would feel redundant to go over these works and Dekalog, and the paradox of having these separate films rank lower than a few other titles while also placing where Dekalog is placed just doesn't sit well with me (I do think highly of them as separate films, mind you). I consider all of these feature films worth watching, but the top five are Kieślowski at his undeniable best (they are also clearly his most popular titles as well). I will also preface this list by declaring the highest ranked film one of my all time favourites and an unparalleled masterwork of cinema. Here are the films of Krzsztof Kieślowski ranked from worst to best.

13. Short Working Day

Kieślowski's weakest feature film is still fairly impactful. Clearly frustrated by how frequently his documentaries were hindered by governmental interference, Kieślowski's Short Working Day -- a depiction of the 1976 protests in Poland — is a fairly scathing look at authority figures who fail their people (shown in the form of a stirring unrest throughout the film). Case in point: Short Working Day wasn't even shown for over ten years after it was filmed, so either Kieślowski was prevented from showing it, or he was displeased with the end result. Even so, this is quite a decent thriller that is sure to whet your appetite should you be craving a politically chaotic film of this nature.

12. The Card Index

Kieślowski's television film, The Card Index, involves a partisan looking back on his youth during wartime in Poland. Much of the film is meant to be the representation of a mind crushed by trauma and conflict, but I don't feel like Kieślowski had the expertise necessary to pull it off quite just yet (it wouldn't take long for the auteur to go above and beyond with his execution); I also think the use of television as the method of exhibiting The Card Index wasn't doing the film any favours (although that wouldn't hinder Dekalog). Still, if you want to see the early stages of a director who would be able to create modern forms of cinematic mythology, The Card Index may scratch that itch.

11. Personnel

Kieślowski's debut feature film, Personnel, is also a television film that feels quite primitive in nature; again, even seeing Kieślowski at his greenest is quite a treat. There's a dialogue between the politics of society and the entertainment industry in this film about a member of a theatre company and his unfavourable realizations. Stemming from the real frustrations Kieślowski was feeling early in his career, this 1975 film is an accurate enough depiction of the limitations found within art and civilization — usually at the hand of others, and out of your control. Kieślowski would be able to convey these ideas better later, but Personnel is a great first swing at such a film.

10. The Scar

The Scar surrounds a new chemical factory in the process of being built; meanwhile, the concept of a utopia that takes care of all of its citizen gets offered. However, in The Scar, the permanent damage of a negligent society and its short-term gains is irreparable. Kieślowski's first theatrical film is just as irked as his other early works: it is built upon the frustrations of a world that condemns most of its inhabitants (and the suffering people who refuse to fight for change). While I do quite like this film, I appreciate his ability to tell stories beyond mainly cynicism and retaliation later on in his career.

9. The Calm

By The Calm, Kieślowski was starting to figure out how he wanted to tell stories. He was still relaying his anguish with skewed class systems and intolerant governments by the time his film of intended retribution was released, but there is at least a smidgen of hope here (even though The Calm still surrenders to the evils of humanity). As we follow a man released from prison who wants to seek a better and changed life, we at least see an effort to be reborn; in a world so driven by malice and corruption, however, this change of heart doesn't last long (even if the intention does). Kieślowski at least implores us to persevere.

8. Camera Buff

Part of Camera Buff feels autobiographical; Kieślowski imposes himself in the film as a factory worker with a camera who becomes passionate about what he can capture. That is, until, his hobby becomes a means of propagandistic conveyance; why does this sound familiar? However, Kieślowski does more than just point fingers at others with Camera Buff. Here, with a protagonist who is becoming transfixed by this medium, Kieślowski sees himself in the shoes of an addict: a filmic fiend who is incapable of separating himself from his craft. Did Kieślowski think he was no better than the officials who tried to censor his work? Did Kieślowski think that film — in a way — censored reality because of forced perspectives and the bias of the capturer? Either way, I feel like Camera Buff was a major turning point for Kieślowski in terms of his artistic wisdom and his perception of self.

7. No End

Part ghost story and political drama, No End is a martial law story told in hindsight; it wouldn't be the last time that Kieślowski would break the walls of reality to, in return, depict it. Our laws and choices surpass us long after we are gone, and such is the case in this tale of a dead attorney and his wife's efforts to salvage his life, his work, and his ongoing trials. What transpires is highly bittersweet: the recognition of legacy (that of which surpasses us) and the facing of mortality. With a moving yet heavy conclusion, No End is an early test by Kieślowski to see how many emotions he could blend together at once (something he would perfect for a certain trilogy).

6. Blind Chance

We are almost at Kieślowski's biggest five works, but I must iterate that Blind Chance is almost as great as his most well known titles and should not be ignored. If anything, it is as capable — nay, gifted — at showing the power of morality and choices. Character Witek is given a brief scenario: he wants to catch a train. Blind Chance goes through three different realities where Witek's outcomes change depending on what he decides to do. Sneakily an anthological film (and a great one at that), Blind Chance is highly effective at making us second guess every move we make in real life; in that same notion, Kieślowski is utilizing the power of cinema — and the state of limbo characters find themselves in until the director gods command them to move — to prove this point. If you like the most popular Kieślowski films and haven't seen Blind Chance, you are doing yourself a disservice.

5. Three Colours: White

We have finally reached what I consider to be one of the greatest trilogies of all time: Kieślowski's Three Colours. Each film is meant to be antithetical to a common cinematic genre, all while representing the different identities of France and basking in the colours of the nation's flag. The weakest film of the three (but barely) is White: an anti-comedy that takes the usual antics of a screwball caper and places them on the head of a poorly tragic protagonist who keeps getting poor hands dealt to him. However, against the previous cynicism that once drove Kieślowski's films, White is instead grateful for life, forever presenting that white light not at the end of the tunnel but instead behind us. It does bother me when people greatly detach White from the other two films of the trilogy because I see a near-equal here; it might not be as devastating or emotional, but White is just as gorgeous and affirming.

4. Three Colours: Blue

The other two films in the Three Colours trilogy are a bit harder to rank for most, so it isn't lightly that I have Blue — the anti-tragedy — placed anywhere but first (however, I think I have my reasons). Blue is one of the great films to handle depression especially because Kieślowski never caves in to convention with how cinema expects sadness to be conveyed (yes, this film, which is one of the bluest looking of all time, is less melodramatic than many other tear-jerkers). As we spend time with Julie after a horrific accident claims the lives of the rest of her family, we get so much more than ache from the film and its magnificent lead (Juliette Binoche). In a way, Blue encourages us to both face the agony headfirst while also recognizing that depression is far more textured than constant crying: to be a broken person incapable of feeling anything at all is a far worse fate than being perpetually sad.

3. Three Colours: Red

Kieślowski's final film and the conclusion to the Three Colours trilogy is Red: the anti-romance. Love exists in many forms outside of purely romantic desires, and Kieślowski represents that in this glorious, unconventional look at the universal conquest to be adored. Once Kieślowski begins to question the ethics of peering on the lives of others and the concern with how people live their lives, he poses a fascinating point: in trying to find hope in other people, are we projecting our insecurities onto those who we are supposedly well-wishing? Will we ever find love when we become privy to how loveless the world can be? Red also does the heavy lifting of linking all three stories in an exhilarating way that will forever render me speechless when I arrive to this sequence: it unites all of the exuding emotions of humanity (love, sadness, joy) in a convergence that would make Robert Altman nonplussed.

2. Dekalog

One of the most ambitious film projects of all time, Kieślowski's Dekalog takes all ten of the commandments of the bible and turns them into a series of frigid, shocking fables, modernizing the black-and-white teachings of Christianity and applying an ambiguous grey to each and every lesson. Is morality truly this simplistic? What constitutes as right and wrong? All ten stories are tethered to the same housing project, as if these passersby are all silently suffering and unaware of what is happening next door. Kieślowski leaves it all on the line come Dekalog, daring to ask questions that so many other directors wouldn't ever dare to attempt. While a massive undertaking to watch (I have only ever seen it in full once, admittedly), Dekalog is a project that will rewire your brain (yes, even those who don't practice Christianity). Not only does it shatter the objectification of religious norms, it breaks what a film can be (the fact that you can technically watch any part of this film in any order is quite something); should it count, it might be the greatest anthology film of all time.

1. The Double Life of Véronique

It may be atypical to place anything but Dekalog or any of the Three Colours films in first place, but I need to emphasize that The Double Life of Véronique is one of the best films I have ever seen (I have ranked it first on my films of the nineties, after all, and I stand by this placement). Without needing ten hours, Kieślowski gets to the heart of both Poland and France in a story of duality. What is easily his most experimental and cryptic film, The Double Life of Véronique exemplifies fate, circumstance, and divine intervention in the span of one hundred minutes. That's it. I love when Kieślowski works big, but the fact that he accomplishes so much with The Double Life of Veronique — to the point that it feels as successful and life changing as Dekalog and Three Colours — is kind of miraculous.

Irene Jacob plays both Weronika and Véronique: two starkly different lives steered by the same soul. How would our outcomes change if we were dealt with different fortunes (or the lack thereof)? From the early shot of Weronika singing immaculately in the rain (while everyone else darts inside to avoid getting wet), I knew this was going to be a special film. With the notion of life working in opposite directions (the concept of two different seasons coexisting is a frequent one), Kieślowski confirms that time is a relative concept and that we are forever vicarious with one another; he even goes as far as making Earth both purgatory and heaven. While his other films deal with the concept of faith, The Double Life of Véronique is the one instance where we feel like we are a part of something bigger than us: a rare instance when a filmmaker was able to tap into the unknown and present it unsolved. I cannot express how much I love this film and how much it has enriched my life. It is rare for me to know I will cherish a film instantly and to have that feeling only grow right until the end of the film. This is one of the great opuses in all of cinema, and I am glad I have lived a life as a film lover where I could come across a film like The Double Life of Véronique. It was meant to be. I hope it will be for you as well.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.