Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Powell and Pressburger Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Directors

There aren’t many filmmaking duos who have truly made their mark on cinema quite as well as a couple of examples, like the Coen or Safdie sets of brothers. And then there is the pair known as Powell and Pressburger, also affectionately referred to as the Archers. I took to their greatest works within seconds. I instantly recognized that I appreciated the innovative aesthetics, techniques, and ideas that made films from the forties feel like they could have been released decades later. I saw the Archers as this unified front: practitioners of melodramatic, theatrical cinema, and students of British war stories. However, it was once I pursued as many films by Powell and Pressburger as I could muster that I understood their strengths as individuals. Michael Powell feels like the soft-spoken wild child whose art projects the eccentricities that he never gave off as a person, while Emeric Pressburger seemed to be the one who tethered Powell’s ideas enough that they wouldn’t go off the rails. As a lone director, Powell could often soar too far (but, then, we wouldn’t have gotten some of his greatest achievements if he didn’t). Pressburger allowed Powell to fly high enough without getting too close to the sun, and the end results were usually remarkable spectacles of film.

Powell started off as a gofer during the silent age of film before exploring the production process via other means, including acting, script writing, and stills photography (he would get quite the dose of experience from working on a couple of Alfred Hitchcock’s earliest films, including Blackmail in 1929). It was shortly after in 1931 that Powell was hired to make what are known as quota quickies: films around an hour long that were fast to produce and sell. Britain’s film industry was struggling in the early thirties, so British cinemas were legally required to show a certain amount of English films a year: something the quota quicky could help with. Powell would direct even up to seven films a year during the thirties before he was set to craft more substantial works, starting with 1937’s The Edge of the World. Producer Alexander Korda wanted Powell to work on a World War I espionage film titled The Spy in Black, and I will pause things here.

Imre József Pressburger had a far less hands-on approach in the early days of his career. Unlike Powell who was in the thick of film production, Pressburger was a Jewish-Hungarian journalist who fled the Kingdom of Hungary during the Nazi invasion (after every Jewish employee at UFA was laid off), moving to Paris to become a screenwriter. He didn’t find much success there and moved to England to try again (also changing his first name to “Emeric” to further his career there). After a number of years of struggle, Pressburger was hired by a producer to touch up the script for a war film since it was in dire need of improvement. Of course, it is clear that Pressburger was to help Powell with The Spy in Black. It was clear that these two were destined to meet, as they churned out two more films (Contraband and 49th Parallel) before they developed their own production company: Archers Film Productions (hence their partnership being known as the Archers). The duo would create around twenty films together.

On paper, it appeared as though Powell was the director and Pressburger was the screenwriter, but their dynamic was far more interesting than this. Pressburger would focus primarily on being a producer, Powell would bring Pressburger’s words to life, but the latter would be a part of the editing process — as well as music supervision. This relationship would mean that their visions would almost always be funded and produced via Pressburger, and that both filmmakers would have a tight grasp on what they would want to achieve. They developed what would be known as The Archers Manifesto: five rules to abide by (which clearly describe their shared mindset with all of their twenty films). This guide includes:

• “We owe allegiance to nobody except the financial interests which provide our money; and, to them, the sole responsibility of ensuring them a profit, not a loss.”

• “Every single foot in our films is our own responsibility and nobody else's. We refuse to be guided or coerced by any influence but our own judgement.”

• “When we start work on a new idea, we must be a year ahead, not only of our competitors, but also of the times. A real film, from idea to universal release, takes a year. Or more.”

• “No artist believes in escapism. And we secretly believe that no audience does. We have proved, at any rate, that they will pay to see the truth, for other reasons than her nakedness.”

• “At any time, and particularly at the present, the self-respect of all collaborators, from star to propman, is sustained, or diminished, by the theme and purpose of the film they are working on.”

This manifesto resulted in works that were ahead of their time, pushed film as a technical and narrative medium, and were made with the best intentions (and not for corporate greed). After around fifteen years of collaborations, Powell and Pressburger decided to drift apart to pursue other projects; there was no animosity, rather, both artists simply wanted to tackle different concepts. Pressburger would only direct one film by himself: Twice Upon a Time in 1953 (a film based on the novel Lottie and Lisa which would eventually lead to the creation of the better-known The Parent Trap). Meanwhile, Powell — who has worked solo and with other directors before the Archers — would continue what he once did, although his post-Archers run was not nearly as prolific as his quota quicky era. It was only the second feature film post-split, Peeping Tom, that was so taboo and upsetting for its time (given its themes on serial murder and voyeurism) that it all but completley destroyed Powell’s career. After Peeping Tom, Powell only released three more films to varying results, before reconnecting with Pressburger for two more opportunities: 1966’s They’re a Weird Mob, and 1972’s The Boy Who Turned Yellow. Pressburger would pass in 1988, and Powell in 1990; both filmmakers would fortunately live long enough to see the impact of their films, including Powell’s Peeping Tom (which was pivotal for the slasher-horror genre).

I have always wanted to dive through the films of the Archers and rank them, but something felt off. Sure, the Archers released twenty films, which was more than enough to get by with for an article of this nature. However, I couldn’t fathom not including Peeping Tom or other gems like The Thief of Bagdad and Herzog Blaubarts Burg on any list. Even though I was aware of the amount of quota quicky films I would have to sift through, I wanted to cover all of the films both Powell and Pressburger directed in total. I was more than happy to wade through hours upon hours of mediocrity, but then I stumbled into my other issue: how many of Powell’s films are considered lost. These are films that are impossible to watch because no one knows their whereabouts to preserve, restore, or digitize them. I would just skip the lost titles, but it isn’t that simple. There are a handful of films (like Powell’s Rynox, and, sadly, Pressburger’s lone solo-directorial effort, Twice Upon a Time) that aren’t completely lost but are simply not at my disposal; these are titles that have been archived at facilities like the BFI National Archive and seldom presented to the public. I can only hope to be a part of one of these lucky audiences one day, but such is not the case at this point in time.

Instead, I will work with what I have (which is, to be fair, over forty films), and I will gladly add whatever titles should be discovered or presented publicly. I technically have every single film by both Archers members which was my main objective in the first place: the rest (all of the Powell films I could watch) is extra for this list anyway. Sure, it will be tedious to go through most of the quota quickies (I won’t go too deeply into any of them), but it was fascinating to see the starting points made by a director who would become one of the great cinematic artists. When it comes to the true meat-and-potatoes of these filmmakers, there is much to explore; from whimsically profound depictions of wartime Britain, to Technicolor fever dreams. At their best, the Archers had us reflecting upon ourselves, our livelihoods, our histories, and our thoughts. There is also the whole sector of Archers-related projects devoted strictly to the arts, including some of film’s finest takes on ballet and opera. Their films are as creative as they are stirring, as vibrant as they are visceral, and as literary as they are artistically rich. Their peak works are magically timeless that are still inspiring artists to follow suit (the Archers are your favourite filmmaker’s favourite filmmakers). Now, it is time to celebrate them. Here are (most of) the films by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger ranked from worst to best.

Excluded Films That Are Either Lost or Presently Unobtainable

• Riviera Revels

• Caste

• Two Crowded Hours

• My Friend the King

• Rynox

• The Rasp

• The Star Reporter

• C.O.D.

• Born Lucky

• The Girl in the Crowd

• The Price of a Song

• Someday

• The Brown Wallet

• Twice Upon a Time

43. Smith

Quota quicky by Michael Powell

Smith comes last because it is a ten-minute-long depiction of John Smith falling on hard times; all you need to know is that the lead character’s name is, indeed, John Smith (you read that correctly). There’s very little to critique or even cling on to here.

42. The Fire Raisers

Quota quicky by Michael Powell

While The Fire Raisers has a fairly decent premise (an insurance agent who winds up getting involved with arson), it is quite forgettable outside of its scorching final scene: as if the film just frolics along until it needs to end.

41. The Queen's Guards

Solo Effort by Michael Powell

Yes, one of Powell’s proper solo films, The Queen’s Guards, is worse than most of the quickies he was churning out to get by. This 1961 film was released shortly after Peeping Tom and was a swift attempt at trying to salvage a career that was on the verge of seriously tanking. The end result is a dull drama that at least looks sharp with its colours (but that hardly matters when it winds up being Powell’s only real snooze-fest); Powell himself would dismiss The Queen’s Guards while accepting responsibility for its dismal shortcomings during a hard time in his life.

40. His Lordship

Quota quicky by Michael Powell

Another quota quicky by Powell which really doesn’t have much to care about or cling onto, His Lordship at least is an early depiction of where Powell would go as a cinematic adapter of music (but I wouldn’t put much thought into watching this film unless you were a diehard fan; it’s incredibly forgettable).

39. The Boy Who Turned Yellow

Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger

The last film the Archers ever made was this hour-long educational film: The Boy Who Turned Yellow. While a bore for young students and even a chore for adults who just want to watch the last film by this dynamic duo, I have a soft spot for the inspiration and visual splendour of this film (an effort made for the Children’s Film Foundation, so the intentions were clearly good here). I may have ranked it quite low, but it’s at least harmless to see what Powell and Pressburger thought was an effective history and science lesson (even if it is objectively quite basic compared to the rest of the surviving filmography); it’s easily the worst Archers film, but at least it is — all in all — an Archers film.

38. Lazybones

Quota quicky by Michael Powell

Once again, Powell tackles economic and class-based struggles with Lazybones: a typical film about focusing on the important matters in life that at least has the shallowest of depth (which is a win in my books when you’re looking at quota quickies).

37. Hotel Splendide

Quota quicky by Michael Powell

By quota quicky standards, Hotel Splendide is quite mysterious and even humorous (although it wouldn’t hold up compared to most other films). There are hints of the genre-bending capabilities here that Powell would be known for.

36. Red Ensign

Quota quicky by Michael Powell

You can’t achieve a lot within just an hour of runtime and with a small budget (especially if a film is rushed), but Red Ensign — also known as Strike! — at least feels somewhat full of twists and turns to be compelling enough.

35. The Love Test

Quota quicky by Michael Powell

This screwball-esque romantic comedy is typical, but seeing Powell approach it with early signs of the fairy-tale touch that his melodramas would be known for is pleasant to watch.

34. The Man Behind the Mask

Quota quicky by Michael Powell

The last of Powell’s quota quickies is amongst his messiest, but I at least find the eccentricity here more entertaining than the derivative mundanity of the weaker quickies ranked below (some may argue that the silliness and flimsiness here makes The Man Behind the Mask worse, but, again, I feel like it at least stood out which is something to me).

33. The Lion Has Wings

Michael Powell, Brian Desmond Hurst, Adrian Brunel, Alexander Korda

The Lion Has Wings is a propaganda film that is a collaborated effort by Powell and other cohorts (this is one such project where Powell worked with producer/director Alexander Korda). Outside of the shallowness and rushed tone of this film (as well as the samey feel this film has to similar features and/or documentaries), there’s a slight technical flair here that Powell and company maybe learned to pull off with their other low-budget, hastily-made productions (a test to see what they could pull off in no time at all). There’s not much else to report here, otherwise.

32. The Night of the Party

Quota quicky by Michael Powell

A whodunit film that plays by the rules of the genre; while I would have loved to have seen Powell return to this genre with more experience, time, and flair, at least this glimpse into the unknown will suffice (I do recommend it to those who cannot say no to a murder mystery, even the most obvious ones).

31. Crown v. Stevens

Quota quicky by Michael Powell

One of the better quota quickies about economic woes, Crown v. Stevens takes the concepts of hope and promise and spins them on their head when the truth comes out. Most of Powell’s quickies didn’t leave much of a mark on me, but, compared to most of the rest, this one seemed far more gripping by comparison.

30. The Phantom Light

Quota quicky by Michael Powell

Another early crime film by Powell, what I appreciate the most here is the heavy visual stakes that are present here: some sort of aesthetic artistry that elevates a decent caper story and turns it into a parade of shadows and lights; of course, Powell would make far more enriched feature films, but The Phantom Light is one of the better quicky films nonetheless.

29. An Airman's Letter to His Mother

Short Film by Michael Powell

The shortest film Powell ever made is this five-minute snippet of grief during wartime. Sure, there isn’t much to offer in a whopping five minutes (especially if there has to be voice over narration to fill in the blanks, even if it’s by Sir John Gielgud) which is to the film’s detriment, but An Airman’s Letter to His Mother is powerful enough to prove that this film had to be made: lives can change at any second, whether you’re on the battlefield or you are at home waiting for any sign (but just not that sign).

28. Age of Consent

Solo effort by Michael Powell

The last solo film by Powell is Age of Consent: a dramedy that, after Peeping Tom, tests the waters with the taboo enough to feel rebellious, but not to the point of truly mattering or causing a stir. The film features a struggling artist and his young muse (the latter played by Helen Mirren in her first major role), and we have seen flirtatious and stirring films about a creator and their subject done far better. However, I feel a candidness here, as if Powell is attempting to ask the cinematic medium to be his partner once more — even after the turmoils of the past that nearly cost him everything — and see where they could go. Age of Consent is equal parts safe yet juvenile, which makes it a bit peculiar, but the film being told by a hurt director who wanted to get things going at a gradual pace is what makes this film worthwhile for Powell fans.

27. Luna de Miel

Solo effort by Michael Powell

Otherwise known as Honeymoon, Luna de miel is proof that Powell was forever attached to how music could be represented in film (yes, even after separating from Pressburger, the music expert of the Archers). I wouldn’t go as far as calling Luna de miel underrated (because that would imply that it is a strong enough film to warrant all gazes upon it), but I would consider it a bit of a hidden gem: a colourful celebration (in both cinematography and tone) that has a freeness to it, should you be seeking such a picture.

26. Something Always Happens

Quota quicky by Michael Powell

The best of the surviving feature-length quota quickies (whatever that metric may mean), Something Always Happens is a quirky rom-com about poor choices and even harsher desires; while quite plain compared to the best of Powell’s films, this quicky at least has some personality to it (far more than the blander works surrounding it).

25. The Sorcerer's Apprentice

Short film by Michael Powell

Around the time of the dissolving of the Archers, Powell created a short film take of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. I actually quite like this adaptation but find that it ends far too soon, and would have cherished an anthological film that would have maybe incorporated this short (like The Tales of Hoffman, or, given the correlation, Disney’s Fantasia which iconically has its own take on The Sorcerer’s Apprentice). On its own, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is still sublime but it kind of wobbles on its own two feet when it was born to soar.

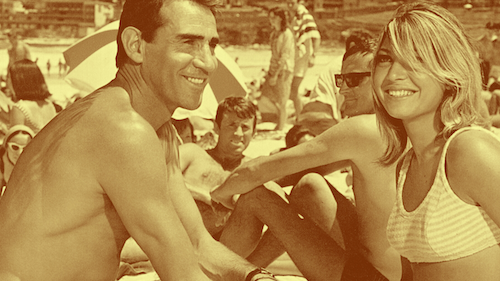

24. They’re a Weird Mob

Michael Powell & Emeric PRessburger

The penultimate film by the Archers, They’re a Weird Mob, is a fish-out-of-water comedy that is a bit puzzling. It has the visual precision of a Jacques Tati film (well, maybe not to the lengths of PlayTime) but its story is far more cookie cutter, creating a slight dichotomy between how the film feels versus how it reeds. It’s still a fun Aussie romp that doesn’t hurt to watch, but it certainly doesn’t compare with the greatest works by either filmmaker.

23. The Elusive Pimpernel

Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger

The Archers’ take on The Elusive Pimpernel is as flamboyant and theatrical as you can expect: something that would work far better for more grounded efforts like their best works (listed below). With The Elusive Pimpernel, this kind of cheese can be somewhat fun (I found it so), but I can easily see the characters and tone of the film being annoying in the eyes of other viewers; there’s also not enough boundary-pushing material conceptually, narratively, or creatively to make this film last more than the temporary good time that it is).

22. The Volunteer

Michael Powell & Emeric PRessburger

A war short similar to An Airman’s Letter to His Mother, The Volunteer feels a little more cyclical and fleshed out (being over twenty minutes compared to just five minutes may do that). I’d argue that this could have been a full feature with more to say, but we do get enough with The Volunteer that there is a sense of closure once it wraps up: proof that there’s enough substance for us to nibble on and ingest.

21. Ill Met by Moonlight

Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger

The last film made by the Archers when they were still an established duo (before the two one-off collaborations afterward), Ill Met by Moonlight is an adventurous look at Nazi-occupied Crete. The film is full of the ambition and artistry of the best Archers works, but its passion is noticeably thinner (a clear sign that both Powell and Pressburger would try to find purpose again in new ways). This film is a little slept on, and I do recommend it for fans of the Archers (but don’t expect something quite as bombastic or inspiring as what you are accustomed to).

20. Oh… Rosalinda!!

Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger

While Powell and Pressburger’s affinity for music better suited the high brow fields of opera and ballet, seeing them tackle a more traditional musical comedy is not the worst thing. Sure, Oh… Rosalinda!! may not compete with other musicals or most other Archers releases, but I do appreciate the sense of blissfulness that comes with this film: as if it doesn’t care what people think of it. It may feel a little stunted narratively (it looks great, as do most Archers films), but I think anyone wanting a fifties musical they have yet to see may enjoy themselves here.

19. Gone to Earth

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

I may like Gone to Earth more than the average Archers fan, and I understand its detractors that turn viewers off (the whimsy, the oddness, the schmaltz). I find the cutesy, fable-esque charm amusing. Then again, there is the cobbled version of this film titled The Wild Heart — at the bloody hands of producer David O. Selznick — which may be the bastardized version many people are seeing (specifically American audiences); Gone to Earth is at least stronger than this release. Even so, at its very best, Gone to Earth is only so good (that is, to say, it is pretty good): we have yet to reach the brilliance of the Archers, but we are almost there on this list.

18. Return to the Edge of the World

Solo Effort by Michael Powell

Powell was never the same after Peeping Tom (and the numerous flops or so-so efforts that ensued afterward); it’s almost poetic that the very last film he ever directed was a documentary short about one of his earliest triumphs (The Edge of the World). Powell — who is both behind and in front of the camera for this celebration — returns to the Scottish island of Hirta to reminisce on how much has changed geographically, with the cast and crew, and for him as a filmmaker. There isn’t too much here outside of honouring another feature film, but for those who want to have a bit of a personal look in the life of a private, inspirational, multifaceted individual and what can be deemed a breakthrough project for him, it is sometimes a reward to reflect on the past; I feel like this final project may have brought Powell some peace after his toughest years as a director.

17. The Spy in Black

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

The first time Powell and Pressburger worked together — on the World War I espionage film, The Spy in Black — it was as if there were instant sparks. I wouldn’t rank it amongst their top films, but The Spy in Black is certainly a successful first go by two different directors: a brooding, noir-esque thriller that focuses on the story (the narrative here is quite decent), the way this story is told (via dark — yet compelling — cinematography), and what we are told via this story (through the eyes of Brits who could tell — alongside every other citizen — that another war of this magnitude [or greater] was just on the horizon). The promise in The Spy in Black is evident, and — while I do like this film quite a bit — I am happy that the Archers’ partnership only strengthened from this point on. A solid debut for sure.

16. The Battle of the River Plate

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

If The Spy in Black kicked off the Archers’ partnership, then it is only fitting that The Battle of the River Plate came towards the end of their prime; the former was based during World War I and the latter in World War II; the former made the most of its black-and-white nature while the latter came after years of Technicolor experience. These two works are somewhat similar given their thirst for adventure and their navigation of the battleground (or vessels within it). I’m giving The Battle of the River Plate the slight edge because I think the years of work together shine through in this film more than The Spy in Black; you can sense the confidence across the board with this film. In that same breath, Powell and Pressburger also have far stronger war films than this one, but if you like the most well known titles already, The Battle of the River Plate is sure to satisfy your craving.

15. Contraband

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

It didn’t take long for the Archers to make another spy film placed during the heart of war after The Spy in Black, but, released just one year later, Contraband does what the former film does but even better (both films even share stars like Conrad Veidt and Valerie Hobson). The Archers dial up the suspense even more this time around, creating an atmosphere steeped in suspicion and doubt; of course, Powell and Pressburger would eventually become masters of melodrama, and the cracks of this prophesy do show in Contraband (rendering the film a little campy at times, but it adds to the fun, I’d argue). Maybe Powell learned a lot from when he worked as a stills photographer on Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail because the fellow British auteur’s addiction to tension is at least hinted at in Contraband: a film that could easily be confused for one of Hitchcock’s earliest talkies (well, the good ones, anyway).

14. The Edge of the World

Solo Effort by Michael Powell

We’ve finally reached the strongest films that the Archers have to offer; thank you for your patience as we trekked through dozens of films that ranged from half-baked and poor to “pretty good”. After many quota quickies, it was about time that Powell released something that was worthy of his craft, time, and imagination. Such an early breakthrough — even before he started working with Pressburger — is the poetic film, The Edge of the World. The Scottish island of Hirta is used as a metaphor for life itself, as we see the cycles of life and death upon it (to further cement how ahead of its time The Edge of the World is as a meta statement, Powell acts — and, by this, I mean he’s literally an actor playing a character — as a sailing outlier staring at a foreign land with curiosity and fascination). Hirta acts as a self-contained society, where any change will forever affect the organic and communal infrastructure (which is precisely what happens). After years of low-budget rush jobs, you can sense how badly Powell was bursting to tell something fresh and inventive with The Edge of the World: an exquisite portrait of harmony and the destruction of it.

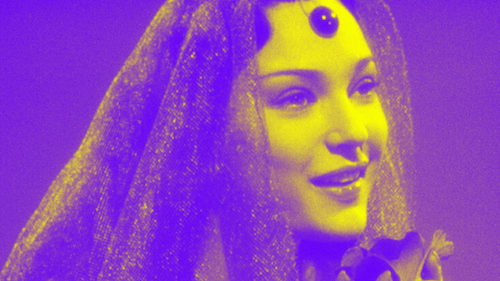

13. Herzog Blaubarts Burg

Solo Effort by Michael Powell

Not enough cinephiles discuss the brilliance of Powell’s made-for-television adaptation of Bluebeard’s Castle, but it deserves to be championed amongst his other music classics. Herzog Blaubarts Burg is a gorgeous opera that wastes no time getting you immersed with the elaborate sets and costumes of this fantastical rendition of a beloved piece; at only sixty minutes, I’d argue that this title may be just enough for those of you who cannot stomach lengthier operas (but may be curious about this film). Made after Peeping Tom was considered a disaster, Herzog Blaubarts Burg almost feels like Powell poured in everything, worried that he’d never get such an opportunity again; this results in the film feeling like an expressionist dive into the mind of agonizing souls. If Peeping Tom can get a complete reassessment, I’d like to think that Herzog Blaubarts Burg will have its day, considering it is likely the most underrated film in Powell’s filmography.

12. One of Our Aircraft Is Missing

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

World War II was well underway by 1942, and the world released a number of films in response, like William Wyler’s Best Picture winner, Mrs. Miniver. Powell and Pressburger — who, by this film, were officially going forth as the Archers — delivered one of their numerous responses with One of Our Aircraft is Missing: an intense film of survival within Nazi-occupied Netherlands. A then-harrowing look at British airmen trying to get out of their predicament (being lost and, effectively, hunted), One of Our Aircraft is Missing feels like an act of perseverance and assurance for the terrified citizens who viewed this film when it first came out. As the fighters aim to return home, we see a beautiful world photographed with the utmost care, and are reminded of what is happening within it: total carnage (One of Our Aircraft is Missing is that shred of hope that everything will be okay regardless).

11. The Small Back Room

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

Okay, so it’s another war film by Powell and Pressburger, but The Small Back Room is one of the few that is quite different from the typical fare you’d find within the genre. More invested in the psychology of a British bomb technician (character Sammy Rice) and his personal demons, The Small Back Room inspects the anxieties and traumas of a nation at war. It’s not quite as pummeling as, say, The Hurt Locker, but The Small Back Room certainly feels well ahead of its time (you’d have a strong double billing with these two works). Another underrated Archers cut, maybe there will be an audience who appreciates The Small Back Room as much as I do.

10. The Thief of Bagdad

Michael Powell, Ludwig Berger, & Tim Whelan

What I feel is a film as magical and spellbinding on a technical level as The Wizard of Oz (for their respective times, mind you) is The Thief of Bagdad (especially, if you ever get the rare chance to see it this way, on the big screen). There have been numerous adaptations of One Thousand and One Nights in film (including, obviously, Disney’s Aladdin), but — despite its age — I may pick this Powell collaboration (with directors Ludwig Berger and Tim Whelan) as my favourite version. Presented in a highly blue Technicolor sheen (perhaps where Disney got the idea to make Robin Williams’ genie a similar hue), The Thief of Bagdad feels like a projection from another reality; the ambitious special effects, sets, and costumes also achieve this sensation. Despite not being an official Archers release for obvious reasons, The Thief of Bagdad is as stunning, magnificent, and massive as anything Powell accomplished with Pressburger; it is not to be missed.

9. The Tales of Hoffmann

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

Any dedicated readers of Films Fatale may know that I am not the biggest fan of anthological films. I find the start-stop nature of a series of shorts compiled into one feature distracting and typically unsuccinct. In the case of The Tales of Hoffmann, I don’t think there are many anthology films as effective as this sterling cinematic opera. This triptych of stories all blend together like a super powered daydream, whisking you away from the world as you know it. The tales all cloud the mind of Ernst Hoffman, who is represented here as a character at the mercy of his own passions and regrets. One of the great filmic operas, The Tales of Hoffman is as transformative and hypnotic as the genre could ever get; it needs to be seen to be believed.

8. I Know Where I'm Going!

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

Some of the great romantic films come from directors who typically operate on a large scale or via a stylized gaze, like David Lean’s Brief Encounter, or Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love. An underseen entry in such a niche category is I Know Where I’m Going! by the Archers, and I want this entry to place this gem on your radar. Similar to how The Edge of the World uses the concept of an island as a metaphor, I Know Where I’m Going! places a romantic pair on two separate islands to see if their love will survive the distance (now this feels like the edges of the world). What transpires is beyond description: a take on romance that you feel, not simply witness. A precursor to works like 2015’s Brooklyn, I Know Where I’m Going! is a lovely film where the grace and passion of one’s heart is replicated by the lush nature and world around them. I wish the Archers did more straightforward romantic films like this exquisite release, because they nailed it.

7. 49th Parallel

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

Before they were effectively known as the Archers, both Powell and Pressburger released what is possibly their breakthrough feature film: 49th Parallel. Similar to One of Our Aircraft is Missing (which would be released just a year after this film), 49th Parallel is a dizzying film of survival with much involvement from external forces (like the Canadians who catch wind of this stranded U-boat, including Sir Laurence Olivier with the thickest Quebecois accent you’ll hear today). Watching everything click into place is quite the experience, and 49th Parallel is a highly calculated affair by the Archers’ standards; while their best war films veer off of the path of the genre, 49th Parallel may be the best straight-forward war film the Archers ever released (however, as great as this film is, you can only imagine how special the upcoming war films on this list are).

6. A Canterbury Tale

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

While barely linked to Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (the relation is mainly geographical), the Archers’ A Canterbury Tale is at least also a character study via a religious lens (the common ground ends there). We follow three young travelers on their way to Canterbury, England, and their quest to solve the unusual crime of “the glue man” (I’m not sure if it’ll make as much sense in context as it does out). The end result is a film that is highly neorealist yet expressionist in style and scale: a depiction of intrinsic human thoughts, emotions, and inquiries on a macro, architectural and natural scale. I feel like if this film was made by any other director, it may have been far more straightforward and simplistic, but by Powell and Pressburger during the height of their capabilities, A Canterbury Tale resonates like a soul on fire.

5. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

While far from their first film together, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp felt like the first Archers film through and through. The satirical, melodramatic tone of the film adds a layer of self awareness that heightens the generational war story here (which begins at the Second Boer War and concludes during World War II: a depiction of how combat is endless). The Technicolor here is the first instance within the Archers’ films where a film felt like it came from the future, and what a stunning film The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is. As we follow Clive Wynne-Candy through generations of combat and hypocrisy, we see a stubborn symbol of resilience through a stage-like perspective (down to the thick-enough makeup on the actors). As extreme as this film is, and as exaggerated as it may seem, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp rings true as the feeling of frustration for war and complete support for those who defend their country told via cinematographic technology that promised and preyed for a better tomorrow.

4. A Matter of Life and Death

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

How do you reinvent the war genre? In this instance, instead of showing what happens when you survive the battlefield, show what it may look like if you don’t. A Matter of Life and Death frames a Royal Air Force pilot who is meant to die but manages to stay alive; his world is in Technicolor to show an appreciation for being on Earth. However, he is eventually informed that he has to stand trial in front of a council to prove why he should remain alive when he was due to depart; this afterlife is shot in black-and-white, creating a chilling, matter-of-fact look at death (even with the swirling fantasy milieu here). With love being the main reason to keep going, A Matter of Life and Death personifies the horrors of war via a romantic, majestic fable that breaks the boundaries of one of film’s most popular and formulaic genres.

3. Peeping Tom

Solo Effort by Michael Powell

What nearly destroyed Powell entirely would eventually become the film that may have defined him for certain crowds. Powell’s hyper-aware analysis of the toxic relationship between the viewer and the subject, Peeping Tom, was more than just a precursor to the New Hollywood movement or the slasher genre. It was an uncomfortable dialogue that viewers couldn’t stomach, as if they saw themselves in the trench coat of a serial killer. Film — especially during the overly sanitary golden age — was something of a voyeuristic medium where we gawk and judge characters (who will never learn of our existence) from afar. Powell was effectively trying to turn the gaze onto ourselves and the film industry: by depicting a camera that can literally kill people. What was once seen as a failure or as blasphemous has rightfully been crowned a postmodern staple of psychological horror. Sometimes, Powell’s solo work was all over the place, but, occasionally, his determination and eccentricity would bring the world something untouchable, like the once-maligned, now adored Peeping Tom.

2. Black Narcissus

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

If Peeping Tom was Powell going too deep into the cynical darkness of humanity, then Black Narcissus was as bleak as both Archers ever got while working together. What starts off as a lush dreamworld in the Himalayas — with a miniature community of Anglican nuns and the village’s locals — slowly descends into an erotic — nay, psychotic — series of addictions and hysteria. By the end of this Technicolor nightmare, Black Narcissus is not the same as when it started, concluding with full-on images of terror and heightened delirium. The shifts are so gradual and sleek that they are difficult to pinpoint upon a first watch. I cannot emphasize how daring Black Narcissus is for its time, as if it vowed to pull a bait-and-switch trick on unsuspecting audiences (then again, that is the very point of such an analysis: to remind us that anyone can succumb to the deepest depths).

1. The Red Shoes

Michael Powell & Emeric PressburgeR

I often find that the best films in any director’s career is a proper culmination of all of their strengths; I don’t aim to feel this way, I just feel as though this is frequently the case. With Powell and Pressburger, this claim is no different (outside of not depicting war at all: a clearly common theme for the Archers). The Red Shoes is as marvelous as Technicolor films ever got (to me, this is the Technicolor film of all time), with some of the strongest cinematography in all of film. The fairy-tale elements render this melodrama a tale that exists in both reality and in our minds: a blurring of what we live versus how we feel, especially within the realm of the arts. The focus on music here is at an all time high; while not an opera, The Red Shoes feels akin to The Tales of Hoffman and Herzog Blaubarts Burg with how they transport us to dimensions of pure aesthetic and theatrical splendour.

We follow an impresario who dreams too high and a ballet dancer who only wants to be perfect, we see those who push themselves too far for their art: a claim that, maybe, the Archers are saying isn’t so. By crafting their most daring, bold, and glorious spectacle with The Red Shoes, it’s as if these two were willing to go down with their ship: a film that embodied their manifesto through and through, no matter what the end result was. Fortunately, unlike some of the Archers’ works that were too forward thinking for then-contemporaries to catch up, The Red Shoes was adored when it came out; sometimes it is impossible to shun what is clearly an instant classic. Between the exemplary artistry, outstanding choreography, mind-boggling cinematography, committed performances, and dazzling direction, The Red Shoes is as perfect as music-based cinema can ever get; I also believe it is the greatest film of the 1940s. I also believe that it is the greatest film Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger ever made.

If you would like a tidier recap of how I would rank solely the films by the Archers as a duo, see below:

20. The Boy Who Turned Yellow

19. They’re a Weird Mob

18. The Elusive Pimpernel

17. The Volunteer

16. Ill Met by Moonlight

15.Oh… Rosalinda!!

14. Gone to Earth

13. The Spy in Black

12. The Battle of the River Plate

11. Contraband

10. One of Our Aircraft Is Missing

9. The Small Back Room

8. The Tales of Hoffmann

7. I Know Where I'm Going!

6. 49th Parallel

5. A Canterbury Tale

4. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

3. A Matter of Life and Death

2. Black Narcissus

1. The Red Shoes

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.