Black Narcissus: On-This-Day Thursday

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For May 26th, we are going to have a look at Black Narcissus.

Last week I discussed Michael Powell's solo risk with Peeping Tom: a film so ahead of its time, it destroyed his career. Powell used to be a half of the Archers partnership, along with Emeric Pressburger. What is curiously coincidental is that a week after Peeping Tom was released, it was the anniversary of the theatrical debut of another film by Powell; this time, it was with his partner in crime Pressburger. Peeping Tom was Powell venturing into the dark alone. This was too much for audiences.

May 26th 1947, Black Narcissus was released. It was Powell and Pressburger entering the dark together. The distribution of weight made for a much more digestible film. However, that does not make Black Narcissus any less shocking. If you recall last week's review, I brought up how The Red Shoes dipped its toes in the lake of the dark side. Its climax is one that was surely nerve-wracking for its time. I resisted to bring up Black Narcissus. I restrained to for an entire week. This is because today is the opportunity to discuss it. Today is the day we dive right into a strong contender for the greatest melodrama of the golden years of cinema.

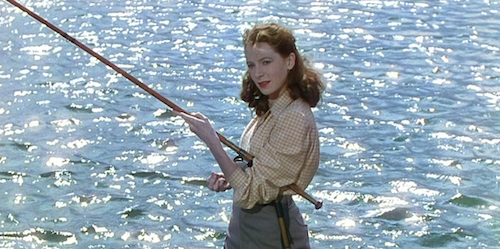

I firstly find the "erotic" label this film gets a bit strange. Sure, a portion of the film deals with its subjects (mainly nuns that are sent to a remote part of the Himalayas) falling into a well of lust. Yet, that is hardly erotic. I think erotic films have a connection with their audience, as if they are lured in such a way. In ways, sure. The audience here is caught under a similar spell. The cinematography (easily in my “top ten of all time” list) is still absolutely sensational. I can't even imagine what it was like in 1947. This effectively makes you feel the hypnotism of the land: the very kind that gets brought up by characters in the film. Pink flowers. Blue skies. Radiant waters. Luscious greens. You will wish you were truly in this film.

The shimmer on the water is so strong in this shot, it’s actually somewhat difficult to look at dead on when it is in motion.

However, this is the cut off point. To return to my argument (and not prove the lure of the film), there is a major disconnect between us and the actual characters, in a way that (for me) slots this film under the "psychological horror" category instead. We see changes in leading characters, but the dramatic irony is strong. Black Narcissus is like the psychological turmoil found in a story like The Lord of the Flies. The difference here is that the nuns are not stranded. There is no true suffering. There is only the idea that something nefarious is meant to happen. That makes Black Narcissus such an intriguing film. How much of this film is hinged on the anxieties of the main characters? I would argue a great deal.

Sister Clodaugh (played by Deborah Kerr) is recovering from a hurting romantic split. It was a large reason as to why she entered the sisterhood in the first place. Already, you can tell that her inclusion in this tale is a mental battle. She yearns to be the best for God and for the people of the Palace of Mopu, but the crack in her armour widens. This is thanks to Mr. Dean (David Farrar) being tossed into the equation: a possible redemption. Dean is a troubling and lethargic character that is self centred. Clodaugh fights against him at first, and this catches the attention of Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron), who is enduring her own battle: the desire for a better life.

Sister Clodaugh acts as somewhat of an anchor, even when everything seems to be okay (when they really are not).

The film bounces between points in the love triangle, and it plays a very safe game. That is until the final act, when all hell breaks loose (almost literally). This is when the film truly becomes a melodrama. Finally, the subject matter has caught up with the strength of the rich colours. This is a mind cracking. It almost comes from out of nowhere the first time you see Black Narcissus. This was all foretold, though, by a tale brought up by The Young General (Sabu), of a force that works it's way in.

Considering The Young General's subplot with his affections towards a dancer stricken with poverty (Jean Simmons), there might be a bigger picture at play here. Clodaugh being Irish and Dean being British may not have been arbitrary. It is implied -- and interpreted -- that Black Narcissus was heavily shaped by the British observations of both India and Pakistan at the time; this includes the debating of moral and religious principals. The world we see in Black Narcissus is beyond description. Yet, it turns into a land ravaged by despair. It suddenly feels empty, and it's all due to the self despairs of the characters we see.

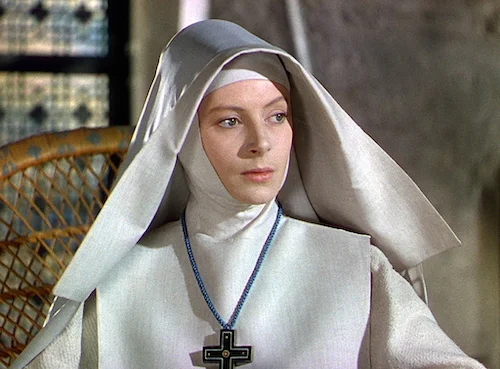

Sister Honey representing a harbinger of things to come.

The Young General also aspires to learn, and we see traveling classes trying to put together English phrases as well. Perhaps this is an indication of a common ground that people may share when differences are put aside, and cultures are truly embraced. The Palace of Mopu is treated as a negative assignment by Sister Clodaugh (especially since it is her first time being Sister Superior), so we were doomed from the get go. So much of Black Narcissus is the intrusion of a force that simply does not exist, and it's baffling to revisit every time I watch this film.

Sister Ruth during the final act of the film.

It's all in the title, at the end of the day. Black is the removal of all colour, and Narcissus is the complete focus on one's self. Nothingness meets everything. White habits cloaks enter a world of pinks, blues and greens. Some get stained with blood. Some turn black entirely. Mental struggles enter a literal place, where people live each day as it comes. This is a fight to the death that never was. Knowing all of this does not make the climax any less challenging, though. With the greatest use of Technicolor, and the most heightened of orchestral scores, we fear the plunge more than anything. There is such a height that we still have to fall from, despite hitting the very bottom already. It all ends suddenly. All we can do is travel through the rain and contemplate. That's exactly what Black Narcissus does. It can't really wrap up a film this risky for 1947, and so it doesn't bother to do so. Considering the themes, visuals, and climax, that somehow is the largest risk Black Narcissus took for a film released in the '40s: an ending with no bells or whistles, but instead a fade into eternity.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.