Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Mike Nichols Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers who have made our Wall of Directors (and other greats)

Igor Mikhail Peschkowsky was a tour-de-force of many forms of entertainment. You may know the German-born legend by his stage name, Mike Nichols: a moniker that has stood the test of time. Despite his impact on film, Nichols’ background is quite different from being a budding cinephile at a young age like so many auteurs are. If anything, Nichols was a student of the stage who aspired to undergo the strenuous lessons of method acting during the fifties (when the performance style was truly taking off). Having struggled to make it big as a theatre actor, Nichols eventually crossed paths with another budding star, Elaine May; this eventually led to the union of one of comedy’s great duos, Nichols and May. The pair’s fondness of improvisational acting and witty writing resulted in game-changing material, but the two boasted such promise that their once acclaimed performances and albums almost feel faint compared to what each of them would later achieve. They split as swiftly as they converged, however, once pressure and tension built up between the two of them. Nichols utilized his new stature to return to the stage where he became a Broadway juggernaut; however, his expertise arrived in the form of directing for the stage, not acting upon it.

He was suddenly a sought after name in New York, so much so that the demand spilled over into film. He became the go-to director to work with on Broadway (three Tony Awards for Best Direction of a Play in two years, for Barefoot in the Park in 1964 and both Luv and The Odd Couple in 1965, may do that); it was only a matter of time that he would be requested elsewhere. Both Elizabeth Taylor and Warner Bros. Entertainment wanted Nichols to handle the film adaptation of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? despite not having a film background; this didn’t matter, seeing as the film was a box office success, an awards season behemoth, and one of the flag bearers for the New Hollywood movement. Nichols proved to be as prolific in film as he was in theatre, quickly releasing his sophomore feature, The Graduate, one year later. The film catapult a then-unknown Dustin Hoffman (who shared Nichols’ affinity for method acting) into the stratosphere; The Graduate also nurtured the New Hollywood wave that was becoming unstoppable in 1967. Nichols would win Best Director at the Academy Awards for The Graduate, marking the last time a film won simply for its direction and nothing else (that is, until, Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog nearly fifty-five years later).

Nichols became a poster child for a new, ruthless form of American cinema, predating New Hollywood champions like Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Steven Spielberg (amongst others). While Nichols’ films didn’t hold back on swearing, eroticism, addiction, or pure, raw, human vulnerability, he wouldn’t remain a taboo filmmaker for long, as he would exercise his capabilities in other genres and styles; by the end of the eighties, Nichols was a softened director who wanted to find the light within people and not just the urges and complexities that make them tick. Thanks to his illustrious past, Nichols was quickly an EGOT legend (EGOT winners are those who have earned at least one Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony), with three of his awards having been from the start of his career (he earned an Emmy with Elaine May during their comedic partnership for Best Comedy Album for the release An Evening with Mike Nichols and Elaine May). However, while the three other awards happened in the span of just five years (1962 to 1967), his elusive Emmy awards would finally happen at the turn of the twenty-first century, winning for his television projects Wit and Angels in America. Considering the amount of awards and the magnitude of what he won for, I’d argue that Nichols possesses one of the most impressive EGOT portfolios of all time.

After a highly busy career, Nichols passed away in 2014 from cardiac arrest. His passing was an illuminating one. I will never forget how many different forms of remembrance out-poured from all over the world. Usually, an icon would have many people grieving over certain achievements. With Nichols, it was different, not just because of how many entertainment industries he dominated but because of how versatile he was even within them. Asking someone their favourite Nichols film almost feels like a litmus test of what kind of cinephile one is. Is one a passionate film student obsessed with The Graduate; the deeper movie buff who prefers the lesser-known Carnal Knowledge; the rom-com straight shooter who likes Working Girl; the prodigy of film in the internet age via Closer; the traditional awards season dramatist with Silkwood; the fun-loving go-getter with The Birdcage. The list keeps going.

It feels easy to try to limit what makes up Nichols’ style, but I assure you the late director only made his approach feel effortless. Sure, one can point out how he is one of the best filmmakers when it comes to getting the most out of his actors, seeing as many now-high-profile names turned in some of their best work under Nichols’ direction. I’ll go one step further and say that it is through Nichols’ films that we saw new stars being born (Hoffman, Alan Arkin), veterans have renaissances (Taylor), non-actors become mainstays (Cher, Art Garfunkel), and rising actors do the necessary pivots to remain vital (Jack Nicholson, Natalie Portman). Numerous actors worked with Nichols time and time again: a testament to how brilliant he is to work with. However, diluting his capabilities simply to how he works with actors is unjust. Nichols’ love of saturation — particularly his fixation with pale, sea-foam blue — blessed every shot. His quest to toy with focal points (either with close-ups, or with having numerous subjects on screen at once in complicated builds) felt like his acknowledgment of what film can offer over Broadway. The brief moments that cuts act unruly, allowing how Nichols’ films are edited to break up the flow he previously instilled. Whether he was experimenting or working via traditionalism, Nichols was always fascinating.

This is true even with his worst films; there are a couple of titles I would deem not very good (but none are, say, atrocious). Nichols always had something to say and new ways of trying to say them. Not every project work, but most of them did. Having said that, I have found that even some of the films I have ranked lower on this list have their fans, proving my point above: that Nichols’ versatility meant that every film lover has a different relationship with him. Despite all that I have said, it almost weirdly feels like Nichols isn’t quite as respected as he should be. Sure, some may point to specific films of his that worked and applaud them, or comment on his place in cinema. After catching up with every film of his I could watch (all that is missing is his short film — Teach Me! — which is likely lost), I feel like Nichols should be as esteemed as many of the peers he influenced; from the New Hollywood disciples that came after him, to even the mainstream filmmakers who furthered his mission. Nichols is respected, loved, and acknowledged, but I also think that he should be considered amongst the greats. I hope my ranking below justifies why. To me, Nichols could basically do it all, and I feel like some of his oversights would have been corrected had he still been with us today. For now, I will focus on what we have: twenty one projects who feel like they came from twenty one different directors (I am including both of the television works he directed). Here are the films of Mike Nichols ranked from worst to best.

21. What Planet Are You From?

While not the worst comedy film I’ve ever seen, What Planet Are You From? is certainly Nichols’ weakest film. His first film of the new millennium, this science fiction comedy is meant to play like a satire on the oddities between men and women in romantic relationships, including what bearing a child may mean to different people. Some of that commentary soaks through in the form of decent performances (Garry Shandling is fully committed as an alien pretending to be a human), but What Planet Are You From? is otherwise too mediocre, too stale, and too shoddy to work to its fullest. I admire what was attempted here but don’t really care for the end result (especially the half-baked conclusion).

20. Heartburn

What is meant to be an unlikely pairing between two very different types of writers who link up (played by Nichols mainstays Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson) winds up being an uninspired misfire. Heartburn is at least far more normal on paper than What Planet Are You From?, but I think the execution for this film is not nearly as fiery, bombastic, and electric as it should be. Instead, Heartburn plays it a little safe, which is not what I want in a film that is about lovers butting heads. At least — in typical Nichols fashion — the lead performances have enough chemistry to give the film somewhat of a pulse.

19. The Day of the Dolphin

I actually want to defend The Day of the Dolphin because, shockingly, I actually quite like this film. I can also admit that it is quite strange, cheesy, and clunky, but I cannot help but admire how much work and thought was put into a film about a scientist who wants to teach dolphins how to talk (if that isn’t strange enough, the scientist is played by George C. Scott post Patton). This film should not look as great or feel as moving as it does. I’d actually fight for The Day of the Dolphin if it wasn’t for one major factor: how ridiculous the film gets in its third act. Still, I have a soft spot for this peculiar film and feel more of an inclination to watch this than some of the Nichols films I have ranked higher than it. Maybe I’m just easily amused and love dolphins. Who knows.

18. Regarding Henry

While The Day of the Dolphin tries hard enough to feel like it tries too hard to the point of silliness, Regarding Henry is a different kind of kitschy: a very plain kind. J. J. Abrams’ screenplay aims for you to feel sad throughout this drama about a lawyer recovering from being shot; even Hans Zimmer’s score is uncharacteristically corny. However, Regarding Henry does have a far more stable premise and execution that it at least feels far less flawed than the films I have ranked below it. I do find it unimpressionable, though, even though Regarding Henry is all but begging for your sympathy.

17. The Fortune

Nichols tried to use his New Hollywood platform to bring us back to the roaring twenties with The Fortune: an attempt at making a neo-screwball comedy that doesn’t quite work. Some of the jokes fall flat, and the murder plot feels thin as well. However, The Fortune does have one thing going for it: Jack Nicholson and Warren Beatty understanding the assignment. The bickering between these two cartoonish buffoons makes up for the whole film; while I wanted The Fortune to end, I was always happy to see these two leads going at each others’ throats (which happens incredibly often). I wouldn’t call The Fortune a good film, but, thanks to two great actors who got their starts during the New Hollywood movement, I would at least call it entertaining enough.

16. Wolf

I would have loved to have seen Nichols tackle the horror genre again, because it feels like the one genre he attempted that he didn’t quite nail the first time around. Having said that, Wolf is actually a decent attempt at trying something new within the confinements of horror, down to trying to find a romantic angle within it. Some of the effects are dated by today’s standards, but I think there is enough aesthetic splendour going on in Wolf that I respect what Nichols is trying to do with it (almost as if it is his version of Coppola’s Dracula, while not being nearly as good, of course). Wolf could have been a mockery of the horror genre in the hands of another director, but Nichols turns what could have been a farce into something kind of endearing and oddly sentimental despite the darkness (and, obviously, the whole werewolf thing).

15. Biloxi Blues

While other war-based films were getting rawer and meaner, it almost feels antithetical that Nichols aimed to be sweeter and more hopeful with Biloxi Blues: a dramedy that doesn’t really nail the highs and lows of its subject matter but at least feels steadily warm and charming. If you want to see a war film done in an unorthodoxically sweet way — without ever feeling insulting or misguided — then Biloxi Blue will at least deliver that. Otherwise, despite its niceties, I’d only go far to call this film “fine”, and essentially unremarkable outside of a satisfactory performance by Christopher Walken as Sergeant Toomey (under Nichols’ guise, Walken doesn’t fly off the rails in this role).

14. Gilda Live

From this point on, I’d consider the rest of Nichol’s filmography strong enough to consider checking out the following releases. I usually don’t include comedy specials on these kinds of lists, but I feel like Gilda Live warranted a mention. Firstly, Nichols’ background was in comedy after all, so seeing the director return to that realm — albeit from behind the camera — was interesting. I also think that Gilda Radner’s set is so creative with its moving backdrops and imaginative props and costumes that there certainly is a filmmaker’s eye as to how all of this comedy special was captured; Nichols’ involvement with Radner’s material was likely next to nothing, but his framing of the comic enhances her at every instance.

13. Primary Colors

While Nichols would work with Aaron Sorkin on Charlie Wilson’s War, I almost feel like Primary Colors was an attempt at making a Sorkin-esque film (this was written by Elaine May, who would reconnect with Nichols on numerous projects well after their split as a comedy duo). As a roman à clef about President Bill Clinton’s run for office in the early nineties, we get almost the two halves of Nichols — the ruthless New Hollywood style of commentary, and the sentimental introspection of what makes us human — melded together. The end result is a fairly interesting look at the peculiarities of American politics, and both the clownishness and sincerity that stems from those who want to make their country a better place (even if they are misguided). Additionally, perhaps it is Nichols’ guidance that makes John Travolta’s “Clinton” (named Governor Jack Stanton here) an endearing caricature.

12. Silkwood

I find Nichol’s straightforward biographical picture, Silkwood, mostly gripping thanks to the trio of fine performances from Meryl Streep, Cher, and Kurt Russell (the latter two were risks for their time, seeing as a singer and an action star were now meant to be taken seriously as dramatic co-leads; we never doubted them again afterward). Nichols’ muted-yet-gritty direction of this depiction of union activist Karen Silkwood’s life is compelling enough that I stick with the film throughout its entire runtime; that is to say that the film does feel overlong which is its only main vice. If it was a bit tighter, I believe Silkwood would have drove its points home even more directly. As it stands, this is still a powerful look at perseverance and the lengths that crookedness will go in order to stifle justice.

11. Working Girl

Rarely does an auteur dip their toes in the well of the romantic comedy and come back unscathed, let alone actually create a great film. Nichols pulls off the unthinkable with Working Girl: a no-nonsense rom-com that never feels pretentious or as if the work is beneath a director who is more accustomed to more challenging material. If anything, Nichols champions all who are on screen to be the best versions of themselves, including star Melanie Griffith who holds her own against some of Hollywood’s biggest names (Harrison Ford and Sigourney Weaver). There’s also a lot more going here than just romance, seeing as Griffith’s Tess McGill represents the everyday employee and women worldwide when she succeeds in realms that aimed to keep her out. As standard as Working Girl appears to be on paper, like Nichols’ directing style, it is far more multifaceted than it leads on.

10. Postcards from the Edge

There is much going on with Postcards from the Edge. Meryl Streep and Shirley MacLaine are phenomenal as a dysfunctional daughter and mother who air their vices out in the open. Carrie Fisher’s candid screenplay is just as unapologetic and authentic as the Star Wars legend was in her everyday life. Then there is Nichols using the blurred lines of the screenplay — from film to reality; from drug addictions to a lust for life — as a means of creating a borderline meta ambiguity throughout Postcards from the Edge. The end result is a dynamite feature film whose infectious nature will seep into your soul; you can almost feel the fizz of this film’s bubbly nature on your skin.

9. Charlie Wilson’s War

Nichols’ final feature film is the underrated political drama Charlie Wilson’s War, penned by the great Aaron Sorkin. Directors either try to enhance Sorkin’s dynamic writing style’s energy (see David Fincher for The Social Network and Danny Boyle for Steve Jobs) or they strive to capitalize on the heart of his writing via over-sentimentality (Rob Reiner and A Few Good Men and The American President, and Sorkin himself with all three of his own directed films). Nichols is one of the only directors — like Bennett Miller and Moneyball — to rest in between both approaches with a film that is as human as it is theatrical. The end result is a pulpy approach to political affairs that dials down on the severity of Operation Cyclone while also pointing out the oddities found even from those whose choices will dictate the fate of the world.

8. Catch-22

One of my favourite novels is Joseph Heller’s Catch-22: a satirical text on the damnation and absurdities of the age-old practice of sending men to die for their country. I feel like the novel is borderline impossible to adapt directly; believe me, many have tried. Nichols teams up with his frequent collaborator, Buck Henry, for a film that is not an exact replication of Heller’s novel but, rather, an extension of its ideas in its own way. The end result is one that may not have won the fight against Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H but has aged far better than many may have deemed upon release. The use of repetition, comedy within tragedy, and seriousness within stupidity helps Catch-22 feel elevated and privy to how we read cinematic satire today; Nichols also had no reason to go as hard artistically as he does with what could have been a slapstick bonanza. The flight and fire sequences are some of Nichols’ most impressively directed achievements, which feel like extra reasons to watch Catch-22: a film that I feel like is far stronger in execution than initial reviews would lead you to believe.

7. Closer

I have always liked Closer but haven’t quite loved it until I went through all of Nichol’s filmography. I first saw this film as a basic look at love triangles and heartbreak via four strong performances who interlock with one another. I understand the hidden rebellion within the film now, since I was able to recognize that none of Nichols’ films ever feel like they are truly playing by the rules. Such is true also for Closer, which — upon further inspection — is a traditional romantic drama in costume only. Instead, these are four cries for help found within a genre that will only give you the answers you crave, not the ones you need. I see a tug-of-war between the film we see and the writing underneath it: as if reality and fantasy are not one and the same here. Appearances are not everything in Closer in more ways than one, and I now find this deception quite alluring and earnest (ironically).

6. The Birdcage

Nichols and May’s adaptation of La Cage aux Folles is so great that it may be the definitive version of this story that I have ever seen (yes, this includes even seeing an on-stage version of it in person). Nichols never goes overboard with flamboyancy or his message in this LGBTQ+ dramedy, understanding how far he should take his tones and themes with just the right amount of vibrancy. We also see great performances from Robin Williams, Nathan Lane, Gene Hackman, Dianne Wiest, and more; the world is their stage, and they make the most of it (even with the limited setting, which never feels like an inconvenience here). The end result is a romp that is hilarious, lively, and unforgettable.

5. Wit

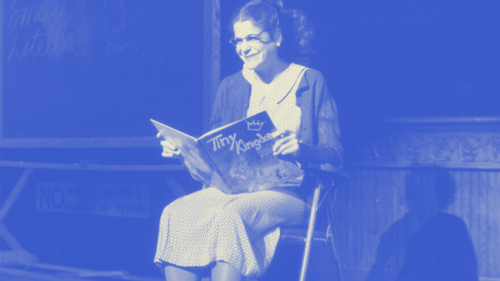

Nichols’ first course of action when it comes to directing for television is the magnificent adaptation of Margaret Edson’s play, Wit. Centered by a breathtaking performance by star and co-writer Emma Thompson, Wit details the final days of a professor’s battle with cancer (Wit also marks a rare time when Nichols worked on the screenplay for one of his films). Instead of relying heavily on the stage-like qualities of Wit, Nichols helps turn this mainly one-woman show into a series of internal monologues, broken fourth walls, and meta analyses, creating a major bond between Thompson’s performance and her arrested audience. Wit proved that Nichols was meant to be on the small screen as well, and I am glad that he didn’t stop there.

4. Carnal Knowledge

The heaviest Nichols ever leaned into the taboo nature of the New Hollywood movement is with the sex-crazed dramedy Carnal Knowledge; it’s no wonder that he released one of his softest films, The Day of the Dolphin, instantly afterward (perhaps as a palette cleanser). Yet there is still restraint shown in a film about two men trying to achieve sexual conquest with the unsuspecting women around them; while other filmmakers may have doubled down on the depravity and eroticism of such a topic, Nichols is more interested in the ways that sexual obsession is detrimental and harmful to one’s self. We see the dilemmas posed between the lead characters, played by Jack Nicholson and a surprisingly terrific Art Garfunkel (whose music, alongside partner Paul Simon, was used in The Graduate only a few years earlier). Garfunkel’s Sandy vows to grow out of his urges and find love, while Nicholson’s Jonathan finds purpose in his conquests. Maybe Nichols was commenting on society’s fixation on sex and fetishization with Carnal Knowledge and separating its followers in two camps: those aware and hoping to heal, and the unaware who think they are in full control (when they can’t even get a handle on themselves).

3. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

One of the great directorial debuts in all of film is Nichols’ relentlessly tense adaptation of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?: a late night double date from hell. We see a disgruntled couple — played by then real-life spouses Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton — inflict and infect a younger pairing with their toxicity (the latter are played by George Segal and Sandy Dennis). For over two hours, this film is a tightrope walk where the ground beneath you plummets deeper and deeper down; the stakes only increase with each sharp-toothed insult and backhanded compliment. Not once do I notice how limited the locations are, how small the cast is, or how much dialogue there is. I am instead mesmerized by this extreme depiction of guilt, hopelessness, and heartbreak. Some directors luck out with their first films; Nichols proved he was a master of the big screen in one shot with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?.

2. The Graduate

One of the most pivotal films of the New Hollywood movement, The Graduate is more than just a film about Mrs. Robinson (the seductive groomer who preys on Benjamin Braddock). Here is a vision of an aimless young-adult who still feels like a child in search of life’s answers; by the iconic final shot, he will find that, even once he finally takes charge of himself and his choices, he will only be more lost than he’s ever been. That’s adulthood, and we will only be more confused as we get older. Despite being a film about existentialism, Nichols feels completely in control of his vision here, with some of his most stylized filmmaking choices he would ever make. It would be the film that would define his career, and rightfully so: The Graduate is a near-perfect look at isolation, desperation, and desire. It would be the greatest feature film that Nichols ever directed. However, it doesn’t take an eagle eye to note that we haven’t reached the end of this list yet…

1. Angels in America

While it feels like cheating to include Angels in America — a miniseries — here, I do believe that this is a lengthy film that was cut up in episodic format. Nichols himself would agree and would crown Angels in America his magnum opus. I’m not agreeing for the sake of agreeing with the late director; I don’t believe in blindly nodding my head to anything my favourite filmmakers may say (believe me, I often don’t see eye-to-eye with everything that they say). I agree because, in this instance, Nichols is right: Angels in America is the greatest thing he directed on screens both big and small. Tony Kushner’s play gets turned into a nearly six-hour epic that shows interlocking stories of the many lives afflicted by the AIDS epidemic of the eighties, from famous names (lawyer Roy Cohn) to everyday people introduced to us via this vessel. With numerous actors taking on multiple parts (like Nichols veterans Emma Thompson and Meryl Streep, but also a tour-de-force set of performances by Jeffrey Wright), Angels in America finds unity between all walks of life; between those still with us and those in the afterlife.

The effects of this miniseries are quite dated, but that only goes to show how powerful and magnificent Angels in America is: I couldn’t care less about these effects. I get tears in my eyes every single time. I never want this miniseries to end (I did crown it one of the greatest of all time, after all; as per my rankings, I consider it the greatest American miniseries). With how long it stays in my heart and soul, it feels like it never actually does end. Kushner’s writing soars, and Nichols has never been better (including the enhancement of the already stellar screenplay). Nichols operates at another level here with more lead performances than ever before, more stylistic risks and ideas (and for longer periods of time), and the largest amount of empathy from a director who has always worn his heart on his sleeve. From his background in method acting and improvising new ideas, his rise on the stage and in film, and his eventual migration to television, it truly feels like all of his career led to this very moment. It shows with a majestically massive film that never loses sight of what it is trying to say, what style it possesses, and how many people it can affect with its message. Angels in America is the greatest film Mike Nichols ever directed. If you would rather point out how this is a miniseries, how it’s too long and how you don’t have the time for it, that onus is on you; I’m here to remind you that this is an American masterpiece.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.