Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Terrence Malick Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Directors

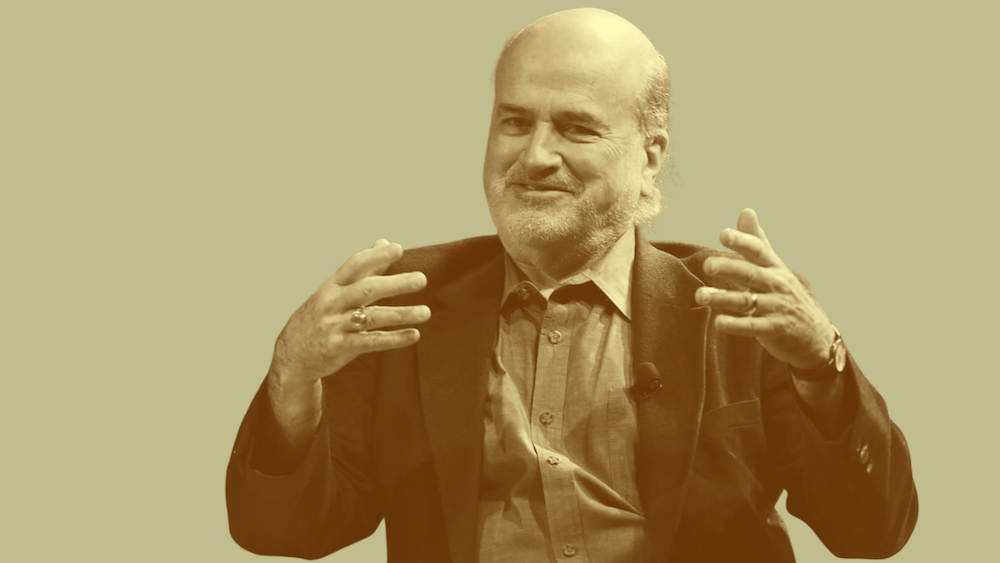

Of all of the visionaries who emerged out of the New Hollywood film movement, the one who nourishes our souls the most is Terrence Malick. The highly private Illinois native is known for his aesthetic, poetic, transcendent films that feel like the memories and internal thoughts of others that we are being graced with. To watch a Malick film is to experience cinema that can change you as a human being. This transformation can be attributed to Malick’s expertise in philosophy, having taught the subject at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (while he didn’t graduate with a degree in philosophy when studying at Oxford, Malick did graduate from Harvard with a Bachelor of Arts). With that in mind, I appreciate how Malick’s films — despite their theoretical nature — are never preachy. We are welcome to search for our own purpose amidst Malick’s introspection. Through some of the best cinematography of all time (via the partnership with masters like Emmanuel Lubezki, John Toll, and Haskell Wexler, amongst others), Malick’s films invite you to venture into deep images that swirl around you — all while connecting you with lost souls via extreme close-ups and sharp angles (usually facing up at our subjects). No matter what story we are watching, Malick’s films always make us feel like life is speeding past us as we are frozen in a limbo or crossroads: what will our next move be?

Of course, Malick’s output wouldn’t have been possible if he wasn’t as particular as he is. Infamous for his tremendously long post production processes, the adage that a new film — different to the one shot — comes out of the editing room couldn’t be more true for Malick. This has resulted in the occasional bitterness of actors who have sworn that they delivered some of their best work, only to be resorted to a sound bite, a brief shot, or some other form of anecdotal reference. I understand the frustration, but Malick’s films feel like the tapestries of consciousness, and it is hard to ignore the magnificence of these end results, no matter how these films were conceived. Malick’s filmography is also strangely mapped out, considering that he released two films in the seventies, had a twenty-year hiatus until The Thin Red Line in 1998, and became oddly prolific in the 2010s (in his own glacial way, of course), churning out six films in this decade alone (amassing for over half of his entire filmography).

It goes without saying that Malick marches to the beat of his own drum and operates specifically how he desires. He rarely makes public appearances, let alone partakes in interviews. He has ten films over the course of a fifty-year career. His 2010s work is notorious for their polarizing, experimental styles: a path that had many critics and viewers questioning his methods and concepts. With all said, Malick is a highly accoladed artist, having won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, the Golden Bear at Berlin, and many other trophies (despite three Academy Award nominations, how Malick doesn’t have a single Oscar win is baffling). I will also add that I don’t believe that he has a single bad film. Nay, not even a single mediocre film. I love every single one of his motion pictures and would easily consider Malick to be one of the greatest minds in all of American cinema. Having said that, I will still rank his filmography, but consider the lowest his “least good” film, not a sign of poorness. I wholeheartedly recommend any of his films to those who are curious to watch them. Here are the films of Terrence Malick ranked from worst to best.

10. To the Wonder

Yes, it should come as no surprise that To the Wonder is placed last. As much as I love the film, it is easily the weakest Malick film mainly because it has the most flaws. Some of the casting choices raises questions, like Javier Bardem’s brief part as Father Quintana (who doesn’t quite give off the depth that the role requires). Malick’s films are usually narratively spacious, but To the Wonder may be a little too spread thin. Despite all of this, I feel like there is enough personal cadence here to feel the heartbreak and isolation that is ever present in a film that ponders where a failed relationship went wrong. It is this bareness that elevates the film, and, in a sense, amends the imperfections; a film as broken as the relationship within it feels oddly cathartic. To the Wonder is still gorgeously shot, highly moving, and a quest for fulfillment. It sticks its landing because it never gives up its search for purpose.

9. Song to Song

The other film that is frequently brought up as Malick’s worst is Song to Song, but I think it is more complete than To the Wonder. Part of this is the stronger focus on what it is portraying: likening turbulent lives and romances to the hustle and bustle of music festival circuits (in this instance, particularly the Austin, Texas scene). As someone who used to be a concert journalist and photographer, I speak (well, spoke) the language of music festivals: the exhaustion of long days and little rations underneath the beating sun, the jubilation of watching live acts perform, and the unification of crowds (we are all strangers, but not when we are all connected via music). The separate lives that intertwine in Song to Song are handled well enough that I found myself caring about the various twists and revelations as they would come, and the stages of life here are shown as if they are songs in a set (hence the title of the film, I suppose). I found the narrative as fascinating as the documentation of live musicians (real or acted), and, as a result, Song to Song has a special place in my heart. Some may find this film dull. I find it enchanting.

8. Voyage of Time

Despite the documentary-like elements in some of Malick’s other films, Voyage of Time is his sole documentary in its purest nature. Having said that, it is hardly different from his narrative features; if anything, it feels like the sequence in The Tree of Life (the one showing the start of the universe, dinosaurs and all) was a test run so Malick could commit to this concept fully. Voyage of Time is not just the showcasing of the birth of Earth and the majority of its natural evolution (including a hypothesis of what the end of the world may look like in a astronomical sense). It also displays these images via constant movement, truly selling the idea that this is a voyage (like the title states). Now, there are two versions of this film, and the concise, focused featurette version (narrated by The Tree of Life’s Brad Pitt) is the superior one (the longer version is at least worth it just to hear Knight of Cups’ Cate Blanchett narrating, mind you, but I do find the film a bit more drawn out and passive). With a sublime blend of breathtaking CGI and jawdropping cinematography, Voyage of Time is not just a science lesson: it is a meditative excursion.

7. A Hidden Life

After numerous films that ride off of feelings and ideas more than pure narrative-based storytelling, Malick returned to a more straight forward style (while still being as ethereal as ever) with A Hidden Life: a harrowing rendition of Nazi objector Franz Jägerstätter’s incarceration and torture during the early days of World War II. If the film was solely based on what happened to Jägerstätter, the film would only last an hour. Instead, Malick digs deeply into the farmer’s potential mindset and spiritual dilemma amidst hardship, creating a crushing, three-hour epic that exposes all of the angles present when one’s character and fortitude are being challenged. Meanwhile, we spend time with the rest of the Jägerstätter family, feeling their desperation to have their loved one back at home (Malick’s spacious filmmaking is highly effective here for representing the void in the lives of these aching people). A Hidden Life is a unique cinematic look at anti-fascism that will both soothe and shred your soul.

6. Knight of Cups

I love that Knight of Cups has been reevaluated in the ten years since its release: it’s a damn good motion picture that deserves the adoration. This is Malick’s 8 1/2 (as is the pilgrimage that many auteurs love to take, inspired by Federico Fellini’s masterpiece). We follow a screenwriter’s seemingly aimless escapades while searching for meaning (in his work, and for himself). His journey is likened to a series of tarot cards, with our protagonist representing the titular Knight of Cups, and the people in his life — be they family members or the women he connects with. Malick connects the Major Arcana with religious fables, creating a delirious look at prestige, lust, and self destruction. Boasting some of the finest performances of any Malick film (likely because of the susceptibility necessary for each part), Knight of Cups is as vibrant as it is introspectively lonely. When it comes to the high life and existential dread, Malick plays by the motto represented by the The Magician tarot card: “As above, so below.”

5. The New World

Another Malick film that received many reevaluated takes is his version of the story of Pocahontas and John Smith, known as The New World. The reason why this dazzling historical epic wasn’t properly appreciated upon release was likely because The New World was the first film to boast Malick’s then-new style: one that distances us from the narrative of his films but invites us into the artistry he creates (a fascinating, paradoxical exercise that has never let me down). Now, The New World is rightfully cherished. Not only is it beautifully crafted, it is highly immersive as a historical capsule: a passively told tale of old that allows us to be a part of the discovery. Even if there may be some historical inaccuracies, I’d argue that most period piece films do not feel as welcoming as this, as if we crash landed in the Americas of the sixteen-hundreds and are as aimless as those within the film (the wandering spirits who, too, are looking for purpose).

4. Badlands

Malick’s first film — and one of the great directorial debuts of the New Hollywood movement — is also, oddly enough, the least Malick-like film of his repertoire. An edgy crime film told within South Dakota’s sunset-kissed landscapes (about two misfits who go on a killing spree), even then Malick turns this audacious concept into a work of art (the fire sequence alone is a glorious spectacle). Despite being Malick’s most "conventional” film (whatever the hell that means in this context), Badlands is singular enough to become instantly influential: a dangerous film that doesn’t tire itself on being controversial but, instead, digs into the murkiness of the mindsets of those committing the crimes. There’s even a cameo appearance by Malick himself who — honestly — feels more like a massive, abstract entity than a real person at times (and with films like these, can you blame me for feeling this way); seeing him on the screen is always a treat when I arrive at that scene. In all seriousness, Badlands is a rare thriller that is purely driven by the vibe of what it means to be sinful and unaware of repercussions rather than film’s typical takes on criminality.

3. The Thin Red Line

One of the great war films of all time at this point, The Thin Red Line is as impactful as anti-war cinema gets. We jump right into the shit within Guadalcanal during World War II and are asked to survive through three hours of brutality. The paradox here is the visualization of the atrocities of war against brilliant landscapes; we see how small we are in the grand scheme of things, but also how much destruction we are capable of. Outside of A Hidden Life and Badlands, Malick usually doesn’t dive deeply into punishing cinema, but The Thin Red Line is as intense as he ever gets; it’s also spellbinding to see a typically serene director and his capabilities when it comes to such complicated war-based choreography. When the world was wondering if Malick would ever make a film again after a twenty-year drought, not only did the auteur return, but Malick delivered one of his best feature films to date: an epic that knows how to project as much humanity within the atrocities of warfare as possible. Is it possible to feel any more lost than on the battlefield? The Thin Red Line is the ultimate battle for survival and existence.

2. Days of Heaven

There was a point in time when Days of Heaven was apparently Malick’s last film thanks to decades of inactivity. Even so, that would have been one exemplary high note that the director would go out on. This film features a complicated scheme to strike it rich against the landscape of the settlers within the Texas Panhandle. While deception takes place at the forefront, Days of Heaven is one of the most stunning films in all of cinematic history, creating this undeniable contrast between human indecency and the astonishment of both natural and civilizational progress. The film is already special in this way, but when Malick gets biblical (especially the iconic locust swarm sequence), Days of Heaven becomes untouchable: like a sepia-toned fable. Of course it is great that Malick kept making films since, but it is worth noting how high of a bar he set with only his second feature film (something that feels like an impossible precedent). I also love how contradictorily lush and peaceful Days of Heaven is compared to most other New Hollywood films of this time, proving that viscerality can also come from beauty, not just rage and danger.

1. The Tree of Life

As previously stated, Days of Heaven was a high bar set by Malick with only his second film, and he never topped it with any of his subsequent releases. Well, except for one masterpiece that would follow many years later: The Tree of Life. The first — and best — of Malick’s experimental era (unless you consider The New World to be a part of this wave, but I personally find The Tree of Life even more experimental), there wasn’t any film like this one when it was released. I’d argue — even with some similar titles by Malick since — that there still isn’t a film like The Tree of Life in existence. Not only is this feature uniquely made (the stitching together of memories, dreams, and the unknown), but it is so strong at achieving this vision that it feels like this featured life — a man reliving his conflicted youth in the era of the American Dream — reaches biblical proportions. As we question why we are here (by revisiting the creation of the world, and all of nature and its wildlife, of course), we also see predictions of where we will wind up via one of the wondrous depictions of an afterlife in film. In the middle of it all is a person’s history, and the revisitation of their upbringing and the traumas that came along with it. Above these recollections is narration that doesn’t tell us how to feel but instead questions what we are seeing. Are we what we remember? Can we be more than what has already made us?

The end result is beyond words. I can only attempt to discuss the film and liken it to a holy experience even for the irreligious viewers out there. It is the stretching out of the circle of life, turning a cyclical event into a linear version of life and death (and all that falls in between). The Tree of Life is one of the most ascendant viewing experiences I have ever had with a film. I simply cannot get enough of it, with periodic watches just to relive Malick’s purest vision. My life felt different after watching this opus: as if the mundanity we shrug off and the inner demons we tussle with are just fragments within this miraculous event we are gifted with, and that we must appreciate every day (the journey to this point in our lives is a complicated and brilliant one). I loved The Tree of Life when I first saw it (so did Cannes, who crowned this film with a Palme d’Or). I adore it more and more as time goes by and as I get older. If Malick perfectly captured the rush and richness of life alongside the tragedy of grief and death, I can only hope that his version of heaven is accurate because there’s truly nothing like it (it is one of my favourite sequences in any film). The Tree of Life is as exquisite as film gets, and it is Terrence Malick’s greatest achievement.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.