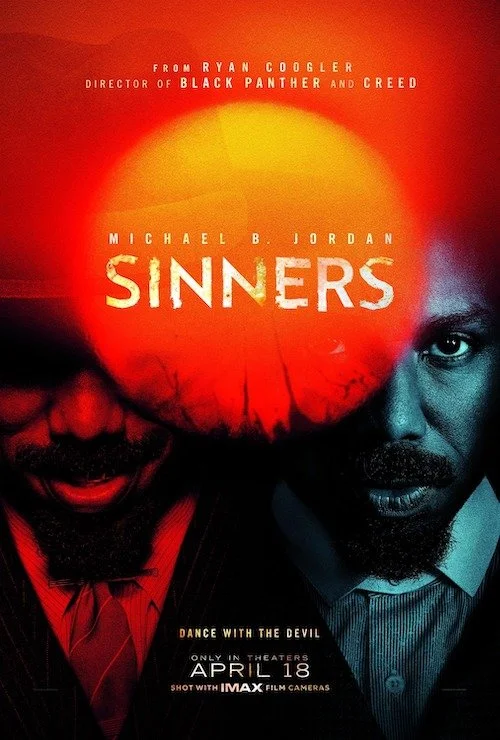

Sinners

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: This review contains minor spoilers for Sinners. Reader discretion is advised.

Although he has never turned in a bad film, Ryan Coogler was a director who I always wished would take on more ambitious projects. Despite releasing one of the best Marvel films with Black Panther (one that actually wears the director’s style on its sleeves, even with the over-involvement of Marvel’s producers being present) and — what I would argue is — the strongest Rocky film ever made with Creed (yes, even better than the original), I wanted to see Coogler come up with original ideas. Ever since his debut, the stunning Fruitvale Station, the Oakland native had such promise that has been untapped for twelve years. All of that changed the day that his latest film, Sinners, released. Of course, I feel like the confidence he accrued while working on — and succeeding with — major properties helped make Sinners work because a sheepish filmmaker wouldn’t dare take on such a project, but I personally feel like he always had the capability within him; besides, if he was daring enough to make Marvel bend to his aesthetics and ideas even occasionally, maybe he could have always made Sinners. Either way, we are at this point now in Coogler’s career, and what a sight it is. We made it.

Music can embody many purposes. One, clearly, is to tell stories, and this opportunity entitles scribes to either candidly describe their own experiences or conjure up a yarn of pure fabrication. Sinners understands both assignments by blending a depiction of the Black experience in thirties Mississippi with a vampire tale. Coogler doesn’t get typical with either story line, even with his abiding by the rules of both natures (for instance, the vampire plot does involve stakes, garlic, and sunlight like most by-the-book vampire tales). Instead, he blends both initiatives into a bayou fever dream: a hallucination of the deep south that swirls dazzling music and beautiful cinematography with a powerful story of generational damnation. Kicking off with a slow burn to allow you to settle into this mesmerizing vision Coogler has waited his entire career to share, Sinners doesn’t reveal all of its cards too early. If anything, it is the patience of the film that allows it to shine as much as it does. Many other horror or action films get too excited and waste all of their energy and best ideas from out the gate. Sinners wants us to lean in closer with our full attention before dazzling us, just like the best blues musicians with their cycling motifs before that guitar wails.

Sinners is a magical realist horror film that cleverly blends its takes on music, Black history, and vampire flicks into one cohesive experience.

Elijah and Elias are twin brothers (both played by Coogler regular Michael B. Jordan) who are wanting to turn a new leaf after surviving World War I and some years working for infamous gangster Al Capone. They accumulate money that they cheated other criminals out of to return to the Mississippi Delta and buy a sawmill with the intention of turning it into a juke joint for the loved ones they previously left behind (as well as the rest of the Black community there). These twins almost embody the two halves of one conflicted man grappling with his demons; Elijah is trying his hardest to find a way out of a life of sin, while Elias feels a little more explosive and too far gone (this duality is tested once Sinners makes its way towards its highly nuanced climactic sequences, enough so that you will begin thinking about what would ultimately be the best choices for our characters in the long run). The film kicks off with a shot of budding blues musician Sammie (newcomer Miles Caton): the son of a preacher who renounces this genre of music as — in his father’s eyes — it is a byproduct of satanism and can lead to supernatural events. As we flashback to the previous night, we meet Sammie again as he comes across our protagonist twins. Coogler including this pivotal scene early on leaves us with the nagging worry as to what happens to Sammie throughout Sinners: a premonition of bloodshed and other tribulations.

We also get acquainted with a myriad of other interesting characters, like the light-skinned — and “passing” — Mary (Hailee Steinfeld) who is a former partner of Elias, and pianist Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo) whose alcoholism is a burden he vows to shake off. There’s this concept that we all carry baggage and that music and dance can be a means of expelling what is weighing us down. For many communities, this includes writing and singing about oppression and finding freedom within the melody and euphoria. A transient, psychedelic sequence roughly halfway through Sinners shows the local Black community within the newly constructed juke joint losing themselves to dance, and the scene coasts through the crowd and begins to bring in different eras of Black music (from an electric guitar solo, to record scratches evoking the birth of hip hop); the dances take part in this as well, and you will find snippets of Black celebration all across history in this spellbinding moment. It’s at this point that the immortality of vampirism hit me; even if we don’t live forever, our artistry and culture will.

This includes having to answer for the problematic history of old, depicted by the inclusion of the Ku Klux Klan as a running subplot. There’s also vampire Remmick (Jack O’Connell) who is an Irish folk singer amassing an army of bloodsuckers. Now, Remmick will attack anyone and his thirst isn’t driven by hate, but the image of a Black community being decimated because of a white person’s idea of longevity and importance is an allegory that is impossible to ignore (and a clear message by Coogler). As Sinners crawls long enough for these many story threads (including those I haven’t even included here), these narratives all collide and never stop acting as each other’s catalyst. The end result is one that feels like a crucible boiling over, and the body count created by vampires biting the necks of the living while mortals kill vampires in self defense just keeps climbing. Even though Sinners possesses the checklist of a slasher film, it never feels senseless or ill conceived. The story all points towards an end goal, even including the ways that characters survive or die (or turn). We are all indicative of both our vices and our virtues. What will we let define us?

Sinners uses its themes of vampirism and musicianship to convey messages of legacy.

You’d think that Sinners builds up towards a massive showdown, and it somewhat does. That’s when Coogler plays his final hand and the true intention of Sinners, and it sneakily borrows from the Marvel playbook as a cheeky mid-credits sequence. Featuring blues legend Buddy Guy as Sammie in the nineties, this final sequence is one that recontextualized all of Sinners for me. Without giving too much away, the film ends on a major hypothetical question: would it be better to be granted with immortality, or for us to leave a legacy that will act as our second life once we are dust? In the wake of the lives lost and those who transformed into vampires, the question bears more weight. We don’t have to answer for our crimes and immoral choices on our deathbeds if we never die. Then again, it isn’t truly living if we cannot pass. How do we make the most of our lives if it never runs out? In a sense, Coogler is reminding us that those with power and hate feel invincible: as if death is never creeping behind them. Perhaps this is why they waste themselves.

To help us appreciate the gift of life through his film, Coogler presents Sinners on 70mm IMAX (his preferred way of viewing the film, should you be fortunate enough to see it this way), with DOP Autumn Durald Arkapaw’s finest cinematography to date. Furthermore, there’s frequent collaborator, composer Ludwig Göransson, trying his hand at a new challenge after winning two Oscars (Black Panther and Oppenheimer). He transports himself to yesteryear with a score that not only elevates the era displayed on the big screen (with thirties-appropriate sounds and melodies, and a heavy use of guitar) but also dabbles in the supernatural mysticism of it all (with revisionist sounds and production). The end result is a new entry of magical-realism used to depict the Black experience that can sit alongside RaMell Ross’ Nickel Boys and Barry Jenkins’ The Underground Railroad. Sinners is as beautiful as it is electric and graphic. It knows that to confront death is to enjoy life; to face history is to cherish culture; to admonish the masses of appropriation and gentrification is to nurture what is being buried. After all of this comes a stake through my own heart: Coogler announcing that he is going to bring back The X-Files. While I am a huge fan of the original series, we just got an exhilarating and exquisite example of how inventive and refreshing Coogler can be with his own ideas. It looks like we will have to wait for that to happen again.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.