Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Charlie Chaplin Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Directors

Sir Charles Chaplin was always an entertainer. When you are effectively known as one of the first — if not the very first — celebrity, you must know how to entertain through and through. After a difficult childhood plagued with poverty and an absent father, “Charlie” Chaplin was merely a teenager when he toured London, hitting up stages to perform and get by. He was not even an adult yet when he was scouted by Keystone Studios, starring in short films. It was only the second and third films where Chaplin’s now-iconic character, The Tramp, debuted; Kid Auto Races at Venice had the character’s first appearance, but the costume that we now know and love showed up in Mabel’s Strange Predicament (both released February, 1914). After a dozen other starring roles, he directed and wrote his first short in April, 1914: Twenty Minutes of Love (also featuring the Tramp). It didn’t take long for Chaplin to become prolific as a filmmaker, releasing dozens of shorts within the span of only a few years; during the earliest days of cinema, film was ephemeral (motion pictures were seen as over and done with once they finished their rounds, and were often thrown out).

After a myriad of short films and studios, Chaplin saw the future when working for First National Pictures and directing The Kid: what was meant to be a couple of short films and wound up being a lengthier feature film. He spotted a lasting effect that film could have with audiences and was turning throwaway flicks into art. This premonition came before The Kid, mind you, as Chaplin helped found the production company United Artists in 1919 with like-minded visionaries like Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and D. W. Griffith. United Artists was meant to provide filmmakers and actors to be financially and artistically independent, allowing films to take off as works to take seriously and not temporary forms of entertainment. To prove this point, Chaplin’s first film with United Artists, A Woman of Paris, was a feature-length drama that he barely appears in (outside of a cameo); this was a passion project meant to show that Chaplin was more than just the Tramp.

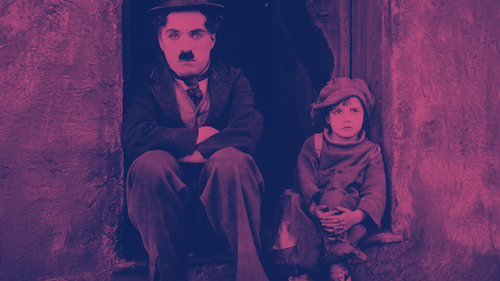

That image is one that will only be hard to shake off if you barely know Chaplin’s filmography. If you have seen even one or two of Chaplin’s films (especially from the United Artists era), you would quickly be aware of what a masterful director and screenwriter Chaplin was. Amongst all cinephiles, this is no secret, and neither was Chaplin’s abundant perfectionism; what looked like slapstick goofiness on screen was hours and hours of writing, rehearsing, and editing done by Chaplin (yes, even editing; in fact, Chaplin had his hand in many aspects of his films; more on the extent shortly). Chaplin kept pushing himself film after film, but his personal life — one that wasn’t so private, seeing as Chaplin was one of the first superstars of the film industry — would prove to be as complicated as he was. This includes the still-controversial marriage to sixteen-year-old Lita Grey (he worked on The Circus during the vicious divorce that quickly ensued), being blacklisted as an alleged communist sympathizer (he would flee to Switzerland in 1952 as a result), and other inescapable events and accusations in the public eye. In between all of this was the shift from silent cinema to talking pictures; seeing as Chaplin was particular with his style and what he could accomplish, he would be one of the last silent-film bastions to hang on to the ways of old, making silent classics even in the thirties.

The latter stages of his life and career were spent with Chaplin re-editing and scoring (composing new scores for, essentially) his classic films; helping usher them into a new, refined age of Hollywood (one where legacy mattered for good). By 1972, not only was Chaplin welcomed back to America, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded the director with an honourary Oscar which resulted in a reported twelve-minute standing ovation: the longest of any Academy Award ceremony. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1975. He passed away on Christmas Day in 1977. Considering how early he started his career and that his final film was only ten years before he died at the age of eighty-eight, not only did Chaplin work in the film industry for many decades, he dedicated a majority of his life to this craft. With his massive legacy came a family of entertainers, including daughter and actress Geraldine Chaplin (and, subsequently, her daughter and Charlie’s granddaughter, Oona Chaplin, named after Charlie’s last wife and Geraldine’s mother, Oona O’Neil). Chaplin’s impact is still felt over a century later, either through his influence and mastery or his descendants who have met the different eras of the film industry; Oona Chaplin staring in James Cameron’s Avatar: Fire and Ash shows just how different cinema is from when her grandfather was carving a place for auteurs and dedicated performers.

While it would be nice to go through all of Chaplin’s short films, I think it can get a little silly to rank around forty short films that are essentially neck-and-neck in quality, so — despite the clear sacrilege — I will be focusing just on Chaplin’s feature films (of which there aren’t nearly as many). I think that there is enough to work with here, and that a bulk of Chaplin’s greatest triumphs stem from these feature films. Now, I always go by the Academy’s regulations as to what constitutes as a short film, and that is any motion picture that is less than forty minutes long. Despite being considered a short film, The Pilgrim is forty-six minutes long, so I will be including that — something I’d consider more of a featurette, really — on this list. Chaplin did have a couple of duds, mainly towards the end of his career. Otherwise, the majority of the films below are sensational and are clear evidence that Chaplin is one of the finest filmmakers of all time. For any newcomers to the works of Chaplin, I hope this list can dispel some stigmas, including that he was a comedian first and foremost, that he only made great silent films (although the recent obsession with The Great Dictator has put that concept to bed, thankfully), and that he was his main character; to me, there is the Tramp, and then there is Sir Charlie Chaplin. One makes me laugh in many different ways, and the other has taken my breath away as a pivotal voice in the medium. Here are the films of Charlie Chaplin ranked from worst to best.

12. A Countess from Hong Kong

Chaplin’s last film, A Countess from Hong Kong, is also easily his worst. You can argue that it is hokey, unfunny, and formulaic, but its biggest offense as a Chaplin film is that A Countess from Hong Kong is flat-out unmemorable (something Chaplin never was before). The film comes off as a run-of-the-mill romantic comedy of its time without anything that stands out in particular (outside of a recycled gag where Natascha — played by the always lovely Sophia Loren — goes into hiding every single time someone knocks on the door; this does stick out, albeit because it happens a dozen times and lands zero laughs). I’m not sure if this film was meant as a means for Chaplin to ease back into filmmaking, but A Countess from Hong Kong is as plain, below-par, and uninspired as a Chaplin film ever got; his filmography sadly goes out with a whimper.

11. A King in New York

We leap quite a bit in quality with this penultimate film: one that I’d call decent. A King in New York is the last Chaplin film to star himself, and it only makes sense considering the fact that he plays a fleeing monarch who becomes an icon over in New York and is flagged as a communist (outside of the character heading to the United States and not away from it, this is quite autobiographical). Chaplin crafts a rather scathing and cynical film that comes off as bitter enough to be at least a little bothersome. If you are a major fan of his works as a director or actor, then I don’t see what massive harm would come out of watching A King in New York, but I do think that there are numerous better places to start when exploring Chaplin’s filmography than what feels like a bit of a mean-spirited letter to Hollywood.

10. The Pilgrim

Not quite a short but not quite a feature film, The Pilgrim and its forty-six-minute run time feels necessary to include here. I did explain that I operate by the Academy’s rules on what constitutes as a short film (anything less than forty minutes long), but I also view The Pilgrim as a bit more than just your average Chaplin comedy. The Kid feels like Chaplin’s initial push for something more, but The Pilgrim — to me — acts as the bridge between Chaplin’s comedic-shorts era and his prime as an established director. This comedy about a fugitive who winds up becoming a small town’s priest saw Chaplin getting up to his usual slapstick shenanigans while also expanding a comedic story into something more substantial as he toyed with this narrative as more of a long form vehicle. This is another film I’d recommend to diehard Chaplin nuts, but The Pilgrim is still a solid and fun affair.

9. A Woman of Paris

Chaplin’s first directed film in his celebrated United Artists era, A Woman of Paris feels like a major turn for the silent-era superstar; if anything, Chaplin is barely in the film at all. A Woman of Paris belongs to Edna Purviance who starred in many of Chaplin’s films (from a myriad of shorts, all the way to uncredited cameos in Monsieur Verdoux and Limelight). Her stellar performance serves her character, Marie St. Clair, and her dilemma as she feels stuck between different sides of who she wants to be (she cannot have it all). Here, Chaplin is telling a story of existential murkiness and he goes the extra mile with prestigious filmmaking, narrative depth, and an end result that tugs at you. A Woman of Paris is a great deviation from a director who had it all figured out and, in ways, it felt like a sign of what cinema could be (especially when auteurs were to go against type).

8. The Circus

What happens when a clown — who happens to be the Tramp, of course — can only entertain and be funny by accident, and not when intended? That is Chaplin’s The Circus: a clear statement on the demand that comes with being an entertainer (and how difficult it can be to amuse others). Then again, this could just be a typical Tramp comedy, but it’s a damn good one at that: one that is full of silly stunts, kinetic antics, and everything one could ask for from a Chaplin romp. Its bittersweet ending is one that saw the future and what Chaplin could be capable of: a hint of emotion and beauty within a film of frequent hilarity (City Lights was just around the corner). When we entertain, we change an audience’s day; they get up and leave to proceed with the rest of their lives. What remains for entertainers when the house is now empty and the lights are off?

7. Monsieur Verdoux

If Chaplin had an underrated film, it would have to be the dangerously funny Monsieur Verdoux: a film that is so bleak that it almost doesn’t seem like it could be a Chaplin project. To get by after being laid off from his career as a bank teller, Henri Verdoux (Chaplin) marries and murders rich women; keep in mind, Henri is properly married to a disabled wife, whom he has a child together with. As Henri finds himself in trouble, Chaplin uses the opportunity to remind us that others, including politicians, have committed far worse crimes than what Henri here has (a bold stance if I’ve ever seen one). This is also an attack on the Hollywood Code during the Golden Age if I’ve ever seen one: if Henri gets his comeuppance, what about everyone else who doesn’t? Is this truly a morally correct ending if we are now aware of what doesn’t get fixed? Is it bad that we find Henri amusing despite all of his sins? Chaplin never came close to being a part of the New Hollywood movement, but this magnificent satire leads me to believe that he could have released a great film within it if granted the opportunity.

6. The Gold Rush

Consider every film from this point on an absolute masterpiece of cinema. The Gold Rush is exactly how it reads on paper: a classic Chaplin short that is properly elongated to a feature length. What this means is that you get a bit of everything, from proper laughs and charm to enough narrative length for the Tramp to experience a touching and engaging arc. The Tramp hopes to strike gold during the 1890s rush and his pursuits may make for great entertainment but it is the purpose of his efforts that make The Gold Rush so enticing. Sure, it may be fun to see the Tramp stumble about, but here we may get a chance to see him succeed. With Chaplin’s expansion towards major feature films, he was now crafting landscapes and realities that you could feel immersed in, feeling every ounce of that frigid snow as the Tramp traversed through it. In ways, I also find The Gold Rush to be Chaplin’s richest film artistically, with some magnificent shots of the Klondike region and the cabin at the epicentre of the film (it almost feels like its own character, doesn’t it?); there is a visual whimsy here mixed with precise detail that feels like a precursor to the style of directors like Wes Anderson decades before they would even exist.

5. The Kid

What is worse than being dirt poor? Being a child who is dirt poor. The Tramp meets an orphaned child in The Kid and they both face the hardship of living impoverished lives together (but at least they have each other). Things get complicated when the child’s mother winds up returning and being able to now provide for him; should he leave the Tramp for a more lavish and fortunate life even though the Tramp was far more of a parent than his birth mother ever was? Chaplin accomplishes a lot in a crisp hour of phenomenal, silent-era cinema; while short by today’s standards, The Kid was a longer film for Chaplin at the time and he put everything into a then-lengthy production to make this film work (his efforts ooze in every single frame). Take it from Chaplin, who was once known more for being a character (the Tramp, obviously): cinema was meant to have characters you deeply cared about. During a time where film was at least still a little disposable, Chaplin created two characters who would never leave you.

4. Modern Times

Perhaps a retort to the forever-shifting film industry that had abandoned many silent icons in favour of fresh faces in the talkies era, Chaplin’s first part-talkie (but mainly a silent motion picture, really) was Modern Times: a jab at the constant rush of innovation and the many everyday people who get left behind. The Tramp tries to keep up with the hustle and bustle of society, starting off by working an assembly line before having to pivot many times to both keep afloat and also aid his romantic partner, Ellen (played by Paulette Goddard). The need to hop from story to story allows Modern Times to sneakily be a set of vignettes (a best-of compilation of the Tramp’s comedy shorts, if you will). Noting the tug-of-war between Modern Times remaining a silent film versus the Tramp (and Chaplin) flirting with sound is quite a treat (ultimately, this would wind up being Chaplin’s final silent picture in any capacity); if we could learn something from this film on that note, it’s that we lose the heart of the old way when we push to evolve too quickly (films may have been changing, but Chaplin knew that his old formula would remain forever).

3. Limelight

Chaplin’s last film for United Artists — and the last of his prime years, which lasted for decades — is the crushing comedy-drama, Limelight: a surrender to Father Time. Chaplin is Calvero: a former clown who now suffers from alcoholism and becoming cursedly irrelevant within his field. Then there is Terry, played by Claire Bloom, who is a suicidal ballerina who has her whole life ahead of her; Calvero tries to help her see that. Limelight shows Chaplin doing what he does best with the same amount of charisma and electricity that he exuded when he was a whippersnapper years before, but this film also carries a major sense of self-aware tragedy with it. When you are a celebrity, that curtain will come down at some point, whether it is through death or an audience who has moved on from you. For Calvero, both possibilities loom over him, and the titular limelight becomes the spotlight: all wait in anticipation for Calvero to fail; to flounder; to die. While other filmmakers can get carried away with thinking that they still have talent, Chaplin was staring at his own oblivion while making Limelight and he was all but ready to accept that his time had come; if anything, he proved that he was just as gifted as he’d ever been. Limelight is slowly being realized as one of Chaplin’s greatest triumphs, and even then I feel like it is being undersold. This is a must-see film, and a work of brilliance.

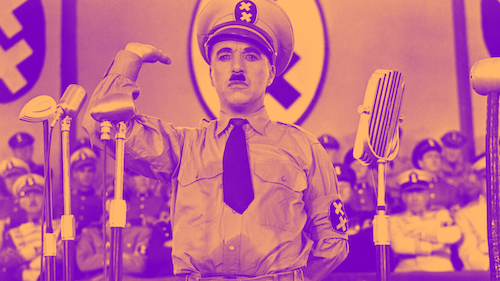

2. The Great Dictator

Over ten years into the talking pictures era, the world was begging for the Tramp to speak. He finally does in The Great Dictator: the film that retired the character for good (where else could Chaplin go after this?). Chaplin uses this major change from his typical style to scold the rise of Adolph Hitler, with the Tramp — who sadly shares the same square mustache with the fascist tyrant — being confused for the film’s central dictator (Adenoid Hynkel). Chaplin plays both to perfection, adding the pure dangerous delusion necessary for the world to worry about Adenoid while showing the confidence needed from an everyday struggler to alert the masses about what is really going on behind the scenes. For Chaplin to create this satire is a massive risk in and of itself, but Chaplin goes the extra mile; if the Tramp is now to speak, he will say everything that he must. The end result is one of the greatest monologues in film history: a call to action to protect everyone and for all of the masses to unite against corruption. In recent years, The Great Dictator has grown as one of Chaplin’s crowning achievements and it is easy to see why; the state of the world is still awful (and history sadly appears to be repeating itself), and Chaplin’s clever political comedy has left many inspired films in its wake.

1. City Lights

Talking pictures were finally figured out. Recording techniques were improving to the point of sound films making proper sense (as opposed to the handful of films that got rushed out to be one of the preliminary sound staples). Then there was Chaplin: someone who absolutely refused to play ball when he still had a silent film left to tell. That last solely-silent picture is City Lights: a film so iconic that it stands well above being simply labeled a film without sound. The Tramp has returned, but he’s never been better than he is here. As poor as he’s ever been, the Tramp comes across a bit of money; he wishes to use these means instead to help bring sight to a blind flower girl, played by Virginia Cherrill. The Tramp tries to earn more money to help this miraculous procedure take place and never cares to help himself with even a single dime. However, what will happen when the flower girl gains sight? Will she see the Tramp and no longer care about his existence (like almost everyone else around him), or will she still see the real him? What transpires is one of the great film endings, which boasts a pair of breathtaking performances that is sure to bring tears to your eyes; yes, Chaplin has allowed all of us to see.

City Lights is as funny as any Tramp film ever got, but with each vignette being a part of a bigger, cohesive picture. What elevates this motion picture even more is how Chaplin perfected the romantic film with a vision that surpassed expectation back then and set a precedent for the rest of time. At this point, Chaplin knew how to make a feature length film that easily carried the energy of his short films but possessed multitudes of emotions and purposes in a fully-fleshed story. Of course, we are aware of Chaplin’s talents now, but had there been any naysayers back during the early days of cinema — those who viewed Chaplin’s comedy as entertainment but not as art — they were likely shushed by the magnificence and exquisiteness of a film that is still as amusing and hilarious as City Lights. That already would have been an achievement, but the fact that City Lights is as gorgeous and emotional as it is is a revelation. City Lights is one of the great silent films (and one that stood in defiance in an industry that abandoned the old days as quickly as possible). It is a masterpiece of the comedy and romance genres. It is Charlie Chaplin’s greatest motion picture of any length so, as a result, it remains one of the best films ever made; it is an unforgettable rush akin to the butterflies in your stomach when you fall in love, the crushing weight of regret when life turns sour, and the cathartic release of anguish when your day — or life — has been made and rectified.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.