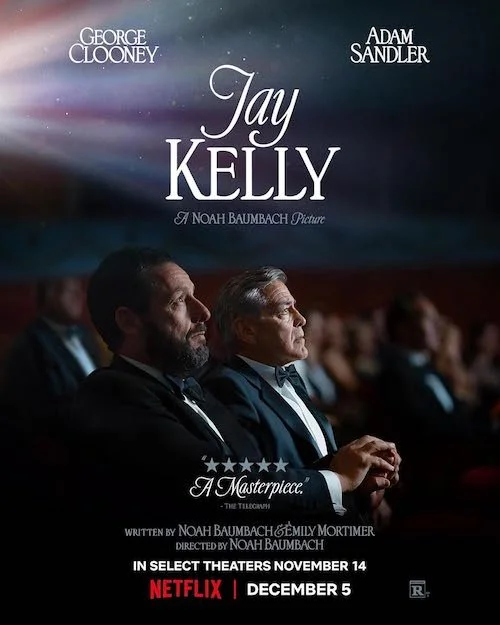

Jay Kelly

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: This review contains minor spoilers for Jay Kelly. Reader discretion is advised.

Imposter syndrome affects us all. Yes, even filmmakers and movie stars. Noah Baumbach is no stranger to putting his soul on the line with highly forthright pictures like The Squid and the Whale, Marriage Story, and Frances Ha: all stories that comment at least partially on Baumbach’s personal life as a New Yorker, the son within a broken family, and an individual who questions their purpose in life. The next best New York writer-director with a hint of jazz flow within his dramedy ways since Woody Allen, Baumbach — like Allen — also has his fair share of misses which stem from honest efforts to try something new; not many would dare take on the responsibility of adapting Don DeLillo’s postmodern classic, White Noise, and Baumbach’s mediocre attempt is far more successful than what would have transpired in the hands of most others. Perhaps because he is still on the train of ambition since White Noise, Baumbach has returned with a highly meta comedy-drama that blurs many lines; the past and the present; a film set and the big screen; what was produced for the film and what the audience receives. That film is Jay Kelly, and — all things considered — it might be the most Baumbach has put on the line in his whole career.

The majority of promotional materials for Jay Kelly sell the film as a quirky, sentimental look at a veteran actor’s midlife crisis during his twilight years, but I was pleased to find that the motion picture is a little more intricate and interesting than it is being sold. Sure, there is the title character, Jay Kelly (George Clooney, who may be at his most Cary Grant than he’s ever been here), and he may be facing an existential crisis. Jay is set to partake in a new project, but he begins to threaten retirement by embarking on an impromptu trip to Paris. This clearly startles Jay’s manager, Ron (Adam Sandler), and publicist, Liz (Laura Dern), who abandon all of their professional and personal responsibilities to join their client on this European excursion. What trailers may not tell you is that this trip is driven by Jay’s inner demons; his regret for not helping out a filmmaker (Jim Broadbent) who was responsible for Jay’s breakthrough and was asking for a financial favour; his tainted past with former best friend and fellow actor, Timothy (Billy Crudup), who Jay may have stolen a promising part from; his concern that he has lost time with his family, particularly daughters Daisy (Grace Edwards) and Jessica (Riley Keough).

Much of Jay Kelly is told with a certain sense of fluidity. The opening shot is a complicated single take on a film set with Jay trying to nail his final scene; he keeps finding excuses to retake this scene as to not wrap up the production and, as a result, stop doing what he loves. A majority of the film takes place on a train that departs from Paris. Jay Kelly also merges the title actor’s memories with the present, as if he is literally revisiting moments of his life like a director watching production footage after a long day of shooting. With this in mind, the film is clearly conscious of the curse of time; how quickly it flows, how easy it is to lose track, and how effortlessly our guilt keeps up with us despite the speed of existence. In that same breath, Jay Kelly is also about legacy. The same film that has an effort to conduct damage control regarding a fight that Jay was a part of also has Jay taking down a bag thief. Jay has the opportunity to release a new film, influence headlines, and other methods of reclaiming his innocence. This felon is now marred by his disparate decision to steal an old woman’s purse. Jay is instantly recognized as a hero, and the thief, well, a thief. Jay notes what is happening and tries to defuse the situation, knowing how damning a legacy can be (yes, even when you are an icon). If anything, Jay may see himself in the robber: someone who saw an opportunity to try and fix his life at the detriment of someone helpless and innocent, and swooped in.

Jay Kelly is an ambitious look at aging and regret in the form of a love letter to cinema.

Even so, Jay Kelly proves to be even more nuanced than that. Ron’s life gets heavily swayed by Jay’s decisions and other forces. Unlike Jay, Ron doesn’t have the many safety nets that a pop culture superstar does, so consequences prove to be much more dire to Ron. In a pivotal scene of the film, one full of inevitable confrontation, Ron reminds Jay that “You’re Jay Kelly” and “I’m Jay Kelly”: an indication that Ron put in the massive amounts of legwork to get Jay work. Jay retorts that Ron is nothing more than a friend who gets fifteen percent of my earnings. The savage response was partially dictated by the use of alcohol, but Jay’s projecting; his anger for Ron is actually anger at himself. it stems from the feeling that he stole his life of fortune from a friend, and that he has rid himself a normal life with authentic connections. He then blames Ron because he cannot fully blame himself (least of all when his mug is on a fifty-foot banner right beside him at a party dedicated to his honour and image, one he knows is a fabrication aided by people like Ron). At a tribute event for Jay, both the actor and his manager attend — not as partners, but as friends (and, certainly, the two sides of the same coin).

Baumbach is doing more than merely lamenting Jay Kelly’s inner turmoil. He is acknowledging that cinema is in a tough spot, but it is more important than ever. This is certified by Jay’s tribute, one that is compiled of performances throughout the actor’s career. However, Jay Kelly cleverly uses clips from George Clooney’s filmography, and fairly obvious cuts are selected as well (Clooney’s Oscar-winning turn in Syriana, Leatherheads, From Dusk Till Dawn, and other recognizable films that cannot be mistaken for anything else). If it hasn’t dawned on you already, it should now: Clooney isn’t getting any younger. In the film, Jay Kelly is celebrated as one of the last traditional movie stars of yesteryear. That’s Clooney: a person of a different time. The film ways of old are endangered; even if film continues (and, despite the red flags, I believe film will somehow persevere in some capacity for a long time), the cinema that once was is long gone. Silver screen legends are replaced with online personalities. Lengthy theatrical spectacles are no more, as films are instantly banished to streaming (the irony that this is a Netflix title that has had a very limited theatrical run isn’t lost on me). Films aren’t the event that they once were. They will always matter to me; to cinephiles; to Noah Baumbach.

Due to this recent acknowledgment that cinema as an industry is in a strange place, numerous filmmakers have crafted their homages to this medium; Sam Mendes missed the mark with the lush-but-dull Empire of Light; Steven Spielberg delivered a much stronger job with a confession of how film saved his complicated youth with The Fabelmans; David Fincher’s Mank details the magic of film whilst accepting the hideousness of the industry’s innerworkings; the list keeps growing. Baumbach’s answer to this trend of self-reflection is Jay Kelly: a study on imposter syndrome. An early quote in the film mentions how film acts as an encapsulation of moments and memories in time for those in the film industry. Baumbach knows that better than many. He has depicted the divorce of his parents multiple times in his films. He has put himself and his insecurities on the big screen time and time again. With Jay Kelly, he expresses his fears that at some point this train — film, the spark that keeps us going, life itself — will come to an end. For some, it already has. Baumbach dares to hang on, but he knows that he can only do so much; Jay Kelly is a touching attempt to at least state the obvious but with the director’s signature surrender (it is his vulnerability and admittance of his own flaws that helps propel Jay Kelly).

In ways, this film feels like Baumbach’s answer to a Federico Fellini film (the eventual Italian connection in the film is not why). Baumbach shows the high life of celebrity while also grappling with the self-loathing and loneliness that comes with an iconic status. Baumbach delivers this incredibly audacious film to spill his soul. I often hear that Baumbach whines about his life of privilege; that the divorcing couple in Marriage Story have massive properties and wealth to split (oh woe is them), for instance. I understand the potential for accidental gloating, but should a director be condemned for writing about what they know? Jay Kelly does boast a lavish lifestyle underneath the depression and anxiety, but I don’t think that means that it is detached from the everyday viewer. Yes, you can view Jay Kelly as a film about an actor at the end of the road. Or, you can view Jay Kelly as a film about a person who wants another shot at a life they took for granted; at the choices they mishandled. The film ends with Jay Kelly’s tribute, where the audience is treated to a montage of his career while he is blessed with a memory of happier times with his family. Jay — and George Clooney, really — looks at the camera (and us in our eyes) and asks us to do another take (a callback to the start of the film). Life doesn’t grant second takes. How is this a lavish life if it is full of regrets? Film has the power to heal, particularly the audiences who get moved by what they see. When you’re a Jay Kelly, or potentially a Noah Baumbach, who continuously try to cure themselves with their passion, maybe there is no end or resolution; at least there may be for those their work reaches. Film cannot die. Baumbach doesn’t want to die. With another cinematic time capsule like Jay Kelly amongst the countless others (in history, and in Baumbach’s filmography), maybe neither have to.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.