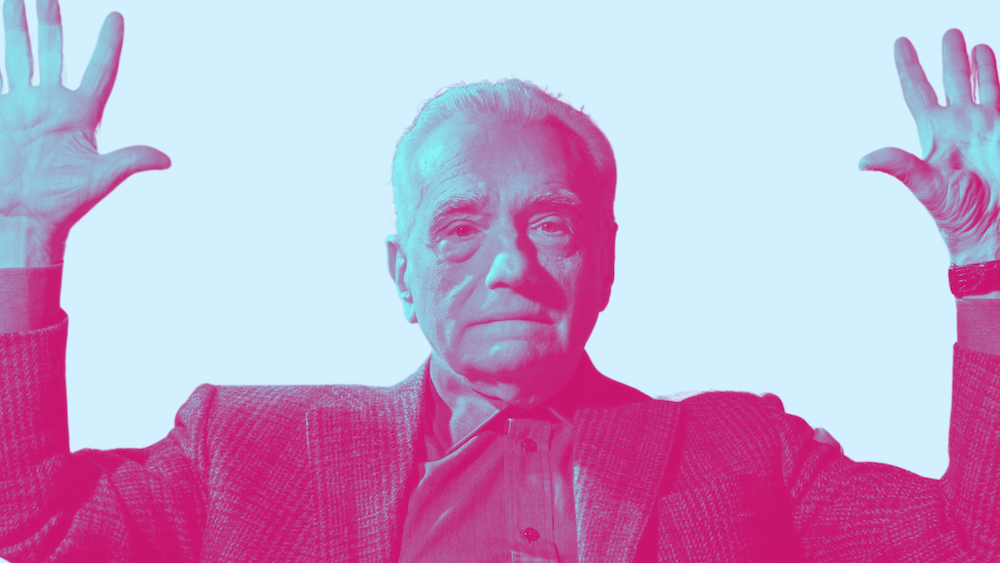

Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Martin Scorsese Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Directors

What can be said about Martin Scorsese that hasn’t already been brought up? Undeniably one of the greatest directors of all time, Scorsese rose when Hollywood was being spun on its head. While the wave of New Hollywood visionaries sought to bring authenticity and break the rules beset before them (and Scorsese was a part of this troupe), he had an appreciation of the ways of old that were hinted at throughout each and every picture. There was something more traditional and orthodox around the corner for every scene of violence. As a result, Marty’s filmography has both challenged and embraced audiences over fifty years. We are pushed to examine what Hollywood cinema can be while reminiscing on what it once was. With these notions in mind, it’s safe to say that almost no one understands the fundamentals of American cinema as well as Martin Scorsese (at least in this day and age).

His expertise goes beyond what he crafts. He has aligned himself with some of the cinematic medium’s greatest minds, from thespians (Robert De Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio, Joe Pesci) and cinematographers (Michael Ballhaus, Michael Chapman, Roger Deakins) to writers (Paul Schrader, Terence Winter, Steven Zaillian) and the greatest editor of all time (who has worked on every film of his since Raging Bull) Thelma Schoonmaker; he actually met Schoonmaker while the two of them worked on Woodstock as co-editors amongst others. Scorsese has also done a lot to preserve film history, including founding three different nonprofits (The Film Foundation, the World Cinema Foundation, and the African Film Heritage Project); a myriad of crucial works of yesteryear were resurrected particularly by the World Cinema Project, including The Color of Pomegranates, La noire de…, Los Olvidados, and Touki Bouki.

It’s cheap to insist that Scorsese is the master of crime and gangster films when he has made and done so much more for cinema. If I should bring up some prevalent themes in his career, he definitely focuses on the rises and falls of individuals who punish themselves, existentialism and nihilism, love letters and heeds of caution for New York City (straight from the heart), and both karma and retribution (usually from a Roman Catholic perspective). He also wears his influences on his sleeves (whenever it is appropriate to do so, of course), be these specific shots, devices (like soundtrack dissonance from Scorpio Rising throughout his career, or specifically the fourth wall breaking via a firing pistol to close off a film à la The Great Train Robbery as seen in Goodfellas), or his favourite songs. Scorsese has a particular affinity for The Rolling Stones, whose songs can be found in enough of his works (he also directed the documentary Shine a Light). With that in mind, let’s put together a playlist of some of my own personal favourite Rolling Stones songs, which may put you into the headspace of this list (in no particular order):

• ”Sway” (Sticky Fingers)

• ”Let It Loose” (Exile on Main Street)

• “Tops” (Tattoo You)

• “Under My Thumb” (Aftermath)

• “Lies” (Some Girls)

• “Gimme Shelter” (Let It Bleed)

• “Sweet Virginia” (Exile on Main Street)

• “Moonlight Mile” (Sticky Fingers)

• “Paint It, Black” (Aftermath)

• “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” (Let It Bleed)

• “Doo Doo Doo Doo (Heartbreaker)” (Goats Head Soup)

• “Salt of the Earth” (Beggar’s Banquet)

• “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” (Sticky Fingers)

• “Little T&A” (Tattoo You)

• “I Just Want To See His Face” (Exile on Main Street) (no one else on Earth will say this is one of their favourite Stones songs, so here I am. This song is amazing)

Now that we’re ready to dive into the feature films of Martin Scorsese, I want to preface that there will be no documentaries on this list (that is something I wish to tackle in the future), nor will there be anything that doesn’t constitute as a feature film (so no shorts, music videos, or television episodes). I’d love to celebrate all things Marty as he is in my top ten favourite directors ever, but then we’d be here all day. This is just a look at his feature films. Also don’t get too bothered by the rankings on this list: outside of two films (which we’ll get to shortly), I like-to-adore every single feature Scorsese has ever released. Let’s not beat around the bush anymore. Here are the feature films of Martin Scorsese ranked from worst to best.

26. Boxcar Bertha

The only film I would call bad in all of Marty’s filmography is his second feature Boxcar Bertha: a series of interesting, unorthodox ideas that would blossom into his signature traits down the road that amount to very little here. In this New Hollywood experiment, we see Barbara Hershey (one of my favourite actors) and David Carradine starring as Boxcar Bertha and Big Bill Shelly (respectively) taking part in crime with The Great Depression as their backdrop. The film feels as unruly as these fugitives, and it is neat at first; the charm wears thin quite quickly. This one is only for Scorsese obsessives; they’re the only audience to find merit in a film where a rising filmmaker tossed everything at the wall to see what would stick (he would quickly figure this out, fortunately).

25. New York, New York

Marty has operated with longer films on an occasional basis, but New York, New York is the only film of his that actually feels long. It’s interesting to see Robert De Niro and Liza Minnelli share the screen and bounce off of each other, but the former is handed the weakest character he’s ever had in a Scorsese film (De Niro’s Jimmy Doyle is a bit irritating), thus making the potential for exciting chemistry feel squandered. I do like how Scorsese zeroes in on the ennui between both tired souls within the titular city that is usually associated with dreams and reinvention as if to say that the grass usually isn’t actually greener on the other side. I’m glad I’ve seen New York, New York once for its potential and the little it does pull off (mainly in its stance on disillusionment), but it’s sadly one of the very few Scorsese films I don’t wish to ever revisit.

24. Who’s That Knocking at My Door

Now we get into the good stuff from here on out. We’ll start off with imperfect films I still have more positive things than negative things to say. Here’s Scorsese’s debut, Who’s That Knocking at My Door: an exciting indie feature that helped put both Marty and mainstay Harvey Keitel on the New Hollywood map. Unvarnished yet confident, this first film is quite strong for most of its ninety-minute duration. My major complaint is that I wish there was more, but it’s understandably brief because of Scorsese’s then-unknown status and the scant budget. Even if not every idea works, enough of them here do, and it’s easy to see why Scorsese was supported from the get-go. While I would still recommend this film for Marty fans first and foremost, anyone with a passion for independent and New Hollywood releases will find something of value in the small-but-mighty Who’s That Knocking at My Door.

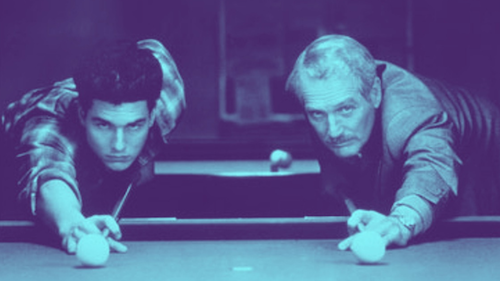

23. The Color of Money

I was a huge supporter of this sequel to The Hustler, particularly because it seemed like a unique hypothesis on what a cinematic sequel can be (this still feels very much like Scorsese’s answer to the aforementioned film as opposed to a direct, thematic sequel). When I first caught The Color of Money, I was prepared to declare this a criminally underrated film. I love the style, the assuredness, and the tension throughout this feature. Yes. I was a huge supporter of The Color of Money until I got to its ending: the worst in Scorsese’s filmography. It’s one that clips the rest of the film at its knees and encourages its fall. Even though I can’t get behind the openness of how this film concludes (which feels more like a shrug than a resolution), I do think The Color of Money is worth checking out at least once. It’s sleek, quite exciting, and it houses Paul Newman’s sole Oscar-winning performance (Tom Cruise is quite intriguing in this film as well).

22. Gangs of New York

I loved Gangs of New York as a tween when it first came out, especially because it introduced me to my favourite actor (Daniel Day-Lewis, who is unstoppable as Bill the Butcher here). The more I understood about film as the years rolled by, the less I liked this film. It’s a rare moment where it feels like a studio interfered with what Marty was trying to pull off, and even the director himself would go on record to profess his frustrations while working on this film. There is still much to admire here from the breathtaking costumes and sets to, well, Daniel Day-Lewis: he alone makes the entire three-hour runtime feel feasible. Otherwise, some ideas and storylines feel stymied in this otherwise-ambitious epic. While the out-there casting of Cameron Diaz didn’t quite work out here, the similarly peculiar casting of Leonardo DiCaprio would result in a major partnership between the actor and director, and they would only go on to do better things together from this point on.

21. Cape Fear

I love this film, but I can acknowledge that it is a little off the rails. Scorsese’s remake of J. Lee Thompson’s film of the same name feels like a then-contemporary love letter that both honoured a classic while trying to reinvent it for a new age. The end result is an unhinged, hyperbolic psychological horror that intentionally pushes itself to the extreme to the point of taking you out of the experience. What I love about this is that, even with all of this melodrama, Marty still doesn’t feel like an auteur who is trying too hard: every decision has worth and purpose. There are enough nods to the original (including the cameos of Robert Mitchum, Gregory Peck, and Martin Balsam) to remind you of the honest place Marty was working from; it’s as if he made this film when he did to try and encourage a shakeup in a Hollywood that felt like it was getting sappy again via source material known for its taboo nature. Cape Fear is nuts, and I kinda like that it is.

20. Shutter Island

I appreciate Shutter Island more as a time machine and as a tribute to the styles of yesteryear than I do a standalone film. I find the major twist here far too predictable, but I do think the film functions decently on subsequent viewings as a vessel for a broken man with an even more fragmented mind. I like that the film is garnering more appreciation over time because of what it does quite well (the modernization of Golden Age psychological thrillers), but I cannot get on board with the notion that this is up there with Scorsese’s best works, or that it can rival the other 2010 DiCaprio film Inception (excuse me, what?). What I will say is that Shutter Island by anyone else’s standards is a solid, interesting film that would have made a bigger splash in their filmographies. For Scorsese, this is just a taste of how great he can be. Still, I’ll always encourage Marty to try new things when they come from a place of knowledge and intrigue to venture forth through new cinematic corridors. I do like Shutter Island, but not as much as others do.

19. Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore

After his big breakthrough Mean Streets, Scorsese was already looking to deviate from the crime genre he was cornering himself into. His fourth film, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, is a celebration of everyday Americans who have to fight uphill battles every day of their working-class lives. Alice Hyatt (played in an Academy Award-winning performance by Ellen Burstyn) sports the frustrations of mundane livelihoods on her sleeves, and you root for her and her son to get by throughout this dramedy. This one goes out to those who proclaim Scorsese only works within the confinements of violence and controversy and is incapable of making strong female characters: he did so at least once with this celebration of the underdog finding her footing.

18. Hugo

The sole family film Scorsese ever made couldn’t just be an all-ages affair, could it? As often as Scorsese has shown his adoration for cinema, he never proved it quite as strongly as in his Love Letter Hugo: a tribute to the ways of filmic old disguised as a children’s film. A celebration of the groundbreaking works of Georges Méliès, Hugo is educational for the curious and heartwarming for those craving the nurture. The dichotomy between classics and the modern age is solidified via the use of 3D: Hugo remains one of the best 3D films I’ve ever seen in a theatre, especially because it is a device that shows the distance that film has gone. I’d like to see Scorsese within this environment again, because he clearly handles all ages affairs well: Hugo always treats both children and adults with seriousness and understanding.

17. Bringing Out the Dead

If Scorsese ever channelled his New York City cohort Spike Lee, the end result would be Bringing Out the Dead: a film that feels more in line with Clockers or 25th Hour than it does some of Marty’s other films. As we traverse the streets of New York, New York in the wee hours of the morning, we spot the desperation of citizens in an environment that encourages them to fester rather than grow. The delirium envelops you as you watch, and Scorsese truly evokes the sensation that we’re up way past our bedtime to the point of vulnerability and dread. How do paramedics save the lives of others when they are in their own downward spiral? Such is the question in Bringing Out the Dead: a reminder that those who help others could use a bit of love and support themselves. Here, they are seen.

16. Casino

Casino gets unfairly tethered to Goodfellas because of their slight similarities, but the former feels more like an artistic look at grandiose corruption while the latter is more precise and sharp with its style. Casino feels like Marty is treading in similar territory as before, but I also feel like this film goes to places he hadn’t before or since when it comes to the inherent nature of self-corrosion; sure, he’s documented the rises and falls of his protagonists, but in Casino Marty’s protagonists feel like they are boiling alive in a proverbial hell for us to see. Sure, Scorsese has tackled this sort of thing in better ways, but Casino stands alone with its maturity and quest to be absolved from those who are aware that they are heading towards their demise (not when they have reached their low already) and can do nothing to stop the inevitable.

15. Silence

The weakest of the three religious epics in Scorsese’s repertoire is still a fantastic exposition of faith and righteousness. Silence is arguably Scorsese’s most arthouse release, and the director’s passion is all throughout this narrative about two dangerous quests (one to rediscover God, and another to find a fellow Jesuit priest in Tokugawa era Japan). This was a project stuck in developmental hell for twenty-five years, so its eventual release in 2016 felt like a miracle for Marty. The end result is a harrowing yet sublime journey of self and the world where God works in mysterious ways. Those who are quick to label Scorsese as a master of violence and swearing don’t reflect on how spiritual the auteur is, which is a theme that he seems to include at least a little more frequently in his works (don’t believe me? Compare how many of his films have violence versus how many have religious connotations).

14. The Aviator

When Marty wants to celebrate cinematic history, he does so at full throttle. The Aviator — quite an underrated film by Scorsese’s standards — sees film giant Howard Hughes drive himself to insanity because of his obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Aviator starts off in bipack colour (so everything looks red and green) and it slowly evolves into a more complete colour as the film progresses, making us feel like we are traversing through film history. All of the supporting roles and cameos are welcome, but this is DiCaprio’s moment to shine through the highs and lows of a singular figure; I feel like this was the first Academy Award he should have won. The Aviator is made with care, knowledge, and precision. If Scorsese is going to make a biopic, he’s going to make it right; this is still an example that stands ahead of its peers of the awards season that year.

13. Kundun

It’s easy to overlook Kundun because it’s a rare film that you wouldn’t be able to tell was even directed by Scorsese until you read that credit. A gorgeous, moving, soul-shattering experience, this religious epic about Tenzin Gyatso provides insight into his experience during political and geographical shifts. With top-tier work by both Roger Deakins (director of photography) and Philip Glass (who composed the score), Kundun is easily one of Scorsese’s most enriching films aesthetically. It is even quite sound narratively, although its strengths definitely lie in how you feel this film as opposed to reading it. After Hours is finally getting its major dues, so it no longer holds the crown as the most underrated Scorsese film; that title now goes to the stunning Kundun, which is also a prime example when I prove to people that Scorsese is capable of breathtaking art that isn’t driven by vulgarity.

12. The Irishman

The Irishman felt like it was going to be Scorsese’s final film; I’m glad that isn’t the case. What is most likely his sendoff of gangster films for good, The Irishman is a greatest-hits compilation of what Scorsese pulled off with his earlier epics. Reuniting some major names of the genre (De Niro, Al Pacino [who shockingly never worked with Scorsese before this point], and Joe Pesci [who had retired but returned to acting for Marty]), this deep dive into Frank Sheeran and his involvement in the disappearance — and, most likely, murder — of union leader Jimmy Hoffa. While not everything here works (we don’t need to go into the times where the de-aging effects fail miserably), most of Scorsese’s quest (to reflect on the past via the present by all means necessary) drives the point of guilt home. Here’s an example where it’s impossible to look back without thinking of repercussions because these acting legends play themselves at all ages (for better or for worse): an exercise in turning memories into haunting, ghostly images of where sins destroyed lives.

11. The Last Temptation of Christ

It breaks my heart that The Last Temptation of Christ has been erroneously targeted as a “blasphemous” film when the motion picture seeks to understand Jesus Christ as the mortal human being incarnation of God. If anything, Scorsese and Schrader are deeply religious people. They wanted to depict Jesus Christ’s entanglement with the human experience and examine his mortality amidst his quest to save humanity (while trying to refrain from succumbing to the sins of civilization). Additionally, anyone reading into the fabricated portion where Christ lives a normal life and survives his crucifixion misunderstands The Last Temptation of Christ and what it is saying about the selflessness of a religious figure that is dear to Scorsese: one who gave up his own life in order to save everyone else. Rightfully seen as one of the strongest religious films of its time by today’s lens, The Last Temptation of Christ is an approach to a tired genre through refreshing, impactful purpose and discussion.

10. The Wolf of Wall Street

On the topic of grossly misunderstood Scorsese films, here’s The Wolf of Wall Street: the first film to tackle economic debauchery and failure through meta storytelling, fourth wall breaking, and unreliable narration. Those who think this film celebrates lavish lifestyles and Wall Street thievery don’t know what Scorsese was getting at with this film. Instead, it needs to be read as a horror story of how easy it is to get away with monstrous actions when A) you know how to rig the already-slanted system, and B) you have money. Equal parts hilarious and shocking, this depiction of Jordan Belfort’s exploitations is not congratulatory: it is scathing. It seemed a bit self-indulgent upon release, but The Wolf of Wall Street has already aged tremendously well over the course of ten years because of how much it dives into depravity with tears of both laughter and pain: we live in chaotic, hideous times, and it likely won’t be changing anytime soon.

9. The King of Comedy

Speaking of Scorsese films that have aged well, The King of Comedy only grows better and better with time as the world opens up to the toxic nature of idol worship (especially through such an existential perspective). If Raging Bull was Scorsese’s second wind, then The King of Comedy was his first experiment afterward, and it makes sense within this context that he sought to find out why people become obsessive to the point of insanity. The film was already growing in popularity but it became impossible to shake off when the highly-popular motion picture Joker owed much of its existence to The King of Comedy (even De Niro returns, this time on the receiving end of the idol addiction). With this reappraisal, The King of Comedy fits in perfectly with today’s films of antiheroes, psychological downfalls, and darkly comedic observations of the human condition.

8. Mean Streets

At the time, Mean Streets was unequivocally Scorsese’s breakthrough film: a crime flick that wanted to see how far threats can go before lives are claimed. It achieves so much with so little because Scorsese was already piecing together how to make the most of tight budgets: it was never about the money but rather the expertise behind the tools being used. Additionally, it was already clear that violence was never used just for the sake of it: there was a message of trailing karma waiting to catch up to awful people, all in the name of unforgiving environments that force its inhabitants to fend solely for themselves in the first place. It was the second Scorsese feature to star Keitel and it was clear that the two were meant together; ironically, it was the then-unknown face Robert De Niro, who pops in here for his first Marty project, that would become the definitive partner of Scorsese’s.

7. Killers of the Flower Moon

Over fifty years into his career, Scorsese — a promulgator of American cinema through and through — finally tackled his first western. Of course, Killers of the Flower Moon was never going to just be a straightforward look at the genre. It instead focuses on the real genocide of the Osage community from within: the infiltration of racists who sought to claim the Osage wealth for their own. Its source material focuses on the birth of the FBI in response to the slaughters, but Scorsese’s film instead dials in on one specific case where Ernest Burkhart found himself caught between being in love with an indigenous woman and chasing the blood money via the decimation of her loved ones. It is a snippet of an observation of a wide-scaled massacre that reminds us of the culpability of sin, especially in the face of those we profess to care about. Despite how great the bulk of Scorsese’s filmography is, Killers of the Flower Moon still feels like one of his most daring and challenging efforts to the point that it comfortably sits as one of his finest releases of the twenty-first century.

6. The Departed

Can we stop this theory that The Departed was a consolation prize by the Academy Awards for Scorsese? I don’t care if it is one of his more Hollywood-feeling affairs: this is a downright brilliant film. It is a rare instance where I prefer an American remake to its source material (although the Hong Kong film Infernal Affairs is still terrific and very much worth your time). The film boasts some of Schoonmaker’s finest editing (these two-and-a-half hours feel like ninety minutes because of the blistering pacing and flurry of cuts). This cat-and-mouse (or, rather, rat-and-rat) chase between informants is dizzyingly fascinating, and it never eases up for a break at all. As much fun as it is to watch, The Departed also ensures that it drives home its themes of personal demons and vengeance quite thoroughly. There is no way that this film won out of pity; The Departed is easily one of the best films of 2006, and of Marty’s entire career.

5. The Age of Innocence

If anyone proclaims that Scorsese only indulges in obscenities and disturbing images, here is Exhibit A as to how wrong they are. The Age of Innocence — Marty’s only foray into the costume drama genre (at least in a typical sense) — is one of the strongest traditional period piece films of the nineties: a painfully beautiful, bittersweet look at devotion, desire, and the fickleness of life. Tenderly told and full of both life and spirit, The Age of Innocence is as pretty as it looks. I’m not the biggest connoisseur of nineteenth-century period dramas, but Scorsese provides us with a contemporary approach to a heavily-tried style that is equal parts unique, faithful, and invigorating. With everyone — from stars to crew — operating in top form, The Age of Innocence is a magnificent masterwork that brings tears to my eyes every time I watch it.

4. After Hours

What was once Scorsese’s underrated masterpiece is now a cherished slice of dark, absurdist comedy. What the hell even is After Hours? Almost like Marty’s answer to Samuel Beckett or Luis Buñuel (particularly The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoise), After Hours turns a night out on the town into an abrasively cynical parade of calamities that prevent our protagonist, Paul, from getting home. What starts as peculiar turns into relentless cases of oddity that cannot be the reasons why we cannot get home; furthermore, past incidents return to haunt Paul more and more as all subplots collide in hysterical fashion. While Scorsese leaves us to flounder in this proverbial hell, After Hours is also a tribute to the eccentricities of New York: the city that never sleeps (and neither will Paul this night). I will die on the hill that After Hours is one of the funniest films ever conceived, but I may also be a sadist.

3. Goodfellas

While gangster rap was on the rise, Scorsese released Goodfellas: a cautionary tale of what such a lifestyle would entail from actual testimonies of someone who wanted to be a part of this game. One of Marty’s most stylish films, this rags-to-riches-to-rags epic is stuffed with monumental depictions of pop culture (from fitting songs to costumes and sights). As gorgeous as Goodfellas is, it is also frightening. It is easy to get caught up in the luxury of it all, but that’s kind of the point: Scorsese wants us to be Icarus and also fly too close to the sun. Once we willingly walk into the line of fire, Goodfellas reveals its true colours (mainly blood red). The best traditional gangster film Scorsese ever made, Goodfellas is easy to adore and be shocked by (from its dark comedy to its horrifying scenes of consequence or friction). To see him go from Mean Streets to this film always takes my breath away: he never lost sight of what he wanted crime pictures to state, even with his own fortunes.

2. Taxi Driver

Scorsese’s Palme d’Or winning classic, Taxi Driver, was the release that made him a household name of controversy and the New Hollywood movement. Travis Bickle has been studied for nearly fifty years by the time of this list and it’s easy to see why: he is one of the most fascinating antiheroes in all of film. How much are we supposed to root for him? To condemn him? To understand his actions? The unreliable narrator of all unreliable narrators, Bickle places us in an uncomfortable spot within his own troubled thoughts as he views New York City as the bottom layer of hell in desperate need of cleansing; his quest to be a vigilante petrifies us as viewers, and yet the film won’t stop his ill-natured crusade to be a guardian angel for a city that neglects him (instead, he becomes the angel of death). By the time we reach the oft-disputed conclusion (is this in Bickle’s mind, or is it real?), we know that Taxi Driver is unlike any tale of morality we have seen before; it has spawned many pale imitators since, but nothing comes close to this disquieting opus.

1. Raging Bull

Even though Martin Scorsese has made masterwork after masterwork from time to time again, there is no film that is better than Raging Bull, which I will proudly place on top of the list of the best films of the eighties, the greatest sports films ever made, and Marty’s own filmography. Scorsese himself anticipated this to be his last film because he was dealing with drug issues that nearly cost him his life, so he put everything into this antithesis of a traditional sports film (he himself said he never wanted to make sports films, but De Niro encouraged him to make at least this one). With Thelma Schoonmaker’s best editing to date (with Raging Bull being the finest edited film of all time, in my opinion), Raging Bull becomes an exposition of cross cuts, vantage points, and judgemental long shots that linger, staring Jake LaMotta in the face of his mistakes and self-destruction. The retro style of the film begs us to compare the sanitized way of the Golden Age with the truth behind the New Hollywood movement, creating a contrast between what we are used to and the unorthodox. No question: this is one of the greatest films I’ve ever seen. Every single image has tomes of thought and creativity put into them by a director who thought he was knocking on death’s door, only to revive himself and cement his legacy as an American filmmaking legend. It makes me laugh out of discomfort, reel in pain, and tear up from the glimpses of beauty found within the carnage and humility (case in point: the greatest montage sequence of all time — and the only sequence shown in colour — is beautiful beyond words). I adore this film. Adore, adore, adore it. Raging Bull is an American masterpiece that chronologically documents the declaration and decimation of self within a world that champions fortunes and refuses to help the vulnerable. It is a self-reflection of biblical proportions and a tale of tragedy that has left every audience I’ve ever seen it with speechless (no matter the demographic). It is Martin Scorsese’s magnum opus.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.