After Hours: On-This-Day Thursday

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For September 13th, we are going to have a look at After Hours.

For years, one of the only Martin Scorsese films I hadn’t gotten around to was After Hours, which I frankly didn’t know much about. No one ever talks about this film, outside of maybe a small circle of its fans. On the topic of Marty, however, you’re bound to hear about Goodfellas, Raging Bull, Taxi Driver, and the like. Maybe The Wolf of Wall Street. Maybe The Last Temptation of Christ. Scorsese has conjured up enough films of different varieties that each work has its own audience (unless it’s a Boxcar Bertha or something). These films are usually measured up against his masterpieces, like “there are these films next to Scorsese’s best works that may be worth checking out too”. Well, I’m going to make the case for After Hours today: it should be considered amongst his greatest achievements. I’m talking like potentially top-five-Scorsese material (or at least insanely close). It’s that good.

Right off the bat, it’s Scorsese’s greatest comedy of any sort (it’s a genre that he’s actually quite strong in, to begin with, and if you’re unaware of this, I highly recommend studying his filmography in full). In order for this claim to ring true, the film has to be funny first and foremost. After Hours is outright hilarious. I’ll never forget seeing how the film’s ridiculousness wrapped up in its final moments (don’t worry; there won’t be any spoilers here). I nearly fell out of my chair, which is a fact I cannot say is accurate for maybe any other film in my adult life. How did we get to this point? Well, it’s important to know how After Hours starts off a little bit lukewarm, and then escalates towards this boiling overflow of broth that spills all over your stove; the film goes further by proceeding to waterfall down your countertop, and run all over your tiled floor. Essentially, After Hours is a comedy built on a ridiculous premise, but it runs so far ahead with said concept, that you’ll honestly be astonished by what it achieves. By the end, you, too, will be flabbergasted by the sadistic nature of the tragic comedy here. The hyperbole will have you in a giggle-fit state, and the coupe de grâce will do you in.

After Hours starts off with a date that takes place during the titular time of day: post work.

What takes After Hours even further is what Martin Scorsese is saying here. Writer Joseph Minion actually used parts (and I mean major portions) of his story from a radio drama by Joe Frank; “Lies” while a student at Columbia University; both Minion and Frank were wanting to discuss the shadiness of city life, the oddities of civilization, and the worst sides of human nature. To Marty, this was an opportunity to really get into the nitty gritty alley ways of New York in a way that his other films just couldn’t get to before. There wasn’t some superstar boxer, traumatized war veteran, or anyone else we couldn’t relate to in such a way. Here was Paul Hackett: a poor schmuck stuck in the gears of the corporate machine, who just wanted to try something new this night, by going on a date. Well, his wish gets granted, and we go on said date and see what’s going on.

Naturally, this date falls through (you can just tell Paul’s not the luckiest guy on Earth), and so After Hours becomes a quest about getting back home. That’s when the film really shines, because it allows Scorsese and company to toss in as many relatable curiosities as possible. As outlandish as the film gets, anyone that has traversed a major city at night can vouch for how accurate it all is (I live in Toronto, so not much more needs to be said there). The nighttime scene becomes as suffocating as Paul’s job, when getting home gets more and more difficult to achieve. This evening of promised solace is now a nightmare. Not only that, but the complicated ways that all of Paul’s misfortunes align, connect, and enhance one another is pure art, especially in a comedy this stupid, dark, and pessimistic. It almost feels disgusting to laugh at Paul’s terrible luck, especially since none of us would want this to happen to us (guaranteed). Maybe that’s part of it, too: that it feels like this can happen to us. Even the film’s most ridiculous moments. Because this is life, and life itself just sucks sometimes (actually, quite often). After Hours knows this, and it’s just a slice of such an instance.

The film wraps up with such lunacy, that it becomes a piece of absurdist art.

Considering its a comedy this loony, After Hours boasts a lot of artistic touches: a flex of Scorsese’s that elevates this midnight excursion even more. There is stellar editing here from Thelma Schoonmaker, which lines up with the film’s antsy tension, or in favour of the devilish comedic timing. Some of these moments include the more interesting visions, including a mouse caught in a trap, where this split second causes a moment of empathy for Paul (and ourselves). Even the unrealistic ending still feels like life to us: the endlessness of working a nine-to-five job that barely pays the bills, knowing that we are doomed for the rest of our lives (and not even our evening escapes can save us). For most people on Earth, life is a cyclical drone of eight hour work shifts, and all of the additional hours to try and maintain ourselves so we can do this all again. No matter how out-there your evening was, you don’t matter in the grand scheme of things. Your wild story will only amaze yourself. Society doesn’t care. You’re stuck in this cubicle forever. Home is just the place you leave your stuff.

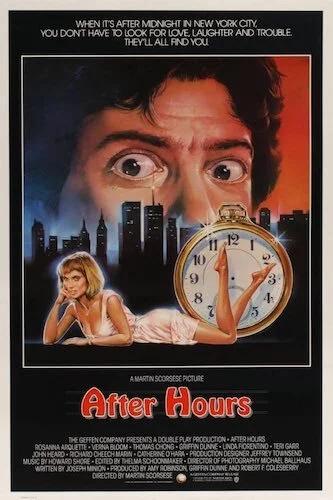

After Hours is so good, that even having a Cheech-and-Chong appearance doesn’t throw the entire film off of its axis. It’s so brilliant, that any amount of obsidian-dark comedy won’t put you off for the remainder of the picture. It feels like the kind of tale you’d hear from a friend-of-a-friend-of-a-friend, but you’re living it yourself now. For one hundred minutes, you’re living your mundane life whilst experiencing this extraordinary turn of events that could only happen to some poor sap like Paul Hackett. As a story, as art, and as a voice of his own about the city he loves, After Hours is peak Martin Scorsese material, and I dare to be proven otherwise. It’s weird to think that a film by one of the most adored directors of all time could be underrated and under seen, but here we are. If you haven’t watched After Hours yet, because its poster seems maybe weird, or because it’s not a Scorsese film people talk about, or because it’s a comedy, I implore you to ignore these nagging thoughts. After Hours may be one of the smartest comedies of all time, and it is most certainly a highlight of the 1980’s. If you’re going through all of Martin Scorsese’s classics and you skip After Hours, you’re doing this all wrong.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.