The Rehearsal Season 2: Binge, Fringe, or Singe?

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Binge, Fringe, or Singe? is our television series that will cover the latest seasons, miniseries, and more. Binge is our recommendation to marathon the reviewed season. Fringe means it won’t be everyone’s favourite show, but is worth a try (maybe there are issues with it). Singe means to avoid the reviewed series at all costs.

Warning: This review contains spoilers for all of the second season of The Rehearsal. Reader discretion is strongly advised.

After Canadian comedian Nathan Fielder blew the doors off of what reality television could be with the first season of The Rehearsal, it appeared that his experiment — to stage potential real-life scenarios as practice runs to vet for all possible outcomes and prepare anxious souls for anything — was a success. In no time at all, Fielder went from helping someone see how they would fare as a mother to breaking open the human experience — what it means to be alive. We act on a daily basis and are forever on edge with anticipation as to what will come next. Fielder suddenly made his own version of Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York, with never ending casting calls, sets within sets within sets, and other forms of over preparation, proving how multifaceted life can be (with endless outcomes). How does Fielder continue from this point on? What else is there to cover? Fielder already tackled the complexity of existence. Doesn’t that entail everything?

We begin the surprising second season of The Rehearsal with a focus on airline pilots, specifically the black box transcripts taken from a plane that crashed and killed everyone on board. Fielder connected with John Goglia, a former member of the National Transportation Safety Board, maybe because he has brought forth the idea of using roleplay to better the relationship between pilots within the cockpit (this is very much in line with Fielder’s concept of staging rehearsals to achieve the best results). It isn’t clear what Fielder’s obsession with this particular topic is at first, but I’m sure any viewer is ready to partake in Fielder’s antics by this point, so, why not cover airline pilots? Of course, Fielder reveals his cards at the best times, both early and right at the end. This way, we can follow along with what feels like an asinine quest before we are proven to be narrow-minded observers while Fielder unearths the exquisite oddities of being alive.

Case in point: it doesn’t take long for Fielder’s six-episode essay to delve into the commonalities between two stranger pilots and both halves of a couple. On an aircraft, pilots work together to ensure the travel and safety of all of their passengers and staff. In a relationship, two people navigate through life together and aim to arrive at the same conclusions. Without communication (Fielder’s chief concern with pilots), how does a couple know what is really going on? Fielder points out that it is the lack of discussion that may lead to numerous airline crashes, including a first officer on board who may feel uncomfortable pointing out a mistake a captain has made, which can lead to problems down the road. Fielder’s point is that there cannot be a breakdown in communication or else a domino effect of trouble will ensue; this is true aboard a plane, within a marriage, and in all other instances where relationships are instilled. The more obvious parallel is when Fielder meets first officer Moody in the first episode “Gotta Have Fun,” who is clearly estranged from his girlfriend Cindy (a barista at Starbucks — no, not Dumb Starbucks). Moody is always traveling because of work and barely speaks with Cindy anymore, and he fears that Cindy will meet a new partner while working (since she is frequently flirted with while on the job). Cindy reveals more to Fielder in an interview than Moody in any form of discussion, proving Fielder’s argument: to not reveal all pieces of information is to hide everything because an obfuscated picture is no good.

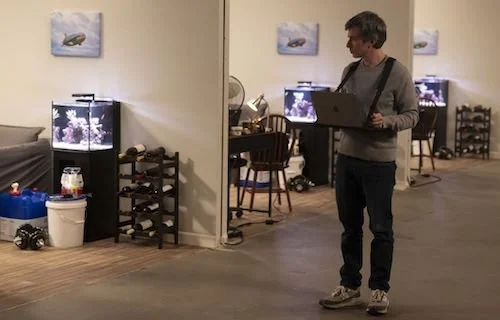

Later on in the season (in the episode “Kissme”), Fielder tries to help pilot Colin find love. He hires a group of actors to play Colin and Emma (one of the hired actors who develops an attraction to Colin) in multiple scenarios. While the fake Colins and Emmas — in recreations of Colin’s apartment, no less — yield different results, some of these actors wind up making out. Some of the Emmas’ boyfriends (their real ones, not the Colin actors) would watch from afar on the set without minding much, since their girlfriends were acting and they didn’t truly love the Colins they were connecting with; this was their belief, but the different pairings had various outcomes. One Emma clearly didn’t actually connect with her Colin and was just taking part in this experiment to help the real Colin and Emma. Another Emma may have actually found a spark in her Colin and isn’t telling her actual partner the truth. What is the full picture here? The complete honesty makes this enactment feel okay, while an obstruction of truth makes the Colin and Emma experiment seem far more gross. A twisting of truth means that there is no truth at all.

While it is an aside, Fielder delves into an ongoing concern in his personal life, using The Rehearsal to air the dirty laundry of Paramount+. Fielder’s previous docu series, Nathan for You, had an episode where Fielder starts an apparel company, Summit Ice, whose clothing is based on the awareness of the holocaust. The gag is a riot, since Fielder utilizes blatant Nazi imagery in the episode to both make a point and create unease. The proceeds from Summit Ice went towards Holocaust Education efforts. Summit Ice was shockingly Fielder’s greatest business venture to date, with thousands of dollars going towards a just cause. Like most other episodes, this Nathan for You entry was a huge success with viewers. Paramount+ quietly removed the episode, which caused Fielder to inquire as to why it was censored. The first response was that Paramount+ in Germany pulled it because the topic of antisemitism was a tricky one in relation to the Gaza war; the other countries that have Paramount+ followed suit. Paramount never gave Fielder a proper response as to how Summit Ice and its affiliated episode are worthy of censorship despite multiple emails, and so Fielder staged a rehearsal to see how he would voice his concerns with the head of operations at the studio; he makes Paramount’s head quarters look like a Nazi base (with the mountain logo replacing swastikas, a map with flags showcasing geographical takeovers [including Netflix’s own “territories”], and the president boasting a thick German accent). If Paramount wasn’t transparent with Fielder, his point was as clear as it could get. Considering that Paramount funded Fielder’s other series, The Curse, it seems that this bridge is now burned.

The Rehearsal’s second season is a fascinating depiction of the necessity of clear communication, regardless of whether or not we are in a cockpit or living our everyday lives.

What does any of this have to do with airline safety? Again, Fielder’s allegory is how humans converse on any plane (pun intended), but there is still a primary focus on the prevention of airline crashes caused by miscommunication. If you think that these asides are unorthodox, wait until we get to what Fielder does when he is focusing on this cause. The least amount of ambition he showcases is recreating all of the George Bush Intercontinental Airport so that the pilots and actors hired for these rehearsals can feel right at home before boarding the plane simulation; he only gets more thorough from this point on. In an effort to better understand pilot Sully Sullenberger, who famously, safely navigated a failing aircraft onto the Hudson river, Fielder initially wants to just examine the incident itself. After talking to a couple who cloned their dog after he died, Fielder notices that the cloned dog is unlike the original in behaviour. This is because the clone had a different upbringing, resulting in a new personality despite the identical genes.

As a result, Fielder recognizes that simply acting as Sullenberger during the crash landing isn’t authentic enough. Fielder instead recreates Sullenberger’s entire life based on the pilot’s memoir, Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters. Fielder even shaves off the majority of his hair and becomes an infant version of Sullenberger, being breastfed from a massive and haunting puppet. Fielder goes through all of Sullenberger’s life leading up to the crash, and through this bizarre project and the scrutinizing of the memoir, Fielder can even deduce why there is a pause in the discovered transcript of the landing: he believes that Sullenberger was listening to rock band Evanescence’s “Bring Me to Life” on his iPod, thinking that he may never have a chance to listen to the song again. Fielder’s methods may become ludicrous, but they get results when it comes to understanding how strange and transfixing we can be.

On the topic of music, Fielder concludes that there is a certain vulnerability within the medium: a baring of one’s soul when they belt out melodies and lyrics. Perhaps he came to this conclusion during one of his earliest jobs (working as a personal assistant on the singing competition show, Canadian Idol). As an effort to get pilots (not actors, real pilots) to fully open up, Fielder hires a handful of first officers and captains to judge singers in the strange show-within-a-show, Wings of Voice. In return, Fielder also asks the singers to rate their judges on a scale of one to ten; this request garnered some blunt and honest ratings. Fielder himself gets skewered with brutal scores; he surmises that he can learn better communication tactics from the other pilots. After numerous attempts to get better at delivering singing hopefuls rejection, he is gifted one last score: a six (or, Fielder hopes, a nine, which it can easily be when flipped upside down). If communication is made by a deliverer and a receiver, and the latter can create their own perceptions, the act of discussion is as much about what is being heard as it is what is being said. If we can concoct our own messages based on the information given to us, even if this results in dishonesty, how can the sender ensure clarity that cannot be misconstrued?

As Fielder works on himself time and time again to become a master of communication, he’s not only figuring out the best measures for pilots: he is preparing for a meeting with any congressman willing to hear out his pleas for change. By the penultimate episode, “Washington,” it is clear that Fielder does have a point about the importance of transparency within the confines of an airplane’s cockpit, since many lives depend on the two pilots upfront. After numerous efforts to be seen, Fielder discovers online that his first season of The Rehearsal helped many members of the autism community live their everyday lives; they felt seen. Fielder uses this as an opportunity to become affiliated with the Center for Autism and Related Disorders and connect with a congressman who appreciate this effort more than the push for airline safety (more on this venture later). After hooking politician and attorney Steve Cohen via both of their roles in the spread of autism awareness, Fielder shows how the meeting went. Fielder dishes out everything he has when it comes to the importance of better pilot protocol and communication; Cohen zones out and winds up scrolling through his phone at one point. The mission to get Congress on board was a clear failure, but at least Fielder has his show that can act as a vessel for this same information; I may not be Cohen, but I believe that Fielder makes many credible points.

With all of this in mind, we aren’t even at the most baffling revelation and stunt found within the whole season (and, really, Fielder’s entire career). The hour-long season finale, “My Controls,” features one brief moment where Fielder discusses his affinity for magic stemming from a young age when he used to put on shows. The art of magic is the concept of misdirection, fooling audiences into believing something they haven’t fully comprehended. In the first episode of this season, Fielder discusses how his efforts may not be taken seriously because he will always be seen as a comedian first (and comedians are never fully listened to, since they are expected to be funny and not truthful: an awful misconception, since I believe that humour can deliver some of the strongest doses of honesty, and Fielder may agree). The whole season, Fielder’s qualifications within the airspace have come into question. It is only in “My Controls” that Fielder drops the biggest revelation of them all: Fielder knows what he is talking about. This is because he spent the last two years becoming a licensed pilot. Yes. I cannot believe it myself, either, and the episode shows all forms of proof to certify this claim.

Holy. Shit.

While it takes a number of loopholes to discover for Fielder to be able to pull off his stunt, he spends years preparing for the massive gamble of successfully flying a Boeing 737 full of passengers (hired actors, but they are flying in the sky with him no less) from the San Bernardino International Airport, to the border of Nevada, and back. Even though it is clear that this trip would be a successful one, I was still shaking in my seat anticipating how this flight would go. Fielder has made me laugh many times, and his discoveries have certainly made me get teary-eyed. However, this is the first time ever that Fielder had me feeling weightless with thrills, completely flabbergasted with what I was watching. As if the quest to fly and land a plane wasn’t incredible enough, it is what happens within the cockpit that ties the whole season together. Fielder flies with first officer Aaron (who happened to also be one of the Wings of Voice judges, and a pilot who has an interest in television, hence why Fielder picks him). After takeoff, Aaron furrowed his brow and stared off into the distance. Fielder opens up the conversation by asking what is on Aaron’s mind; Aaron dismisses this glance as just a form of concentration. After Fielder encourages Aaron to partake in an exercise (one used on some of the other pilots earlier in the season), the truth comes out: Fielder forgot to tuck in the flaps of the wings after takeoff. By God, Fielder’s madness works once again. Had Aaron kept holding in all of his concerns and Fielder kept making mistakes, perhaps we wouldn’t have had a finale to watch at all. Fortunately, the plane lands, and all is well.

A major talking point throughout this season is the reluctance pilots have to share their feelings not just out of intimidation of those with power over them (veteran co-pilots, for instance) but out of fear of job security. It is insisted upon time and time again that any formal diagnoses of mental or biological illnesses can cost pilots their job since they will be deemed unfit to be responsible for the lives of others. This inability to ask for help or clarification also leads to the disruption of the flow of information from one pilot to another, including suggestions and the raising of concerns; as if the distress caused by revealing too much makes all forms of confrontation daunting. While at the Center for Autism and Related Disorders, Fielder is encouraged to partake in some tests that determine if any takers have autism. Fielder doesn’t do the best with the couple of questions he tries his hand at, hinting at something that we believe will be covered in the season’s finale. While filling out a mandatory form to prove his mental and biological fortitude in preparation for the flight of the 737, Fielder comes across a part of the questionnaire that asks if he has mental health issues. He undergoes a fMRI to see if maybe, after all that, he has always had autism that he never noticed (which may explain why he has never felt comfortable with how his social skills are perceived, like the lukewarm and brutal scores he was given as a Wings of Voice judge). The results won’t come until after the 737 flight is scheduled, so Fielder goes ahead and applies for the flight (we all know how it turned out).

Towards the end of “My Controls,” Fielder gets told that the results are ready, long after the 737 experiment occurred. Knowing that being formally diagnoses with any form of mental illness will cost him his newly found passion for aviation, Fielder deletes all traces of correspondence and forgoes finding out what he was about to learn (again, truth can be manipulated by both the sender of information and the receiver; in this case, Fielder cannot digest that of which he doesn’t know). Now, I think anyone can figure out that you cannot actually diagnose autism via an fMRI and the process is far more complicated than this, but Fielder clearly hired this specialist for the message within the episode: how can one person’s opinion or one small diagnosis cost a worthwhile pilot their job? I understand if there is a damning piece of evidence, but simply having autism or anxiety should not condemn a pilot who has undergone all forms of training to get to this point (as per Fielder’s studies, are classes, lessons, and test runs not rehearsals?). By never finding out if Fielder has autism (or any other mental condition), he has been able to fly numerous planes since. He concludes the episode — and the season — with the sentiment that he is fine, because “no one is allowed in the cockpit if there's something wrong with them." He is allowed in the cockpit.

His point was never that those who fly planes are unfit if their choices lead to accidents: it’s that there should be a process to avoid crashes or other mishaps and that there is something worth discovering with each pilot as a result (a stronger bond between professionals that can garner greater results). By becoming a pilot (via living the life of an iconic example, and also, you know, literally becoming a pilot) and undergoing a myriad of experiments that actually amount to something, Fielder has many reasons to speak on the floor of Congress about this particular issue. Sadly, he wasn’t given the opportunity to be heard. Then there is Wings of Voice, with the crowned winner, Isabella Henao. Henao went on to sing what has become Sully Sullenberger’s anthem, “Bring Me to Life.” Not only do we hear the start of a singer’s career on television, we witness the most vulnerable moment of Sullenberger’s life when he was almost certain he was about to die and wanted to hear his new favourite song just one more time; Sullenberger’s experience was, indeed, brought to life. In an AMA session on Reddit, Henao remarked that she was experiencing throat problems when this performance was recorded, but this imperfection only makes the likeness with Fielder’s flight all the stronger (Fielder wasn’t perfect, but he stuck the landing, as did Henao performing a song in a style she is not accustom to). In the same way that Fielder was applauded for pulling his stunt off, Henao is cherished for winning the competition (a fake one, if you will, but one nonetheless).

We got the ending of Fielder’s congressional efforts, his flight stunt, and Wings of Voice: just not his supposed diagnoses. We understand that dialogue is to be open, but we also learn that there may be exceptions: if they jeopardize our well being and can be avoided. In this instance, not saying something says everything, so even then, Fielder is being open with us. In a weird way, it’s as if he doesn’t want to be deprived of his successes again after that Paramount+ nonsense surrounding Summit Ice. Censorship is the intentional deprivation of information or opinion, after all, and Fielder’s mission is to create complete openness. Does “My Controls” render Fielder a hypocrite? I feel like it is akin to his knack for creating grey areas since nothing is ever black or white. When is it okay to close up and not leave it all out in the open? We are left with that thought in the season finale of a show that remains one of the greatest achievements on television right now.

What started out as a silly perspective from a cringe-inducing comedian became the ultimate test by an actual pilot. He admitted that he wasn’t taken seriously as a symbol of hilarity, but I felt compelled to revisit the entire season once I learned that he was actually a licensed pilot this whole time (not that I wasn’t already listening to what Fielder had to say, mind you, but his point on perception is appropriately apparent). Fielder has always known what he is doing. Even if there is a sense that there are hundreds of hours of footage and Fielder makes the most with what he has, his ability to create purpose within madness has resulted in magnificent television time and time again. Whether you feel inspired, gobsmacked, or outright confused, The Rehearsal is guaranteed to make you feel something. Despite being known as the comic figure who almost feels alien, I assure you that there is no one more human than Nathan Fielder on TV. You may watch The Rehearsal to learn more about him and his methods, but you will always wind up learning more about yourself. This whole series is devoted towards analyzing us as meticulous beings, and with the ambiguous ending, Fielder instructs us to come up with our own meaning; we are brilliant creatures, after all. If Fielder can fly a fucking plane, we can make our own conclusion of “My Controls;” it is now in our hands.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.