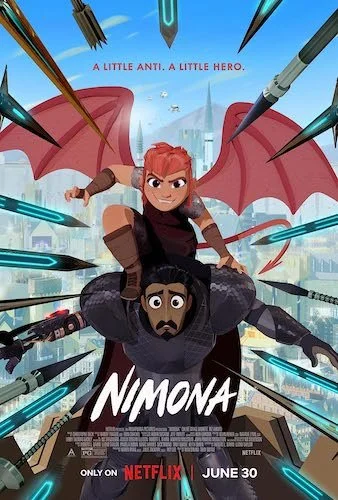

Nimona

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

The latest Netflix release making noise is the animated feature Nimona by Nick Bruno and Troy Quane formerly of the now-defunct Blue Sky Studios. This project was in development for years underneath Disney’s prevue until the House of Mouse distanced itself due to the LGBTQ+ themes of the film (because Disney will only go so far with full representation like hands being held or one line of dialogue and then call it a day). Netflix — itching for originals that won’t tank — picked up the project along with Annapurna Pictures (a name I haven’t heard in quite some time; that static TV logo was such a blessing to see again). It was a silent release that exploded upon impact: everyone began discussing Nimona overnight. It’s easy to see why Nimona created such buzz, from the friendly hat tip to the ways of traditional animation (it’s still CGI but not overly so) and the feisty energy of the titular shapeshifting character, to the upfront approach to societal topics that many family films try to stay away from entirely. You can claim bigotry for the last point, but I honestly feel like many family film studios or storytellers don’t quite know how to tackle such sensitive topics head-on, but the real issue here is that those who brush against LGBTQ+ representation barely even try to do anything else outside of serving appearances to hush outcries.

Nimona is the real deal and actually has something to say about intolerance throughout history and even in the present day. It possesses a bite to what it says as if it really doesn’t care about any opposition. Why should it? Those that don’t want to watch this or let their kids see it won’t, so Nimona will likely be viewed by those that actually agree with its statements on instilled hatred. It shouldn’t feel the need to hold back when we’ve done enough of that for centuries. Nimona is all about inclusion, and it’s a topic that’s been tiptoed around or feigned for far too long: of course those telling the story have a frustration that seeps through the frames here.

Based on the graphic novel of the same name by ND Stevenson (who has discussed his own experience with being transgender in the webcomic I’m Fine I’m Fine Just Understand), Nimona isn’t subtle about what it is saying about toxicity but it still has interesting ways to incorporate very real allegories into its hybrid story. In a medieval community in the future (already off to a headstart with the idea of society living in the past and holding itself away from the capabilities present), we follow a regular commoner, Ballister Boldheart, who is due to be knighted. Members of society are angry because he is an everyday person being used as an example by Queen Valerin that we are all heroes if we choose to be. During the ceremony, Queen Valerin is assassinated by the sword Boldheart possesses despite him not trying to kill her at all. He has been framed. He goes into hiding to avoid capture and while he conceives a plan to clear his name, he is visited by a seemingly bloodthirsty girl named Nimona. She reveals herself to be a shapeshifter capable of embodying any being she desires. She sides with him because she knows what it is like to be cast out by society. While Boldheart is initially disinterested in her help, he finds a great, misunderstood friend in her. Together, they try to prove Boldheart’s innocence to the masses.

While it relies on some usual family film tropes, Nimona is commendable for what it dares to do unlike many of its contemporaries: house a real conversation about acceptance.

Boldheart is in love with Ambrosius Goldenloin, who is the heir of Gloreth: a beloved knight from yesteryear that helped hold out the monsters from this kingdom. Goldenloin unfortunately initially believes what society says about Boldheart, especially with the Director of the Institute for Elite Knights and her commands to seize him (this is a society where everyone does as they’re told). Additionally, Nimona herself is a symbol of transgender identity and gender fluidity as she often rejects being called a girl, a monster, or anything but her name; she wants to be whatever she chooses at any given time. There are clever integrations throughout Nimona, from society being full of white knights and held in via the keeping of gates, to the virility of cancel culture and victim shaming. I feel like the comedy and characterizations are a little more traditional, as the catch-phrase-spewing Nimona will say the first thing that is on your mind (but Chloë Grace Moretz’s infectious voice acting will make you not mind too much), and the jokes often lead exactly where you predict they will. There are also inclusions of popular songs that feel on the nose, but I can’t complain when Nimona dances in shark form to “Gold Guns Girls” by Metric (that sequence is still stuck in my head) and Judas Priest’s “Breaking the Law” is used as a punchline (at least they didn’t erroneously call them death metal as something else has). Nimona herself adores metal, and I couldn’t expect a family-friendly film to get more metal than this (but it’s something).

The story itself is similar: strong in some ways and safe in others. While some bold turns are indicative of a toxic society and our banishment back to square one because of backwards mentalities, there is also narrative sameness, but we have to start somewhere with this conversation in such a capacity, right? As it stands, Nimona is commendable. In its hour-twenty runtime (ignore the super long credits when it comes to the runtime: Nimona is quite short), the film goes through a lot of airing of grievances, soul searching, and discovery of hope within hostility. Because of how diverse the film is, you can get something out of the film even if you aren’t a member of the LGBTQ+ community whether it’s the acceptance of race, class, faith, and many other identities. Nimona is a film for allies, and it’s clear as day what it is trying to get at and how it will get there. I think a film like Nimona was made in hopes that there will be changes of heart with the viewers that have regressive views on love. We live in a particularly testy environment and era so who knows, but I think Bruno and Quane can dream, right?

At least this important discussion is being had: we can’t dance around the safety and well-being of others when their identities continue to face hatred even to this day. If Nimona has to convey this message in a cookie-cutter way that many will understand, so be it: it’s still at least somewhat more courageous than its contemporaries. Observing the film just as a family feature, Nimona is a loving-yet-fed-up film that just wants everyone to live happily and it is conveyed via warmth and ferocity, the latter being either cute or dead serious (depending on the tone of the scene). Of course, Nimona was going to start trending: it’s the refusal to give up a very real fight via a likeable vessel. Expect Nimona to be cherished for the remainder of the year come awards season time; it may not stand a chance to win the big prizes, but it will likely be championed just to celebrate its necessary existence and highly-addictive nature.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.