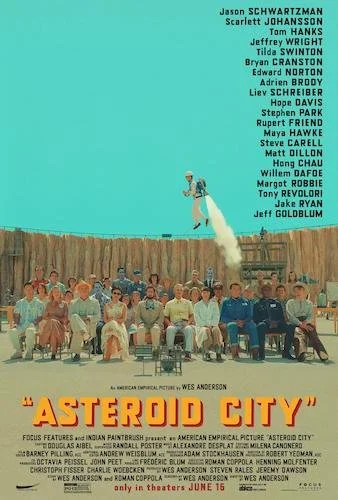

Asteroid City

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Have you noticed that the overall reception of Wes Anderson as a filmmaker has ebbs and flows? When he first burst out onto the scene, there wasn’t anyone like him and he was beloved instantly (with Bottle Rocket and Rushmore being instant nineties classics). After The Royal Tenenbaums, the tides turned against him and he was suddenly being met with mediocre reviews for The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and The Darjeeling Limited. After Fantastic Mr. Fox, he was the poster child for great, idiosyncratic cinema once again. This would continue until The French Dispatch was met with shrugs (but, to be fair, this is his weakest film while still being a nice watch). Asteroid City, the Houston auteur’s latest release, is similarly being dismissed by enough critics (although to be fair, some reviews adore this film), so I must pose this complaint once and for all:

Can we stop making Wes Anderson a temporary, fashionable trend and start treating him with the constant treatment he deserves?

I understand that his films evoke specific sensations and aesthetics of whimsy, but he has not once wavered stylistically his entire career. I believe the masses may feel alienated by his specific style but they come around when he releases something friendly (Fantastic Mr. Fox) or impossible to ignore (The Grand Budapest Hotel). When he goes full-on W.A., it’s suddenly time to hide again. Look. Wes Anderson has always remained true to himself. If he was suffocating at his peak level of self-awareness, then maybe I would find some validity in these reservations that critics have every so often, but consider how The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and The Darjeeling Limited — his two worst-reviewed films upon release — are welcomed with open arms now as misunderstood gems of his filmography. I don’t think this has anything to do with the films aging better than they were released. I think society determines when they feel like they want more Wes Anderson or not. It’s stupid, and I don’t think many filmmakers get this sort of response the way Wes Anderson does.

Case in point: Asteroid City is really good, and I firmly believe it will be revisited in the future the same way the two aforementioned “duds” have been. It doesn’t have glaring problems like The French Dispatch (which had three underdeveloped vignettes within an even thinner over-arching theme), yet it isn’t quite the fully realized films that Anderson is capable of (The Grand Budapest Hotel, Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums). I keep bringing up The Darjeeling Limited and The Life Aquatic because Asteroid City nestles nicely in this company of films: Anderson’s stories that are full of heart and poised drollery that are misunderstood as pretentious because they are near and dear to the filmmaker’s identity of self.

Asteroid City’s meta nature opens up many reflections of existentialism and fear in an era full of dread.

Asteroid City is actually a televised play within the feature film by fictional playwright Conrad Earp, and this motion picture includes a behind-the-scenes analysis (“reenacted”, of course) via an anthology series detailing how the final production came to be. This observation — led by Bryan Cranston as a nameless host that you swear came from the fifties — feels as though we are watching a documentary of an episode from Playhouse 90 or the like. You feel properly transported in the mindset of the nuclear age, as Anderson provokes you to start considering your own time and place as you watch Asteroid City: how different are we from this one decade once synonymous with fear-mongering?

The play-within-the-film introduces war photographer Augie and his family who have recently learned that their mother is dead (Augie already knew but neglected to tell his children until this very point). Augie doesn’t see eye-to-eye with his father-in-law Stanley, as if they both represent two different generations in post-World-War-II America (I think the subtle career as a war photographer is Anderson’s way of implying Augie’s political stance when a nation was asked to fight). Augie and his children were en route to the Junior Stargazer convention when their car breaks down and they stumble upon actress Midge Campbell and her daughter (also heading to the event). Without giving too much away, Augie and Midge’s highly-intelligent children connect as do these lonely parents, and the convention opens up a whole new can of worms once all of the participants experience more than they bargained for and everyone gets caught up in a state of national hysteria.

Behind this play is Earp and the major actors partaking in this production; Jason Schwartzman is Jones Hall who plays Augie; Scarlett Johansson is Mercedes Ford playing Midge. There’s also Schubert Green who is directing this play in his problematic way; his sexist, backward approaches to directing are indicative of show business and its tendency for hypocrisy (imagine trying to tell a story about progression in the United States when you yourself are hindering progress). This metaphysical approach to storytelling allows Anderson to frame certain characters in specific lights: Jones Hall begins to contemplate his own reason for existence once he loses sight of his role’s motivations mid-production. Augie’s deceased wife is shown only by a photograph, but her actor (played by Margot Robbie) is seen outside on a balcony during a break from another play; her lone moment in Asteroid City is cut (a dark statement from Anderson on the matters of one’s existence before and after death). This wife character (who isn’t even blessed with a name) remembers her sole line, but that doesn’t matter when she is snipped out of reality; her legacy and history still matter to us, and Anderson wanted to at least assure us of this.

Wes Anderson gets self-aware not just in an artistic way but as a human being with Asteroid City. In the confinements of the play, we see a society of forward-thinkers suddenly get caught in a standstill and forced to think about where we’re at as a civilization and as people. Behind the play, we find artists and storytellers flummoxed with how they want to best tell this story to the masses. Behind the behind-the-scenes is middle-aged Wes Anderson still gazing at the world with his curious, unfeigned vision. He can’t help but inspect the overall dread the world is facing with so many apocalyptic events looming over us, but he also doesn’t want to instil fear (he also touched upon the notion of a gloomy future in the even more serious Isle of Dogs, so this isn’t exactly out of his comfort zone). He also touches upon death quite a bit in Asteroid City: another topic he’s no stranger to, but he provides an effective angle he hadn’t realized before here (particularly the fickleness of a society that moves on once we go, with the threat of an astronomically scaled wipeout that would render us forgotten as a species, even if Asteroid City never goes full on The Day The Earth Stood Still on us).

On that note, there’s a certain poignancy found in Anderson’s restraint from making. a full-on space invasion picture particularly with what he’s saying about society’s propensity for overselling fear in the wrong areas (we’re forced to move on while we grieve in a climate that refuses to wait for us, and yet we must displace our sadness and fright in the compartments society tells us to). At the same time, Anderson doesn’t outright hate humanity as some other cynical storytellers do, and he never really paints humans as complete idiots here; nay, they are complex beings in the same way we view that “visitor” in the film (perhaps he views us the same way: flesh vessels that are unaware of the otherworldliness that we possess). Asteroid City is just as out there as Anderson usually is, but it also carries this tenderness he occasionally projects (and it’s this very warmth that is usually met with tepid reactions upon release but is appreciated as the years come and go).

While I do feel like Asteroid City could have gone even further with its deep topics, I think Anderson goes far enough to land yet another great film in his career. Inspired by the fuzzy, square, black-and-white visuals of televisions past and the green-red Technicolor of fifties cinema, Asteroid City is yet another aesthetic feast for the eyes (but Anderson has never let us down in this department). I feel like this massive cast is properly utilized for the most part where even the bit parts (Robbie, Willem Dafoe, Hong Chau) carry some sort of purpose and meaning (lest we forget Anderson alum Jeff Goldblum as a being from another planet which is pitch perfect casting even in this brief part). It’s cheap to just call this Wes Anderson being Wes Anderson because his usual gimmicks don’t feel like they are wasted: you can argue that there is careful thought in every actor cast and in every aesthetic choice (even Alexandre Displat’s cutesy score carries some sci-fi twang and an eerie, beating pulse that kicks in precisely when needed).

If we’re going to be seeing many films about society’s concern for its own safety (and we already are), then Asteroid City is a non-condescending example that we could afford to have. It respects us as the easily-scared animals that we are and sees us as individuals wanting to be loved while alive and honoured when dead. Anderson will never forgo his cinematic magic and affinity for innocence even when he has something real to discuss, yet he also doesn’t dial his philosophies back enough to the point of vapidness. We get the perfect middle ground: a deep conversation that is told from a point of adoration and without pointed fingers and scorn (it’s almost more courageous this way). Asteroid City demands to be seen as it is and not with the skewed lens that Wes Anderson is currently uncool (which is also just flat-out wrong, I may add), especially since it is some of the deepest soul-searching the director has ever committed to film. Watch: Asteroid City will be properly approached years from now, but this wouldn’t be the first time Wes Anderson has faced such a stupid fate. The film should at least be properly understood and analyzed now; liking the film is a whole different story, but it deserves more than a cold shoulder.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.