Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Alejandro G. Iñárritu Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Fame

Uncompromising. Visceral. Unmatched. The films of Alejandro González Iñárritu are unlike the films of so many filmmakers. Sure, other directors can be cynical and darkly comedic, but the Mexican auteur has a signature take on the worst qualities of the human psyche. Whether he channels the drive found within human suffering (as lone wolves fight to survive) or the weight of the world as it stares and laughs at its gawks at tortured souls, Iñárritu depicts the fickleness and bitterness of society so starkly. I can’t even really call these films melodramatic despite how extreme its subjects and portrayals are because they don’t feel theatrical or unnatural: somehow, even at their most fantastical, Iñárritu’s films are still rooted in reality.

At the start of his career, Iñárritu seemed to be the next kind of multi-narrative storytelling with a few films that had interwoven lives collide in different ways. By the 2010s he was genre bending more than ever before, particularly with the film that he would win Best Picture for. It’s as if he was starting to find comedy within tragedy because of how intense his films became; hysteria does refer to both the contagiousness of collective excitement or the spread of panic amidst turmoil. No matter what film of his you see, you will feel affected in some way. Oftentimes his films have been described as harrowing, disturbing, or simply too much for some viewers, but that kind of proves my point: it’s impossible to not be changed after watching any film by this contemporary master. Here are all of the films by Alejandro G. Iñárritu ranked from worst to best.

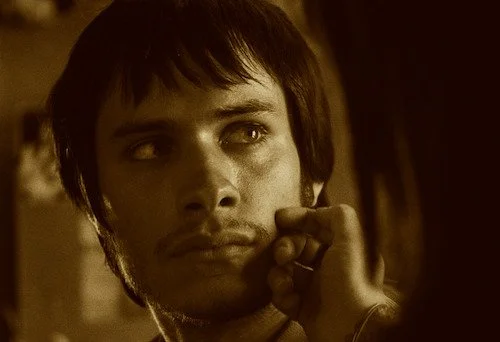

7. Biutiful

Even the lowest ranked film here is one I do recommend, but Biutiful is the only time where I feel like a work by Iñárritu is a little too much. It wallows — unlike any other film of his — in misery and grief, and I feel like you never really get to know lead character Uxbal more than you do from the expository sequences that open up each aspect of his life. Once Biutiful gets going, it kind of runs in circles and forces Uxbal to deal with the predicaments he finds himself in again, and again, and again. There’s exposing cinematic suffering, and then there’s getting nowhere with it. While this may be the weakest Iñárritu film in my opinion, it is a major highlight for star Javier Bardem who carries the entire picture on his shoulders. Once diagnosed with incurable cancer during an already challenging chapter in his life, Bardem’s Uxbal embodies sadness, rage, and torture so earnestly. Iñárritu also shines in the film’s down moments: the few glimpses in Uxbal’s unfortunate life that remind us that life itself is forever “biutiful” even when it seems anything but.

6. Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths

While labeled as an indulgent film, I may have a more positive connection with Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths than many viewers have. Semi-autobiographical in nature, Bardo depicts a filmmaker and his surreal meta-world that doesn’t operate anything like ours. In fact, it’s quite nightmarish. However, it’s rooted in the ideas of an ailing mind that blends one’s subconscious with their everyday life, and I don’t think Bardo has gotten enough credit for the many things it does right. Is it a bit overlong? Sure, but Bardo feels like the closest thing we’ve had to a film by Federico Fellini in quite some time (while not being quite as successful in its experimentation, mind you). Besides, I think this idea of “pretentiousness” is ridiculous: who doesn’t want filmmakers to try their best? I think give Bardo some time and the hostile reception towards the film will cool down. In fact, it may even be loved in time.

5. 21 Grams

We’re leaping up in quality here with the first great film of this ranking. The first English language film by Iñárritu was an instant sensation when it came out. Now? 21 Grams is a little under discussed. Following a hit-and-run, you see how various lives are affected and the downward spirals that transpire afterward. It really is the sister film to Amores perros (it does make up the “Trilogy of Death” with Babel as well, after all) in the sense that the “incident” itself isn’t the biggest tragedy: the repercussions are what are the biggest curses here. Featuring groundbreaking performances by Naomi Watts, Sean Penn, Benicio del Toro and more, 21 Grams was a huge shakeup during the awards season. It may feel a bit like Iñárritu was figuring out how to connect with American audiences for the first time, but even this preliminary attempt is a great one: he instantly figured out our greatest dreads in one try.

4. Babel

Want to know why I think Bardo will be loved over time? Because Babel has a similar reputation, although it actually was nominated for many more awards when it was released (it actually won quite a few as well,like the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture — Drama). Even still, Babel had a bit of a split reception: is this film really as good as its accolades would dictate? It was certainly Iñárritu’s most ambitious film narratively upon release (in fact, it may still very well be), as you see the domino effect from one poor choice; this time, the damages can be felt across the entire world and over the course of numerous months. At first the four stories don’t really seem to correlate, but they have everything to do with one another, and Babel’s slow revelations are subtle, natural, and incredibly effective. I think the main thing is that the first watch of Babel has viewers wondering where this epic is going, but watch the film again and everything will click into place: we are all tied by our decisions whether we realize it or not. Babel has aged tremendously.

3. Amores perros

Where it all started. Iñárritu’s debut film hits the ground running. It is two and a half hours long, already starting the multi-narrative scheme that Iñárritu would quickly become synonymous with (he actually perfected the idea on the first try), and as devastating as anything the then-new director would ever craft. There’s no sugar coating or testing of waters here. A triptych of stories collide via one event, but the protagonists of each tale were struggling already; if only they knew how much worse things would get. Riveting to the point of being impossible to ignore, Amores perros grips you from the start. How many debuts are this confident; this daring; this visceral? It would set the mold for Iñárritu; while he would stray away from this blueprint at least a little bit with each subsequent film, it was clear from Amores perros that the Mexican director embodied agony unlike anyone else.

2. Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)

It says a lot when Iñárritu’s lightest film is Birdman: a tragicomedy which is still brutal. What I will say nine years after its release is that Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) is a genius concept executed superbly: the blending of the stage experience and popcorn blockbusters in such a homogeneous way. With Emmanuel Lubezki’s illusion of a single, long take, powerhouse acting (particularly from Michael Keaton), and this sense of vulnerability, Birdman feels like we are on Broadway watching greats go to work. The film never forgets its actual medium though, as it succumbs to its big screen ways in such effective sequences. As a washed up actor tries his hand with the theatre industry much to the chagrin of many, his existential dread heightens unlike ever before. One of the most imaginative films of the 2010s (and one of the more unique films to ever win Best Picture at the Oscars, where it cleaned up), Birdman talks the talk with its big ideas and follows through with the best walk it could muster; it actually wanders into territories you'd never expect, and getting lost in the depths of insanity has never felt so comforting.

1. The Revenant

This western doesn’t ease up, does it? Based on the real survival of Hugh Glass (whilst being based on Michael Punke’s version of the events in his novel of the same name), The Revenant is one of the most unabating cinematic experiences of the twenty first century. From watching Glass’ bear attack in full (claws, teeth, blood and all) to many other gruesome acts that precede and follow, The Revenant becomes more than just one person's quest to stay alive: it transforms into a mission of vengeance in an unforgiving world where the only hopes for humanity come in the form of the sunset’s rays blessing the glistening, crimson corpses of the damned. Spearheaded by one of Leonardo DiCaprio’s finest performances (I don't care what anyone says) and Lubezki’s singular cinematography (the use of natural lighting here, while a pain in the ass to shoot, is unparalleled), The Revenant is so tortured that it almost feels euphoric: pain to the degree of numbness. It is as exquisite as it is horrifying, and not many filmmakers can pull it off in the way Alejandro G. Iñárritu does here. To me, The Revenant is his finest film, although he has a few features that come close; distressing doesn't even begin to describe this one.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.