Living

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

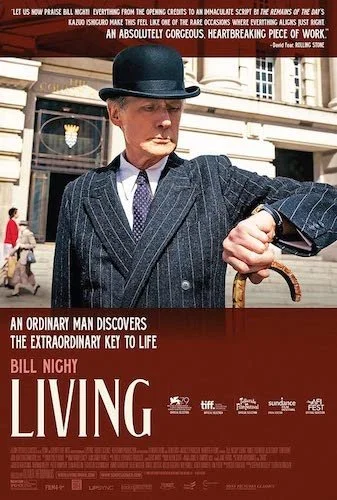

It was inevitable that any adaptation of Akira Kurosawa’s masterful Ikiru couldn’t compare, and it feels almost foolish that one would even attempt to try such an undertaking (especially around seventy years later). Well, I’ve finally gotten around to Oliver Hermanus’ attempt, Living, and I can safely say that, no, this isn’t as good as the Kurosawa opus, but it at least feels like it matters. Right from the opening titles for Living I could tell that there was an effort to make this feel noteworthy, although I was hoping that the 50s film illusion stayed throughout the entire film (but hearing that music and seeing those transitions took me back to the classic era). Throughout Living, I could feel tributes to Kurosawa, including particular shots (one squarely framed, low angled shot of Bill Nighy from above is an example), but I also sensed at least some other inferences of the 50s era, ranging from the film’s colour palette and fuzzy cinematography to Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch’s score.

Kazuo Ishiguro’s screenplay keeps most of the ideas of Ikiru here, although his affinity for pontificating one’s importance in the world (as can be seen by his brilliant novel Never Let Me Go) does take the wheel here. While Kurosawa’s film is more about the insistence to keep living and to have one’s legacy live on for them as a second wind, Living — as per Ishiguro’s writing — focuses more on making the most of one’s final days alive. Nighy stars as Mr. Williams: a bureaucrat that keeps to himself that has been told he has six to nine months left to live due to his terminal cancer. One thing that is the same between both films is how this central character experiences a change of heart and realizes what he must do to make the most of his remaining time (I wouldn’t dare spoil one of cinema’s greatest symbols, which Living includes faithfully). What feels quite different is how Living presents a pleasant world that Mr. Williams is sadly going to be departing soon despite its problems: Ikiru is quite cold, but brightness is found in this race against time.

Bill Nighy is reserved yet effective in Living: a film that could have been all about winning awards, but instead tried to actually be truthful.

Nighy as Mr. Williams is splendid. I’m not sure what I was expecting from a charming thespian with such a reputation for being pleasant, but I think I couldn’t shake off the feeling that an adaptation of such a classic was likely going to be Hollywoodized, but Nighy not once tries to steal the scene. He just exists, and Living benefits from this performance as a result. There are no Oscar-stealing moments, and yet Nighy’s Academy Award nomination feels so justified because of how real he is here. He operates entirely within his own head, and you can read his mind race a thousand thoughts a minute while life passes him by. If there was any element of Living that feels the most like Ikiru, it’s how Nighy commanded himself the same way Takashi Shimura would (and did) in this role: not by wondering how the performance would look on screen, but by how it reads as real life (by letting the film do the rest of the work to connect us).

Nighy is tender and moving in Living, and while there are quite a few reasons to see it (an adaptation of an untouchable film that miraculously doesn’t feel pointless being the main one), there’s no denying that he is the man of the hour here. This is felt in spades towards the final act of Living: one that depends on the lasting impact of what we’ve seen before. Living’s attempt at what Ikiru invented is a good one, and you’ll be sure to feel at least significantly impacted once the credits begin to roll. I wanted to revisit Kurosawa’s film not because I felt like Living was lacking, but just because I adore that film to bits and pieces and was reminded of it again and again in Hermanus’ faithful-yet-independent adaptation. I found Living worthwhile, especially because it has its own reason for being made. Ikiru means “To Live”: a direct desire to make one’s life count and live on. Living is a bit more passive: it’s about rediscovering what it is that makes us fortunate, and I think this softer approach may resonate in these heated, uncertain times for those that want to ask the same questions but with less dread.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.