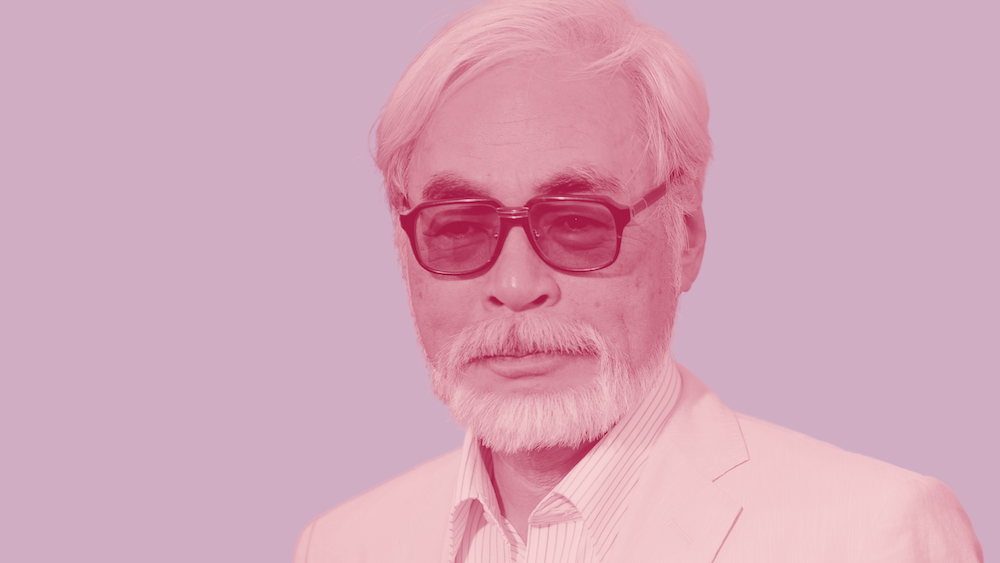

Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Hayao Miyazaki Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers who have made our Wall of Directors (and other greats)

I think it is safe to say that Japanese filmmaking icon Hayao Miyazaki is the greatest animation visionary of all time. It doesn’t even seem to be a hot take at this point. Co-founder of Studio Ghibli (one of the strongest animation studios) and director of numerous classics of the medium, Miyazaki has proven to be influential beyond just animated films. Directors who specialize in live-action features (like Steven Spielberg and James Cameron), video game developers (Shigeru Miyamoto and Hidemaro Fujibayashi with various entries in The Legend of Zelda series, particularly The Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom), and all kinds of artists from musicians to authors have expressed gratitude to the new world Miyazaki has granted them via his films. Miyazaki himself appears to be inspired by the familial tenderness of Yasujirō Ozu, the thrilling optimism of Spielberg, and the grand-scaled vitality of Akira Kurosawa.

It may be worth asking “What exactly has he done with his art?” before we proceed, as to best understand his impact (despite how clearly silly of a question this is). His approach to rule-breaking has never felt audacious or rebellious. Rather, Miyazaki treated storytelling as a series of experiments and the access to portals of new means that were previously untapped. This includes how meditative some of his films are, as we relax in the quiet and peaceful worlds of serenity in order to truly understand what it means to share these spaces with Miyazaki’s characters. Miyazaki’s affinity for the art of flight grants us both soaring freedom and breathtaking spectacle, depending on what the scenes call for. We mustn’t forget about how magnificently Miyazaki designs food in his films, with at least one dish in each feature that is guaranteed to make you crave food in this instance. There seems to be a common ground with these fixations: Miyazaki’s lust for life.

Whether you’re being whisked away to new worlds or faced with dealing with the problems within this one, Miyazaki always takes the time to make us appreciate what it means to be alive. He allows for breaths in between high-octane sequences so we remember to have life restored within us. We must know what calmness is in order to truly believe panic, surprise, or wonder. Miyazaki famously subscribed to the theory of creating storyboards before he pieced together a full screenplay for his films, allowing the art of his films to lead the way. Life itself is unpredictable, and he has captured that fleeting feeling of adventurous mystery through this tactic. Despite its unconventionality, Miyazaki has managed to resonate with audiences because he allows his heart to lead the way, not the over-calculations and reliance on conventions that one’s mind would lead to (and has done so time and time again). Miyazaki has also announced his intentions to retire time and time again, and yet he keeps coming back into the animation industry. Most would proclaim it’s due to his love of film and animation. I think it’s because this medium allows him to profess his adoration for being alive.

He grants us the same opportunity to re-experience the magic of being alive amidst life’s hardships, be they the fatalities of war, illness and dying, the ecological damage we’ve brought to our planet, or even big battles that children face that seem trivial to adults (like one’s first big move, or trying to face the perils of being a teenager). Miyazaki never speaks down to his audiences, no matter who his films are intended for. Additionally, every single one of his features brings us to a new world either right at the start of these stories or towards the climax after extensive buildups; no matter when we arrive at these wonderlands, we are spellbound every single time. While we process what is going on in our lives, we experience tranquil escapism in Miyazaki’s masterworks; we get the best of both worlds of cinematic therapy where we are understood and also granted the opportunity to leave our problems behind. The best part of all of this is that every single new reality Miyazaki gives us feels unique from one another, so no film feels similar to another outside of having his artistic thumbprint all over it.

I don’t think he has made a single bad film, but there are definitely some features that are weaker than others. In that same breath, I also have my obvious favourites that may be shared by you. I can easily see any of his films being considered the best in the eyes of someone else depending on what type of cinema they are into or what kinds of lives they have led. Miyazaki’s films mean different things to different people. Ranking all of his features is a bit tricky, but I have tried my best to do so down below. I can see the order of things here changing as I grow older and understand his filmography with different eyes. I’ll likely get to his short films at some point in the future, and maybe all of the Studio Ghibli releases if I am feeling ambitious enough. For now, here are all of the feature films of Hayao Miyazaki ranked from worst to best.

12. Porco Rosso

I do like Porco Rosso, but it is also the weakest Miyazaki film to me. The symbolism here is more blatant than we usually get from this director (for instance, the use of a pig to represent fascist Italy is so on the snout), and the film is more interested in being fun, satirical, and goofy than it is profound; in that same breath, I understand why some may gravitate towards this film because it certainly feels different from other Miyazaki films. The director himself said he wasn’t proud of it, proclaiming that he shouldn’t have made “an adult film for children” when remarking on the tonal questionability of the film. Regardless of my griping, again, I still think this is a good film. I just don’t know if it’s a great one because I only get fun out of this film and not really much else. As I’ve already stated, I don’t think Miyazaki has made a single bad film, so even if you are mildly curious about Porco Rosso and think that you may dig it, I recommend you check it out (this film shouldn’t only be for the biggest Miyazaki fans).

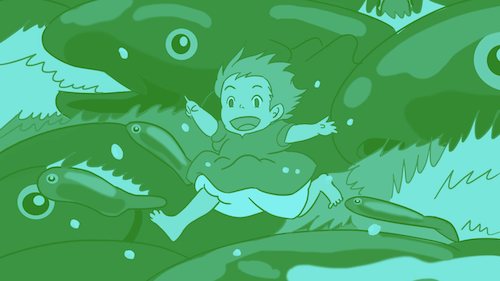

11. Ponyo

It may be a hot take to not have Ponyo dead last, but I also think that many Miyazaki obsessives may be missing the part where this is a film that is mostly meant for children. The film fixates on its cuteness and visual splendour more than anything, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it is bad. Is it flat? Perhaps, but the richness of the film can be found in the self-discovery that the protagonist children — the titular Ponyo, and Sōsuke — experience throughout the film, as our world converges with that of the ocean. Sure, this is The Little Mermaid whilst not being as good, but I still think Miyazaki brings something new here, from his take on water physics in animation (some jaw-dropping art comes out of this, by the way), a more subtle approach to the nature versus nurture debate, and some soothing, visual poetry that even children can find worthwhile (and not boring). Ponyo may not be changing the world anytime soon, but I also don’t think it deserves even three-quarters of the slander it continues to receive.

10. The Castle of Cagliostro

This Lupin the Third entry is clearly the least Miyazaki-like film in his entire filmography, but the fact that it is even remotely like the director’s signature style at all (which it is) means that it is even less like Monkey Punch’s Lupin III character and his tales. It isn’t as if Miyazaki didn’t know what he was doing, as he actually worked on the Lupin the Third Part I television series before he got into making feature films. I suppose he just saw this feature film, The Castle of Cagliostro, as his foray into becoming his own storyteller. In this film, the titular castle is the first of many entrances into the unknown that Miyazaki would become synonymous with, as Lupin III and his gang of thieves unlock an underground scheme that distributes counterfeit money worldwide. Going against the traits of a character he knows inside and out, Miyazaki grants Lupin III a conscious and the ability to change his heart and relinquish himself of misdeeds, much to the surprise of Inspector Zenigata and audiences worldwide. The Castle of Cagliostro is fun, exciting, and adventurous, but also not quite like anything in either Miyazaki or Lupin III’s respective filmographies. This is exactly what it seems like: Miyazaki’s bridge to his own new world. He would never look back.

9. Howl’s Moving Castle

There is much I love about Howl’s Moving Castle, but I also think that Miyazaki was trying many different gambles after the success of Spirited Away. The fact that we primarily focus on the character of Sophie and her experiences with aging as opposed to the titular wizard Howl feels like a bit of a misstep, as we are missing out on so much of the extraordinary events happening in the latter’s battle with his opposition. Outside of this reversal of protagonist and secondary character, the film feels a teensy bit overlong (an anomaly in Miyazaki’s filmography) and repetitive in ideas. Nonetheless, I think Howl’s Moving Castle’s take on global war as an answer to what was going on in Afghanistan and Iraq is profound. There’s a world in ruin and at odds with itself that Miyazaki was targeting here, and how quick life is (and the fact that we’re squandering our own lives by fighting whilst terminating the lives of others in the name of politics). Some of the imagination here is insurmountable, so I do understand why this film is a favourite for many. I also think that Miyazaki has pulled off much stronger films, regardless of how great Howl’s Moving Castle may be.

8. Kiki’s Delivery Service

Kiki’s Delivery Service may be quite simple when it comes to Miyazaki’s filmography, but I still think it is a highly effective coming-of-age motion picture. Instead of us entering a world that is different than ours, a witch enters our world and experiences a similar adjustment; really, this is Miyazaki’s way of having a child face teenhood and the real world ahead. As Kiki tries to find confidence within herself and manage the struggles of everyday life (be it relationships, health, or employment) in a small-but-apparent way, Miyazaki is giving younger audiences bite-sized morals that they can apply to their own lives. As Kiki begins to lose her witch powers over time, I understand this as a jaded teenager losing that youthful spark that Miyazaki doesn’t want any of us to lose (it’s clear that the animator never lost his throughout his life), and that is the most important takeaway here: never lose sight of what kept us going as wide-eyed, curious children. I feel like those that are quick to dismiss Kiki’s Delivery Service may be missing out on the very thing that allows them to enjoy so many other Miyazaki films: access to our younger selves.

7. Castle in the Sky

Now we get into the really good stuff. Castle in the Sky is the most glacial path to the world of the unknown in any Miyazaki film as it takes a good two-thirds to actually get to Laputa, but what a payoff there is once we reach the final act of the film (which is easily its best). The buildup to get there is a Spielbergian action-adventure via Pazu and Sheeta’s many escapes from the hideousness of our own world, but the startling arrival at Laputa is what really makes the film special: what they dreamt of is not what they arrive at. I hope not to ruffle any feathers by having this cult classic somewhat low on my list. Please believe me when I say that I really like Castle in the Sky and that this and the rest of this list are separated by mere molecules. What I will also say is that this is the first film in Miyazaki’s filmography to finally feel like the signature style we would all become greatly acquainted with, hence why I think many viewers hold it so close to their hearts. It’s true that he tapped into something unfound with Castle in the Sky. I also think that he would do so again and again, and in even better ways (without diminishing what he accomplishes with Castle in the Sky, mind you).

6. The Boy and the Heron

After a ten-year hiatus, Miyazaki returned with what was meant to be his umpteenth swansong (and yet he announced that he is open to working on yet another film…), and what a magnificent return that is. The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki’s most surreal film as he dives into the psyche of a grieving boy via a hostile, self-imploding wonderland akin to being Studio Ghibli’s version of Pixar’s Inside Out: the mending of a depressed, broken mind. At the same time, this feels like Miyazaki honouring The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time by infusing childlike wonder and humour with the darkness of reality (you’ll easily find some of Studio Ghibli’s grimmest images and concepts here) in the ultimate take on the coming-of-age transition. Whether Miyazaki is reviving his childhood past or facing the inevitability of death in his twilight years, The Boy and the Heron is deeply personal, riveting, and moving. It is a highly welcome return from a director of whom we thought we saw all the best before.

5. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Even though Nausicäa of the Valley of the Wind doesn’t feel completely like a typical Miyazaki film, it is for sure his first succinct idea since this is his debut stand-alone film after his Lipin III feature The Castle of Cagliostro. The other world we get here is a post-apocalyptic wasteland: an early and heavy reminder of what may happen if we don’t take care of our planet and each other. Rooted more in science fiction than Miyazaki has ever been since Nausicäa is a mature action film that finds value in our livelihoods and the planet as a whole. There’s a charming quality to the dated feel of the animation here, perhaps because Miyazaki was still kind of playing ball with what other anime films of the time may have looked and felt like, and yet this has Studio Ghibli's imagination all over it (despite predating the iconic studio). With the teenage title character having to face the tribulations and revelations ahead of her, global shifting, and breathtaking artistry and discovery, this is Miyazaki’s first classic through and through that is indicative of the themes and design that he would explore further and further from hereon out; he still nailed all of the above in this early attempt.

4. My Neighbor Totoro

Consider every entry from this point on perfect in my eyes. The greatest Miyazaki film intended for kids, My Neighbor Totoro takes the difficult concepts of moving to a new city, struggling with finances, and facing illness within the family with such warmth and nurturing qualities. What doesn’t get discussed enough is how much of the film is about the family dynamics of the Kusakabes as they embrace a challenging road ahead together, be it the patient father, the mature-for-her-age Satsuki, and the youngest child Mei who isn’t dealing with these changes all too well. The magical creatures including those adorable totoros and the amazing cat bus serve as last resorts to life’s problems in this film: you have to find the answers by searching deep within. That’s what Miyazaki has done here. He dove into the depths of his heart to find solace within the shifting tides of life in My Neighbor Totoro: a loving, adorable, spellbinding quest for familiarity within the unknown. Not many films bring the wide smile I get from this film. I love it so much.

3. The Wind Rises

What was meant to be a farewell to directing (we’ve heard this song and dance before and since, though) was Miyazaki’s way of getting in touch with his adoration for the art and science of flight in the best way he knew how: the medium of animation. Miyazaki tries his hand at making a loose biopic here by channelling the visions of engineer Jiro Horikoshi as he was tasked with making aircraft during the Second World War. While there are liberties taken here from historical rewrites to fantasy-based excursions (the "other world” we get here is in the dreams of Jiro), we are given a morality tale that showcases the conflict between self-perseverance and the hidden designs of the real world: our passions may turn into nightmares when handled by the motives of others. As Jiro strives for himself and the love of his life Nahoko, his brilliant mind regarding the science of aviation gets misused. All he ever wanted to do was to explore the extent of human-based flight. His genius, creativity, dreams, and regrets are all explored in The Wind Rises: a masterpiece of contemporary animation that doesn’t get discussed enough. It is a magnificent, beautiful, heartbreaking feature film that may get its proper dues someday.

2. Spirited Away

I’ll never forget the pivotal point Spirited Away had on animation when it dawned upon the twenty-first century. Even though it feels so much like Miyazaki’s style in most of his other films, this is the best film to be fully representative of his signature artistry. We get right into a new world — an abandoned city full of wandering spirits of the dead — as soon as the film starts and the expansive nature of this new reality for young Chihiro (as she faces the concepts of mortality, hard labour, systemic imbalance, and other sociopolitical themes) never eases up. Not many films get away with having their own fantasy-based rules whose only explanations are “because we can”, but Spirited Away feels endless with its magic and capabilities. Miyazaki gets us in touch with our childhoods, our spiritual sides, our acceptance of death, and the amusing and lovely things that make our miserable lives all worth fighting through. He brings life to the dead souls and aspects of society, turning our everyday mundanity into quests for us to conquer. Not many films revitalize you the way Spirited Away does as it nurtures our aching souls, empathizes with our working lives and struggles, and implores us to never stop dreaming.

1. Princess Mononoke

Miyazaki understands the gifts that Earth provides for us while we corrode and dismantle it in return, and he displays this toxic relationship in Princess Mononoke: one of the great fantasy epics of all time. While most Miyazaki films feel like they are for all ages, he takes this 1999 feature to a whole new level of maturity, perhaps to show where the medium of animation can go despite the stigma that it is a children’s art form (Princess Mononoke is anything but childish). Miyazaki reassembles our dying planet in his own creative ways via vegetational regrowth, biological titans, cancerous infections, and new species of animals that show where we can evolve if we don’t keep stunting Mother Nature. Equal parts tragic and titanic, Princess Mononoke channels your heart and soul as much as it presents the overwhelming repercussions of war, technology, and colonialism. It is only when we destroy ourselves (at this rate) that we will see nature grow again, this time through our ruins and ghosts. We must have a better relationship with the planet as Miyazaki begs of us to in Princess Mononoke: a film that features battles between humanity and nature, and humanity versus ourselves. It is an ambitious film artistically, thematically, socially, and cinematically. Princess Mononoke is a massive triumph of animation, fantasy, and contemporary cinema. In my opinion, it is also Hayao Miyazaki’s magnum opus whose impact continues to be felt to this day.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.