All of Us Strangers

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

By the time I was finished Andrew Haigh’s latest — and best — feature All of Us Strangers, I could feel how dry my eyes were after they were anything but. Without any over-explanations or complications within its duration, this film brought me to a place of acceptance and healing. I felt everything. I wasn’t told anything. Haigh has proven once again that he can extrapolate the indescribable feelings we are capable of as human beings and present them on the big screen. In All of Us Strangers, we have a candid diary of a lonely soul that is part Charlie Kaufman, part Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun (Paul Mescal included). We dip into not the mind or the heart of a man with no one else in his life; we gun straight for his soul to understand what faith keeps him going. We follow screenwriter Adam (played by Andrew Scott) through his latest case of writer’s block and come out of All of Us Strangers not with a finished idea (in the case of Adam, I mean) but a nourished spirit; his loneliness is our company. All of Us Strangers will break your heart and soothe your soul.

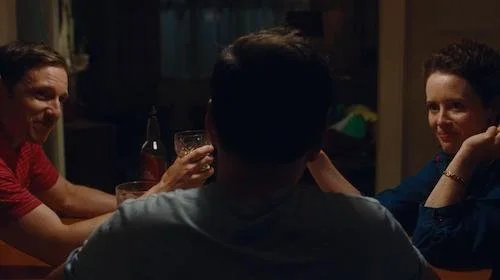

Adam lives alone in London and evacuates his condo during a fire alarm. Even during this routine procedure, there seems to be no one around him whatsoever. He spots a lone person still in his flat looking down upon him while all other condos — save for one (Adam’s own that he has left) — have their lights off. Once Adam goes back up post-test (so it wasn’t even a real fire alarm), his building neighbour Harry (Mescal) introduces himself to him. Finally: there’s someone in Adam’s life. It has been so long since Adam has had a lover that he has forgotten how to kiss properly. Meanwhile, Adam is trying to write a screenplay about his departed parents who died in a car accident when he was only twelve. As he is stuck on the very first line of his script, Adam revisits his old childhood stomping grounds for inspiration where he comes across his… father? Apparently, his parents are still around — perhaps in ghostly form — just as he remembers them back in the house he once lived in. They recognize him right away and are shocked at how much he has grown. He has the opportunity to bring his parents up to speed on his entire life and reconnect with the loved ones that he has missed for most of his life. In that same breath, they died during a very different time, and he is unsure how to share some of his personal traits, including his depression and his sexuality, yet he wants them to know everything about him at the same time. This is a chance to meet his parents again, and he wants to make the most of it.

All of Us Strangers combines grief and love into one inexplicable sensation that nurtures as much as it hurts.

As Adam ventures further into his past connection with his parent, he aims to establish his future with Harry, but really All of Us Strangers is meant to make us — and Adam — feel okay with the present. Part of me wonders if Haigh came up with this adaptation of Taichi Yamada’s novel Strangers during the pandemic when he was in isolation and in need of company. It reads like a story made by someone aching, trying to find comfort during a particularly harrowing time, and looking backward at who he once had daily communications with, be they the living of whom he cannot then-presently see, or the dead who will never return. Even if this wasn’t the case, Haigh has clearly lived through it all. He understands the agony of having lost loved ones and the hypothetical conversations we’d have with the dearly departed that we always run in our minds. He breaks down the life of a gay man through different eras and the varying situations and problems he would face (and still faces). He knows that, no matter who the lead character is, we all hurt in the same way. That sinking pit in your stomach — the same one that reminds you that you cannot find love and cannot speak to the dead ever again — is all throughout All of Us Strangers. It’s as if Adam is writing his screenplay as the film transpires and he settles for the emotions that pull us in every direction. We don’t see what Adam writes, because it doesn’t really feel possible to put these thoughts and feelings into words. On that note, I’d love to see how Haigh wrote All of Us Strangers; it almost feels paradoxical.

All of Us Strangers lingers in what feels like a phantasmagorical limbo, where all lives can coexist. At the same time, it isn’t that kind of an experience at all. It is strictly Adam’s: one that only features the minimum amount of faces (in fact, there are literally only six credited performances here). Who are these people of past and present, and what do they mean to Adam? We learn that he aches, but it’s almost as if he finds solace in this ache now. He is so existentially broken that he has found a home within the empty void of life. These are what these relationships mean to him, and Haigh presents these thoughts so exquisitely. Scott brings Adam to life with what is easily his best performance to date (okay, the best that isn’t a hot priest, I suppose). I sometimes find Scott to be too on-the-nose or effusive with his performances, but he couldn’t feel more real here. As the film goes on and Adam grapples with his circling visions, Scott brings tears of sadness and joy to a face that hasn’t expressed even a shred of hope in decades. This is an emotional euphoria for a broken man, and Scott absolutely owns it. Mescal, Claire Foy and Jamie Bell (the latter two play Adam’s parents) are tremendous supporting actors here who help bring out the most in Scott as an actor and Adam as a character. They’re all living vicariously through Adam, and they prove to be cathartic and beautiful.

All of Us Strangers takes you to the depths of Adam’s soul to face his grief and yearning.

All of Us Strangers made me feel like the child pretending to be an adult that I insist that I am every single day: I felt afraid and consoled at the same time. As someone who has experienced extreme grief for the first time this year, I felt like I was being talked to by my late mother. Even without that personal connection, I just know that Haigh’s interpretation of loss is startlingly exquisite and it will translate directly to even those who have been fortunate enough to not know what the death of a loved one feels like. Not once does All of Us Strangers feel like a religious take on coping with loss. If anything, it feels as neutrally natural as it can, even concluding with the stars in the sky replacing the notion of angels. You can attribute faith here if you’d like, but Haigh’s purpose here is much more universal: allowing us to know that we are all alone together in unison (we are each the stars in the sky, and their shine is our light at the end of the tunnel of darkness). The film carries on as if it is us in a daze: unable to differentiate between our awake states and our dreams, those present in our lives and the dead we try to still talk to. It knows what this ongoing purgatory of lamentation feels like, be it the weeping for the souls of others, the death of love, or our former selves that we can no longer ever recollect.

To watch All of Us Strangers is to experience cinematic exaltation: a sublime, poetic portrait of the agony of loneliness — be it through lovelessness, living in an unfamiliar city, or the cruel schism of people via death — that will both move you and haunt you. Not once does any bit of the film need to be explained or set up. It all just exists and allows us to understand it at our own pace as if the film itself is a ghost visiting us as a means of protection. We watch All of Us Strangers loud and clear, as it hears us. We see it as it sees us. Andrew Haigh creates a blanket of relief and yearning to wrap us up in during the anguishing, dark hours of the night so we can sleep tight and see another day. All of Us Strangers is a late-game changer in the already-stacked year of 2023 that will shake up your understanding of this year in film, the handle you have on your emotions, and how you perceive your isolation and grief. It is a monumental film that may be late to the party but is just as important to see as anything else this year; I insist that you do not miss out on the painfully gorgeous abreaction full of aesthetic and tonal richness known as All of Us Strangers, which is a feature that ascertains how united we are in how we are forsaken.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.