Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Alexander Payne Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers who have made our Wall of Directors (and other greats)

Some people are blessed with names that dictate how their lives would play out. When it comes to Constantine Alexander Payne, the Greek-American directing extraordinaire, his surname is homophonous with pain: the act of feeling anguish, agony, and discomfort. He has solidified himself as a master of tragic comedies throughout his multi-decade career, and he has projected sociopolitical themes and dilemmas through both satirical portraits of society and realistic, empathetic eulogies of those who are dead on the inside. All of his films make us laugh, and all of them make us cry. In fact, Payne has had one of the most steady careers in all of Hollywood with only one film out of his entire filmography being a dud of any sort (that film will unquestionably be ranked last here).

Otherwise, Payne has only made strong films. They either follow pitiful citizens of the world and allow us to wallow in their misfortunes, or present us with hyperboles of our own realities with caricatures of those we would otherwise hate (and yet we understand these characters as multifaceted beings here). Outside of one clear head-scratcher and an undeniable winner, every Payne film in between is great enough to make ranking his entire filmography quite difficult. It’s the kind of list where maybe I will feel quite differently down the road. For now, I feel pretty confident with how I have ranked these films. Let’s get started, because misery loves company. Here are all of the films by Alexander Payne ranked from worst to best.

9. Downsizing

While I appreciate Downsizing’s themes of environmental and sociopolitical footprints, the struggles of refugees, and the future’s obsession with minimalism, this is easily Payne’s career low point. Part of the problem is that we are presented with a fascinating reality outside of our own: one where people can be shrunken down to a teensy size for the rest of their lives, to reduce waste and other side effects of being a citizen of society; this leads to the disappointment that we barely even explore this concept, and at times I even forget that these people are “small”. Furthermore, Downsizing feels overlong, as though it runs in circles with its talking points, and it squanders both its creative potential and its acting talents (outside of a breakthrough performance from one Hong Chau who is the only actor here that can elevate herself above the material). Downsizing isn’t necessarily a bad film as there are still some major takeaways and ideas that I still think about (more to do with the film’s conversation on immigration and living conditions than the futuristic elements), but I can safely call this film mediocre and the sole miss in Payne’s entire cinematic career.

8. The Passion of Martin

I know The Passion of Martin is short enough to not be considered a feature film, but I follow the Academy’s rules which dictate that a film is a short if it is less than forty minutes. This film is forty-nine, so whether this is a feature or a featurette, it doesn’t matter. I’m including it anyway. It’s remarkable how ready Payne was to poke fun at the human experience in a film like this: one that questions the ethics of behaviour and the tug-of-war between animalistic instincts and progressive approaches handled by supposedly “evolved” creatures. As we follow the perverted and needy Martin, we see one-sided viewpoints on life via an unreliable narrator who wants to be loved in any capacity. Payne is perhaps his most cynical here as he depicts an insanely unlikeable protagonist and a world that isn’t ready to be his oyster; the ending feels like a Twilight Zone episode that somehow got rediscovered and preserved. While I would only advise that Payne fans check this film out, I still think The Passion of Martin is a good film made by a rising filmmaker who somehow already had a grasp of how shitty human beings can be. He would only go up — in quality, ambition, and even optimism — from here.

7. Citizen Ruth

Payne’s debut feature-length film (or second, if we’re going to continue splitting hairs), Citizen Ruth, feels more like a series of parody-based ideas than a cohesive narrative, and even then most of these ideas work. As Payne satirizes the debate between being pro-life and pro-choice (with both sides looking fairly awful; the irony of the pro-choice community forcing Ruth Stoops to fight for their side is quite strong), the film also presents us with an addict who is essentially impossible to save (the titular Ruth, played brilliantly by Laura Dern). If there is one argument that Citizen Ruth makes abundantly clear, it’s that both parties’ extremists only fight for themselves without actually caring about those who get caught in the middle. Case in point: Ruth is a mess and her life is never actually bettered nor her health improved or tended to, by those that promise to love her (for their own benefits). In a battle that swears that we care about livelihoods, there’s nothing more telling than the constantly-messy state of Ruth Stoops; Payne nailed it with this one, folks. He had the knack from the very start.

6. Nebraska

Nebraska is fairly straightforward by Payne’s standards, but even then there’s something curiously fascinating about the film’s approach to the concept of familial history. Even though we can be certain that the lottery ticket that Woody Grant possesses likely isn’t the million-dollar-winning miracle that he believes it is, the film instills the notion of fulfilling the journey to bring some sort of meaning to his and his family’s lives. Nebraska is full of disappointments within its narrative; the film is otherwise blemish-free as a touching dramedy that drives us to the heart of memory, misfortune, jadedness, and yearning. Sometimes we don’t get what we feel life owes us, but we can still try and make the most of it in our own quirky, meaningful ways. Nebraska is all about rewriting history (awful pasts, poor choices), even if on a small, self-nurturing scale.

5. About Schmidt

What looked like an acting vehicle for Jack Nicholson (who is, unsurprisingly, tremendous here as Warren R. Schmidt) was secretly a fuller dramedy experience by Payne and frequent collaborator Jim Taylor (screenwriter). While Election put Payne on the map, I believe it was About Schmidt that made him impossible to ignore, as the auteur rode the wave of an ongoing trend (with star-lead, introspective comedy dramas at the start of the twenty-first century) and set an extremely high bar right away. As Schmidt is en route to his daughter’s wedding, he still has never felt more alone despite the “promising” reunion. Payne tackles existentialism and isolation impeccably here. Even though Payne has films that have more going on conceptually, About Schmidt is Payne at his barest. There aren’t many frills or viewpoints here outside of the one statement that most of us can agree upon: just the act of being alive can be the most depressing thing imaginable. On the other hand, there’s always the possibility of finding happiness or purpose in the most unexpected places and times.

4. The Descendants

Where do we come from? How do we set up our children for success? Were the same steps taken for us? How do we hang on to what is rightfully ours from our family tree? The Descendants takes a startling approach to the concepts of familial history, tradition, and connectivity via two major, ongoing dilemmas: how to best handle a loved one being confined to life support, and how one should approach a shared, family trust. Matt King resides in Kaua’i, Hawaii (a clear indication of colonialism and the idea that his destiny was shaped, not there from the start of his life). His daughter seems to be out of hand, although she seems to have a stronger connection (albeit a negative one) with her mother than her own dad does; King’s wife is comatose and on the verge of death, yet he is learning more about her now than he did when they were both alive. As Payne takes us to an area usually associated with the concept of destination escapism, we are forced to reflect on our own predicaments in this wild ride known as life. One of his darkest comedies while also being arguably Payne’s heaviest film, The Descendants grapples with some heart-breaking topics with ease.

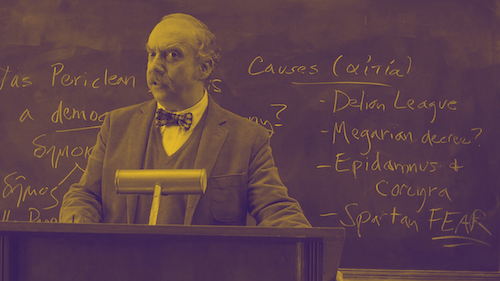

3. The Holdovers

Already beloved as a holiday staple, The Holdovers unites all viewers within the confinements of the Christmas season. It recognizes that everyone is susceptible to loneliness and a different outcome than what we expect from life. It also targets the small glimpses of love and care that we all share to varying degrees as three abandoned souls (one by bad luck, another by war-based death, and the last by an uncaring family) find solace in one another even when at their wit’s end. There’s no sugar-coating here: despite this being one of Payne’s more wholesome films (even this is a bit of a stretch as The Holdovers is still quite sad through and through), Payne will never lie to his audience about the state of things. Framed via a seventies New Hollywood aesthetic, we are reminded of a time when cinema was aiming to be as raw as ever. Here, Payne’s bittersweet take on the holiday season is our catharsis: we pity those in the film whilst feeling seen at the same time. The Holdovers is tender without being stupidly so, honest yet loving, and as warm as Payne may ever get (the film takes place in the heart of winter, and that’s all you need to know about Payne and his thresholds).

2. Election

Payne seemed to be more fascinated with recontextualizing reality than properly depicting it at the start of his career, and it felt like a promising path for him. Even though Citizen Ruth is a sensational debut feature film, maybe Payne felt like he already peaked with Election because he wouldn’t really take on a film quite like this again (outside of Downsizing, and even then his heart didn’t really seem to be in that film). It’s hard not to agree with Payne here because he instantly figured out how to best make an allegorical satire that both mocks and understands the idiocies of the modern age. As he recontextualizes the stupidity of the two-party political system in the United States (and the qualms of lobbyism, scandals, and the cluelessness of society’s youth) within the high school system, he displays assuredness right off the bat. Featuring a newcomer that was ready for superstardom (Reese Witherspoon), a former heartthrob playing against type as a slime-ball teacher (Matthew Broderick) and all the student body stereotypes in between, Election makes the frustrations of voting day feel like a hilarious ruse from another reality; upon further reflection, Election understands why we are constantly in states of peril no matter who is in power, and it almost feels like required viewing for both wide-eyed teenagers and exhausted adults.

1. Sideways

Something about Sideways felt instantly iconic. Perhaps it was the idea that almost everybody fell in love with a film about wine tasting when most people turn their noses (hah) to this very luxury of a pastime. The act of drunkenness is used in storytelling to lower the guards of characters and to reveal important, vulnerable information. In Sideways, we get exposed to the barest souls of four broken main characters, particularly Miles Raymond (Paul Giamatti) who feels completely unfulfilled in his life. This tour becomes a descent into insanity and self-loathing miasma: a sphere of chaos where the miseries of one latch onto other disgruntled individuals. We are left drowning in our sorrows (with Miles quite literally pouring wine over himself as an act of being baptized in the church of iniquity). Even if you don’t understand a lick of wine country culture, Sideways understands you. It understands all of us. In an era where the rise of social media had everyone projecting their best life online, Sideways reminded us that we are all unfortunate souls behind the scenes. While we don’t have to put these sides of us out there, we cannot forget that they exist. They make us human. Sideways was proof that Alexander Payne was a master of knowing what it means to be human, and if it wasn’t exemplified before, it was made certain at this very point. Sideways is one of the best films of the oughts, and it is Payne’s magnum opus.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.