The Last of Us: All the Right Qualities to Turn a Video Game into a Television Series

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

The secret’s out: HBO’s The Last of Us is a major success. It is already crowned one of the best visual medium adaptations of a video game of all time (then again, there’s not exactly a great track record in this department). In fact, I tried predicting that this would make a great film in an article from a few years ago. In hindsight, I don’t even know if my ideas translate as well as what actually transpired here. First of all, a series makes more sense than a stand alone film, and HBO already has that format set in stone (The Last of Us will allegedly go on for a number of seasons, with The Last of Us Part II being the premise of the second season). Secondly, I opted for an auteur (Alejandro G. Iñárritu was my pick), but The Last of Us got something far more fitting for its series structure. Naughty Dog’s co-president Neil Druckmann, who worked as a co-director and writer for the original game, co-created and co-write this series’ first season. Who is he partnered with? Craig Mazin, who you may recognize as the creator of the Chernobyl miniseries (which, quite frankly, is one of the best miniseries of all time). Chernobyl contains a number of crossover themes that feel quite relevant here, including the impending doom of the end of humanity, watching loved ones die and/or deteriorate, and the use of minimalism within a desolate world. This is a match made in heaven.

Everything seems to have lined up for The Last of Us, but I’d like to make the (obvious) point that this game seemed destined to have a strong adaptation from the start. I’ve grown up with Naughty Dog games for my entire life. I have been obsessed with Crash Bandicoot, particularly the sequel (Cortex Strikes Back) ever since I was a wide-eyed kid with a Playstation One. To this day, I play the original four Crash Bandicoot games, and being an even bigger lover of film has made me realize the early excellence of Naughty Dog’s expertise with showing and not telling. If we look at Cortex Strikes Back, I’ll skip the first level of the game (“Turtle Woods”) to speak about the second level, “Snow Go”. This is what you’re greeted with as soon as you start the game:

You are presented with three different crates right at the start of the level. Two of them have appeared in “Turtle Woods”: the Aku Aku crate in the middle with the mask (that grants you an extra hit from an enemy or obstacle), and the TNT crate on the right (which will explode and kill you if you attack it head-on, but bouncing off of the top will create a countdown that will detonate it three seconds later). So, what’s that green crate on the left? You don’t see it in “Turtle Woods”. In fact, it’s not in the very first Crash Bandicoot game at all. So you may feel incentivized to break it open, especially if you’re a child that doesn’t understand what nitroglycerine is. You hit the “NITRO” crate and die instantly before you can even spin or slide into it. It explodes upon impact. Now, that is a wake-up call. Even seven-year-old me understood to never touch that crate again. You restart the level on a new life, and make sure to instantly avoid that “NITRO” crate. This is only one example of how Naughty Dog relays new information to its players of all ages that makes sense and sticks with you, and this is before they even began to take storytelling seriously.

I could go through all of the original Crash Bandicoot games, or the Jak and Daxter series, or even Uncharted, which is where Naughty Dog really started to flex their narrative strengths (there is already a botched film adaptation of this series, mind you). For me, Uncharted is an immersive set of films you can play within, and this mindset would continue with the company’s magnum opus, The Last of Us. Being a Naughty Dog supporter for most of my life, I can connect the dots between this game and, well, Crash Bandicoot. The marsupial-based platformer forces you to go in one direction via a confined path, and The Last of Us technically coaches you exactly where to go as well (although it is much more deceiving about it). Clearly, Naughty Dog have a specific journey in mind that they want all players to experience. Maybe they were always meant to be linear storytellers. Additionally, the subtle little details of information that teach you about the game’s mechanics are also here and are even refined, feeling all the more natural and as though you have stumbled upon a discovery (instead of, say, a glowing, green crate right at the start of the level).

It’s easy to declare The Last of Us the most narratively driven project Naughty Dog have ever taken on (although Uncharted is extremely story driven as well), and the game actually feels cinematic for the majority of its playthrough (even right from the very start, where you play Sarah, Joel Miller’s daughter, wandering around in the middle of the night and noticing startling explosions causing the urgency to evacuate her home). The reason why The Last of Us is considered one of the greatest games of all time (it’s certainly in my top five) is because of how unforgettable the experience is. It feels quite similar to the spine-tingling moments of great films and series that make you forget about reality (except you are experiencing this sensation for hours on end and are in control of it). It’s time to dive into particulates as to why The Last of Us was destined to be a great film and/or series, with the knowledge that Naughty Dog are masters at linear gameplay.

The Story Is Near-Perfect

I learned an important lesson when I attended a lecture given by Darby McDevitt and Corey May on the writing of Assassin’s Creed video games. Writers for games have to keep two things in mind: the story the game wants you to experience, and the story you make for yourself. Programmed into most video games is a story that you are whisked away on with a beginning, middle, and end. There are characters, plot points, the crossing of thresholds, and all of the tropes of a narrative. Additionally, you can just run around, take in the scenery, commit whatever actions the games allow you to make, take as long as you want, and just have fun and do goofy things (sandbox games, like Rockstar Games’ Grand Theft Auto and Red Dead Redemption series, allow you to do as many things as possible and even question your own moral compass within these environments with varying degrees of consequences). You will create your own story within the game that literally no one else on Earth will be able to experience; even you won’t be able to recreate it exactly on the next playthrough.

Warning: the following stretch of this article includes minor spoilers to The Last of Us the video game, and this means that there are spoilers to the television series as well. Reader discretion is advised.

The story that Naughty Dog provides for us in The Last of Us is simple yet thorough. A Cordyceps fungus sparks a pandemic in 2013 that stops humanity in its tracks. Joel Miller tries to evacuate the city of Austin, Texas, with his daughter (Sarah) and younger brother. There has been a military response to the outbreak, and Joel and his family are cornered as they are mid escape. Sarah is murdered in Joel’s arms. We cut ahead to twenty years later and see how barren society is now. Most of the world has died. A significant portion of the human race has turned into various mutations from the Cordyceps fungal infection, and the different stages of this transmogrification (from runner, to clicker, to bloater, and whatever else in between) signify how much the virus has taken over the host body (as well as the likeliness of infection when one comes into contact with these people). The virus also drives the infected towards cannibalistic behaviours. Of the healthy population, you have various groups of people. There is a rebellion called the Fireflies that are searching for a proper cure to this sickness against the quarantine orders of the military, who are still vigilant and trigger-happy with their constrictive measures. There are people that kill other healthy beings to loot them and, well, survive via nourishment (some more cannibalism for you).

Then you have people that get by via smuggling, and that’s how Joel has survived. The game starts with his latest quest (once realizing that the weapons that were owed to him and his partner, Tess, have been sold to Fireflies): the smuggling of a teenager named Ellie. It is later discovered that Ellie is a special case: someone that has been bitten by one of the infected and didn’t transform. She could be the answer to the vaccine cure that can save humanity. Joel is disgruntled and jaded after the trauma that he has survived, and he treats the delivery of Ellie as a job at first; he is particularly cold towards her. Eventually, she becomes the daughter figure he missed and needed, and their bond is unbreakable. There are many other subplots as well, including the reunion between Joel and his brother Tommy, the efforts of survivalist Bill, the heartbreaking tale of Henry and his younger brother Sam that team up with Joel and Ellie, and even the lore of the Fireflies. I could spend an eternity going into all of this, but I recommend playing the game instead. It is also worth noting that there was no way that Naughty Dog could foretell how relevant The Last of Us would become years later as the world was torn via the spread of COVID-19, so the series will hit audiences a little differently. Then again, Craig Mazin depicted real horrors in Chernobyl, so his expertise will be especially fitting with how The Last of Us connects with our own experiences within a pandemic-plagued world.

The story that you can create yourself in the video game is full of so many discoveries. You stumble upon little artifacts (newspaper clippings, journal entries, and more), and these findings will build the mythology of The Last of Us even more than a simple play-through of the game. You can dig up little pendants of deceased Fireflies members and get familiar with all that have sacrificed their lives for the greater good of humanity. Ignoring the ephemera, you can take your time and look at the corpses, the debris, and all of the abandoned settings Naughty Dog has left for you. You can conjure up stories in your head as to who could have lived in these apartments, hotels, houses, and other domiciles. You can take note of the graffiti tags on so many buildings that were meant to be scriptures of caution (before society plummeted towards death). Or you can admire the nature that continues to grow as humanity dwindles, because that is a story in and of itself. You can do so much more with the little trinkets within the sensational world building of this game, and you will get different messages and ideas every time you play. There are also a myriad of easter eggs, but that’s a discussion for a different article that likely already exists online.

The Gameplay is Strongly Immersive

Naughty Dog have shown that they are great at storytelling in a number of ways, but The Last of Us is easily their biggest achievement when it comes to how attached you get to one of their games. The third-person perspective distances you from being completely immersed, but that’s really the only barricade you will find (if anything, I think the third-person point-of-view allows The Last of Us to transition seamlessly between cutscenes and gameplay, leaving you to pick up the pieces of the scene that just took place before you can take control of Joel again). Otherwise, The Last of Us invites you to put all of your energy and soul into its gameplay. You have to pay close attention to sounds, in case there are any clickers nearby that you don’t want to scare. You get more details from passersby if you eavesdrop (this is a testament, again, to the world building of the game, but also how invested you yourself have to be, as you ease closer to your television to hear what is being whispered around you).

There’s also something about the gameplay mechanics that leave you feeling like it is you running away from the infected, military, or bandits. Maybe it’s the crispness of the camera pans as you rotate your field-of-view, or how responsive your character is when you dart in any direction. It feels extremely fluid to the point of being almost completely natural. Not much about The Last of Us is actually scary in a horror-film sort of way outside of the infected beings and their behaviours, but I felt extremely tense playing the game often, as if my own life was on the line. The best films and series are ones that place us within the environment and we live vicariously through characters and sequences. The Last of Us as a game has a similar effect. Of course other video games are immersive (my personal favourite, The Legend of Zelda: The Breath of the Wild, is sublime in this way), but The Last of Us feels like an interactive series as opposed to a cinematic game, and part of that is the ability to make us feel like we are either acting in the production or actually living the horrors taking place.

Additionally, one of my favourite elements is how the game allows you to have your own approach. Do you want to be stealthy and savour your ammunition while you slowly take out enemies one-by-one without a trace? Or do you want to be Frank Reynolds of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia fame and go out guns blazing? I preferred the second approach, because the danger it posed (when enemies would spot me and try to take me out) was more thrilling and to my tastes. The thing is you have either option, and the game encourages both. Should you want to slink around like a shadow, you have objects you can toss (bricks and glass bottles) to make noise and distract your targets. If you are in a jam because you’re bitten off more than you can chew, Ellie — who is almost always by your side in this game — can “find” health packs and ammunition and bring it over to you.

Otherwise, you are encouraged to take either approach at times. You cannot barrel towards clickers (blind infected that have enhanced hearing), because they will find you and kill you in one shot. You kind of have to be aggressive towards bloaters (the strongest infected beings that require way too many shots and hits to kill), because they will destroy you if they’re even a foot near you (their reach is incredible). Should you increase the game difficulty, you’re almost forced to be more conservative as fights become harder and resources are fewer and farther between. Either way, you’re never really confined to one mindset or the other. I’ve charged towards clickers like a sprinting idiot. I’ve crept up on bloaters for surprise initial-strikes. The world is kind of your oyster in The Last of Us (outside of the fixed path you’re always invited to take). This allows the HBO series to dip into either mindset as it sees fit, and that’s liberating for an adaptation (it’s a guarantee that a showrunner doesn’t have to adhere to one tone at all times).

The Artistic merit is Tremendous

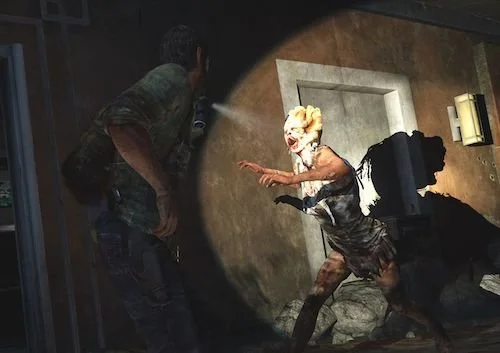

I’ve gone into the world building as a source of exposition, but there is a lot found within the actual design of The Last of Us that proves to be a great starting point for those that worked on the series. Those infected by Cordyceps alone are incredible to analyze. When first affected, people become host bodies for parasites that seemingly scream for help as their bodies change; Sam in the video game ponders if people are aware while they transition, or if their consciousness disappears (I personally believe that they are always aware). There are many minor details that showcase their anguish, and Naughty Dog was always trying to deliver this human quality (the fact that nu-metal band Otep’s Otep Shamaya was hired to make the female walkers’ screams is just perfect). Then the infected become clickers, and you can see a floral-like “blossom” come out of the faces of those that are changing (you can see the above image for an example); later in the game, it is learned that the fungus creeps into the brains of those that are sick, so it makes sense that the disfigurement will protrude from the heads and/or faces of the ill. The rest of their bodies also slowly mutate, and it feels like each clicker you meet has a different biological story. Finally, when one becomes a bloater, there is no recognition of a human being here: this is purely a mass of organs. The character design in the infected alone is so plentiful for the series to work with.

The world around the characters feels similar, with each and every “ruin” possessing its own aura. You can rummage through abandoned houses where flooring has collapsed, electronics were left plugged in (and are now beyond dead), and particular cracks or blemishes in walls and mirrors let you know vaguely what happened the night the world fell apart. I could go into all of the intricacies of how main characters are dressed, what scars they have, and then some, but this would take tomes. The thought that went into this game serves as its own portfolio of designs, storyboards, and more for HBO to work with. It’s another reason why this game is addictive for players: you will always notice new information even ten years later. Despite being a game that can be bulleted-through in a brief fifteen hours, it feels like you will never truly discover everything intentionally designed for the game to be as immersive as possible, even on an artistic level. One of my current favourite films, Annihilation, took many notes from this game and what it accomplished with its beautiful-yet-corroded world.

The Connection it Has With its Audience is Unbreakable

The final point is a minor one, and I’ve mentioned it many times already. There was always going to be an audience for any adaptation of The Last of Us. The viewership will be there. Money will be made. The question is whether or not this audience will be happy with what is made, but the devotion is there. People have connected with this game over the last ten years to the point of pure fluency and literacy of everything even related to the game. Sure. Other video games have their audiences, but there’s something about the lore of The Last of Us that resonates with players like a great film, novel, or, well, television series. The separate experiences we have are special to us individually. The story Naughty Dog gave us united us as a whole, as we got scared, persevered, and even shed some tears.

Whoever got to making an adaptation first was going to win this race of being noticed by the millions of fans of The Last of Us. It was all about making it well, and with the many different elements that I have laid out throughout this article, not only could there be a great adaption of this game (if all the right cards are played), it could be as immersive and affecting as the source material. Here we are. It’s the morning of the big reveal of the premiere. It seems as though this happened. It only felt impossible because of how bad most adaptions of video games are, but really it was quite feasible the entire time: The Last of Us deserves a great adaptation, and it could easily have one because of the ground work laid out in this highly-cinematic, immersive, narrative game. Well, it’s what we got. Enjoy The Last of Us on HBO, because I sure will.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.