Blonde

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: this reveal deals with sensitive topics of various forms of exploitation, as well as minor spoilers. Reader discretion is advised.

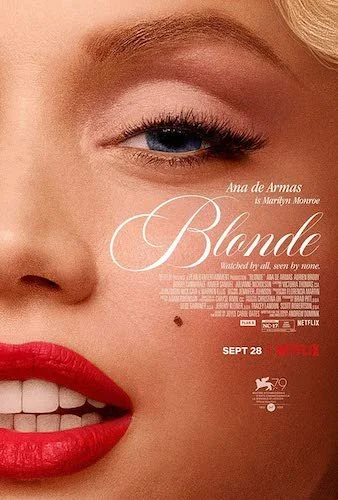

I will always celebrate when a celebrity biopic (or a fictional film based on a famous figure) is unconventional, because biographical films tend to be some of the most formulaic you can find. Unorthodoxy is exactly what you get with Andrew Dominik’s Blonde: his first feature since Killing Them Softly in 2012. In general, I find Domink to be the kind of filmmaker that always has great ideas but very little restraint, like the way The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford is a great film that still is burdened by being overlong and carried away. You won’t find this abnormality more present than in Blonde: the most conflicted I have been with a film in 2022 thus far. On one hand, I absolutely adore how adventurous this film is: it feels like Mother! mixed with a tell-all’s spillage of secrets (although Blonde is clearly not rooted in reality and is at least partially fictionalized). Then, there’s the hypocrisy this film faces, and this is the major reason why it didn’t resonate as much as it should have with me. Dominik adapted Joyce Carol Oates’ novel of the same name, but he clearly took some personal liberties here and misses the author’s gaze. We see the haunting of Monroe’s demons — how she was fetishized and abused in a myriad of ways — but Blonde also feels as guilty of this as the people the film is trying to expose.

We start off with Monroe as young Norma Jean Mortenson and her pitiless mother; her father is out of the picture, and the inquisitive Mortensen is met with an attack and an actual murder attempt from her mother, who showcases signs of mental instability. We quickly cut to an adult Mortenson who is already being harassed and used by Hollywood, and Blonde leaves nothing to your imagination. Eventually, she becomes Marilyn Monroe as a means of reinventing herself, but this backfires; now America is in love with an idolized version of herself that she has zero connection with, and she is still mistreated as a person. Her past, both identities, and her nightmares all converge into one holistic hell in Blonde, and it’s unlike anything you will see this year (for better or for worse). In ways, I was absolutely spellbound by the film, from Ana de Armas delivering her best work to date and completely sinking into this role (not only is she highly reminiscent of the late Monroe, but she also operates through all of the vulnerability of this part with hidden confidence and heaps of empathy that radiate off the screen) to the sublime photographical choices of Chayse Irvin (cutting from washed-out black and white images to other creative colourful shots, all with a square aspect ratio for most of the film).

Then, I was absolutely disgusted. Again, if the film is meant to connect us with the Norma Jean Mortensen/Marilyn Monroe that was preyed upon by the perversions of pop culture, then why does it exhibit the exact same gaze that has marred her image for decades? Not all of Blonde feels like it is sexualizing Monroe, but enough of it does that it feels wrong. Really wrong. Furthermore, if we are trying to humanize this person and expunge all of the stigmas surrounding her, why is she still framed as hopeless and naive throughout the film, particularly when the film weaves through her visions and reality (examples being her pining for her father through her numerous husbands)? Is this film trying to set the record straight of how poorly Monroe was treated through a challenging experience, or does Dominik like to indulge in shocks because he’s more entertained by this? For a film that’s aiming to be the catharsis of one of culture’s most exploited figures, Blonde certainly does some of its own exploiting.

You can see this dichotomy between panache and repulsive decision making in a nearly case-by-case pattern. When Monroe starts recalling the Hollywood Hills fire from her childhood all around her as an adult, Blonde has me hypnotized. When you’re viewing her memories of having miscarriages through the perspective of her vaginal canal, peering out at the doctors as they pry it open, I can’t help but find this completely unnecessary; Dominik is trying to say something here, but I don’t know what exactly it is, nor does it feel relevant. Monroe’s attachment to her stuffed tiger throughout her entire life? Heartbreaking. Monroe having to be shamed again and again without any ounce of cinematic warmth? Sadistic. You can go through each choice (and there are many here) and see what works for you and what doesn’t. Considering this is a nearly three hour film, Blonde really starts to drag the more misses you come across (although the hits — and the promise of more artistic choices that work — do help). I can’t help but think that some trimming (to save time and to get rid of some of the more problematic portions) would have benefited Blonde, but Dominik is almost as guilty as the many that the film points its finger at; he meant well to honour Monroe’s legacy, but he got carried away with his fixation of her to the point of sickness.

Then there is part of me that couldn’t look away from this film, even with all of its worst qualities in mind. De Armas is uncanny and the clear focal point of the acting here (no one comes close because they aren’t prioritized enough to leave an impact, although Julianne Nicholson as mother Gladys Pearl Baker and Bobby Cannavale as [presumably] Joe DiMaggio do a good job with the little time they get). Nick Cave and Warren Ellis’ score — heavily reminiscent of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ highly emotional album Ghosteen — cuts right to my soul, and is the only spirit found at all in this torture fest of a film. At times, Blonde feels like David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me: the exhibition of a worshipped female who is battered by desire, toxic masculinity, expectations, and self destruction. The difference is that Lynch’s film is at least a little understanding of its subject, Laura Palmer, to the point of providing safe spaces for her occasionally. Blonde is relentless. Parts of the film are some of the most riveting of the year, and I wish I could say more about the film in a positive light. However, it’s tough when a film is this mean spirited. Nearly three hours of pure torture. Even if done so in an artistic way, Blonde is just too much agony without any consoling of its focal point: a woman that dearly needed more authentic love than she ever got. Do we see the anguish Marilyn Monroe faced in Blonde? We absolutely do. Will we finally get closure for the late star that was forever misunderstood? No. Blonde is great at placing us in her shoes in her times of hurt, but it is quite awful at bringing her to life in any other way.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.