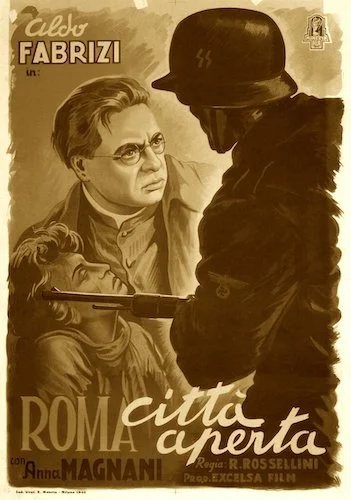

Rome, Open City

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. This is a Grand Prix winner: what the Palme d’Or was originally called before 1955. Rome, Open City won for the 1946 festival and was tied with ten other films.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Georges Huisman.

Jury: Iris Barry, Beaulieu, Antonin Brousil, J.H.J. De Jong, Don Tudor, Samuel Findlater, Sergei Gerasimov, Jan Korngold, Domingos Mascarenhas, Hugo Mauerhofer, Filippo Mennini, Moltke-Hansen, Fernand Rigot, Kjell Stromberg, Rodolfo Usigli, Youssef Wahby, Helge Wamberg.

Italian neorealism was a window into the world of the lower classes of the nation. Non-professional performers were used to get the most authentic depictions of what society was feeling collectively. Not much in the way of embellishments could be found. Neorealism feels almost like documentary filmmaking at times, although there is still enough of a distance between the subjects and the auteur’s gaze. However, there is always an intention set for each neorealist film: a message being sent across with the use of film as a global conveyance. A number of war films won the Grand Prix during the first full Cannes Film Festival, and these were the different perspectives of the contending nations that wanted to get their messages seen and heard by the world. On the topic of Italian cinema, the nation’s winner this year — during the eleven-way tie — is Rome, Open City: Roberto Rossellini’s magnum opus. It is an expansion of what Italian neorealism could be, especially as a similar response to the biggest theme of the festival: how the world was recovering from World War II.

Rossellini used neorealism to share the grievances and agonies of the Italian public while the country was occupied by Nazi forces. It’s a larger scale for this style that usually zeroes in on particular citizens to see the doom of the world around them. In Rome, Open City, we get a nation-wide story that encompasses the lives of a few characters during this harrowing year. Together, there is a portrait of devastation. Rossellini shoots Italy as a loved one undergoing sickness: an infestation of death, malice, and hatred. All of the loving people of the country are either slaughtered or tortured. This is where Rossellini’s heart lies, and it’s withering away. Is the director capturing the devastation of Italy’s people? Absolutely, but this is a neorealist film that also takes into account the country that houses these civilians and how it itself is hurting too. There is heartbreak coursing through the veins of Rossellini’s motherland, and he wants to capture all of it.

Italy is its own character in Rome, Open City, and it is in agony just like its people.

The screenplay was a collaborated effort between Rossellini, Alberto Consiglio and Sergio Amidei (both of whom wrote the source material Stories of Yesteryear), and one very familiar name: Federico Fellini. Together, the four writers pooled their frustrations and sadness into a love letter to Italy, which marked every single emotion felt since 1939. Furthermore, this screenplay made its way to the Academy Awards, where it was nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay (a major achievement for an international film at the time). This is especially noteworthy because neorealism typically tells a smaller story that resonates emotionally. Again, this was something more ambitious, and every note mattered. Well, Rossellini and company managed to turn characters into souls, premises into histories, and events into poetry of nightmarish proportions.

There are so many storylines and characters that matter in Rome, Open City, that trying to go into each and every one of them in a more capsule-like review for this project won’t do them justice. However, I would love to spotlight the one character that steals the entire picture: Anna Magnani’s Pina. Pina’s short-yet-earth-shattering performance guts me every time I see it. Like the girl in the red coat in Schindler’s List, Pina is a perfectly realized character that embodies so much more than a single person’s story. If anything, Pina feels like Italy itself: a maternal, loving figure that resembles the nurturing of lives and endless hospitality, who unfortunately winds up symbolizing so much more than that as the film goes on. All of the inner-workings of Rome, Open City are engrossing, but this is the storyline that destroys me every time I see it.

Anna Magnani’s character Pina is a minor role in Rome, Open City, yet she winds up becoming one of the strongest symbolic characters in all of cinema.

Rome, Open City is incredibly multifaceted, Whether you’re following the efforts of the resistance, seeing civilians try to survive, or the political torturing that takes place, you’re seeing a side of Italy that Roberto Rossellini demanded the world sees. This is a film that is highly artistic and showcases the auteur’s capabilities as a filmmaker, sure, but there is something more important that he wants to get across. He wanted Italy to be heard. As a result, Italian neorealism catapulted to a whole new echelon of scale, and Rossellini’s capabilities of an artist weren’t in vain: they would wind up being a blueprint of the next wave of a movement. I know that Rome, Open City was one of eleven winners of the original Grand Prix, but it is undeniably the headlining best picture of the festival, as far as I’m concerned (outside of Brief Encounter, mind you: this is a two-way tie I can get behind). Cannes was looking for art, innovation, and social commentary as strengths of the films they wanted to celebrate. Rome, Open City is neorealist perfection. It was the bar set for a movement, a festival, and an entire country’s art.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.