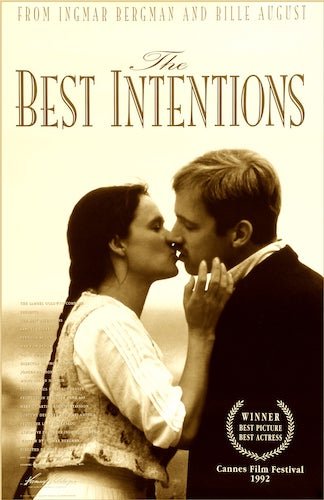

The Best Intentions

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. The Best Intentions won the thirty seventh Palme d’Or at the 1992 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Gérard Depardieu.

Jury: John Boorman, Carlo Di Palma, Jamie Lee Curtis, Joële Van Effenterre, Lester James Peries, Nana Djordjadze, Pedro Almodóvar, René Cleitman, Serge Toubiana.

Ingmar Bergman has almost always been critical of his father in his works, particularly how the paternal parish minister instilled strict religious values within their household. Ingmar Bergman himself has been at a loss of how he feels about Christianity for the majority of his career. The semi-autobiographical Fanny and Alexander was the last major hurrah for Bergman, and this five hour epic is as vicious about his disdain for forceful teachings as anything he’s ever done before. While he made projects after Fanny and Alexander, Bergman was essentially hanging up the director chair for good. He would return to old tales and ideas, but Fanny and Alexander was the last project he would put everything of himself into. Even still, he wrote the screenplay for The Best Intentions: another semi-factual story, this time the recollection of how his parents, Erik Bergman and Karin Åkerblom, met and fell in love, as well as their struggles they had to face. After being completely astounded by Billie August’s Pelle the Conqueror (a film he reportedly watched many times), Bergman passed off his screenplay to the Danish director. This was meant to be a more sympathetic look at Bergman’s father, but maybe that would translate best in the hands of another: away from Bergman whose constant resentment would maybe appear.

The end result is The Best Intentions: possibly the longest Palme d’Or winner in history (if you watch the miniseries version, which is superior to the three hour film version). At over five hours, The Best Intentions is a bit of an undertaking, but it is painfully beautiful. August’s subdued filmmaking allows the film to kind of exist without ever rubbing your face into the goings-on on screen, but Bergman’s writing lives through each and every shot. August directed The Best Intentions, but this is still a Bergman feature through and through just because of how loudly his pulse beats through everything we see and hear. His parents’ names are changed to Henrik and Anna, although the Bergman last name lives on. In the miniseries format, you’ll see both separate lives converge as one, and the Bergmans come into form as we have known them for the entirety of their son’s filmic career, but there is far more understanding here: either as a sign of forgiveness from Ingmar Bergman, or as his own apology for his earlier statements. There’s a stillness throughout The Best Intentions that somehow makes the entire picture far more interesting: as if its suspended animation of life — despite its continued progressions — is more riveting than seeing the same old song and dance of aging.

The Best Intentions is a touching film created by a conflicted son and through the lens of an outlier.

With all of this said, I may prefer The Best Intentions to Pelle the Conqueror, but the latter film is more dynamic and memorable. I just love how The Best Intentions made me feel. I could see myself falling in love, facing obstacles, and feeling life just zip past me like I have lived in my formative adult years, and August’s touching direction is the finishing touch on Bergman’s writing that allows this (Bergman is a colder director, let’s face it). I’m not sure how memorable the film is outside of remembering how I felt watching it: touched, saddened, and seen. Admittedly, I would say that the biggest reason to watch The Best Intentions is if you are a fan of Ingmar Bergman. It holds far less weight if you don’t care about the context and just want to see a romantic drama. Going into The Best Intentions with, well, the best intentions, will have you prepared for something far more monumental: seeing the trajectory of lives that would eventually lead to the birth of one of film’s greatest minds. The tenderness and care of the film make this time capsule a real treat to watch, especially if you know why it’s being made. It will feel fairly standard otherwise. Luckily, the Cannes jury knew what The Best Intentions is all about: living vicariously through memory, heritage, and healing.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.