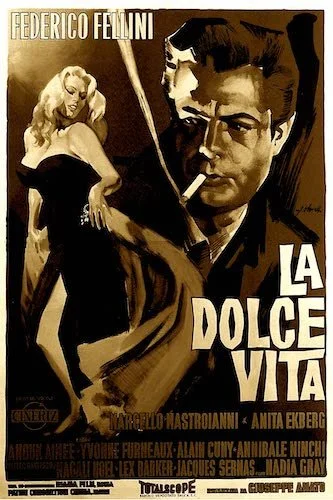

La Dolce Vita

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. La Dolce Vita won the sixth Palme d’Or at the 1960 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Georges Simenon.

Jury: Marc Allégret, Louis Chauvet, Diego Fabbri, Hidemi Ima, Grigori Kozintsev, Maurice Leroux, Max Lippmann, Henry Miller, Simone Renant, Ullises Petit de Murat.

I’ve written about La Dolce Vita before on Films Fatale, but now I’m covering the masterpiece in the context of the Palme d’Or. So 8 1/2 is Federico Fellini’s magnum opus to me, but something I’ve had to realize during my Palme d’Or project (where I review every single winner) is that the Cannes audiences and juries were blessed to see these classics upon release, and that I can only ever look at these films in hindsight. Do I slightly prefer 8 1/2? Yes, but La Dolce Vita is perfect cinema in its own way. Regardless, can you imagine being able to watch something this ambitious, prestigious, and affecting before the rest of the world knew it was coming to theatres later that year? That would feel like a magnificent secret: not only is Fellini back, but he’s better than ever (at the time, anyway). I keep bringing up 8 1/2, but I want to make something clear. That film was the result of Fellini not knowing what film to make next, so he reflected upon himself and his writer’s block. If we’re looking at the best film Fellini made that was not only his signature style but was him working with his utmost confidence in his prime, that film would have to be La Dolce Vita: a series of slices-of-life that actually feel close to impossible to break down.

I know I’ve written about La Dolce Vita before, but it feels so difficult to describe this film in any capacity, which seems like it would be frustrating for a critic, but it’s actually kind of refreshing at the same time. What even is La Dolce Vita? You can call it a film of vignettes, sure; a fashionable depiction of the high life of Italy; an engrossing affair that occasionally distances you as postmodern cinema; an exposition of an auteur that wanted to place everything he was capable of into three hours. Other Palme d’Or winners feel like they can be justified upon further explanation (perhaps they were shot well, they had something powerful to say, or there was some real artistry going on). Watching La Dolce Vita feels like a dumbfounding experience. If I was a jury member, I’d have been at a loss for words. My brain would go into autopilot mode and would just pass the golden leaf trophy to Fellini without even having to say anything. There are many films that you feel affected by when you leave the theatre, but not many films will leave you nonplussed like La Dolce Vita.

La Dolce Vita is equal parts allegorical and literal, blending the two elements together to make a fantastical experience.

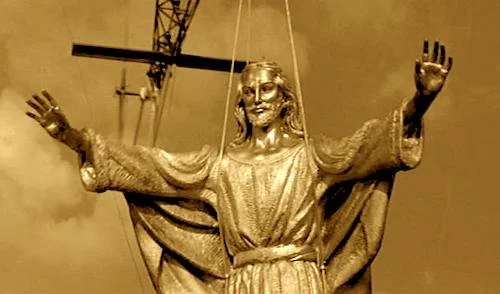

What makes La Dolce Vita so brilliant? I feel like it is unhinged and unaffected by any cinematic rules, but it feels far from anarchistic. Here is a film that goes about its own business and ways that is still made by a master of the medium that knows exactly what is needed. We begin the film with the iconic shot of the Jesus Christ statue being hoisted above parts of Italy via helicopter. What does it mean? Is Jesus overlooking the people of Rome? Are we supposed to be the Godly presence that peers over the numerous narrative episodes? Is it just something that Fellini thought looked nice? It’s highly interpretational, but it also has me hooked from the very beginning. It means something, sure, but it also is just mesmerizing to watch; what feels like the climax of another picture is presented here as a severed part (a “prologue”, if you will) that preludes the breathtaking filmmaking that is to come.

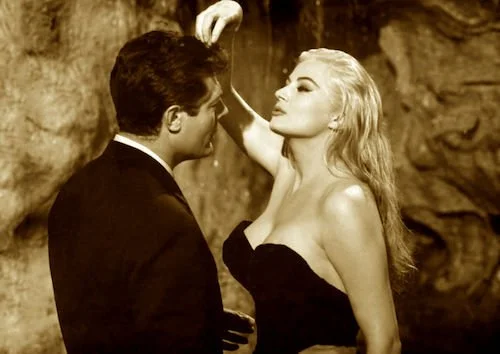

What comes next are a number of episodes that are all loosely connected by the character of Marcello Rubini: a paparazzo that goes from the outsider that tries to capture the upper classes of Italy to being a member of the exclusive club. The seven episodes (which may take place over the course of a week) encapsulate what Rubini (played by Marcello Mastroianni) experiences as the outlier that is now inhabiting that of which he wished to project. Some of his adventures are more literal, like the indulging of rich treats and celebrations. Some are inexplicable, including the discovery of an unusual, beached sea creature to wrap up the film: a cast-out member of a society that is left to die after having lived the good life. I find that La Dolce Vita invites you to pick out what you take away from each sequence, and a good example is the iconic Trevi Fountain scene. Is this a baptism into the life of fortune? Is it a depiction of wealth and that power means you can do as you please, even in the face of a public monument? Is this the display of a fleeting excitement that only such an act could portray? How do you feel about it? I find that any viewer would feel differently about each part.

The iconic Trevi Fountain sequence remains one of cinema’s most referenced, discussed moments because of its impressionable quality.

Another reason why La Dolce Vita is difficult to review is because of this last point: it’s one of those filmic experiences where it is best if you come up with your own conclusions. It is a three hour affair, but I could have watched it go on for another six. There’s something about the endlessness of La Dolce Vita that I never want to leave, and maybe it’s exactly what the lead character was desiring for us. We’ve had a taste of the high life, and now we wish to live within it. Fellini doesn’t get side tracked by reality, however, as his slightly (ever so slightly) surreal flourishes in La Dolce Vita render the film a dream and not a condescending session (that laughs at us for not being able to obtain these lifestyles). No. We get to be a part of La Dolce Vita. On the other hand, the film doesn’t get carried away with its imagination, and so we authentically feel like we’re amidst the aristocrats and their luxuries. This blending of creative liberties and fortunate living makes for an experience of splendour. Fellini has created films for the unfortunate before, and this was his way of channeling those who had the easy life. Even then, he never forgets that existentialism and the dreads of death (or the party ending, either for the guest that has to leave, the wealthy losing it all, or the lucky having to actually pass) which are sprinkled over the film. We know why we enjoy what we enjoy, especially because we are living in the now. What is the now? That’s for you to decide, even when the film places its own version in front of you.

La Dolce Vita is a film for cinephiles, art aficionados, and those that want to get wrapped up in an escape. This is my kind of excursion when it comes to cinema. I don’t need action, explosions, or high speed chases. I need an auteur to present mindsets and realms I’ve never seen or felt before, and will never experience quite the same way ever again. Again, just imagine what Cannes was feeling when they saw the premiere of this film. There’s no wonder why the jury voted unanimously in favour of this picture. It represents that feeling that cinephiles chase ever since they see that one film that makes them a lover of the medium: how do we feel like this again? La Dolce Vita is how: a film so sublime that it makes you fall in love with the craft, the storytelling, the art, and the milieu of cinema all over again every time you watch it.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.