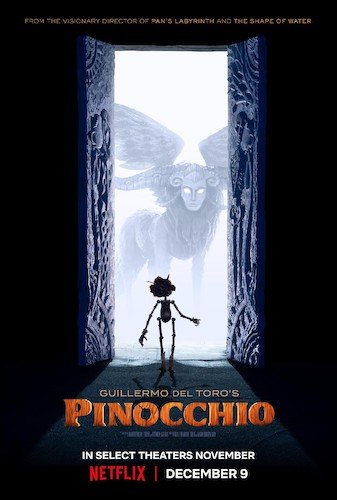

Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This trend of remaking (and remaking, and remaking, and remaking) Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio had better stop, because it’s pretty terrible for SEO maintenance. I’ve already covered one adaptation, will likely review the classic 1940 Disney version, and am now here presenting the latest adaptation (likely not the latest for long, but I’m three days behind its Netflix release, so for now that’s the case); not to mention the piece I wrote on 2022 having an astounding three versions of the same story. Well, let’s ignore every other version that exists for now, because it pleases me to say that Guillermo del Toro’s passion project is easily one of the most refreshing takes I’ve ever seen. For once, it didn’t feel like the same old song and dance. There is enough creativity here to justify this vision existing. Del Toro teamed up with stop-motion-animation visionary Mark Gustafson for this latest feature, and it’s a match made in heaven. Del Toro’s affinity for relating to misfits blends in perfectly with Gustafson’s stop motion perfectionism (also, the latter’s brush with darkness in works like Return to Oz helps; he also has very little to do with this particular moment in The Adventures of Mark Twain, but I’d like to think that he kept something from this project with him and used it as inspiration with Pinocchio). The end result is an imaginative, harrowing look at a story most of us are sick to death about hearing.

In this adaption, Geppetto is depressed after his son, Carlo (his name stemming from an obvious source), dies during the remnants of an aerial bombing during World War I. Geppetto is crushed for decades, slacks on his carpentry projects, and succumbs to alcoholism. In a fit of rage (not inspiration, like so many other versions of Pinocchio), he tries to defy God’s lack of empathy by recreating his son out of the wood that came from the pine tree that grew over Carlo’s grave. A blue Wood Sprite animates the wooden sculpture, which is shoddily assembled with nails sticking out and lopsided limbs, and it becomes sentient. Geppetto isn’t pleasantly surprised the next morning: he is horrified, and commands the being — now named Pinocchio (christened by the Wood Sprite) — to stay at home while he goes to church and repents his sins amidst the worst hangover of his life. It is shortly after this moment where Pinocchio disobeys and then spots his father’s broken sculpture of a crucified Jesus Christ. He wonders out loud why everyone loves this wooden boy, but not himself, who is treated like a freak of nature. His father has a quick retort: people have grown to know and love Jesus for centuries, but no one knows Pinocchio just yet. There’s something beautifully moving here that del Toro is trying to get at: not that Pinocchio will one day spark his own religion (although you never know in this day and age), but that Jesus Christ wasn’t always beloved. He was tortured and executed, and it took his death — and hundreds of years — for his legacy to be cherished by Christians.

Unfortunately, people attack those they do not know, and that’s a theme that is present in virtually every del Toro feature. It is especially evident here in Pinocchio, and this rings true once you consider the time that this film takes place. No. We’re not back in 1800’s Italy. We’re in the middle of the rise of fascism, where any naysayers of Benito Mussolini could be killed on sight. Little boys are being brainwashed to hate “others”, and Pinocchio gets a whiff of this hate during his numerous journeys. He also spends time with puppeteer Count Volpe, who is clearly exploiting Pinocchio, but I won’t go too deeply into how, as to not spoil the film. Instead, I bring up the symbol of puppetry and how blatant it is in a picture full of political hypnotism and indoctrination. Del Toro isn’t afraid to dip into some uncomfortable territory here, as Pinocchio touches upon ethical blindness and misguided faith, but he also doesn’t go too far with this darkness either. There is quite a bit of comedic relief, particularly stemming from Ewan McGregor’s brilliant Sebastian J. Cricket. The film gets a teensy bit cartoony at times, which is the slightest bit distracting when the film is just so tangible and relatable for the most part, but it isn’t enough to bother me in any major way.

Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio is a refreshingly mature take on a story we’ve heard a thousand times before. We have yet to see it done quite like this.

Del Toro knows how to approach darkness correctly, and not once does Pinocchio feel try-hard or edgy (unlike, say, 2010’s Alice in Wonderland). It’s because del Toro has always sympathized with monsters and creatures. He paints Pinocchio here with the same love that he would show Dr. Frankenstein’s creation: not as an abomination, but with a hug to let him know that he is loved. Not to get too personal, but I’ve seen Guillermo del Toro give talks before in person (he frequently visits Toronto), and I’ll never forget him discuss how he feels as though misfits in film and literature have forever been misunderstood. They should be acknowledged, appreciated, and accepted for who they are, and not judged for being different. In a story where we are told to expect that Pinocchio will one day turn into a “real” boy, I adore that del Toro sticks to his guns and allows us to continue to fall in love with the wooden creation as he is. I can’t say much about the ending, even though most people who have ever lived in the twentieth and twenty first centuries know roughly how it goes, but there is no feeling of replacement or the “better” version of the boy that arrives. There’s only the character you grow to love, as he is meant to be. I can’t celebrate this bold choice enough.

Pinocchio is very upfront with darkness and mortality (oh, yeah, Pinocchio can die and come back to life in this version), and it continues del Toro’s quest to find truth within a story that was often used to distract from hardship (nothing here is just because of “magic” or “fantasy”, and everything we see is rooted in the life and times that Pinocchio is a part of). The character designs here are extraordinary, ranging from the gorgeously horrifying sprites of life and death to the villagers around Pinocchio (Pinocchio himself is splendidly crafted, and the way he appears tells such a story in every frame). Additionally, there are a few misfits and unloved characters in this film, and Pinocchio embraces them all (another garnish of unconditional warmth that del Toro provides). Everyone has a unique look to them, and yet they feel very real. All is clearly stop motion animation, and yet it feels like a spectacle that has come to life. Even the music, which is clearly very indicative of the genre, feels sincere; Alexandre Desplat does a great job at making youthful tunes that don’t feel condescending or false. Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio is such an honest — yet different — take on this story that I can only imagine it will experience longevity in the way that The Nightmare Before Christmas has: with an audience that feels seen — and taken seriously — by this picture. Expect this version of Pinocchio to be loved and talked about for years.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.