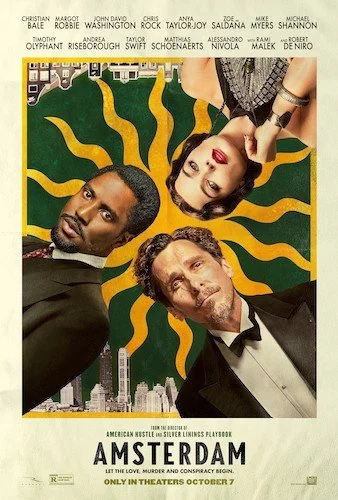

Amsterdam

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

I’ve always been on the fence with David O. Russell as a storyteller, because he definitely has strengths that he exercises in nearly every release he’s ever made. Quentin Tarantino has proclaimed him to be one of the best creators of cinematic characters of our time, and he’s not exactly wrong: O. Russell knows how to make unique souls that radiate off of the screen. He also has an authorial eye, but that acts as the bridge between the two sides of consistency that wind up affecting both his directing and his writing. Again, his characters are great, but they are linked to the hit-or-miss nature of O. Russell’s filmography: what his characters do. I’m aware that a lot of the dialogue and even the circumstances of his films happen in the moment, and he will base his plot around what he captures previously. That works rather well in explosive films like Silver Linings Playbook and The Fighter, but in a film like American Hustle — which is meant to be calculated and tightly knit — it can come off as unstable. Still, I like American Hustle: maybe not as much as I initially thought I did in a theatre full of electricity amongst an audience laughing exactly when O. Russell wanted them to, but enough to think it’s a good enough film. It just exposes the weakness in the director’s style.

With this in mind, we arrive at Amsterdam: his first film since 2015’s Joy, and you can see why this film took so long instantly. This is easily O. Russell’s most ambitious project in years (perhaps ever), and he put everything into this. He got Emmanuel Lubezki to make his depictions of 1910’s and 1930’s America (for the most part) pop with natural lighting, personal angles and gazes, and looming pans that make us feel like we are truly there. And what a great party to be a part of, with a superstar cast (led by brilliant performances by the three leads Christian Bale, John David Washington, and Margot Robbie, who bounce off of one another so naturally) that uphold the picture when it requires the assistance. Underneath it all — sublime sets, make-up, hairstyling, and costumes included — is Daniel Pemberton giving everything he’s got in his whimsical score (which turns into a bombastic march exactly when needed). Clearly, O. Russell wants everything to go right here, but it seems like he wishes this a little too much: his signature meandering gets in the way of the directness that this film should have had. While we get familiar with this world and its characters to the point that we feel like we know them personally, Amsterdam seems to just bumble along for at least an hour before it gets to the story it’s actually wanting to tell: a candid depiction of The Business Plot of 1933 (a conspiratorial means of replacing President Franklin D. Roosevelt with a corrupted leader to create a dictatorship in America). I feel like O. Russell was maybe commenting on how he views the political divide currently present in his come country and what he dreads will come next, but I could also be misreading his intentions here.

Even though Amsterdam steps on its own toes with its incessant storytelling methods, it is still quite dazzling in other ways, particularly with what we see in front of the camera (ranging from performances to sets).

Two World War I fighters, doctor Burt Berendsen (Bale) and lawyer Harold Woodsmann (Washington) develop a pact with nurse Valerie Voze (Robbie), the latter vet’s lover, to always stay together no matter what. They get separated after their dream life seems to be underway, and we flash forward to 1933. The film begins with an accident that gets pinned on Berendsen and Woodsmann, and we get the backstory afterwards (a questionable sequencing of events, if I’m honest). The accident involves the daughter of Senator Bill Meekins (who is originally aiding help from our two protagonists at first, before reneging and proclaiming that such help would end in disaster for all involved). She is proven right, as Berendsen and Woodsmann are instantly identified and given little wiggle room to prove their innocence. Their efforts have them winding up with Voze again, who is now living with her sister Libby (Anya Taylor-Joy) and brother Tom (Rami Malek). She is declared epileptic and unfit of taking care of herself, but Woodsmann and Berendsen see her differently; they have this pact, and they know something is wrong here, but it isn’t her. The trio of heroes make their way towards the bottom of this case: who did kill Senator Meekins, and who is trying to frame these upstanding individuals?

Amsterdam takes so much time fleshing its story out that it can definitely seem like a drag to some. For me, I am a patient viewer. If there is a good payoff, then I will judge what comes before in hindsight. I can definitely attest to how much Amsterdam dawdles, but I wouldn’t necessarily say that it ruins the film. It could have been a bigger wallop had it been refined, like (and I can’t believe I’m using this comparison, but it makes perfect sense) The Grand Budapest Hotel: another aesthetic, story-book-like depiction of wartime politics with a star studded cast that aimed to fire on all cylinders for Wes Anderson. Having said that, the payoff may not feel like the massive bombshell that O. Russell may have anticipated, but it is, once again, his characters — of whom we are now incredibly invested in (one hopes) — that we are transfixed by. The plot happens, and it does so passively. How the characters respond and recuperate is what makes Amsterdam tick the most.

I can easily see why this film would bore or frustrate viewers, but I was actually a little glued to the screen the entire duration. Had the final act been atrocious, sure. I would have been furious. However, there is some of O. Russell’s most beautiful revelations (outside of the one somewhat awkward aside used comedically that adds little to the climax of the film; you’ll know what I mean when you get there) to wrap up this experiment, and it is with these moments that I feel like Amsterdam is actually a reasonable watch (or even quite good at times). I don’t think its lulls tank the picture, but I could have done without them for sure (and Amsterdam would have been better off). It’s a shame to see what could have been a definitive film of the year weighed down by an auteur getting carried away, but I also love seeing Amsterdam work when it does so. It’s flawed, but maybe that gives the film an extra je ne sais quoi. I would have preferred the masterpiece that is partially buried here by unhinged tendencies, but I’ll take a fairly good film over a terrible one as well.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.