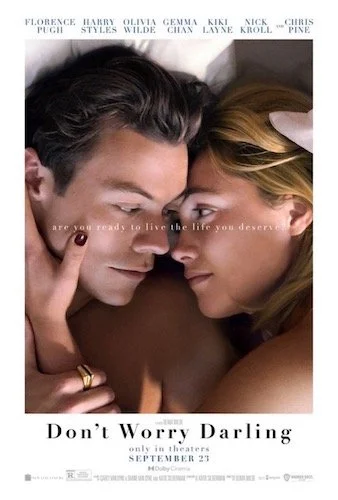

Don't Worry Darling

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Now that that dust has settled…

Olivia Wilde’s Don’t Worry Darling is a film I was looking forward to after I was quite pleased with her comedy drama Booksmart, particularly with how much attention the performer-turned-director put into her creative choices (especially in a film as silly and juvenile as this one). If she cared this much to make her film pop when she was directing a high school comedy, then what would a more serious effort look like? We got that answer sooner than we may have anticipated with Don’t Worry Darling: a psychological thriller that’s part Stepford Wives, part The Truman Show, part Black Swan (or would it be Perfect Blue?), and part The Twilight Zone. As you can see, it has many debatable inspirations, and it’s not that we can’t prove that Wilde was influenced by clear sources, it’s that there are so many that one might confuse what they may be. It’s easy to call Don’t Worry Darling yet another film of its kind with nothing new to discuss, but I also don’t think that’s necessarily true. Sure. Don’t Worry Darling has been done before, but Wilde has a few extra little details that make it matter right now. Furthermore, much of what happens in between these select moments and ideas — to me — feel like they would read even better on a second watch.

You can’t say that Wilde was lazy with this film. You can feel her efforts in virtually every single scene (hell, even every shot), and maybe that’s where you would draw the line (too much creator involvement), but I already stated that I like seeing what Wilde can do with a film, and so I personally felt intrigued by the countless creative and aesthetic choices she went with in this picture: everything adds to the intentional staginess, uneasiness, and clue placements that will have your brain racing (and perhaps solving Don’t Worry Darling quite early, but the film makes that actually a bit of a rewarding experience by allowing the world here to unravel in front of you once you figure everything out). Wilde also has a great team to make her many authorial inflections stick better, including Matthew Libatique behind the camera (this really matters in a film as visually concerned as this one), and all involved with the costumes and sets here. If you want to know what it feels like to live in a mannequin-like world, then here you go.

Alice lives the exact same life as her female neighbours in the company town of Victory. She lives with husband Jack, who departs for work at the same time as all of his male neighbours (like, down to the same second); their work is top secret and for the apparent betterment of the town of Victory. Alice doesn’t question anything at first, and why should she? Her husband is due for a promising promotion. She has a great group of friends. Every day is sunny and full of joy in Victory, California. Life couldn’t be simpler. However, this is not the case when Alice begins to put two-and-two together, realizing that life is actually far more complicated than she could have ever imagined. We the audience figure out that something is off within minutes, and Wilde wants the film to be this way; we’re not granted a single second of solace and comfort here.

Florence Pugh shines — like she always does — as Alice in Don’t Worry Darling: a considerable effort from second time director Olivia Wilde.

Florence Pugh is astounding as Alice, and we get all of the right notes from her performance; the uneasiness of her fictitious routines that feel normal to her; her slow realizations that something is amiss; her reactions to those that betray and let her down; her panic when she tries to break free from her constraints. The rest of the cast around her ranges from decent (Harry Styles as husband Jack, who occasionally feels out of his element next to his other polished costars, but he certainly does put in some work here to some success) to quite strong (Chris Pine as Frank, the founder and face of the Victory Project and the town it gestated), and everything solid in between (Wilde herself as neighbour Bunny, Gemma Chan as Frank’s wife, Shelley). However, it is Pugh that steals borderline every single scene and elevates the film from a series of interesting ideas into something you can follow from start to finish, no matter how much or how little you like the film.

I’ve brought up how I was satisfied with the amount of directorial ideas Wilde tossed at us (the creations of a pleasantly sterile environment, the uses of parallels and mirrors, and the like), and they aren’t new in the history of cinema, but they were done at just the right time and in such a way that feels urgent now: the statement that many that oppose progress wish to go back to a time where people, particularly women, had less control and power in the world and its numerous societies and industries. This is a blissful lie that was shared just to get by: that everything is okay, and we’re all happy because nothing is actively harming us. Wilde does get a bit heavy handed with these points, but I didn’t feel too bothered by this because I could feel her anger and frustration with how women and other marginalized communities continue to be gaslit, shunned, stunted, and ignored. This angle leads to the film’s twist that viewers will expect (maybe not the exact particulates, but a film as uncertain as Don’t Worry Darling obviously has something going on underneath it all).

Warning: Spoilers for Don’t Worry Darling are in this section of the review. Reader discretion is advised.

We eventually find out that Alice is the unwilling participant of the Victory Project as well: not the creation of a company town, but instead a simulated reality. She’s not living in some distant, undefined era from the past. It’s current day, and she is actually a highly qualified surgeon, whose lover Jack dwells at home and listens to toxic podcasts from Frank (yes, the same one that started the Victory Project, and you can figure out how Jack got involved from there). The majority of the men subject their partners — or strangers — to this experiment, where they play the lover that stays at home and keeps the house clean and the dinners ready to serve upon their husbands’ arrivals. Where do husbands go to work? In the real world. They drive to the portal of the simulation that wakes them up, so they can work outside of the simulation and keep the simulation going. Their partners are unaware of all of this, unless they are Margaret (who was perceived as crazy to keep the illusion alive), Alice (who endures the same torture), and Bunny (who hides her realization, so she can keep living with the children that she lost in the real world).

While I am fully on board with this idea, I do have to point out the couple of things that make this conclusion feel a teensy bit flimsy for me personally. What’s the significance of the red biplane, outside of leading Alice to the end of Victory’s perimeters? If everything in Victory is generated and/or a projection of some sort, why is this red biplane here? If Alice is imagining it, why does she share this with Margaret, whose child had a red plane toy? Also, Shelley’s change-of-heart with Frank is clearly a symbol of how women shouldn’t have to let men take the lead of everything and be submissive in toxic environments, but this doesn’t amount to anything else in Don’t Worry Darling’s conclusion, outside of the insinuation that Victory may now be in trouble and will experience a lot of change (which, if that’s the case, why can’t we see it?). Why does Alice see Frank as if he is a vision at times? How can Alice be going psychologically crazy if the world around her is rendered and she is an avatar of herself? I don’t suppose the world around her is rendered to make the “visions” or other phenomena, because that wouldn’t make sense. As for the abruptness of Alice waking up, I can live with this, because we also don’t get to see this snap back to reality in other similar works. We’re left wondering what comes next in the real world but we also know that Alice is now free, no matter what happens. Otherwise, these kinds of errors are truly the film’s biggest flaws: the kind that linger just as much as the stuff I do like, and hinder an otherwise pretty good film to the point of being impossible to ignore.

End Of Spoilers

Despite these few missteps, I feel like Don’t Worry Darling is pretty confident in most of its other statements, and rightfully so: there’s something important about this oft-told story being shared now. Looking fondly back at times of old without regarding their issues is a massive problem that we continuously face today, when bigots remark on the good old days while ignoring the misogyny, racism, and other forms of hate that came with them. Furthermore, the idea of escaping life as it is through ulterior means is one that has been discussed quite frequently nowadays, what with meta verses, NFT neighbourhoods, VR realms, and this ongoing idea that the world is a simulation. Blend these together, and you get a film that provides the issues in cleansing a world of its flaws by encouraging the problematic ways of old with the lack of addressing the real issues and solving them head on (all underneath implied power over women, when they still aren’t facing complete equality in 20-freaking-22). How isn’t what Olivia Wilde presents in Don’t Worry Darling at least a little fresh and contemporary? While the film occasionally clunks (some lines feel forced to get points across, as an additional concern I need to point out), Don’t Worry Darling is still engrossing enough that I felt like it worked more than it didn’t. I await what Wilde does next, and hope that she keeps up the spirit in her next project, whatever it may be. Hell, if she returns with an even better film, who knows what will come our way, if Don’t Worry Darling is flawed but still as entrancing as it is.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.