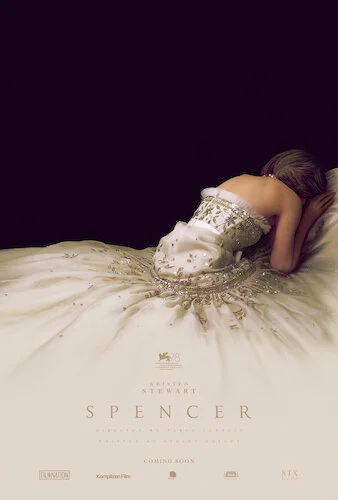

Spencer

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

If the character of Maggie in Pablo Larraín’s latest film Spencer has taught us anything, it’s that women have each others’ backs. In a cinematic sense, this is true with how Larraín’s magnum opus Jackie operates as a dive into the grief of Jackie Kennedy, whilst Spencer tries to crack open the private thoughts of one Princess Diana. Jackie conjures up its own discussions based on real events and horrors, but Spencer takes this historical revisionist approach a few steps further by being quite fictional entirely. All in all, both works are sister films to one another, and you get a greater sense of what Larraín’s intention is when he selects real women of notable families who have had to deal with the scrutiny of the public eye, the weight of rules bestowed upon them, and the inability to feel pain in their own private ways.

In a way that will bother most royalists, the Chilean filmmaker allows Spencer to be enough of a fabrication of Diana’s life — particularly around the time of public rumblings about her marriage with Prince Charles. What if Diana spotted him having an affair, and she bottled up this heartbreak and devastation, as to appeal to her in-laws, and remain composed to the masses? What if we could see the nightmares she conjured up in her head, as if she was slowly going delirious from pressure? What if Princess Diana could say anything? She does just that, as the very first line that the Princess of Wales utters in Spencer is “fucking hell” (I believe), while she is lost on her way to her Christmas weekend getaway with her family. Those of you that expect a safe film are instantly warned that you won’t get what you want. Already, Diana is frustrated and fighting to keep her composure. It’s only harder from here.

Kristen Stewart has never been better than she is as Princess Diana: a daunting role for anyone, let alone an actress who has had media scrutiny stacked up against her.

That unnerving welcome comes from Kristen Stewart, who plays Princess Diana. You can feel safe. From the trailer that barely revealed anything, as if the promotional material was disguising a bad performance from us, it seemed like curious future viewers were apprehensive about this casting choice. Stewart has never been better. A major reason why this film is rated as highly as it is is because she nails every single scene, carrying the entire film entirely on her back, and being in complete control of her performance (as to not overact or carry out an impersonation over a transformation). At times, it’s clearly Kristen Stewart on screen, but in a good way (like we’re seeing the height of her signature style here, which shames us for ever judging her in the way that other actors with recognizable traits are usually adored). Otherwise, Stewart is occasionally completely transformed as the Princess of Wales — albeit her dark side that she rarely showed. Diana’s graces pop in and out during this time of distress, but Stewart also provides a genuine mysteriousness to her, as well as an interpretation of her frustrated and depressed sides.

She leads us through Larraín’s nightmarish take on Diana’s troubled psyche since the majority of the other characters — real or fictitious — won’t help in any way. Outside of the not-real roles of Maggie (who acts as a friend and helper for Diana) and Equerry Major Gregory (as well as her children, Princes William, and Harry), everyone else exists just around her, either digging into her soul (through piercing glances or Charles’ savage tone) or acting as their own ornaments. I rarely state this, since I really don’t think it matters, but these characters barely resembling their real-life counterparts is distracting enough, mainly because they barely (or never) speak (outside of Prince Charles), so we can only reflect on who they are visually. Still, Stewart’s dynamic performance, as well as the many artistic and thematic achievements, pull us by these perplexing choices.

Spencer is a sensational film artistically.

The last time Larraïn had an English-language film, he worked with Mica Levi on a score for the ages. This time, he brought on board Jonny Greenwood of Radiohead fame (as well as the musical mastermind behind the scores for various films, including Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master, Phantom Thread, and Greenwood’s musical opus There Will Be Blood). We get the best of both worlds here, with Greenwood’s affinity for classical music swirling around you (literally at times, with the plinking and pattering of percussive or string sounds flittering around your head), as well as his knack for making you feel sick to your stomach (his eerie strings are back). This feels like the prestige surrounding Diana coming crashing down, as if we’re fighting to live a regal life whilst collapsing under the spotlight.

In the way that Greenwood’s score circles about, and Princess Diana suffers repetitive fates, Spencer is as cyclical as it is symbolic. We begin with a shot of a dead pheasant on the road, which predicts the shooting that Charles and the boys do later on in the film (as well as Diana’s acknowledgement that these birds are being brought up just to be killed for sport, much like many public figures). We also get the gist of Diana’s surroundings in other ways, like the obvious sign for the employees in the basement below that the entire building can hear anything that they do; the same is true for Diana, who can’t even mutter under her breath in a room alone without the world scorning her. One of my favourite metaphors is the snooker table when Diana and Charles exchange choice words. Here is a game where every move matters, and the slightest of mistakes will cause great penalties.

The hallucinations in Spencer are a disturbing look at the internal battles of someone who has to permanently save face.

Throughout Spencer, Diana is haunted by the metaphorical ghost of Queen Anne Boleyn, who was executed for treason, as if Diana felt like she had to tip toe every second of her life: it’s Prince Charles that was destroying the marriage, but surely it would be her that would be thrown to the wolves. These fears turn into hallucinations, which begin as scenes that will throw you off course, and plunge into full-on visions that transcend time and space. If Princess Diana has to endure her own battles internally, she can explore her own escapes just as vividly. It’s these experimental deviations from your traditional period piece biopic that help Spencer even more. We couldn’t care less about the people around her judging her. However, we want to know what she is experiencing, even if her darkest hours frighten us: thoughts of death, her struggles with bulimia, and the feeling of choking from that damned pearl necklace that’s now stained with adultery.

Hearing Princess Diana’s secret desires (even if they’re not real) makes us feel closer to the late icon than ever before. Knowing she just wants to have some fast food, enjoy life again, and be away from any royal position makes her mental and physical jail cells feel all the more suffocating. We never once see paparazzi, but we know they’re there, regardless if the curtains are shut or wide open. Even we invade her privacy by seeing shots of her showering (and in other vulnerable positions). These moments of insecurity amidst her dream sequences make us unsure of what is actually happening, and often times you may find yourself wrong. At the end of the day, Princess Diana just wanted to be happy, free, and with her sons, away from the hell she didn’t foresee. Pablo Larraín grants her this even briefly in Spencer, his latest triumph, but not before allowing us to experience her pain firsthand.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.