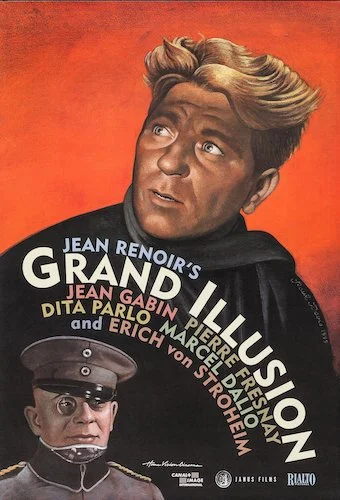

La Grande Illusion

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

For both Veterans Day and Remembrance Day, we’re going to look at one of the finest films about World War I: La grande illusion.

Warning: contains potential spoilers. Reader discretion is advised.

Jean Renoir came from artistic royalty as the son of impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir. It was only destiny that he would become the voice of his own generation via his craft. However, film wasn’t always considered art in its own right. If anything, it was even frowned upon as the entertainment form of circus patrons and the lower class, so to have it be the avenue of the son of an iconic painter isn’t quite as obvious as one may think. Of course, film was slowly being understood as the next platform for the biggest voices within artistic mediums once names like Charlie Chaplin, D. W. Griffith, Fritz Lang and the like began to grace the big screens with their advancements. It was only a matter of time for the descendant of high art to find that film possessed the same kind of interpretive power; perhaps in more of a poetic narrative sense with the way that Renoir told stories, but it’s there.

While Renoir would go on to make some of the best films in film history — especially of the ‘30s (with The Rules of the Game just around the corner) — his first of these opuses (and a definite contender for the conversation of his absolute masterpiece) is La grande illusion, cowritten by Charles Spaak and inspired by the writings of Norman Angell. The premise is simple: can prisoners of war escape what feels like an impenetrable fortress? Using World War I as a backdrop (possibly with the fear of what would become World War II in mind, and the knowledge of what could transpire at any moment), La grand illusion speaks from the perspective of a cynic that has seen far too much to know that maybe civilization is beyond repair. However, in the form of promising protagonists, La grande illusion aims to remind us of the smallest glimpses of hope within turmoil.

La grande illusion finds hope within darkness.

The film becomes a game rather quickly, with two POWs having to analyze their surroundings and spot the best ways to escape. Even this plot could have easily been told plainly as an adventure tale if handled by a director that was wanting to be a part of the early epics of the sound era. Instead, Renoir opts for a booming statement on the cyclical nature of history’s mistakes, especially when you look at the prison as this starting point that we keep resorting to. Humanity keeps falling into the same thought patterns and allowing its own capabilities of evil to take over. Think of it as this damnation we can’t leave, and that this escape plan is our efforts to resolve the curses of the civilization age.

It doesn’t feel like this could be Renoir’s mission statement until the bitter end, when even the slightest sign of a conclusion is left open ended. Did our protagonists manage to fulfill their hopes of freedom? I’d argue no, no matter what happens. Think of this. First, if these characters live, they could be forever on the run and having to look over their shoulders; their days as free individuals could be short, and if not, their lives could be forever marked with concern and anguish. There’s also the possibility that they could be caught again if they survive, and so they’re not any more free from the clutches of hell than they were initially. Finally, we can admit it: these protagonists may very well be dead, and this was their brush with a proper life. All in all, they are in their own prisons outside of the literal system that we see in the film.

La grande illusion is as metaphorical as it is literal.

If diving deeply isn’t your thing, have no fear. The beauty of the French art films of the ‘30s is that they hold as much literal nuance as they do heavy poetic symbolism. Even if you don’t want to analyze La grande illusion beyond its borders, you have a very tense and heart wrenching look at survival and hurt, told at a particularly appropriate time. Picture this: the world was feeling the after effects of the Great Depression, and there were clear signs of some more political turmoil coming (of course, this would bubble and turn into the second World War). As stated before, there is a clear awareness of what was to come, and it’s all over the pessimistic tone of the film, as it wallows in its own damage whilst the quest to escape continues. This only adds to the uncertainty of the film; something more upbeat and wholesome would likely have led you to believe that we’d get out of this thing okay.

In that sense, La grande illusion is so ahead of its time, particularly during a moment when Hollywood was only getting calmer (thanks to the Production Code’s limitations); it was clear proof that the cinema of the world would continue to search truths everywhere, and not just in the convenient comfort of a jaded industry. Renoir wasn’t selling you a product (again, he came from a home that taught interpretive truths within art), but instead allowing you a place to grieve, to wonder, and to marinate on what has happened, what could happen again, and the fractured sanity of those who choose to fight (within a system that banks off of their efforts in a whole myriad of ways). Renoir was taking shots at every kind of social entity here, with the idea that civilization was built improperly and that we will never get out of what has already been constructed. In 2021, I can’t help but still feel like he continues to be right. Even if we break out of these four walls, there’s the grand illusion that we have made it out, for it is the imaginary walls that continue to house us in (especially once our own guards are down).

La grande illusion’s depressing realism hits as hard as it needs to, even many decades later.

Jean Renoir would continue to be as hard hitting as he is here, except in so many starkly different ways. The Rules of the Game is biting satire. The Crime of Monsieur Lange is romanticized awareness. Boudu Saved from Drowning feels like the difficult grey area that we must pull out of. Partie de campagne finds the smallest ounce of pain within beauty. You can keep going with all of his films. He feels like he is bending and coaxing the deepest feelings of despair with La grande illusion, as if it is his most direct conversation of this sort. Outside of a morsel of an exit, there really is no hiding behind anything here, and it felt like Renoir was saying the most that he could to an audience that maybe forgot that they needed to hear this (with serenity being dangled in front of their faces by other outlets, with promise of a better world to come). La grande illusion is impeccably written in every way, it is hypnotic to watch, and it carries as big of a punch as it ever did. If Renoir is here to remind us that hope tends to the fires of illusion, at least he told us the truth in his own way, resulting in one of cinema’s most bittersweet opuses.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.