Lost: Perfect Reception

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This is an entry in our Perfect Reception series. Submit your favourite television series for review here!

WARNING: THERE ARE SPOILERS IN THIS RETROSPECTIVE PIECE ON LOST.

This month’s edition of Perfect Reception finds us looking at a show that could only have come out exactly when it did. Network television wasn’t courageous enough back in the ‘90s (look at how a station handled Twin Peaks, for instance). The 2010’s introduced the height of streaming, so the very fabric of television has been reshaped (series are made to be marathoned). Right in between these two bookends is the 2000’s: the optimal moment for a certain television show that capitalized on all of its benefits: time, place, and the unknown. It all started with Jeffrey Lieber, who pitched the series Nowhere (a Lord of the Flies for the new age, where survivors are stranded on an island) until it was finally picked up by ABC. Two major names were then attached to this project to help it really take off. J. J. Abrams is now associated with his connections to science fiction, but at this point he really was in a completely different ballpark with Felicity and Alias. Then there was Damon Lindelof, who now known is for his meta mind-bending works, also typically sci-fi; by 2004, he was wrapping up his work on Crossing Jordan (also not sci-fi).

Essentially, Nowhere became Lost once Abrams and Lindelof came on board, and Lieber’s vision — as history has told us — really wasn’t maintained whatsoever. Outside of the pilot episode, which possesses Lieber’s take on a plane crash that leaves the surviving passengers stuck on an island, Lieber would have virtually nothing to do with Lost. That would only be the first inexplicable element of the show, since, as we all know, the series would only become stranger and stranger. I’m not covering Lost because of the rules it played by, but rather because it remains one of the boldest shows in network history. Again, with the rise in power of subscription services and streaming, maybe there will never be another Lost: the crazier shows will be picked up by the companies that will allow them to have free reign, and networks will get by in their own way.

In order to continue, let’s look back at the pilot, which is quite possibly the best TV pilot of all time. Within seconds you’re drawn in: a massive scene of a destroyed airplane, the suffering passengers, and all of the sudden fatality that everyone is facing. The pilot only possesses a smidgen of the experimental nature that the rest of the series would quickly dip towards, but it still contains just as much mystery. Who are these people? What exactly happened? Where are they now? Will they survive? Because you’re gripped right away, you are invested enough to await whatever comes your way. What follows next is sensational television: a myriad of additional questions now that you’re paying attention, and a leap into the unknown (since you’d never watch a show like this without being hooked from the get go). Lost became the water cooler series of the 2000’s: everyone had to try and figure out what was going to happen, and we had to talk about what we thought we knew. Do these random numbers mean anything? Is any of this real? How do I stop being lost within Lost? That’s the beauty of the show’s name. At its most shallow, it means that people are lost on an island. Dig a bit deeper, and you’ll realize that it’s about being lost within humanity, on the moral compass, inside one’s own mind, and even in time and place (in a parallel dimension kind of way). Then there’s the final meaning: you yourself got to be lost in a way no other series at the time could make you for an hour every week. This was your escape.

Season one was the revelation of exposition. Here are all of these new names, and the barest of basics of their backgrounds. Jack Shephard is a medical wiz who can’t match the achievements of his recently departed father. Charlie Pace is a beloved rockstar struggling with addictions. Kate Austen is a fugitive: this was her chance to start a new life for good. Then, the revelations got a bit stranger. John Locke is paralyzed from the waist down, yet he is able to walk again after the crash (contradictory, right?). We learn about the double lives of characters like the Kwons. Hurley seems to have both the best and worst luck of all time; what drew him to this place? The mysteries come after the tail end of the pilot, where you sense something out there is here. Episode two introduces a polar bear in a hot-enough climate. Clearly not is all that it seems. Still, season one is about getting to know more about these characters, but part of that is being introduced to the oddities of this island.

This is when season two kicks in: the unknown begins to prevail. We are well acquainted with the characters, but we are still learning more about this island and its many absurdities. This goes beyond the seemingly paranormal at this point. There are actual histories on this island. There are other civilians here that lived from before the gang we have become attached to. The backstories keep coming, but they’re only there to detail more of the lives that we’re familiar with (with enough twists to keep us going). However, it is obvious that Lost now is prioritizing its ability to throw its audiences in for a loop. Every episode of this show ends on major cliffhangers; even all of season one, which came before. Now Lost was taking a plunge with confidence: this is determined to be the most unique television experience of its time.

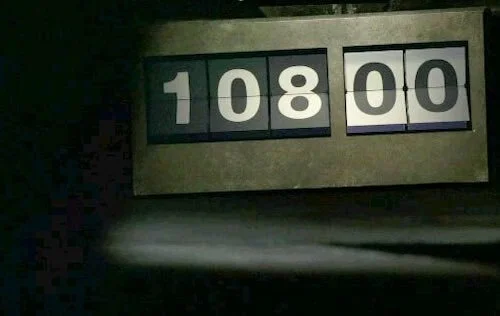

By now, we’re familiar with the hatch: Lost’s foray into a completely philosophical territory. Here was hidden clues about what was to come, as well as challenges that tested the wits and fortitudes of the survivors of Oceanic Flight 815. Each episode before used the lives of the living to sprinkle additional hints about the series’ true intentions, but now we’re staring right in the heart of the series. Here is a button that has to be pushed every one hundred and eight minutes. Here is footage of who came before you, and the barest of explanations as to why we are here. Lost was almost biblical at this point with its existentialism, mythology, and fables. It was only season two, and already the series was titanic. It became an event more than a series. People were trying to crack its secrets together. The show’s lore became parts of pop culture (how many times do we still see the numerical sequence 4, 8, 15, 16, 23 and 42?). It was unlike anything before the internet age (concerning television, anyway).

One of the biggest twists occurred in the character Benjamin Linus, who is first captured (possibly intentionally) under the pseudonym Henry. He seems like a feeble rat that the main characters — that are aware of him, anyway — wish to learn from (or use); he’s really the smartest brain in the entire series, and arguably the main villain. It’s a brilliant transition pulled off by a powerfully nuanced performance by Michael Emerson: possibly the only person and character that could usurp the title of strongest character from the many castaways we’ve gotten to know really well. Season three was the first season where his true revelation comes to shine, but that isn’t the only interesting thing happening here.

Season three is the last season to surpass twenty episodes, and it’s the sign that Lost was maybe too advanced for where it was placed. I consider Lost to be one of the greatest series of all time, but it isn’t really a perfect one (I’d argue most series aren’t, to be fair). Having to meet a quota of the amount of episodes of standard network TV just wasn’t working with Lost. Some storylines were being beaten like dead horses. Some episodes felt a little redundant. Lost was starting to feel episodic when the series was the height of cryptic serialization of the 2000’s. I recall talking with Gabe Kanter, my friend and a co-host of TV Sessions (a podcast that Films Fatale features) and he warned me about the episode that was to come once I was marathoning the series. That episode would be the one about Jack’s tattoos, which may have passed for something like C.S.I. but almost had zero relevancy in a show as intricate as Lost. Now the minutiae was getting lost in the details. This was when Lindelof and Abrams had to put their feet down. Lost had to have fewer episodes per season. It isn’t cut out to be spread this thin. We don’t see too many dramas reach twenty or more episodes anymore, but Lost was one of the final reasons why: quality will always surpass quantity. Quantity worked more back during the old days of television, where you could stumble upon it at any week. Now that we have access to all series, it’s redundant to wring a series out of so much substance just for numbers.

Season four had nine fewer episodes than three (a nice, crisp fourteen episodes), and Lost returned with debatably its finest season. Now we were nearing the end of what seemed like an actual escape from the island. Not only that, but the flashbacks were done. We know these characters and their histories. Enough, already. Well, now we were cutting ahead with the flash forwards: a glimpse at life post-escape, and the highest assurance that — finally — we would leave the island for good. However, like I brought up, “lost’ as a title is more than just being stuck in a remote place. It’s about much more, indeed. The characters were still emotional, mental, and ethical messes. Now, they’re torn as individual identities. These flash forwards present us without any resolution, but rather curiosity about what happens after the escape: why are these characters still like this?

Furthermore, we are gifted “The Constant”: a modern day La Jetée, in the sense that it’s romance that is elevated past the confinements of time. My favourite character Desmond leads this episode, and he experiences flashbacks in an almost lucid way (he’s quite literally reliving them). He hops back-and-forth through time, and for once the series is less invested in developing more mysteries than working with the innovations that it presently has. It’s a beautiful episode of television that actually somehow makes the most amount of sense, even outside of context; I feel like the passion and genius of the episode would radiate even with little previous knowledge of the series that this episode comes from. This is what allowing the show to breathe could do.

Season four ends with the literal disappearance of the island, and the schism of the storyline (of the “present”) into two different universes. Now, we are beyond lost in a whole plethora of ways. The series has only answered a little bit, but it has opened up so many more doors. I can’t remember the book I read, so please forgive me, but I do recall studying Lost back in my undergrad; the series was actually still on the air at this point. The text likened Lost to being a never ending fractal pattern. Too many ideas have been spurned, and not enough resolutions have concluded anything. It’s as if the series was predicted to have completely no solace, since it it wasn’t actually fully fulfilling its creations. If the series was in its fifth season with only one more to go, and there still was so much left to answer (we still don’t fully get who or what the smoke monster is!), I don’t blame this writer for being skeptical.

Finally, season six was here. The final rounds of one of television’s most enigmatic series. This was meant to be the providing of answers millions of awaiting viewers had dreamed of. What resulted was sudden disappointment. Before we get right to the issue, let’s see what six entailed. No longer were we flashing back, forward, or even to a separate timeline. We were flashing “sideways”: characters were living two separate lives. One where the plane never crashed, and everything carried on as it was meant to, and another where the present was a dismal nightmare stuck on the island (after the escapees went back seasons ago, due to being driven by this unknown force). These flash sideways are actually a purgatory of sorts: the ability to live amongst all of the dead. At the same time, the “real” storyline was beyond mythical at this point, with actual demigods being the source of the powers of the island. This also didn’t bode well with viewers. The finale was considered a dud.

However, I did say that Lost was made at the best time it could be, but we can now review the series in full (good luck with that, stupid cliffhangers!) at any time and in any way. Like the actual series, Lost transcended time overall. It’s only been eleven years, but I think Lost and its finale have aged better than how it was initially received. In hindsight, the entire series is about fate. Fate is what kept everyone located, no matter what age, place, circumstance, or timeline. Not even in life, death, or another dimension. Fate is inescapable. The accident would have to be experienced, since fate said so. Knowing all of this, so many of the events add up. The prophecies that Lost would remain incomplete were wrong, outside of maybe a couple of loose ends (the casting of a young Walt who aged too quickly and the character had to basically be tossed, for instance). Otherwise, the actual bulk of Lost adds up, and revisiting each and every eccentric storyline and element only enriches the imagination at place here.

At the end of the day, this felt like it was mostly Damon Lindelof’s child, even though it stemmed from Jeffrey Lieber’s idea. Lindelof would only get better with his followup The Leftovers (which will absolutely be covered in Perfect Reception), but it’s interesting to see how HBO allowed him to completely fulfil his vision. No over scheduling of episodes. No expectations that would guarantee letdowns. Lindelof was able to go wild. He would do so again with Watchmen: another brilliant series. Both HBO staples allowed Lindelof to fully realize these modern television mythologies of spiritual, psychological, and metaphysical levels. Lost was a show that shouldn’t have gotten the majority of the world tuning in, and yet it did. Lindelof clearly forever has wanted to draw people into these near-religious experiences of meta storytelling, which is what Lost ended up being. People expecting something more standard network TV did not get that. Then again, notice how I said The Leftovers and Watchmen were HBO. That’s what I was saying earlier. This could be the last network show to be this daring. During its initial run, ticker bars at the bottom of the screen were giving us hints of what happened previous episodes (so we could enjoy this current sequence at the fullest). Online forums were going crazy with discussions. In an internet age where the world could shrink, Lost became the number one television way to shrink it even more. It made all TV junkies feel the same way that Jack both starts and ends the series (a nearly identical shot of his laying body staring up at us): found. Somehow still being before its time despite being made at the only time it could exist, Lost can also finally now be found exactly as it was meant to be.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.