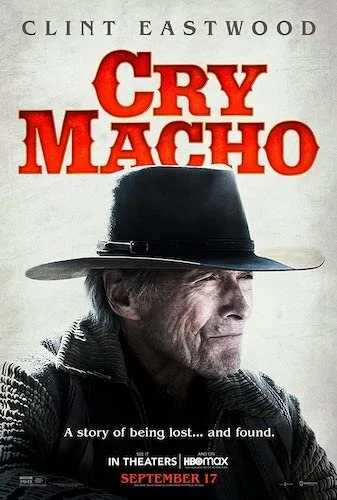

Cry Macho

Written by Cameron Geiser

With the release of Clint Eastwood’s latest film, he continues to deconstruct the very onscreen persona that he built in the first half of his cinematic career. It’s a trend that I believe he began with his 1992 western Unforgiven. Cry Macho does much of the same in terms of it’s themes, but it’s a far more mellow journey, and one with humility to boot. The relaxed pace of the story is, somewhat ironically, a change of pace from most of Eastwood’s filmography. Yes, some of his classic westerns may have had long running times with slower paced scenes of tension, but this time around the old man seems to have let go of unnecessary concern and angst. The film stars and is directed by Eastwood, who plays Mike Milo. Mike’s a washed up former Rodeo star who broke his back one fateful day and went down a dark road of alcoholism and addiction to pain pills.

In the beginning of the film Mike’s still working for the same ranch he’s been at for years and ends up being fired and then hired a year later by the same man, a ruffled Dwight Yoakam playing a decent man with an ounce of sleaze, for a specific request. The two have had their differences over the years, but they have a mutual respect for each other, so Mike hears him out. His former boss wants Mike to cross the border into Texas to retrieve his son, Rafael or Rafo for short (Eduardo Minett), from his supposedly abusive Mother who lives in Mexico City. As Mike feels that he should repay his debts, he acquiesces, and heads for south of the border.

This is a film that feels incredibly personal to Clint Eastwood. It’s another script similar to Unforgiven in that he’s kept on the back-burner for roughly thirty years until he thought he was the right age for the project. The character of Mike Milo isn’t just a stereotype, sure he may be a cowboy, but the nuances of the character reveal a human core underneath the shell of machismo that he used to be concerned with. Mike’s a caring person, he’s incredibly in touch with animals and knowledgeable enough to act as a small Mexican town’s veterinarian of sorts while he and Rafo are staying there during the second act. Which, yes, after discovering the truth of Rafo’s life in Mexico City under the thumb of his mother’s criminal underworld connections, Mike convinces Rafo to journey north to Texas to see his father. The only catch? That Macho the Rooster must come with; a small price to pay in Mike’s mind. While stuck in that small desert town, they encounter a warm and welcoming cantina matriarch in Marta (Natalia Traven).

Besides some coy flirting between Marta and Mike, these scenes give Rafo the chance to be a young man for once, and for Mike to feel useful again as he assists the locals with his skills as an excellent ranch hand. These moments and beats layer the duo with a refreshing and realistic sense of characterization. The second half of the film is almost entirely a road trip movie that never ignores or loses it’s stakes, but allows its characters time to tackle the journey together with a charming sense of adventure. The pair have their cars stolen, smashed off the road by the kid’s mother’s goons, and broken down by neglect. They avoid roadblocks and checkpoints with federales by leisurely taking side roads and darting into small churches to get out of the rain. It’s all in the service of a quality story with a mid-budget nostalgia that feels fresh due to the general loss of movies like this. They don’t make ‘em like this anymore.

Cry Macho revives some of Clint Eastwood’s neo-western tropes from the early ‘90s.

Given the themes of the film, Eastwood still maintains the masculinity so associated with his past roles and offscreen persona, his character still points guns (though only once in this film), punches villains in the face, and still rides horses. Though there were a few shots where it was clearly a double for some of the rougher beats where he’s breaking wild mustangs for a local rancher in the small town. His age can be seen and felt this time around, it’s certainly apparent in his movements and stride. However it should be noted that since this is a character who’s had his back broken decades ago during the height of his fame as a rodeo star, his hunched gait and weathered face work for this character’s history. It certainly informs his past as someone who’s lived with the weight of regret and sadness. In fact, there’s a poignant scene in the third act where Mike reveals his innermost trauma, and even sheds a few tears during the tale. There was even a bit of a monologue that his character gives us late in the film when speaking to the angsty thirteen year old Rafo which essentially boils down to one of the lines, “Let me tell you something: this macho thing is overrated”. Cry Macho was a welcome addition to Clint Eastwood’s filmography, and if this ends up being his last film, it was a good way to go out.

Cameron Geiser is an avid consumer of films and books about filmmakers. He'll watch any film at least once, and can usually be spotted at the annual Traverse City Film Festival in Northern Michigan. He also writes about film over at www.spacecortezwrites.com.