Screenwriting Tips: The Hero's Journey

Barton Fink

Coming up with a solid story can be incredibly difficult. Once you get started, you’ll find it’s not as easy as tossing some lines onto a page and hoping your story will all gel together. Luckily, there are many tools that have been created over the years. One such template is titled “The Hero’s Journey”, which will be covered today. Of course, you don’t absolutely have to abide by this outline, and many films don’t. However, once you learn this ruleset, you will undeniably find it being used in many of your favourite films (well, at least the Hollywood or more mainstream works). The Hero’s Journey is so reliable, it can be seen as a go-to for getting a story started, mainly because you know for sure your story will make fundamental sense when the archetype is followed.

Created by professor Joseph Campbell when analyzing the works of classics and Carl Jung’s teachings on mythology, the Hero’s Journey is modelled around the epics of literature that followed noticeable patterns. Campbell’s checklist has been updated by numerous other writers, which is particularly useful for different story based mediums, eras, and innovations. Today, I will be using both Campbell’s model, and the updated list by filmmaker Christopher Vogler (which is pertinent for a cinema related website).

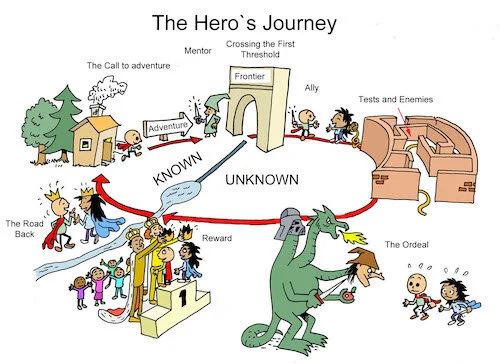

In image form, the Hero’s Journey is a cyclical tale that brings a protagonist from one spot all the way back to the same location, although they are now a changed person in some sort of way. This can be through development, a relationship or more, a discovered item, setting, or context, or in any way that allows an analysis of how said character started the story. In diagram form, here’s what this journey would look like. I chose a more fun image to use, because why not.

Even in this simplistic form, you can begin to see these patterns in many films. If you wind up watching many films, you can argue that resorting to the same formula will make most films of this nature feel by-the-numbers. You can still be inventive with The Hero’s Journey in a way that is fresh. You can also abandon using the template altogether. However, if you are a writer starting out, it is a ruleset that will help to learn, so you can at least understand the fundamentals of screenwriting (or writing of any sort) at a very basic level. So, let’s get started.

Keep in mind that the steps in Campbell’s outline are named after mythological tropes, so stories have extended what these steps are capable of over time. Also, the three phases are kept in this order, but the steps within them may be able to be swapped around or omitted depending on your story.

1. Departure

The Maltese Falcon

A journey is the departure from normalcy. Why is the character leaving? Where is the character leaving from? What causes the start of this narrative shift? There are many things to take into account with this first step, since this is the establishing section of the film. We have to learn who we are dealing with (or at least a majority of the lead characters), what they will be dealing with, and where they are dealing with it. Keep in mind a “journey” can be entirely figurative. This can be a spiritual, mental, emotional, or personal journey, and the setting never changes. For instance: a detective solving a crime in the same neighbourhood which changes them as a person.

The Campbell steps in this section include:

• The Call to Adventure

• The Refusal of the Call

• Supernatural Aid

• Crossing the Threshold

• The Belly of the Whale

So, again, you don’t have to follow each and every part. Consider the similarities and differences of having both a “supernatural aid” and a “call to adventure” in the same film, although it is possible (see Cinderella). Anyway, let’s break these points down.

• The Call to Adventure

A call to adventure is the pinpoint moment that causes the adventure to start. It could be a new client of that detective with their particular case that the film focuses on. It could be an invitation to an event, an announcement of a divorce, or any sort of instance that changes the established world that the film has spent however amount of time to establish for you. This will seemingly change the character’s life, and we know it from there and then.

• The Refusal of the Call

Then there can be the refusal of that call, which teaches us more about this person. Why would the detective not want to take this case? Does it remind them too much of a family member, a lost love, or something else traumatic? Of course, a refusal isn’t entirely necessary (the protagonist could be eager to go on a quest), but it can be important to a particular story.

• Supernatural Aid

If applicable, the “supernatural aid” can then come into play (say, a fairy godmother that can make a mission come to life, or a genie to grant wishes). This can include weather changing, religious connections, or any “external force”. This is an extra push to get the hero to be able to start their journey either if needed (if they are missing what is necessary to keep going), or to motivate them to do so (if they are taking part in a “refusal”).

• Crossing the Threshold

Then, it’s about crossing that threshold: leaving Bag End, saying yes to the case, signing the divorce papers, whatever it takes to start a new chapter of life. This is the most important part of the departure, because this is the actual departure. Missing this step will be missing the entire section.

• The Belly of the Whale

Crossing the threshold goes hand-in-hand with the final point: the figurative “belly of the whale”. Crossing the threshold is one thing, but entering new, daunting territory is what reveals more about a character or mission. What’s this character like when they are uncomfortable, or how do they approach danger? Is this a dangerous new world they have entered? Is this the call after the divorce papers have been signed, notifying the lead that they will regret what they have done? Is this the walk into the street where the detective has been hired to stake out? What big leap have we just taken, and why is it exciting for us to take this leap?

With all of this in mind, we now approach the meat of the story: the initiation of every obstacle from here on out.

Widows

2. Initiation

So, there must be an initiation of change; the implementation of knowledge accumulated thus far to overcome an obstacle (or many obstacles). A villain is introduced, or a problem arises in a plan.

Here are the Campbell steps in this section:

•The Road of Trials

•The Meeting with the Goddess

•Woman as Temptress

•Atonement with the Father

•Apotheosis

•The Ultimate Boon

•The Road of Trials

The road of trials is one of the more literal steps here. It represents the obstacles in a hero’s way, akin to the trials that, say, Hercules or Odysseus had to endure in their respective tales. These are moments that strengthen a character once they surpass their tribulations, or weaken a character once they succumb to them. You’re looking at a road closure on a trip, the need for money after being robbed, or the detective has wound up in the house of the suspect they’re tailing and they can’t get out.

•The Meeting with the Goddess

The meeting with the goddess is a bit more figurative. Say this is a character that can be used as a checkpoint in a positive way; someone who can heal the protagonist, or help them in any way. A kind person taking care of the hero after they collapsed from exhaustion. A friendly face that knows where the next location is.

•Woman as Temptress

The “meeting” can lead into the next section, hence Campbell’s dated use of gender specific labels like “woman as temptress”. In a more literal sense, this can be a femme fatale in a noir film (a romantic or flirtatious character that tricks the detective); however, we can break out of these tired confinements, I’m sure. Other characters can include a friend that is lying for their own benefit, a deceptive move to thwart the character, or any sort of subterfuge. Consider this an obstacle that the hero is not prepared for, since the road ahead wasn’t presented to them.

•Atonement with the Father

An atonement with the father is pertinent to some tales but not all (just like a number of these steps), where a character maybe realizes they have what it takes to ask a loved one for forgiveness now that they have developed. After being tricked by the deceptive character previously, maybe the protagonist goes back home and begs for forgiveness because they now know they should have listened. Maybe the entire trip was part of the refusal in the first section, and the lead character has to go back to their boss to apologize. This can be used as a positive (a bonding between characters) or a negative (a hero giving up and second guessing their mission).

•Apotheosis

Here comes the most fulfilling part of a Hero’s Journey: the apotheosis. Stemming from Greek (loosely translating to “the making of a God”), apotheosis is the art of a character becoming the best version of themselves. This is the final turning point in the conflicted portion of a story so the hero can finish their quest once and for all. You know when a character in a corny fight scene says their line and comes back with more strength than ever? It’s kind of like that. The detective is caught in a fight, but steps back up after keeling over and goes all in. Luke Skywalker finds the force in him at the right time. Whatever it takes for the hero to complete the quest fully changed and with all of the experience they have picked up earlier on coming into play.

•The Ultimate Boon

The ultimate boon is the climactic situation of the film, and the final step in the initiation phase. After the courage mustered earlier, the final act takes place. Luke Skywalker delivers the last blow. The detective tosses the main villain into the meat closet and they are locked for the cops to find them in. The race is finished. The main characters embrace in that conflict resolving kiss. Whatever that moment may be is the ultimate boon.

After that, we’re ready to resolve the entire story.

A Touch of Zen

3. Return

The hero makes their way back to square one, whether it’s returning to where they live, entering the world a new person, or returning to the same old job with a fresh mindset.

Here are Campbell’s steps for this final section:

•The Refusal of the Return

•The Magic Flight

•Rescue from Without

•The Crossing of the Return Threshold

•Master of Two Worlds

•The Freedom to Live

•The Refusal of the Return

Like a mission can be refused, a return can be refused as well. Say a character doesn’t feel fit to return to that dead end job they once held now that they are a new person. The detective doesn’t want to get back into this line of work anymore; that last case was hell. Jake doesn’t want to leave Pandora. A refusal to return can be rebutted later on by the other steps, or it can lead into the new ending with the refusal taking place (Jake ends up in Pandora for good, for instance).

•The Magic Flight

The magic flight is nowadays mostly figurative. It’s the return with the rescued item or person, or the new traits of a protagonist that has claimed victory. The term “magical flight” is still useful to a degree, because films can often skip this step and cut to the future, or include a montage back (if not utilizing this step in other ways); we “magically” get to where we need to go.

•Rescue from Without

”Rescue from without” is the saving of the hero as the result of the ultimate boon or any event after. It can be a friend that went missing, only to return as a “twist” in the climactic scene to save the day. The detective falls off a cliff, but is grabbed by a hand that pulls them up to safety.

•The Crossing of the Return Threshold

If the return takes place, then the threshold has to be revisited. We see the changes of a character going into unknown territory, so it only makes sense that we see what they are like as new people in old territory. The detective can no longer look at their office the same way again. It isn’t back to business as usual.

•Master of Two Worlds

Threshold or not, being a master of two worlds means the character can now travel between both universes with no problem. A warrior that has conquered new territory is welcomed back home, but also feels comfortable in their new lands. A cowboy is welcomed in both towns after saving the day in a place previously foreign to him.

•The Freedom to Live

The lead character can feel unburdened by the inevitability of death, as previous struggles no longer plague the character. This is basically your “they lived happily ever after” moment. The detective retires and goes to live in Honolulu to enjoy life. A hero ventures to new territory after being celebrated back home. The next mission is laid out. Sequels are teased (God forbid).

To recap what we have covered up until now, here is, once again, the Joseph Campbell original version of The Hero’s Journey:

Departure

• The Call to Adventure

• The Refusal of the Call

• Supernatural Aid

• Crossing the Threshold

• The Belly of the Whale

Initiation

•The Road of Trials

•The Meeting with the Goddess

•Woman as Temptress

•Atonement with the Father

•Apotheosis

•The Ultimate Boon

Return

•The Refusal of the Return

•The Magic Flight

•Rescue from Without

•The Crossing of the Return Threshold

•Master of Two Worlds

•The Freedom to Live

Now, I honestly don’t think I need to go through Christopher Vogler’s model, and you’ll see why right now. Here it is.

Departure

•The Ordinary World

•The Call to Adventure

•The Refusal of the Call

•Meeting with the Mentor

•Crossing the First Threshold

Initiation

•Tests, Allies, and Enemies

•Approach to the Inmost Cave

•The Ordeal

•Reward

Return

•The Road Back

•The Resurrection

•Return with the Elixir

Notice how steps are either similar or identical to what Campbell initially wrote? It’s just more digestible to understand with Vogler’s model, especially with the vagueness of each step allowing for interpretation. Otherwise, they cover the exact same principles.

Using A Film As An Example

To wrap up this lesson, I think it’s only fair that an actual feature film is dissected into the above steps, so it makes sense in a complete sense. I’m going to use Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water as the example here. I’ll use Vogler’s model, since his is meant for screenwriting, and it’ll transition even better to the breakdown below.

This analysis will explain all of The Shape of Water. This will ultimately spoil the entire plot. Reader discretion is advised.

So, let’s go step-by-step and revisit this film. I will only be using Elisa’s journey here, otherwise we’d be here all day (there are numerous characters that have their own well-written storylines that follow similar guidelines).

Departure

•The Ordinary World

Elisa is a cleaner for a laboratory, who has been neglected by the world outside of her coworker Zelda and her neighbour Giles. She has scarring on her neck, which may explain why her character is mute; a trait that has rendered her an outcast in a less-understanding ‘60s America.

•The Call to Adventure

A mysterious vessel is brought into the laboratory, and there is a certain mystique surrounding it. Elisa is intrigued.

•The Refusal of the Call

Elisa doesn’t really refuse the opportunity, but she continues working, which can constitute as a shrugging off of said “call”.

•Meeting with the Mentor

Elisa doesn’t really check in with other characters about this particular matter, but she still confides in Zelda and Giles in general. This gives her some time to marinate on whatever she has seen already.

•Crossing the First Threshold

Intrigued after a series of events, Elisa goes to the vessel to see what exactly is going on. She discovers an amphibian human referred to as the “asset”. Since he doesn’t have a name and asset is mean, I’ll stick to Wikipedia’s insistence of “Amphibian Man”. She begins to communicate with Amphibian Man via sign language, and they become friends.

Initiation

•Tests, Allies, and Enemies

Colonel Strickland has already proven to be an enemy to Amphibian Man, but is now a threat to Elisa, who sympathized with Amphibian Man after he is repeatedly abused. She vows to break him out of the laboratory and take him home. The break out is successful, and now Elisa is struggling to keep Amphibian Man alive in her home.

•Approach to the Inmost Cave

After falling in love with Amphibian Man, Elisa decides that freeing him into a nearby salty body of water is what is best for him. She is also gravely in danger, now that Strickland knows she is sheltering Amphibian Man.

•The Ordeal

Elisa is finding it hard to say goodbye to Amphibian Man. Meanwhile, she gets murdered by Strickland, who is stopping at nothing to steal back Amphibian Man.

•Reward

In this particular film, there isn’t really a reward in this portion of Eliza’s story. Although, we must continue.

Return

Only one of the endings here applies to Elisa.

•The Road Back

There is no road back for Elisa.

•Return with the Elixir

That also means there’s no return with any elixirs (or important objects).

•The Resurrection

This is where it all happens for Elisa. Her reward, missing from her “initiation” phase, is her life being gifted back to her by Amphibian Man. Her scarring on her neck develops into gills. She is free to live an entire life with Amphibian Man under water, away from the unforgiving world she lived in previously.

Conclusion:

Elisa has overcome many obstacles, including being intimidated by people like Colonel Strickland. She has grown an appreciation for life, now that she is in love and has access to a world that will be more accepting of her. She has learned to stand up for herself, but remains as kind, charming and optimistic as she always was.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.