Twelve Non-Director Activities for Aspiring Directors to Explore

The Stuntman

I’ve been wondering what kinds of lessons would fit the “Directing” section of Films Fatales’ Masterclass series because it’s difficult to say much about the field. A director oversees what’s going on and asks for changes. They decide what the tone of the film will be. If we’re speaking about filmmakers who are solely directors (none of these producer, screenwriter, actor combinations), they’re basically funnelling the ideas and work of others into their own perspective. What more can be said?

Well, what I’ve decided is that analyzing filmmaking (strictly from a directing standpoint) this way can be quickly concluded. However, these are “Masterclasses” after all, and part of that is actually providing tips for aspiring filmmakers (something we will do for each of the sections, outside of “Film History”). These aren’t just for helping people figure out the importance of a field, but to help those actually in their fields. Directing is so general, though. Where does an aspiring filmmaker begin? Don’t they just make films and get good experience?

Well, we’re going to go a bit of a different route today. For anyone that’s wanting to start making films and expand outside of the fun stuff you make with your buddies, we’re going to take you away from solely directing. If anything, I believe a director needs to at least have an understanding of every field. This is to ensure that a filmmaker knows what capabilities are at their disposal, as to not under or over expect from their crew. In order to do this, you’re going to have to do twelve things that aren’t actually directing.

Note: These are all very basic starting points for those who may not be attending film school, or additional resources for current and/or past students.

Write a Short, or a Scene

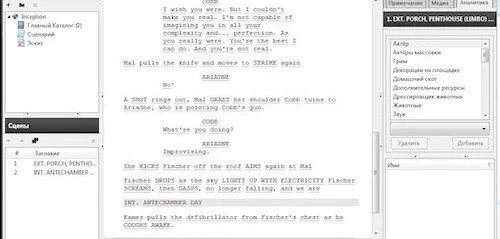

Celtx

I can guess that most beginner filmmakers have already written (or improvised a story on the spot), since they’ve had a narrative in mind that they wanted to tackle. If not, this is absolutely where you have to start. Many directors write (or co-write) their screenplays and/or stories. If not, they have a handle on how to adapt these words in their own way. You have to figure out how screenplays work. The starting point is to look up your favourite scripts ever. Chances are they’re free to read through online. If you’re stumped, here’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Network, and Back to the Future. Otherwise, stroll through everything that Screenplays For You has to offer that catches your eye. Figure out what makes these screenplays brilliant. Is it the dialogue? The resolution of plots? The complexities? The character development?

Now, it’s time to write. Using a regular word processor is a bit of an extra hassle, since screenplays are formatted a specific way. That’s why there are a number of resources you can use, including Celtx, WriterDuet, and Scrivener (amongst others). For a free tool, StudioBinder have their own free software for beginner writers.

This will help you understand story structure from a pre-production viewpoint, which will help place the story in the back of your mind the entire shoot. Instead of just relying on the script of another, fully understand why the script is the way that it is. This also allows you to feel comfortable to make your own shots; if you disagree with an action in the screenplay, you can now boldly create your own changes and understand how you are helping the screenplay and not taking away from it.

So, now you just write a short film or a scene. Write a story that won’t take long. Figure out introduction, the middle act, and the conclusion. Try re-writing different drafts. See what your screenwriting friends think of your work. Don’t start off with an opus. Just create something small that will help you harness your skills. Then, do it again. If you feel like it, work on your screenwriting skills until you know the medium inside and out, and can confidently look at anyone’s screenplay and know all of the functioning parts as you read through them.

Draw A Story Out: Become Familiar with Storyboards

Flickr

If you are comfortable with filming on the fly, you may be in for a rude awakening when you hit a creative block one day. Storyboards are a common practice in film anyway, so it’s something that you should probably invest some time into now. Some directors do their own storyboards, which is fine (and usually incredibly helpful for a production).

However, I want you to pick a favourite book, and select a portion or a chapter. If you were to adapt this novel, how would you storyboard it out? If the story has already been adapted into a film, please try to refrain from copying it. This is about exercising your vision. To get you started, Boards has assembled a large number of storyboard examples for you to see right now. Figure out why these are good storyboards. Do they offer a great starting point for production? If so, how? Is it the framing of images, the delivery of information, or the uses of colour?

The best free option is to draw your storyboards yourself. If you’re wanting to collaborate with some friends online, or want an easy-to-share method, Boards is a great tool for storyboarding, as well as Storyboard That. Remember that artistic capabilities aren’t important, as long as the images you have in your mind are still decipherable to some degree by your cast and crew.

So, storyboard that story, and show some loved ones. In fact, maybe even show a fan of the same source material, and see if they understand what part of the story you have just adapted. Storyboards aren’t just for self reference, but they’re meant for all involved party members to understand. If your storyboard is difficult to figure out or understand, ask or discern why, and make the proper adjustments.

Act in a Class, or With Your Friends

Arrested Development

A major part of directing is trying to get the most out of your actors. However, how can you fully do this if you don’t act yourself? Sure, acting on the surface is just the art of make belief, but there is a lot of work and practice that goes into acting. These include breathing exercises, revisitation methods, and other activities that performers regularly work on. You can yell “be more sad” all you want to get an emotional scene, but that isn’t helping anyone. If you’re not getting what you want from your performer, you have to understand what they can do from their perspective.

The best way to go about this is to enrol in an acting class, either a local weekly event or a non-major course in university and/or college. If these aren’t something you can do, there’s always doing the free route. Get some friends and act out your favourite scenes, or start your own improvisation club. Either that, or offer to act in your friends’ productions; even being an extra or a very minor character puts you in the space of people who act for a living and/or hobby. You can get some valuable advice by working with performers, especially if you inquire their acting methods between takes.

If you want to get the most out of your performers, you have to think like a performer, and know how they conduct emotional responses on the spot, deliver lines, create personal backstories, and more.

Attend or Research Speech Classes

My Fair Lady

Very similar to the above point. A good portion of acting is diction and projection. Maybe you’re seeing eye-to-eye with a performer on their emotional responses, but their delivery just isn’t cutting it. You have to resort to the even more basic art form of speech. Knowing how to speak properly (and even professionally) will help you navigate through these hiccups.

Universities and colleges usually offer public speaking courses; if they do, they can be linked to theatre. Again, if this is not an option for you, there are luckily many free resources online. Top Resume has a great list of various sources, including TedTalk and American Rhetoric, with examples and tips on how to approach the art of public speaking. You will learn breathing, projection tips, spacing out words, pacing your thoughts, and other tips that apply to both the real world and to acting. It doesn’t hurt to brush up on your interview skills in the meantime either (this has many benefits in the film industry, including pitching films).

Research Production Notes, Contracts, Budget Sheets, Et Cetera

The Producers

Chances are you’re not dealing with big time producers if you’re an aspiring director. However, understanding all of the ins-and-outs of production is quite useful. These include budgeting (or figuring out feasible work-arounds if you have grand ideas but lack the resources), contracts (or where you can shoot, what you can shoot, and who you can shoot, and what processes go into these agreements), scheduling (how to map out your production) and more. Sure, you’re likely just making films with your friends, but understanding how a film is made via business decisions and expenses is imperative if you want to get anywhere. Even if you never produce a film, being on the same page as a future producer definitely helps.

For an example of production notes as to sell a film, Deadline has this copy of the notes used for The Dark Knight Rises.

For a series of templates, Examples has, well, examples for your leisure.

For shooting schedules, Sample Templates has some sample templates.

For budget report templates, please refer to Template Lab.

For location agreements to shoot at any place, go to Shoot My Place.

All of these examples are dry and tedious to read, but you will become familiar with what are reasonable requests for your producer. Mapping out your shoot, figuring out how to achieve everything you want contractually and financially, and organizing your vision through a business, legal, and economic mindset is a habit you’ll want to get used to. As a director, you can only do so much with your vision.

Spend Some Time with a Camera

DaVinci Resolve

If you’re a brand new director in training, chances are you’ve already tried to shoot your own stuff, either with a camera or a smart phone. If not, it will absolutely help to become familiar with how cameras function, as well as lighting and colour practices (during and post production). Grab a videographer or photographer friend, and get shooting. Don’t even try to shoot a scene or story at first. Just pick a subject (it can be a rock, even), and just experiment. You’ll likely learn very quickly the importance of lighting rigs (bulbs, bounce boards, et cetera), but you’re not trying to create a masterpiece right now. Even understanding still photography can help. You can also mess around with smart phones by recording this way; many models come with pro shooting modes that you can set up with personalization.

If you aren’t familiar with settings on a camera including aperture, shutter speed and ISO, Peta Pixel has a great beginner guide. If you are familiar but need a refresher, there’s a cheat sheet from SLR Lounge for you.

Chances are you’re working digitally and not with film (if you are, perhaps with a Bolex 16mm camera or something similar, many of the rules above apply). Ask your videographer pal about tips, reading light meters, adjusting to different settings and times of day, and other essential parts of being a film photographer. Just fool around (easier to do with digital equipment, otherwise you’re left with tons of wasted film) and see what you end up with. It may help make on-spot decisions about where and what you want to shoot a lot easier.

Then there’s the post production game, which includes colour correction. The software DaVinci Resolve is available as both free and paid, but for your purposes, the free version will work just fine. Toss in a clip and mess around with the colour correction. See what you can achieve in post. This may help you solve on-set dilemmas; why mess around for hours trying to get a cool blue light from a natural source if you know it’s easy to get in post?

Spend Some Time with a Microphone

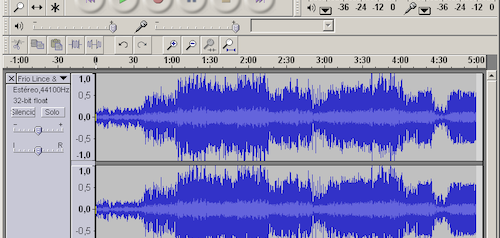

Audacity

Similar to the above point, it’s good to get acquainted with how films sound. Sound designers and experts will know what locations, ideas, and objects just simply won’t work no matter how hard you try, and understanding the fundamentals of sound recording may save you many hours of futile attempts. Grab a buddy that has sound recording equipment, or fool around with your mobile phone again (however, I can guarantee that using a smart phone will result in disastrously sounding recordings, but this is not meant to be a masterpiece). Maybe pick a scene from a film you like, and read out the lines (unless you want to practice acting, you don’t have to do a good job) and place your recording device in different vantage points. Figure out what works best. Chances are you’ll realize a boom mic is preferable, and trying to practice this type of recording won’t be easy without the equipment. Either way, it isn’t so much about the recordings. Record whatever you want in different ways.

What we’re more focused on is seeing what can be done with sound after the fact. You can see what can be done with sound in post. Luckily, Audacity is a famous free sound editing software that you can easily get. Toss your sounds in there, and see what recordings get clipped (when the sound wave is too large and can’t be contained, thus losing information by literally looking “clipped” on the top and/or bottom), how easily sounds can go into the red (being too loud to the point of distortion), and other various problems that sound artists work with regularly. Try and see if you can fix these recordings with various effects, or determine if they’re unsalvageable.

The best thing you can do is have a sound expert friend go through these kinds of examples with you. Even friends who are into music production or podcasting can help, since your intention is to understand the do’s and don’t’s of sound recording (dialogue and music included). Chances are your friends you collaborate with on your film will know exactly how to record, but doing all of the above will help you understand why, so you never second guess (and maybe can comprehend completely on certain decisions).

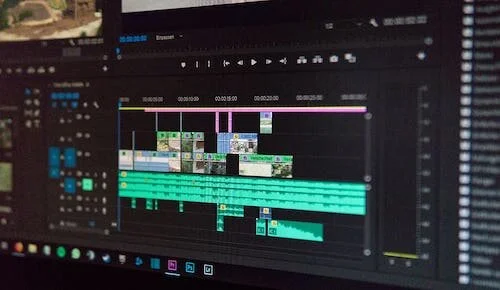

Piece Something Together with Editing Software

Adobe Premiere Pro

It may be difficult to know how a film will end up before you even reach the editing stage. So, get some experience with a video editor. This way, you’ll have a good sense of how to shoot specific scenes, what you might want to shoot (how many takes, how many variants of takes) and how much you can rely on an editor. Grab a clip, or shoot your own variety of videos, and toss them into an editing software, and assemble away. See if you can create something of substance from nonsense, or just try to make some great juxtapositions. Get familiar with the culling process.

The easiest answers for which editing softwares to use include Adobe Premiere Pro, Final Cut Pro, iMovie, and Windows Movie Maker. However, if your computer didn’t come with any of these softwares (considering Windows Movie Maker is now discontinued) or if you don’t want to spend a fortune, luckily Oberlo has compiled a list of twenty four different free video editing softwares that you can give a bash. Furthermore, Vloguide has a similar list with even more video editing softwares (a staggering forty four free programs) that you can try right now!

Put together a film, or take apart a video you have and reassemble it in your own way. Either way, figure out how modern day digital editing works, and have fun with it. Find out how an editor can tidy up for you. Figure out continuity (and try to prevent errors if you can yourself while shooting). Play with juxtaposition. You may figure out many things you’ll want to shoot as a result of learning the ropes with editing.

Now: Keep Watching Films

Amélie

Wait… what?

There’s not much more you can learn from doing what others do, outside of understanding costumes and make up (what can be possible with the means of a shoestring production) and other similar fields, but it feels like I’m circling the same ground again and again (plus, there aren’t many online resources I can give for these fields in the same way). So, the best thing you can do is just keep watching films with a director lens. Revisit films you love but haven’t seen in a while. Break down why you love them, and if they have anything to do with how they are made. Look up new films (there are countless lists of recommendations, including our own) and see what gave these works longevity (particularly well made works). The best experience for understanding films is to keep watching. However, don’t get too comfortable. Try and step into unchartered territories (for yourself, anyway). Aim for challenging works. With all of the above tips, try and see how any of them can apply to these films.

While we’re at it…

-Become Acquainted with Short Films

For the Birds

You’re a new filmmaker, and the chances of you being granted the ability and funds to shoot a feature are slim. With the above tools and your own experience, aim for that short film you can piece together and pitch. They’re much more digestible to finance, and it’s great experience. Plus, it’s one way to get your name out there. Most filmmakers have at least dabbled in short filmmaking, if they didn’t start there (many do). For your purposes, even if you have a feature in mind, aim for the short; worst comes to worst, you will try and convert your festival award winning short into a feature one day. Either way, don’t aim too high by trying to make a massive epic. You’re in a competitive industry, and the overly ambitious get shot down really quickly. Besides, shorts are an easier and quicker process to get familiar with for right now. See what you can do. If you don’t want to shoot a short just yet, do demos. Film a single scene. See what you’re good at capturing. Either way, researching shorts will help you see how they function, and how you can create yours. What can you do in limited time, with few resources, and a small crew?

-Become Acquainted with Documentaries

Man with a Movie Camera

Another type of filmmaking that can help is the art of documentaries. Seeing familiar people and subjects shot in a different way can help you differentiate between narratives and documentaries. Plus, you can see what different equipment and budgets can do for you, considering the usual finances and equipment that go into documentary films. This also helps with understanding story: how does pieced-together footages of life differ from a fabricated tale, beyond one being real and one being created? This can help strengthen your understanding of editing (how these clips add to these messages) and flow. Even if you aren’t intending on shooting a documentary, it’s wise to be familiar with all styles of film, as to understand your style and how it differs from others. On that note…

-Become Acquainted with the Avant-Garde

L’Ange

Seeing artists deconstruct film and turn it into a variety of experiments is the best way to understand the fundamentals. Why is something shot weirdly? What does this editing do? How am I connected to this film without narrative cohesiveness? Seeing a completed product broken down into an archaic, unorthodox fashion is a fantastic way of seeing the extremities of the medium. Considering that most avant-garde films are incredibly under budgeted, you can also figure out exciting ways of achieving more with less. This is how filmmakers think outside of the box. If you’re stuck, breaking your conventional confinements is the way to go, and becoming familiar with some of cinema’s more experimental examples can help you figure this out.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.