Editing: Types of Cuts

Editing is important, for many reasons. Excess moments that don’t help a visual story aren’t needed. The pacing of a film and its many moments needs to be determined. As much as the shots within a film are important to the visual language, so are the cuts that splice them together and dice them apart. Today, I’ll go over the main types of cuts used in a film, and what purposes they would serve. Over the decades of filmmaking, editing has gone from a necessity to clean up a feature (the history of editing will be covered in the future) to one of the many artistic features a film can have. Even though a cut functions almost the same way every time (the exact moment one shot ends, and the next begins), the ways they are implemented tell a unique story for each use.

Hard Cut

Your most standard type of cut is the hard cut. This means the cut from one scene to the other. It’s the most obvious assembly of scenes. To mark the end of the scene, you have a hard cut that marks the resolution of what has just happened before. It’s as easy as that.

There are countless examples of this, since nearly every film for the last one hundred years contains these types of cuts for most scenes. I’m using the start of Lawrence of Arabia, because it’s a fascinating hard cut that sets the tone for the remainder of the film.

Note: This sequence is at the very beginning of Lawrence of Arabia, so it’s not a spoiler for how the film ends. Regardless, it can still be considered a spoiler. Reader discretion is advised.

After T. E. Lawrence’s motorcycle accident, the film hard cuts to the funeral, as an emphatic statement that the focal point of this film is very much dead, and that we are going to view his story all in hindsight. We also see a comparison between the person — who died during a hobby — and the public figure, who was both adored and abhorred. This particular clip features commentary by Dave Lewis, who also classifies this cut as a “hard cut” at the right moment.

Cross-Cut

Cross-cutting is the next basic type of cut after hard cutting. It’s the practice of cutting between subjects in a particular scene. This can mean people within one location, a phone conversation between two subjects in different locations, a subject looking at something, or even a thought in someone’s head relating to what they are currently saying or feeling.

For a more basic example of cross-cutting, here is a scene from Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, with an extra fine example around halfway through, where the lead character gets on the phone; you see both subjects interacting.

For a bit of a unique example, here’s a moment from The King of Comedy, where a character creates an interaction in his head. You zip between fantasy and reality, as if it were a live, cohesive conversation.

Jump Cut

A little bit more jarring than a hard cut, a jump cut is the leap forwards in time, within the spacial constrictions of a scene. Usually, cuts will involve images that would be in the vicinity of the subject, and can either be in a linear form or a back-and-forth fashion.

One notable example I bring up a lot is the driving sequence in Breathless, where one conversation is carried over what seems to be an indefinite amount of time. We know this, because the scene cuts forward in rapid succession a number of times. It’s an unusual moment, where the discussion remains unaffected, but the visual story is broken into pieces, creating a bizarre take on the passing of time.

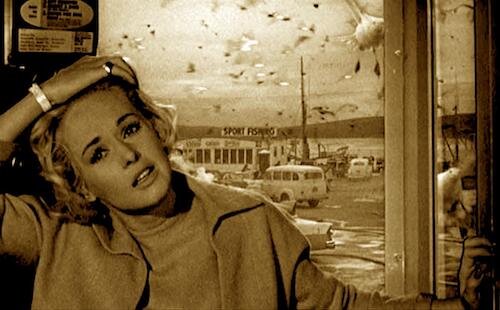

For a different type of jump cut, we can look at this scene from The Birds. In the middle of this clip, the editing cuts from the subject’s shocked face back to the spreading fire a number of times. It creates a sensation that we are frozen in time, and the spread of this fire is unstoppable. All we can do is react, bit by bit.

Cutaway

Cutaways are very common, especially the older that cinema gets. Before, films relied on what was deemed entirely necessary, and what we saw and heard was limited to the bare essentials. Once innovative films showcased the importance of finer details being a part of the whole picture (Citizen Kane and its opening of cutaways comes to mind), the idea of the cutaway became an integral part of editing. Cutaways are when we literally cut away from the main action to see what is happening around us. In their most common form, they are used to show something the main characters may be noticing off to the side or in the distance. Cutaways can also be more noticeable, like a character fading into a day dream or a memory.

For the more conventional use of a cutaway, here’s this scene near the start of The Godfather. As the couple sit together and talk amongst themselves, the film cuts to the singer at the wedding a number of times. This is done for two reasons. Firstly, the singer is discussed, so we match the point-of-view of the characters, thus filling up the spacial awareness of this scene. Secondly, it fills up the empty space during the silence of the two characters (towards the end of the clip). We never lose sight of where we are and what’s going on, and the focal characters don’t have to do all of the heavy work with establishing the scene.

Match Cut

Cutting can also lead to creative juxtapositions (something I will cover once I get into the history of editing). Of course, you won’t find a film that uses too many of these kinds of shots, but using them as a cinematic garnish or the spice for the extra kick always helps. A match cut is a transitional type of cut that mirrors unrelated subjects before and after the cut, in some sort of comparative way. This can be an ironic statement being made and then matched with (Robert Altman’s Short Cuts is full of match cuts of this nature), images that line up with one another, or focal points in movement that can line up. Usually, match cuts are used for a very specific purpose, including creating comedic parallels, or showcasing a metaphorical statement.

This iconic moment in 2001: A Space Odyssey is the bridge between two starkly different chapters: the primitive age, and the future. Once tools are discovered through bones, a bone is flung up into the air. As it is flipping in empty space, the film cuts to a flying satellite in space. The implication is clear: this is the start and the foreseeable end of the technological advancements of humanity.

Contrast Cut

Unlike a match cut, contrast cuts are purposefully meant to create dissimilarity. Contrasts are often utilized in film to emphasize the intention of particular moments; this can include the sadness or joy of a moment, when compared to a starkly different image.

Note: This is the final moment of La Vie En Rose and is considerably a spoiler. Reader discretion is advised.

During this final scene in La Vie En Rose, the sung performance is intercut with images of death and childhood, which already contrast each other. Within the sequence, there’s an even bigger contrast, showcasing the importance of music throughout the entire life of this artist; this is particularly important, given the context of the song being performed (“Non, je ne regrette rien,” or “no, I don’t regret anything”).

Parallel Editing Cut

In line with how contrast cuts and match cuts utilize focal points artistically, parallel editing cuts create seamless transitions with different subjects. This can be used as an aesthetic means to correlate subjects engaging in the same activity but in different places. A common type of use for this cutting style is for chasing sequences, either on foot or by car (amongst other types).

Note: This is towards the end of Charade and can be considered a major spoiler. Reader discretion is advised. As well, the music in this clip is not in the original scene.

This climactic moment from Charade features a fantastic parallel edit cut between the two characters, as one runs away and the other is in pursuit. There’s an illusion created, where it’s as if the characters are the same, given their relation to the framing of each shot, and the clean cutting as pillars zip past them.

J and L Cuts

Incorporating sound into the editing process, the way that audio is used amongst transitions can also be utilized wisely. For cross-cuts and hard cuts, there are two different types of cuts that can be used for either of them, if the editor feels the sound from before or after a cut is important. These are known as J and L cuts, and it all has to do with how the cuts look. Refer to the image below.

Credit: Vimeo.

So, a J cut is when the sound of the next scene seeps into the previous scene, and looks like a “J” (either on literal film, or on an editing software, like in the image above), as the audio starts before the visuals do. This is a technique used to set up the next scene for a multitude of reasons: get the viewer excited for what’s to come, trick the viewer with what will appear on screen, or simply to tidy up a moment where a hard cut just didn’t make sense.

In this transition of scenes in Mulholland Drive, the characters are off to a movie set. The music being lip synched in the next scene arrives before the visual scene itself does. This creates a gentle transition into the next moment (which is slowly zoomed out of, continuing this mellow fluidity).

Additionally, an “L” cut is the exact same type of cut, but in reverse. So, the sound of a scene carries over into the next scene. Similarly, on film or on an editing software, this type of cut will make a “L” shape”, as the audio carries off longer than the visual. Reasons for this type of cut are also plentiful, including the turning of a conversation into a voice over (either for a memory or a fantasy), to allow a previous scene to ease off into the next scene gradually, or to let the excitement of a previous moment drift off naturally and not be stopped abruptly.

Note: This is towards the end of Hannah and Her Sisters and can be considered a major spoiler. There is also the discussion of suicide. Reader discretion is advised.

In this pivotal moment in Hannah and Her Sisters, what starts off as a conversation turns into the cinematic recollection of a previous event, as the character’s rebuttal continues into the next series of visual images, thus turning into a narration of what we are seeing. We also understand that this is being relayed still to the other character, even though we are seeing these images.

While these are obvious examples of J and L cuts, please note that there are far more common and frequent uses of these cuts, even in normal scenes. If a character is discussing something and we cut to the other character and still hear the first character, then that is still an L cut. We don’t have to drastically change scenes. As long as the audio begins before a visual, or continues after a visual, it is a J or L cut. You will find these in nearly every well-edited scene with numerous notable cuts containing dialogue within the last few decades.

Dynamic Cut

If you want the editing of a sequence to particularly stand out, perhaps to quickly burst through a part of a story, then you can use a dynamic cut. This is the quick flurry of images that are tossed into action packed and/or exciting films, as they continue the exhilarating pace of the entire feature.

For a good example of this, watch the final moments of this clip from The World’s End. The beers being poured (also let’s not forget that lone water) are assembled together through dynamic cutting. We don’t slowly see these being poured, nor do we not see them at all. We get the idea of the four beers being poured, with the water serving as the visual punchline. This is achieved well through dynamic cutting, as we see the pattern being disrupted.

Montage

Think of montage cutting as the more graceful version of dynamic cutting intended for longer periods of time. Montages are the series of events that detail what has happened in a significant amount of time. It’s a useful way for a film to leap forward into the future. The audience still gets a sense of what is going on without wasting valuable time, and important information isn’t left out if these moments were to be cut entirely.

In the middle of this sequence from The Artist, a montage is used to quickly describe the rise of a new film star, who keeps getting bigger and better roles in an undetermined amount of time.

Invisible Cut

We end off on what seems to be an arbitrary term, although it is vital for numerous productions. The invisible cut is the cut that, well, is invisible. You’re not meant to know it is there. Proper shooting of the previous and following scenes is needed to create the illusion that no cut has taken place. With the rise of films meant to look like they are shot in one single take, invisible cuts are essential to keep this illusion alive.

The start of this scene from Birdman contains an invisible cut which is one of the more obvious examples of the film. The cut takes place when the subject is opening the bar door, and your vision is obstructed very briefly. To distract you from this cut, the subject is shot lingering before and after the cut, so you don’t focus too much on the split moment where a cut was snuck in.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.