Sound History in Film: Early Recording

Sound is considered half of the cinematic experience, but it wasn’t always that way. For the first few decades in film history, sound didn’t really exist. The original shorts were viewing experiments more than anything. Eventually, when film developed into a story telling art form and was presented to public crowds, music was added to accompany what was being shown on screen. Accompaniment is something that many movie buffs today may take for granted, unless they purposefully go and see a silent film with said accompaniment as a special presentation (these still happen, and I couldn’t recommend the experience enough; at least try it once). Of course, this clip isn’t from the ‘20s or before, but this much more recent recording of a piano accompaniment for a Buster Keaton short may give you an idea of what going to the cinemas in the silent era may have felt like.

So, as we all know, the first film with recorded sound is The Jazz Singer right? It’s often called the first film to do so, so it must be.

Wrong.

The Jazz Singer might be the most popular film to have recorded sound, but it is far from the first. Very far. Today’s lesson will showcase all of the technology that came before.

The Jazz Singer was released in 1927, and marked the major turning point when talking pictures (or “talkies” began to slowly overtake silent films). The very first film to have recorded sound, however, came out a little bit before The Jazz Singer.

How much earlier?

Try around 1894. The Dickson Experimental Sound Film was audibly recorded on a wax roll professionally called a phonograph cylinder, developed by Thomas Edison’s recording company. Here is that film below.

Okay, so it doesn’t sound great, but the experiment was a success of sorts. Chances are The Dickson Experimental Sound Film isn’t nearly as discussed about, because of the measures needed to repair the cylinder with the recording on it (and put back together the film as a whole). Perhaps the experiment was lost in time up to a certain point. In the film, you can see the violinist playing towards a massive recording cone called a Graphophone: an evolved version of the phonograph. It couldn’t pick up much sound, and the actual recording equipment itself (particularly the needle scraping on the cylinder) can be heard in the recording as well. So, clearly, this was a faulty system, despite the innovation.

To see this recording equipment in action today, YouTube musician Rob Scallon put together an experiment by trying to record modern day instruments with this one hundred year old technology.

Of course, the cylinder approach seemed impractical. You could only record up to two minutes of sound (which, in the 1890’s, wasn’t terrible, but it would become a problem later), and you had to play both the film and the cylinder at the same time. Of course, film wasn’t quite what it is now back then, and was still a bit of a gimmicky form of entertainment, rather than anything to be taken too seriously.

Nonetheless, advancements were still to take place. Fast forward many silent years, and skipping over many other sound experiments, and we reach Lee de Forest, the crowned “Father of Radio”, thanks to his innovations in sound projection and recording (including the first amp). A few years before The Jazz Singer, De Forest was trying to push for sound to be a part of film. After numerous experiments, he created the “phonofilm” alongside fellow inventor Theodore Case. Light was projected onto audio track photocells, so sound would be recorded at the same time as visuals were photographed, creating a marriage between sound and vision (without delays). You can see how this works (plus some of De Forest’s previous failed experiments) below.

To get an idea of what a phonofilm recording would sound like, here is an early example featuring jazz musicians Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake (thus making The Jazz Singer not even the first film with sound recording of jazz music).

To contrast that musical number, here’s a 1926 film (incorrectly labeled as 1923) featuring talking, still with phonofilm technology.

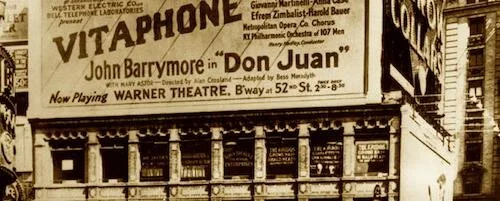

Phonofilm was a breakthrough, because it was the first notable combining of photograph and sound on the same film strip. However, big studios weren’t fully sold on this technology yet, particularly because of how much better physical recording was by the mid ‘20s (compared to the phonograph cylinders of decades prior). Now, the Vitaphone was making big ground, particularly because Warner Bros. studios were working with Western Electric on their latest inventions to coincide their technology with the releases of new films. Inspired by De Forest’s previous inventions — particularly his amplification practices — Western Electric’s Vitaphone seemed like the perfect launching point. They worked with records rather than cylinders, and each record could hold eleven minutes, which was around the length of film reels; each time a reel was changed, so was the record.

This was a big event. The announcements were made with Vitaphone technology, appropriately. Here is one of those notable announcements made by Will Hays, the then-chairman of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (also the man in charge of the “Hays Code”, which I will discuss another day in full).

So Hays was announcing the Vitaphone to the masses to hype up Don Juan’s premiere. Before we get to that film, it might be wise to look at what a Vitaphone disc sounds like. Here’s preservationist and historian extraordinaire Seth Winner playing around with such a disc, and explaining his remastering process (and the qualities of the disc while he’s recording).

Vitaphone discs couldn’t quite do much, but they were enough at the time. So, Don Juan was released as the flagship Vitaphone film. In the following clip, you’ll find that there isn’t any talking. That’s because Don Juan’s recordings were saved for music and sound effects, which at least helped with not needing to have musical accompaniment at every theatre showing of this film.

In a similar way, The First Auto focused much more on the sound effects that could be recorded, as to place listeners in the scenes that they are watching. You can hear a car horn beep, and race cars zip around the track in the following clip.

And now we have reached The Jazz Singer. So, let’s backtrack.

•The first film with recorded sound was The Dickson Experimental Sound Film released around 1894.

•Lee de Forest and Theodore Case invented phonofilm, and recordings of singing and talking that predate The Jazz Singer have been discovered.

•Don Juan was released — and heavily promoted — by a studio in 1926.

So, surely The Jazz Singer was the next Vitaphone release, right? Well, maybe after The First Auto? Right?

Something to remember before we continue: Vitaphone records were catalogued, and multiple were used for each film, just like multiple reels would be used.

So, maybe The Jazz Singer is something like the tenth-to-thirtieth Vitaphone records attached to films, considering it isn’t the first.

Try this. The Jazz Singer’s Vitaphone records are catalogued as the 2205th to the 2227th Vitaphone discs currently recorded, according to Roy Liebman in his book Vitaphone Films: A Catalogue of the Features and Shorts, which you can find and see for yourself here.

Alright, enough trashing of The Jazz Singer. Here’s what happened. Al Jolson was a recognizable name and the figurehead of this film that could sell tickets. The film was mostly silent, but Jolson’s musical numbers were recorded and presented to audiences. Not only that, but his chit-chat could be found too, which was definitely something audiences would want (imagine not knowing what the earliest celebrities sounded like, only to finally have your first answer). You can check out such moments below.

In short, The Jazz Singer was the first notable sound picture, because that’s what Warner Bros. wanted. Okay, so it was a feature film with both a recorded score and the talking and singing included as well. That’s still an important feat to the history of film. However, discrediting the many experiments and films of short and long (I didn’t even bother including them all here) is a disservice to the many years of film history that are just as important. Sure, The Jazz Singer was the turning point, because that’s when Warner Bros. made it the turning point. What if a studio took a gamble with the phonofilm years earlier, and heavily marketed the premiere of that film? Either way, I’m almost grateful for The Jazz Singer taking so much credit, because it’s exciting to discover just how much history preceded what is deemed the most historical moment in talking pictures; film history simply isn’t that simple.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.